Mount Tabor Indian Community

The Mount Tabor Indian Community (also Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands of the Mount Tabor Indian Community) is a state-recognized tribe made up of primarily Cherokee as well as Choctaw, Chickasaw and Muscogee-Creek people located in Rusk County, Texas. They are descended from Cherokee who had migrated to Texas prior to the Cherokee War of 1839 under Duwa'li, or The Bowl.[2] They were later joined by members of other remnant southeast tribes, such as the Yowani Choctaw, Chickasaw and Muscogee.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 600+ [1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Cherokee, Choctaw-Chickasaw Mount Tabor Dialect | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional Tribal Religion, Native American Church, Presbyterian, United Methodist, Southern Baptist, Nazarene | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek |

After the Cherokee War in 1839, the Cherokee sought refuge in Monclova, Mexico, to evade military action by the Republic of Texas, which was trying to expel Indians from East Texas. Led by Chicken Trotter, also known as Devereaux Jarrett Bell, the group fought a guerilla campaign against the Republic of Texas from Mexico throughout 1840 to 1842.

The Cherokee saw action in Corpus Christi, San Patricio and later followed General Adrián Woll in his occupation of San Antonio De Bexar. The Cherokee and allied Yowani, along with Mexican regulars, defeated the Dawson Expedition, but they were defeated in turn by Texas Army forces at the Battle of Salado Creek. With the signing of the Treaty of Birds Fort, hostilities ended between the Republic of Texas and the Texas Cherokee, who were granted formal recognition in Texas. These Cherokee were soon joined by other Cherokee from Indian Territory, from the Old Settler and Ridge Party groups. Due to internal political conflicts resulting from the forced removal from their eastern homeland, culminating in the Starr War, the Old Settler and Ridge Party sought a separation from the dominant Ross faction of the Cherokee Nation.

In 1844 United States President James K. Polk issued an Executive Order for these two bands to seek lands suitable to settle on in Texas.[3] Following the establishment of the community some six miles south of present-day Kilgore, Texas, the Cherokee were soon joined by Yowani Choctaw, intermarried Chickasaw and McIntosh Party Creek Indians. Today the band is made up of those descendants that continue to reside there. The band's current headquarters is in Kilgore, Texas, with significant populations near New London, Overton, Arp and Troup, Texas.

History

Descendants of the four American Indian tribes that make up the Mount Tabor Indian Community have a shared experience in the colonization of the American Southeast by Europeans. They suffered encroachment and Indian Removal through the 1830s. From different language families, the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Creek refugees came together in Texas, forming a community. It was initially dominated numerically by Cherokee Indians, however, since 1900 the majority of the band have been of ethnic Choctaw and Chickasaw ancestry.

The four tribes that combined as the Mount Tabor Indian Community since the late 19th century migrated in stages to east Texas. The first were survivors of the Cherokee War. With the violation of the Treaty of Bowles Village on February 23, 1836, between the Consultation of the Republic of Texas and the Texas Cherokee, the Texas Army ruthlessly pushed the Cherokee and allied Lenape (Delaware) and Shawnee Indians from the treaty lands, scattering them to multiple locations.[4]

A band of Cherokee sought refuge in Monclova, Coahuila, Mexico, led by Fox Fields and Chicken Trotter, who was also known as Devereaux Jarrett Bell. From there, along with their Mexican liaison, Vicente Córdova, the Texas Cherokee fought a guerrilla war against the Republic of Texas from 1840 until they ceased hostilities with the signing of the Treaty of Birds Fort.[5] A combined force of Texas Cherokee, Yowani and Mexican militia saw action against the Republic at San Patricio and Corpus Christi, with the final confrontations coming with General Adrián Woll's invasion of San Antonio de Bexar in September 1842. There, they were involved in the defeat of the Dawson Expedition but lost at the Battle of Salado Creek. Some eighteen Cherokee were killed along with Vicente Córdova, their Mexican military liaison. Shortly after this, with Sam Houston returning as President of the Republic of Texas, they sought peace, which was realized at Birds Fort.

During this same period, the larger Cherokee Nation had carried their internal rivalries after removal to their new lands in Indian Territory. The followers of Major Ridge, who had formed the Treaty or Ridge Party that signed the Treaty of New Echota, clashed with the new arrivals who came after the Trail of Tears and forced removal by the United States. The followers of Principal Chief John Ross had initially opposed removal, and carried out their capital sentence against persons who had ceded their lands, as they saw it. The Ridge Party had accepted the treaty and removal because they thought to do otherwise was to risk the destruction of the greater Cherokee Nation. A third Cherokee faction were the Old Settlers, who had earlier migrated to the west, first to Arkansas and then to Indian Territory, before the signing of the Treaty of New Echota. They had established a functioning government separate from their eastern kinsmen.

While the Old Settler and Ridge Party had cooperated, the arrival of the much larger Ross faction threw all of Indian Territory into chaos. After the Ross faction Cherokee assassinated Major Ridge and some of his allies, carrying out what they considered a capital sentence, the Old Settler and Ridge Party party factions sought relief. First, they proposed a division of the Cherokee Nation, with the southern part going to the Old Settlers and Ridge Party, and the north to the Ross supporters, forming two separate Cherokee governments. That idea was rejected by the federal government. But in 1844, United States President James K. Polk issued an Executive Order granting both Old Settler and Ridge Party factions permission to send a delegation to Texas to find land suitable for them to settle on.[6]

The Republic of Texas was still a separate nation and had its own ideas about desirable settlers. The arrival of the immigrant Cherokee led to a tense period.[7] It had been only five years since the Cherokee War and a little over a year since Chicken Trotter had signed a new treaty with Texas at Birds Fort.

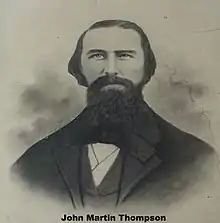

The Old Settler-Ridge Party delegation was led by John Harnage, James Starr, J.L. Thompson, and John Adair Bell. Also known as John "Jack" Bell, he was a brother of Chicken Trotter, and had been one of the signatories of the Treaty of New Echota. These two groups met near present-day Waco in mid-1844.[6] At that time, the Cherokee were prohibited from owning land in the Republic of Texas. To solve this problem, Benjamin Franklin Thompson, the European-American husband of Annie Martin, a Cherokee woman, purchased 10,000 acres (40 km2) of land for the band near what is now Kilgore, Texas. Her father John Martin served as the First Chief Justice of the Cherokee Nation.[8] With this purchase and a similar purchase to the south of the Thompson land by Jesse Mayfield, another European American married to a Cherokee woman, the Cherokee effectively occupied a new homeland. Mayfield's wife was Sarah Starr, the great granddaughter of Beloved Woman (also known as Nancy Ward).

By the summer of 1845 families began the trek to Texas and safety. Joined by Cherokee from Monclova, Mexico, the Mount Tabor Indian Community was founded. The original Mount Tabor village was located some six miles south of where present-day Kilgore developed in Rusk County, Texas. It appears to have been established on or near the former village of Chief Richard Fields, which had been led by his son Fox Fields at the time of the Cherokee War. Annie Martin-Thompson was the niece of Chief Fields.

Between 1845 and 1850, numerous Cherokee families settled in Mount Tabor and Bellview, a settlement they developed. By 1850 families of Yowani Choctaw and related Chickasaw, who had been living in southern Rusk County, came to seek refuge with the Cherokee.[9] A group of Muscogee (Creek) of the McIntosh Party also headed south from Indian Territory after being threatened by an anti-removal Creek leader named Tuskeenhaw.[10] The McIntosh Party were a Creek pro-removal group similar to the Cherokee Ridge Party.

The Choctaw were led by Jeremiah Jones, followed by Archibald Thompson. The Muscogee were led by William and Thomas Berryhill, whose families had been tied to Broken Arrow and Horse Path towns in the former Creek Nation in the Southeast.[11]

With the annexation of Texas into the United States of America, Indians were allowed to own lands in the state. John Adair Bell soon purchased land just south of the Benjamin F. Thompson lands. He wrote in a letter to his brother-in-law Stand Watie, "I call my place Mount Taber", listing his address as Mount Taber, Texas.[12] This was the first documented reference to the community.

As the community grew, it flourished.[13] That would change as the members became caught up in the American Civil War.

American Civil War

The entire band allied with the Confederate States, with most Cherokee serving with General Stand Watie, who had lived for short periods at Mount Tabor. His wife Sarah Caroline Bell-Watie lived there in 1863 with her sister Nancy Bell and brother-in-law George Harlan Starr.[14] While most of the Cherokee males of Mount Tabor served under Watie and former Mount Tabor resident Colonel William Penn Adair with the Second Cherokee Mounted Rifles, some chose to serve with other Texas units. John Martin Thompson organized units at Bellview, which were composed of Cherokee as well as Choctaw and intermarried whites. The band suffered greatly during the war. They suffered war-related shortages, and a number of Cherokee, mostly women and children related to members of Watie's command, fled to Rusk County for refuge deep in Texas. The band's limited resources were strained.

Following the war and the death of John Ross in 1866, the Cherokee Nation passed a "right of return" for members who wanted to rejoin the Nation. Between 1866 and 1890, more than 80% of the Cherokee left Mount Tabor to return to the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory. The Choctaw and Muscogee had different reactions after the war. Most of the Berryhill and related families were scattered throughout Texas and western Louisiana, with groups in Limestone and Angelina counties in Texas and Natchitoches Parish in Louisiana. Another sizable group headed north to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, putting down roots near what is known as Eufaula, Oklahoma. The Choctaw met with considerable resistance from authorities in Indian Territory.

Dawes Commission

Some Yowani Choctaw had left Texas shortly after their village on Attoyac Bayou was attacked and eleven members massacred by white vigilantes from Nacogdoches in 1840. They settled in the southern Chickasaw Nation not far from Ardmore, Oklahoma near Houani Creek. Around 1885 William Clyde Thompson, along with John Thurston Thompson Jr., Winburn Jones and Martin Luther Thompson, led Choctaw from Rusk and neighboring Smith County, Texas to the Ardmore area in the Chickasaw Nation. They wanted to register as members in the Choctaw Nation during enrollment on the Dawes Rolls.[15]

While all the Texas Choctaw relocating to Indian Territory were initially enrolled on the Final Roll of the Choctaw Nation, they were later stricken. Initially listed as Mississippi Choctaw, they were later changed to MCR (Mississippi Choctaw Rejected). Tribal officials said they no longer belonged, as they and the related Jena Choctaw in Louisiana, had not been in Mississippi for multiple generations. But their ancestors had been parties to previous Choctaw treaties with the US while still residing in Mississippi. The Department of the Interior acknowledged the Choctaw ancestry but the Choctaw Advisory Board wanted to admit only those relocating from Mississippi. The Jena Band of Choctaw Indians in Louisiana faced the same rejection. It was not until 1995 that the Jena Choctaw were finally federally recognized as a distinct tribe.[16]

Martin Luther Thompson and others returned to Rusk County, living there for the remainder of their lives. Those who had stayed with William Clyde Thompson and settled near the town of Marlow, fought the issue all the way to the United States Supreme Court. The court sided with these Choctaw, and they were entered on a reinstatement list, restoring their Choctaw citizenship. Some 70 Texas Choctaw from Mount Tabor were recognized as "Choctaw by Blood" and citizens of that nation.[17] But unlike the Cherokee, most Choctaw and Chickasaw of Mount Tabor remained in the east Texas tribal community.

During this same period, Caleb Starr Bean, who served as the Mount Tabor community Chief, sought to gain enrollment on the Dawes Roll for the remaining Mount Tabor people. He was unsuccessful as the enrollment was based on physical residence in the Cherokee Nation.

Enrollment on the Guion Miller Roll, which was a payment roll based upon previous treaties, was open to all Cherokee listed on the 1835 Cherokee census taken at the time of Indian Removal. Those who were or had ancestors among the original Texas Cherokee, as well as the Choctaw and Muscogee, were not eligible. Those who did not remove to Texas until after the Cherokee arrived in Indian Territory in 1839, were eligible. Chief Caleb Bean worked diligently to insure that all known Mount Tabor Cherokee people who were eligible, had a chance to apply for Guion Miller enrollment.

He died in 1902 before the roll was closed, but his brother John Ellis Bean became the next community Chief and took over his efforts. Chief John Bean kept the tribal organization together under what were increasingly hard times. The land was not known for producing well. The forests had been largely harvested by lumber companies owned by the Thompsons. The Thompson and Tucker Lumber Company, owned by John Martin Thompson, dominated in the region.[18]

Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands

Shortly after the Civil War, former Mount Tabor resident William Penn Adair, reorganized the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands. This organization, which was started in Mount Tabor in the 1850s, was established to pursue redress from the violations of the Treaty of Bowles Village in 1836. The State of Texas initially offered some fifteen million acres of Texas Panhandle land, on the condition that the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands drop any further legal action related to the treaty. Adair refused.

The lands now occupied by the Texas Cherokees had become a new homeland. Many of the community's ancestors were buried there, and the people were doing relatively well in East Texas. Whey they assessed the lands offered, they took into account that these 15 million acres were occupied by the Comanche and Kiowa peoples. They would have reacted to Tabor or other Cherokee as intruders. War would have been inevitable. Adair thought this was unacceptable. Before the Texas revolution, the Mexican government had offered similar land, in order for the Texas Cherokee to move west and form a barrier to the Comanche, Lipan Apache, and other tribes. That had been rejected by The Bowl and Adair followed suit.

Following the war, with a Confederate Cherokee delegation in Washington, William Adair tried to gain approval for Confederate Cherokees to be allowed to return to the treaty lands in east Texas. It was unsuccessful. Following the death of Stand Watie in 1871, Adair reorganized the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands (TCAB). He would lead the organization assisted by Clement Neely Vann. At this point, Mount Tabor was deeply involved in the organization.

Adair, who needed more money than that supplied by John Martin Thompson, reached out to the Fields family for financial support for continued legal action. From 1871 to 1963, the TCAB filed suits in an effort to gain more compensation for treaty violations. The first were filed against the State of Texas from 1871–1875, after which the state later changed its constitution to block further attempts. The TCAB sought land through filing liens in Rusk and Smith counties in 1914, and reached the United States Supreme Court on appeal in 1920–21, and the Indian Claims Commission in 1949–1953. The suit of 1963 was led chiefly by the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and did not include the Mount Tabor Indian Community.[19]

Following the deaths of William Adair and Clement Vann, John Martin Thompson took over the Chairmanship of the Executive Committee of Mount Tabor. He remained in that position until his death 1907. John Ellis Bean then served both as the local community Chief and TCAB Executive Committee Chairman. In 1915, at a meeting of the General Assembly held in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, with nearly 500 Texas Cherokee present, Jake Claude Muskrat was elected the next TCAB Executive Committee Chairman. He was the first TCAB Chairman who had not lived at Mount Tabor. Muskrat, a descendant of Chief Richard Fields, was succeeded in 1939 by William Wayne Keeler, known as W.W. Keeler. U.S. President Harry Truman appointed Keeler as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation in 1949. He served in both capacities with the Cherokee Nation and TCAB until 1972, when the Cherokee Nation established a constitution for electoral government.

After the death of Thompson, the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands became more influenced by the majority of Cherokee in Oklahoma. During the 1920 effort to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, a major schism developed between TCAB attorney George Fields and Texas leader Martin Luther Thompson. Fields contended that this was a Cherokee Nation effort.[20] Fields wanted the Choctaw to be excluded from the Cherokee Nation. He struck the word "Choctaw" out of his papers related to the case.[21] He left the word Jawanie (Yowani), included in the original treaty, but Martin Thompson's believed that not all Mount Tabor Choctaw (including his wife) were Yowani. Fields tried to push out the Mount Tabor descendants, but stopped short due to pressures by Claude Muskrat and John Ellis Bean.

Texas Oil Boom

In Texas, the community maintained its local leadership. Following the death of John Ellis Bean in 1927, J. Malcolm Crim took over as leader, with Martin Luther Thompson as his second. The Great Depression hit the area hard, but was dramatically relieved by the discovery of oil on October 3, 1930 by Columbus M. "Dad" Joiner, at Daisy Bradford #3 near Kilgore, and soon thereafter at Lou Della Crim #1. This was followed by many more in areas occupied by the Tabor people. Lou Della Thompson-Crim was the daughter of John Martin Thompson. This discovery changed her life and many others forever. The 1930 oil boom was a two-edged sword for the Mount Tabor Community. It lifted up many of the band out of poverty, but the newfound wealth destroyed traditional indigenous culture, transforming it overnight.

As a businessman, Malcolm Crim did well for the community, ensuring that many descendants from Kilgore to Troup were not taken advantage of by the abundance of less than scrupulous individuals who flooded into tribal areas. Over a four-week period Kilgore went from a sleepy town of 500, with a sizable Native population, to a city of 10,000, made up of rough migrants and speculators. Change was inevitable even with Malcolm Crim as the first mayor of Kilgore.

By 1933, Crim was focused on his own business interests. Foster Trammell Bean became the next community Chief. Foster Bean was the grandson of Chief John Ellis Bean. He served as a local attorney, judge, and as mayor of Kilgore for twenty years. He maintained a good relationship with W.W. Keeler, but served only intermittently on the TCAB Executive Committee. With the death of Martin Luther Thompson in 1946, all local leadership was concentrated under Judge Bean.

1972 to present

In 1972, as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma was reorganizing and preparing to elect its first Principal Chief since statehood, it was becoming more politically distant from the Mount Tabor Community. Keeler had been reappointed Principal Chief by every U.S. President from Truman to Nixon. In anticipation of more changes and with Native American activism focused on local control, he resigned as Chairman of the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands. Foster Bean assumed all responsibilities, making the TCAB again reflect only a local Texas organization. With the approval of the 1975 Cherokee Nation constitution, the TCAB ceased to exist in Oklahoma without a vote. Since, it has been active only in Texas. Some Oklahoma Cherokee have continued to serve on the Executive Committee, such as Mack Starr and George Bell, but after 1980 all Executive Committee members have been tied to Mount Tabor in Texas only.

Judge Foster Bean served as Chairman of the Executive Committee of the TCAB until 1988. J.C. Thompson was appointed by the Committee to replace him.[22] Bean remained a member of the Executive Committee, which included Billy Bob Crim, R. Nicholas Hearne, and Saunders Gregg.

Thompson first addressed the community's standing as a recognized tribe. Secondly, he suggested changes to the name of the organization. The organization no longer used "Mount Tabor" and was known as the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands. Since the Executive Committee saw that the TCAB as the dual state organization, which after 1975 only remained viable in Texas. The committee proposed the name" Texas Band of Cherokee, Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians". That, and the proposed "Texas Band of Cherokee Indians" were both rejected by the General Assembly, made up of all adult members.

The Choctaw descendants were offended by the latter proposal, they felt slighted, even though many are both Choctaw and Cherokee. The compromise in 1992 was to return to the band's original name, plus retaining the TCAB title. Since then the official name has been the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands of the Mount Tabor Indian Community. With the explosion of fraudulent groups claiming to be "Cherokee Tribes", the Executive Committee in 1998 no longer referred to the community by the TCAB title, but as Mount Tabor. The Executive Committee and General Assembly do not consider the community to be either "Cherokee" tribe, Choctaw, Chickasaw, nor Muscogee, but rather a combination of peoples who have are an interrelated band by blood, marriage and history.

J.C. Thompson served as Chairman until 1998, when Terry Jean Easterly was selected as the first woman to lead the community. Easterly is also the first leader who has not had Cherokee ancestry. She is Choctaw, Chickasaw and Creek, a descendant of both the Thompson-McCoy and Jones families through Arthur Thompson, brother of William C. Thompson. She served from 1998 to 2000 and was succeeded by Peggy Dean-Atwood, a descendant of Archibald Thompson, who also had no Cherokee ancestry. Atwood served through 2001. After her resignation, J.C. Thompson became Chairman for the second time. He served until August 2018, when he was succeeded by William Ellis "Billy" Bean, the great-grandson of Chief John Ellis Bean. Chairman Bean was suspended by the Mount Tabor Tribal Court from office after having served 13 months on September 2, 2019.[23] He was succeeded by Cheryl Aleane Giordano, the third woman to hold the position. Ms. Giordano is a descendant of the Thompson-McCoy family and is of Choctaw and Chickasaw descent. She had previously served as Operations Coordinator on the Mount Tabor Executive Committee.

Mount Tabor Indian Community

In 1978 the band set up its first by-laws that were distinct from the 1925 Texas Cherokee and Associate Band by-laws. In 1998, the band approved a new constitution. In 2017 they approved another constitution, part of their effort to meet federal standards for self-government and to gain federal recognition as a tribe by the Secretary of Interior. in their Federal Acknowledgment Project.

The band started seeking federal recognition in 1990 but the project was tabled in 1992, in part due to a misunderstanding of the criteria established by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (in consultation with tribes). The band revived its current Federal project in 2015. The Mount Tabor Indian Community in 2017 was one of five tribes recognized by the State of Texas.[24] Three of the other Texas tribes: the Alabama-Coushatta, The Tigua of Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, and the Traditional Kickapoo, have gained federal recognition. The Lipan Apache Tribe of Texas, like Mount Tabor, is recognized only by the state.

In the early 21st century, the band holds an annual reunion usually in either Kilgore or Troup. It maintains strong connections to three of their traditional cemeteries, the Asbury Indian Cemetery near Overton, the Thompson Cemetery at Laird Hill, and the Mount Tabor Indian Cemetery in rural Rusk County. Additionally, the band publishes a quarterly newspaper, The Mount Tabor Phoenix, for its nearly 600 citizens.

Religion

While certain ceremonies including stomp dances are continued, the people gradually absorbed Christianity, practicing primarily Protestant forms. As the Tabor people settled in this area between 1845 and 1850, their beliefs initially reflected tribal identities. The religions adopted by tribes related to their near European-American neighbors and activities of missionaries. To the north (Kilgore area) the Cherokee followed the Presbyterian faith, while in the south (New London to Troup), the predominant faith among the community was Methodist.

In the late 19th century and well into the twentieth, the community was influenced by Reverend Evan Fletcher Thompson (Choctaw-Chickasaw), who left the Methodist Church for the Nazarene faith. Many churches throughout southern Smith and northwestern Rusk counties were started by Reverend Thompson.

Today's band is a diverse group religiously. Some members have tried to revive elements of the historic faiths of the southeastern peoples, and a few are involved with the Native American Church. The majority are affiliated with mainline Protestant faiths. The Southern Baptists and Church of Christ have attracted members, making inroads within more traditional families. The Crim family of Mount Tabor donated the funds for the First Presbyterian Church's Opus 1173 pipe organ. The music from this organ continues to be heard in services today. The First Presbyterian Church in Kilgore is historically the one most tied to Mount Tabor people.

Tribal government

1845–1871: The Tribal Government of the Mount Tabor Indian Community had a Community Chief, with the citizenry making up a General Assembly.

1871–1907: The community maintained a Community Chief, but other larger activities were dealt with by a Chief and later Chairman of an Executive Committee made up by both descendants in Texas and Oklahoma. Local decisions were still dealt with locally by a General Assembly.

1907–1945: The Community Chief dealt with most issues but the General Assembly was split between Kilgore, Texas, Tahlequah, Oklahoma and later Bartlesville, Oklahoma. In the 1915 General Assembly meeting in Tahlequah, Oklahoma with nearly 500 in attendance, Jake Claude Muskrat was elected the first TCAB Chairman that did not nor had not lived at Mount Tabor. He was a direct descendant of Texas Cherokee Chief Richard Fields. The 1925 General Assembly, one of the largest on record, had an attendance of well over 500 and was held in Miami, Oklahoma. The Chairman of the Executive Committee was the Chief Operating Officer.

1945–1972: The General Assembly was split, but the Thompson Reunion Committee led by Otha Bradford (Brad) Thompson and his brother, Templeton Altman (Temp) Thompson established and controlled the annual meetings through 2001. TCAB activities were almost exclusively handled out of Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Local business issues were still dealt with through Foster Bean.

1972–1998: The government returned to a more traditional form with all activity out of Kilgore, Texas and a general Assembly meeting annually.

1998–2017: A constitution ratified in 1998 established a three-tiered government, enlarging the Executive Committee from five members, which it had been since 1871 and making it a seven-member body. The General Assembly remained the same and a new branch was added, a Tribal Court, with Judge Saunders Gregg being the initial Chief Justice.

2017–Present: With a new constitution adopted in August 2017, the Mount Tabor Indian Community reduced the Executive Committee to a five-member body, consisting of the Tribal Chairman; Deputy Chairman, Secretary, Treasurer and Operations Coordinator. The Tribal Court remained a three-member body. The biggest change that the General Assembly voted on in 2016, was making it easier for speedy decisions related to the Federal Acknowledgment Project and designing a system that would be acceptable to the Secretary of the Interior with hopefully few changes. The General Assembly was phased out and a new seven-member Tribal Council would be set in place by June 1, 2018. The Tribal Council is divided into five districts consisting of; (1) Kilgore District; (2) Overton-Arp District; (3) Sand Hill District; (4) Screech Owl Bend District; and (5) New London District. There are also two At-Large Districts; (6) At-Large District One; representing members living outside of the tri-county area (Gregg, Rusk and Smith) but still in the State of Texas and finally (7) At-Large District Two, comprising all enrolled members living outside of the State of Texas.

Citizenship

Mount Tabor citizenship (membership) is limited to lineal descendants of six extended families, represented by specific progenitors whose family remained within or in contact with the Mount Tabor Indian Community from 1850 to the present. The six primary progenitors are: 1. Annie Martin-Thompson, a Cherokee Indian and her husband Benjamin Franklin Thompson; 2. John Ellis Bean and his wife Henrietta Cloud Dannenberg-Bean, both Cherokee Indians; 3. Nannie Sabina Harnage-Bacon a Cherokee Indian and her husband John Dana Bacon; 4. Margaret McCoy-Thompson, a Choctaw & Chickasaw Indian and her husband Henry Thompson through their sons: 4.a Henry Thompson Jr and his wife Percilla Jackson-Thompson, a Choctaw Indian (only his descendants that settled in Rusk, Smith or Gregg counties) 4.b Archibald Thompson and his wives Elizabeth Jackson-Thompson, a Choctaw Indian; Nancy Islea, ancestry unknown; Anna Strong Thompson, non-Indian (only his descendants that settled in Rusk, Smith or Gregg counties) 4.c William Thompson and his wife Elizabeth Jones Mangum-Thompson, a Choctaw Indian (all of his descendants, including those that relocated to Trinity and Angelina counties as long as they can document continued contact with the community); 5. Samuel Jones aka Nashoba, a Choctaw Indian (only his descendants that settled in Rusk, Smith, Gregg counties); 6. Martha Elizabeth Derrisaw-Berryhill (Durouzeaux), a Muscogee-Creek Indian and her husband John Berryhill, a Catawba Indian, (only his descendants that settled in Rusk, Smith, Gregg counties).

Other families may qualify based upon lineal descent from an ancestor(s) who were part of the historical community but are now members of the Cherokee Nation; Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma; Chickasaw Nation; Jena Band of Choctaw Indians or Muscogee-Creek Nation. These families are limited to parts of the Adair, Bell, Buffington, Fish and Starr Cherokee families.

The Mount Tabor Indian Community is a lineal descendant band that does not have a minimum tribal blood quantum for citizenship.

Mount Tabor chiefs and leaders

Mount Tabor Community Chiefs.

1840–1845: Chief Devereaux Jarrett Bell aka Chicken Trotter

1840–1860: Chief John Adair "Jack" Bell

1860–1861: Chief George Harlan Starr

1861–1881: Major John Martin Thompson

1881–1902: Chief Caleb Starr Bean

1902–1927: Chief John Ellis Bean

1927–1933: John Malcolm Crim

1933–1988: Judge Foster Trammell Bean

1988–1998: Chairman J.C. Thompson

1998–2000: Chairperson Terry Jean Easterly

2000–2001: Chairperson Peggy Dean-Atwood

2001–2018: Chairman J.C. Thompson

2018–2018: Chairman Billy Bean

2019–Present: Chairperson Cheryl Giordano

Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands Executive Committee Chairmans other than Mount Tabor Community Chiefs.

1871–1880: Chief William Penn Adair (Also served as Assistant Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation)

1874–1907: Chairman John Martin Thompson (Served as Community Chief and Executive Committee Chairman)

1907–1915: Chief John Ellis Bean (Served as Community Chief and Executive Committee Chairman)

1915–1939: Chairman Jake Claude Muskrat

1939–1972: Chairman William Wayne Keeler (Also served as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation)

1972–1988: Judge Foster Trammell Bean (Served as Community Chief and Executive Committee Chairman)

1988–1998: Chairman J.C. Thompson (Served as Community Chief and Executive Committee Chairman)

1998–2000: Chairperson Terry Jean Easterly (Served as Community Chief and Executive Committee Chairman)

2000–2001: Chairperson Peggy Dean-Atwood (Served as Community Chief and Executive Committee Chairman)

2001–2018: Chairman J.C. Thompson (Served as Community Chief and Executive Committee Chairman)

2018–2019: Chairman William Ellis "Billy" Bean (Serves as Community Chief and Executive Committee Chairman)

2019–Present: Chairperson Cheryl Aleane Giordano (Serves as Community Chief and Executive Committee Chairperson)

Texas Choctaw-Chickasaw Leaders

1847–1851: Jeremiah Jones

1851–1856: Archibald Thompson

1856–1864: Lieutenant John Thurston Thompson Sr. (killed in the Battle of Jenkins Ferry, Saline County, Arkansas during the American Civil War)

1881–1946: Martin Luther Thompson

1890–1912: Captain William Clyde Thompson (elected Texas Choctaw Leader for those in the Chickasaw Nation)

Muscogee-Creek Leaders

1847–1865: William Berryhill and his brother Thomas Berryhill

Other notable Mount Tabor Indians

Texas Cherokee; Mount Tabor related treaties and Texas State recognition

- Treaty of San Antonio de Bexar, with the Spanish Empire, November 8, 1822

Granted lands in the province of Tejas and Coahuila in Spanish Mexico for permanent settlement of the Texas Cherokee Nation, represented by Chief Richard Fields. Although signed by the Spanish governor of Tejas, the treaty was never ratified, neither by the Vice-royalty of New Spain nor by any succeeding government through the Texas Revolution.[25]

- Treaty with the Republic of Fredonia, December 21, 1826

Treaty with the short-lived Fredonia Republic. The rebellion led to the death of Chief Richard Fields.[26]

- Treaty of Bowles Village with the Republic of Texas, February 23, 1836

This treaty granted nearly 1,600,000 acres (6,500 km2) of east Texas land to the Texas Cherokees and twelve associated tribes, including the Yowani (Jawanie). It was the violation of this treaty that led directly to the Cherokee War of 1839. The treaty included all of Cherokee and Smith counties, the northwestern part of Rusk, northeastern Van Zandt and southern Gregg (formed from Rusk County in 1873) counties.[27]

- Treaty of Bird's Fort with the Republic of Texas, September 29, 1843

Ending hostilities among several Texas tribes, including the Texas Cherokees as negotiated by Chicken Trotter also known as Devereaux Jarrett Bell. This treaty which was ratified by the Congress of the Republic of Texas, recognized the tribal status of the Texas Indians as distinct, including the Cherokees that would later become known as the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands-Mount Tabor Tabor Indian Community. This treaty, honored by the State of Texas following annexation, has never been abrogated by the Congress of the United States and in theory is still valid.[5]

- Treaty of Tehuacana Creek with the Republic of Texas, October 9, 1844

An additional treaty was made in which Chicken Trotter "Devereaux Jarrett Bell" and Wagon Bowles were involved, the latter being the son of Texas Cherokee Chief Bowles also known as Duwa'li or the Bowl. This treaty was approved by the Texas Senate only. Chicken Trotter and his brother John Adair Bell (the latter a signer of the Treaty of New Echota) were part of the founding families of the Mount Tabor Indian Community in Rusk County, Texas.[28]

- Second Treaty of Tehuacana Creek with the Republic of Texas, August 27 to September 25, 1845

The Council of Tehuacana Creek was the last official contact between the Republic of Texas and many of its tribes. This treaty was never ratified as Texas was soon to be annexed into the United States of America. In this treaty Wagon Bowles is acknowledged as Chief of the Cherokees, whereas Chicken Trotter is titled Captain. It is unclear if any of the Old Settler or Ridge Party Cherokees participated, although based upon the dates of the council it is a good possibility.[29]

- Texas State Recognition of the Mount Tabor Indian Community, May 10, 2017,

84 SCR 25, a bill for recognition by the State of Texas of the Mount Tabor Indian Community [24][30]

References

- Handbook of Texas Online, uploaded 7 February 2018.

- Duwal'li TSHA online;

- Foreman, Grant (1934). The Five Civilized Tribes: A History of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole. pp. 336, 337.

- Clarke, Mary Whatley (1971). Chief Bowles and the Texas Cherokees, Chapter IX: The Cherokee War. pp. 94–111.

- Republic of Texas Treaties; Treaty of Birds Fort September 29, 1843, Texas State Historical Society, Austin, Texas

- Foreman, Grant (1934). The Five Civilized Tribes: Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole. pp. 336, 337.

- Winfrey, Day (1995). Texas Indian Papers: Volume II, 1844-1845: Texas State Historical Association, Austin, Texas. pp. 385–388.

- "Land Registration Deed, Benjamin Franklin Thompson: Rusk County County Clerks Office, Court House, Henderson, Texas". 1844. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Winfrey, Day (1939). Texas Indian Papers, Volume I. p. 23.

- "Letter of John Berryhill Microfilm Copy NAR NO 234, ROLL 236, Letters rec'd by the Office of Indian Affairs, Creek Agency 1826-1830 Frame 0072,0073,0074,0075". May 1, 1828. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dunn, Mary Franklin (1981). Rusk County, Texas 1850, United States Census. pp. 12, 23, 134.

- Dale, Edward (1995). Cherokee Cavaliers. pp. 80, 81.

- Dale, Edward (1939). Cherokee Cavaliers. pp. 79.

- Dale, Edward (1939). Cherokee Cavaliers. pp. 124-126.

- United States Department of the Interior, Secretary of the Interior-Choctaw Citizenship Cases, #4 William C. Thompson et al., pp. 151–157

- Letter of April 4, 1905 from Thomas Ryan, First Assistant Secretary Indian Affairs to Commissioner to the Five Civilized Tribes, Muskogee, Indian Territory, re: William C. Thompson et al. MCR 341, MCR 7124, MCR 581 and MCR 458

- Oklahoma Historical Society, Records of the Department of the Interior, Laws, Decisions and Regulations Affecting the work of the Commissioner to the Five Civilized Tribes 1893-1906, pp. 130–138

- American Lumberman Biographies (1908) http://www.ttarchive.com/library/Biographies/Thompson-JM_AL.html

- Clarke, Mary Whatley (1971). Chief Bowls and the Texas Cherokees, Chapter XI: Cherokee Claims to Texas Land. pp. 121–125.

- Fields, George W. (1921). Texas Cherokees 1820-1839: A document for litigation.

- Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Papers of George W. Fields 1920-1921

- Minutes to meeting TCAB- September 10, 1988, Kilgore Country Club, Kilgore, Gregg County, Texas,

- Tribal Court Case No. SC-2019-07-01, Mount Tabor Indian Community et al vs William Ellis Bean et al, Rusk County Clerks Office, Henderson, Texas

- http://www.legis.state.tx.us/BillLookup/Actions.aspx?LegSess=85R&Bill=SCR25

- Starr, Dr. Emmett (1971). History of the Cherokee Indians. pp. 194–195.

- Clarke, Mary Whatley (1971). Chief Bowles and the Texas Cherokees: Chapter IV, the Fredonian Rebellion. pp. 41–43.

- Republic of Texas Treaties; Treaty of Bowles Village February 23, 1836, Texas State Historical Society, Austin, Texas

- Republic of Texas Treaties; Treaty of Tehuacana Creek October 9, 1844, Texas State Historical Society, Austin, Texas

- Republic of Texas Treaties; Council of Tehuacana Creek September 25, 1845, Texas State Historical Society, Austin, Texas

- http://www.legis.state.tx.us/tlodocs/85R/billtext/html/SC00025F.htm

External links

- Book Search, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico By Frederick Webb Hodge

- A History of the Caddo Indians By: WILLIAM B. GLOVER

- Thompson Cemetery, Rusk County, Texas; Information related to Cherokee descendants buried there, by Paul Ridenour, 2005

- Mount Tabor Indian Cemetery, Rusk County, Texas

- Mount Tabor Indian Cemetery, Rusk County, Texas

- Asbury Indian Cemetery, Smith County, Texas, Information related to Choctaw and Cherokee descendants buried there, by Paul Ridenour, 2005

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Yowani Indians, Margery H. Krieger

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Indians by George Klos

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Mount Tabor Indian Community by Patrick Pynes

- Mt. Tabor Cemetery, Rusk County TxGenWeb

- A Starr Studded Event, April 9, 2005 by Paul Ridenour

- The George Harlan Starr and Nancy (Bell) Starr Home, Located near Leveretts Chapel, Texas (Mt. Tabor Indian Community), by Paul Ridenour 2005

- Ridenour's Major Ridge Home Page, by Paul Ridenour 2008