Citadel of Saigon

The Citadel of Saigon (Vietnamese: Thành Sài Gòn [tʰâːn ʂâj ɣɔ̂n]) also known as the Citadel of Gia Định (Vietnamese: Thành Gia Định [tʰâːn ʒaː dîˀn]) was a late 18th-century fortress that stood in Saigon (also known in the 19th century as Gia Định, now Ho Chi Minh City), Vietnam from its construction in 1790 until its destruction in February 1859. The citadel was only used once prior to its destruction, when it was captured by Lê Văn Khôi in 1833 and used in a revolt against Emperor Minh Mạng. It was destroyed in a French naval bombardment as part of the colonization of southern Vietnam which became the French colony of Cochinchina.

| Citadel of Saigon | |

|---|---|

| Saigon, Vietnam | |

Relic of the old Citadel of Gia Định | |

| Type | Square Vauban |

| Height | 20 m (66 ft) |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Nguyễn dynasty |

| Condition | Destroyed by French Navy in 1859 siege |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1790 |

| Built by | Nguyễn Phúc Ánh |

| In use | 1790–1859 |

| Materials | Granite, brick, earth (1835 version) |

| Demolished | 1859 |

| Battles/wars | Lê Văn Khôi revolt, Cochinchina Campaign |

In the late 18th century, the city of Saigon was the subject of warfare between the Tây Sơn dynasty, which had toppled the Nguyễn lords who ruled southern Vietnam, and Nguyễn Ánh, the nephew of the last Nguyễn lord. The city changed hands multiple times before Nguyễn Ánh captured the city in 1789. Under the directions of French officers recruited for him, a Vauban style "octagonal" citadel was built in 1790. Thereafter, the Tây Sơn never attacked southern Vietnam again, and the military protection allowed Nguyễn Ánh to get a foothold in the region. He used this to build an administration and strengthen his forces for a campaign that united Vietnam in 1802, resulting in his coronation as Gia Long.

In 1833, his son Minh Mạng was faced with a rebellion led by Lê Văn Khôi, which started after the tomb of Khôi's father Lê Văn Duyệt was desecrated by imperial officials. The rebels took control of the citadel and the revolt continued until the imperial forces took control of the citadel in 1835. Following the capture of the citadel, Minh Mạng ordered its razing and replacement with a smaller square stone-built structure, that was more vulnerable to attacks. On February 17, 1859, the citadel was captured during the French invasion after less than a day of battle and significant amounts of military supplies were seized. Realising that they did not have the capacity to hold the fort against Vietnamese attempts to recapture it, the French razed it with explosives, before withdrawing their troops.

Background

Central Vietnam was ruled by the Nguyễn lords, who had broken away in the early 17th century from the Trịnh lords, who ruled the north. The Nguyễn continued the southward expansion that eventually reaching the Mekong Delta. The southern edge of Vietnam, being further away from the Nguyễn power base in the centre, was loosely governed.[1]

In 1771, the Tây Sơn rebellion erupted from Bình Định Province.[2] In 1777, the last of the Nguyễn lords was deposed and killed.[3] His nephew Nguyễn Phúc Ánh was the most senior member of the Nguyễn family to have survived the Tây Sơn victory and conquest of Saigon in 1777.[4][5][6] Nguyễn Ánh fled to Hà Tiên in the far south of the country, where he met Pigneau de Behaine,[2][7][8] a French priest who became his adviser and played a large part in his rise to power.[8] Over the next few decades, there were continuous attacks and counterattacks by both sides and Saigon changed hands frequently.[2][9][10] Eventually, Nguyễn Ánh was forced into exile at Bangkok.[2] The Tây Sơn regularly raided the rice growing areas of the south during the harvesting season, confiscating the Nguyễns' supply of food.[2]

In 1788, the Tây Sơn moved north to attack the Trịnh and unite Vietnam. Nguyễn Ánh took advantage of the situation to return to southern Vietnam.[5][11] After rebuilding his army, he recaptured Saigon on September 7, 1788.[11] His grip on the south was enhanced by a group of Frenchmen and equipment that Pigneau had recruited, although the magnitude of the aid has been the source of dispute.[5][6][11][12][13][14][15][16]

Having seen Saigon slip from his hands on many occasions in the previous decade,[2] Nguyễn Ánh was keen to strengthen his hold on the key southern city, turning it into his capital,[17] and the base for his preparations for his planned conquest of the Tây Sơn and Vietnam. His enemies had regularly raided the area and confiscated the rice harvest.[17]

Construction

The French officers recruited by Pigneau were used to train Nguyễn Ánh's armed forces and introduce their technological expertise to the war effort.[11] Olivier de Puymanel was responsible for the construction of fortifications.[11][14][18] One of Nguyễn Ánh's first actions was to ask the French officers to design and oversee the construction of a modern European-style citadel in Saigon. The citadel was designed by Theodore Lebrun and de Puymanel and 30,000 people were used to construct it in 1790.[17] The townfolk and their mandarins were heavily taxed for the work, and the labourers were worked to the extent that it provoked a revolt.[17]

First structure

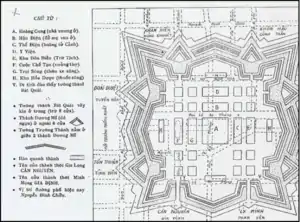

The stone and earth citadel eventually had a perimeter measuring 4,176 m (13,701 ft) in a Vauban model.[17] It was described as being of a Chinese style, designed in the octagonal form of a lotus flower, with eight gates[17] in the Đại Nam nhất thống chí, the official records of the Nguyễn dynasty.[19] However, such records are believed to have been written metaphorically, rather than literally. Two French maps of the city, drawn by de Puymanel and Jean-Marie Dayot—another senior officer[11]—in 1799 and 1815 respectively, show a square-shaped design, with four main towers at the corners, and six outer half-towers, centered at 10°46′58″N 106°41′53″E. Louis Malleret said that "it is impossible to see any octagonal design in this".[19]

The design suggested by the French maps is corroborated by the accounts of British and American visitors who travelled to Saigon seeking trade deals for their respective countries in the 1820s. British trade envoy John Crawfurd wrote that "the citadel of Saigon...is, in form, a parallelogram...I conjecture, from appearance, that the longest side of the square may be about three-quarters of a mile in length".[19][20] George Finlayson, a naturalist and surgeon who travelled to southern Vietnam as a member of a trade delegation from the British East India Company, described the fortress as being "of square form, and each side is about half a mile in extent".[19] Lieutenant John White of the United States Navy, travelling as a trade envoy for the United States, claimed to have seen only four of the eight gates, but Crawfurd wrote that "With the exception of the four principal gateways...the gates consist of four large and as many small ones".[19] The four small gates observed by Crawfurd are in accord with the design principles of Vauban.[19]

The two French maps of the citadel show a Vauban structure, as do the accounts of the trade delegates. According to Crawfurd, "the original plan appears to have been European, but left incomplete. It has a regular glacis, an esplanade, a dry ditch of considerable breadth, and regular ramparts and bastion...The interior is neatly laid out and clean, and presents an appearance of European order and arrangement."[20][21] Finlayson described the citadel as having been "constructed of late years, on the principles of European fortification. It is furnished with a regular glacis, wet ditch, and a high rampart, and commands the surrounding country."[21] Lebrun and de Puymanel did not choose the site for the citadel, instead using the compound of a fort. The location was seen as ideal for such a purpose. It was of substantial elevation, with three sides bordered by natural waterways at right angles: the Saigon River, Arroyo Chinois and the Arroyo de l'Avalanche.[21] Crawfurd reported that the walls were made of earth that was "covered everywhere with a green sward".[22] White estimated that the height of walls was around 6 m (20 ft).[23] According to Crawfurd, the gateways were built from stone and lime, with the towers being of Chinese architecture with a double-canopied appearance.[22] The approach towards the gates include a zig-zag in the glacis.[22]

The location was in complete fulfilment of the requirements of geomancy, with a north-west/south-east orientation. The three courses of water provided the "vital energy".[21] As three waterways formed right angles, the square structure was the most suitable. The aspect of the citadel closest to a Chinese style was the decoration of the gates, which Finlayson noted as "handsome and ornamented in the Chinese style".[21] White recalled that the gates were reinforced by iron, a style that was common in Europe. The citadel was bordered on three sides by pre-existing waterways, increasing its defensive capacity.[21]

Nguyễn Ánh located his headquarters and palace inside the walls of the citadel. The palace itself was estimated by White to have covered an area of 3.25 hectares (8.0 acres), standing at the centre of the citadel on a green, enclosed by paling.[23] The structure was approximately 30 m (98 ft) long and 18 m (59 ft), built from brick and standing on a foundation around 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) above the ground, with a wooden staircase.[23] Each of the four sides of the palace was defended by a watchtower that stood approximately 9 m (30 ft).[23] After Nguyễn Ánh became emperor, he established his capital in Hue, and no longer used the palace,[24] which was used by the governor of the southern region.[23] The administration quarters continued to be used by the provincial mandarins and their paperwork was archived within.[24] A cemetery stood at the western end of the citadel, with prominent mandarins being interred there, while the arsenal was located in the northeast section in six large buildings. Soldiers lived in huts that were built throughout the grounds of the citadel.[25] White estimated that the fort was equipped with around 250 cannons, primarily made of brass.[26]

Impact on the Tây Sơn and the Nguyễn

Following the construction of the citadel, the Tây Sơn never again attempted to recapture the city—the building gave Nguyễn Ánh a further psychological advantage over his opponents.[27] The citadel helped to secure the southern region, which allowed Nguyễn Ánh to implement domestic programs to strengthen himself economically in preparation to fight the Tây Sơn. He used the newfound security to undertake agrarian reforms.[28] Due to Tây Sơn naval raids on the rice crop, the area had been suffering long term rice shortages.[29] Although the land was extremely fertile, the region was agriculturally underexploited because it had been occupied by Vietnamese people only relatively recently. Nguyễn Ánh's programs resulted in large amounts of previously idle land being cultivated. Large surpluses of grain, taxable by the state, were generated.[28]

By 1800, the increased agricultural productivity allowed Nguyễn Ánh to support an army of more than 30,000 soldiers and a navy of more than 1,200 vessels. The surplus from the state granary was used to facilitate the importing of supplies for military purposes.[30] Eventually, Nguyễn Ánh moved northwards and in 1802 he conquered all of Vietnam and became emperor, ruling under the name of Gia Long.[14][31][32]

Lê Văn Khôi revolt

The citadel was not used during the rule of Gia Long and the only military action occurred after his son had ascended the throne as Minh Mạng.[21] Years of tension between the monarch and General Lê Văn Duyệt, the governor of southern Vietnam,[33] came to a head after the death of the latter in 1831.[34] Tension between the pair surfaced when Gia Long made Minh Mạng the heir to the throne. Duyet had opposed the succession, favouring the enthronement of a young son of the late Prince Cảnh, the eldest of Gia Long's sons.[35]

After Gia Long's death, Minh Mạng and Duyệt clashed frequently. As the southern governor, Duyet had significant autonomy,[35] as only the centre of Vietnam was under direct royal rule.[36] Duyet was a supporter of Catholic missionaries, while Minh Mạng was a staunch Confucianist.[35] Duyet often disobeyed Minh Mạng's orders,[37] and the emperor attempted to reduce the Duyet's autonomous power, which became easier with the general's death in 1831.[34] The governor's post was abolished and the region was put under direct control.[34]

Following the integration of southern Vietnam into the central administration, newly appointed imperial officials arrived in Saigon. The new mandarins carried out a detailed inquiry into Duyệt's rule and claimed that widespread corruption and abuse of power took place.[34] Bạch Xuân Nguyên, the head of the inquiry, called for Duyet's posthumous prosecution, which resulted in 100 lashes being applied to his grave.[38][39] Many of Duyệt's subordinates were arrested and 16 of his family members were executed.[38] This action prompted the Duyệt's officials—fearful of their positions and security under the central system—to launch a revolt under the leadership of his adopted son Lê Văn Khôi.[38][39] Historical opinion is divided with scholars contesting whether the humiliation of Duyệt or the loss of southern autonomy was the main catalyst.[39]

On the night of May 18, 1833, Duyệt's supporters took control of the citadel, executing Nguyên and his subordinates. They then held a torch-lit ceremony at Duyệt's tomb, during which his adopted son Khôi formally rejected the imperial authority of Minh Mạng and declared his support for An Hoa, the son of Prince Cảnh. On the same evening, Khoi's men assassinated Nguyen Van Que, the newly appointed Governor-General who was overseeing the integration of the south into the central administration. All of the centrally appointed officials were killed or fled the citadel.[38] Surprise attacks caught the imperial garrisons off guard and within three days, all six southern provinces were in the hands of Khoi's forces.[38] Khoi convinced a French priest named Joseph Marchand to come and stay within the citadel, hoping that his presence would win over support from the local Catholics.[39] Khoi's support of An Hoa was also calculated to gain Catholic support, because Canh had converted to Catholicism.[40] He further called on Catholics to congregate in the citadel under his protection.[38] Vietnamese priests went on to lead Catholic armies in fighting off imperial forces as well providing messengers to communicate with the world outside their besieged citadel.[41]

In mid-1834, the imperial forces managed to finally repel the Siamese invaders and gained the upper hand over the rebels, regaining control of the southern countryside and besieging the rebel fortress.[39] Although Khôi died during the siege in November 1834,[39] the rebels defending the citadel of Saigon held out against imperial troops until September, 1835.[38] The rebel commanders put to death. In all, between 500 and 2,000 citadel defenders were captured and executed, including Marchand.[39]

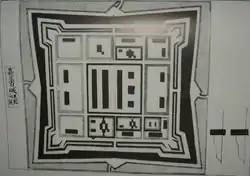

Second structure

Following the revolt, Minh Mạng ordered that the citadel be dismantled in 1835. He then ordered that a new citadel be built in its place, which was still square-shaped, but only had four towers. The six outer towers in the original citadel were discarded.[42] The destruction was seen as retribution for its use in the revolt. The new citadel, rebuilt in 1836,[42] was much smaller and was much more susceptible to enfilade bombardment from a nearby waterway.[43] The length of the square sides was 475 m (1,558 ft), surrounded by 20 m (66 ft) high walls, made from granite rocks, brick and earth.[44] The fort was surrounded by deep moats.

French invasion and destruction

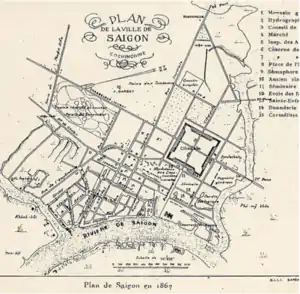

The process of Vietnam's colonisation began in 1858 when a Franco-Spanish force landed at Da Nang in central Vietnam and attempted to proceed to the capital Hue.[45] After becoming tied down, they sailed to the less defended south, targeting Saigon.[46] The southern offensive started on February 10, 1859 with a naval bombardment of Vũng Tàu. Within six days, the Europeans had levelled 12 Vietnamese fortresses and three river barriers. They then sailed along the Saigon River to the mouth of the Citadel of Saigon and opened fire with naval artillery from close range.[47] The fort was manned by 1,000 soldiers and stored enough rice to feed 10,000 defenders for an entire year.[48]

On February 17, 1859, the French warships opened fire on the citadel with artillery. This attack focused on the southeastern corner of the citadel, where most of the Vietnamese artillery had been installed.[48] The Vietnamese artillery commanders had miscalculated and had set up their cannons incorrectly, firing at excessively high angles. The cannons were not easily adjusted and thus the Vietnamese firepower was misdirected and ineffective.[48] At around 10:00, Captain Des Pallieres led 300 French soldiers in an infantry attack. They used bamboo ladders to scale the walls under artillery support from the river. The defenders were caught off guard by this manoeuvre and many fled in chaos.[48]

Most of the Vietnamese defence personnel were concentrated at the eastern gate of the citadel, where they stubbornly fought off the French. Rigault de Genouilly led 500 French troops in hand-to-hand combat for seven hours, having used explosives to breach the citadel. At 14:00, the French seized control of the citadel.[48] Two hours later, de Genouilly declared the citadel as the new general headquarters of the French forces.[49] The French seized a large arsenal. This included more than 200 cannons, 20,000 hand-held weapons such as firearms, pistols and swords, 100 tons of munitions, 80,000 tons of rice and 130,000 francs in cash.[49] Saltpetre, shot and sulphur were also seized.[43] The Vietnamese material losses were estimated to be around 20 million francs.[49] The citadel commander fled to another village before committing suicide.[49]

The Vietnamese attempted to reclaim the citadel by sending reinforcements. Vĩnh Long and Mỹ Tho sent 1,800 and 800 troops respectively, but French shelling prevented them from reaching the scene.[50] This left the 5,800-strong local self-defence militia to combat the French. These militia engaged in ambushing French patrols near the citadel, as well as evacuating local inhabitants, in order to create an open space close to their target.[51] The local militia were supported by wealthy southern landowners, who supplied them with food and resources.[52]

The French soldiers charged with holding the citadel soon became stretched by the guerrilla attacks on the military installation. De Genouilly had decided to withdraw some of his forces back to central Vietnam. In addition, the inland position of the French forces lessened their technological advantage. As a result, the French decided to evacuate and destroy the fort. This was achieved on March 8. Captain Deroulede used 32 chests of explosives.[53] He also razed the citadel by setting the rice granary ablaze, along with the weapons and munitions. The resulting fire was improbably claimed to have smoldered for a further three years.[43][53] The French withdrew to the outskirts of the city, before returning to central Vietnam.[54]

Citations

- McLeod, pp. 2–8.

- Mantienne, p. 520.

- Hall, p. 426.

- Hall, p. 423.

- Cady, p. 282.

- Buttinger, p. 266.

- McLeod, p. 7.

- Karnow, p. 75.

- Buttinger, pp. 233–241.

- Hall, pp. 426–429.

- Hall, p. 430.

- Hall, p. 429.

- Cady, p. 283.

- Karnow, p. 77.

- McLeod, p. 11.

- Mantienne, p. 521.

- Mantienne, p. 522.

- Cady, p. 284.

- Mantienne, p. 523.

- Crawfurd, p. 223.

- Mantienne, p. 524.

- Crawfurd, p. 224.

- White, p. 220.

- White, p. 221.

- White, p. 225.

- White, p. 224.

- Mantienne, p. 525.

- McLeod, p. 8.

- Mantienne, p. 530.

- McLeod, p. 9.

- Hall, p. 431.

- Buttinger, p. 241.

- McLeod, pp. 24–29.

- McLeod, p. 29.

- McLeod, p. 24.

- McLeod, p. 16.

- McLeod, p. 28.

- McLeod, p. 30.

- Buttinger, pp. 322–324.

- McLeod, p. 14.

- McLeod, p. 31.

- Mantienne, p. 526.

- Marr, p. 27.

- Nguyen, p. 178.

- Chapuis, p. 48.

- McLeod, p. 91.

- Marr, p. 44.

- Nguyen, p. 179.

- Nguyen, p. 180.

- Nguyen, p. 181.

- Nguyen, p. 182.

- Nguyen, p. 183.

- Nguyen, p. 184.

- Nguyen, p. 185.

References

- Buttinger, Joseph (1958). The Smaller Dragon: A Political History of Vietnam. New York City: Praeger.

- Cady, John F. (1964). Southeast Asia: Its Historical Development. New York City: McGraw Hill.

- Chapuis, Oscar (2000). The last emperors of Vietnam: from Tu Duc to Bao Dai. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31170-6.

- Crawfurd, John (1967) [1828]. Journal of an embassy to the courts of Siam and Cochin China. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-582698-1.

- Hall, D. G. E. (1981). A History of South-east Asia. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-24163-0.

- Karnow, Stanley (1997). Vietnam: A history. New York City: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- Marr, David G. (1970). Vietnamese anticolonialism, 1885–1925. Berkeley, California: University of California. ISBN 0-520-01813-3.

- Nguyen, Thanh Thi (1992). The French conquest of Cochinchina, 1858–1862. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Microfilms International.

- Mantienne, Frédéric (October 2003). "The Transfer of Western Military Technology to Vietnam in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries: The Case of the Nguyen". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Singapore: Cambridge University Press. 34 (3): 519–534. doi:10.1017/S0022463403000468.

- McLeod, Mark W. (1991). The Vietnamese response to French intervention, 1862–1874. New York City: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-93562-7.

- White, John (1824). A voyage to Cochin China. Oxford University Press.