Crying

Crying or weeping is the shedding of tears (or welling of tears in the eyes) in response to an emotional state, pain or a physical irritation of the eye. Emotions that can lead to crying include sadness, anger, and even happiness. The act of crying has been defined as "a complex secretomotor phenomenon characterized by the shedding of tears from the lacrimal apparatus, without any irritation of the ocular structures", instead, giving a relief which protects from conjunctivitis.[1] A related medical term is lacrimation, which also refers to non-emotional shedding of tears. Various forms of crying are known as sobbing, weeping, wailing, whimpering, bawling, and blubbering.[2]

For crying to be described as sobbing, it usually has to be accompanied by a set of other symptoms, such as slow but erratic inhalation, occasional instances of breath holding and muscular tremor.

A neuronal connection between the lacrimal gland and the areas of the human brain involved with emotion has been established.

Tears produced during emotional crying have a chemical composition which differs from other types of tears. They contain significantly greater quantities of the hormones prolactin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, and Leu-enkephalin,[3] and the elements potassium and manganese.[4]

Function

.jpg.webp)

The question of the function or origin of emotional tears remains open. Theories range from the simple, such as response to inflicted pain, to the more complex, including nonverbal communication in order to elicit altruistic helping behavior from others.[5][6] Some have also claimed that crying can serve several biochemical purposes, such as relieving stress and clearance of the eyes.[7] Crying is believed to be an outlet or a result of a burst of intense emotional sensations, such as agony, surprise or joy. This theory could explain why people cry during cheerful events, as well as very painful events.[8]

Individuals tend to remember the positive aspects of crying, and may create a link between other simultaneous positive events, such as resolving feelings of grief. Together, these features of memory reinforce the idea that crying helped the individual.[9]

In Hippocratic and medieval medicine, tears were associated with the bodily humors, and crying was seen as purgation of excess humors from the brain.[10] William James thought of emotions as reflexes prior to rational thought, believing that the physiological response, as if to stress or irritation, is a precondition to cognitively becoming aware of emotions such as fear or anger.

William H. Frey II, a biochemist at the University of Minnesota, proposed that people feel "better" after crying due to the elimination of hormones associated with stress, specifically adrenocorticotropic hormone. This, paired with increased mucosal secretion during crying, could lead to a theory that crying is a mechanism developed in humans to dispose of this stress hormone when levels grow too high.[11] However, tears have a limited ability to eliminate chemicals, reducing the likelihood of this theory.[12]

Recent psychological theories of crying emphasize the relationship of crying to the experience of perceived helplessness.[13] From this perspective, an underlying experience of helplessness can usually explain why people cry. For example, a person may cry after receiving surprisingly happy news, ostensibly because the person feels powerless or unable to influence what is happening.

Emotional tears have also been put into an evolutionary context. One study proposes that crying, by blurring vision, can handicap aggressive or defensive actions, and may function as a reliable signal of appeasement, need, or attachment.[14] Oren Hasson, an evolutionary psychologist in the zoology department at Tel Aviv University believes that crying shows vulnerability and submission to an attacker, solicits sympathy and aid from bystanders, and signals shared emotional attachments.[15]

Another theory that follows evolutionary psychology is given by Paul D. MacLean, who suggests that the vocal part of crying was used first as a "separation cry" to help reunite parents and offspring. The tears, he speculates, are a result of a link between the development of the cerebrum and the discovery of fire. MacLean figures that since early humans must have relied heavily on fire, their eyes were frequently producing reflexive tears in response to the smoke. As humans evolved the smoke possibly gained a strong association with the loss of life and, therefore, sorrow.[16]

In 2017 Carlo Bellieni analysed the weeping behavior, and concluded that most animals can cry but only humans have psychoemotional shedding of tears, also known as "weeping". Weeping is a behavior that induces empathy perhaps with the mediation of the mirror neurons network, and influences the mood through the release of hormones elicited by the massage effect made by the tears on the cheeks, or through the relief of the sobbing rhythm.[17] Many ethologists would disagree.[18]

Biological response

It can be very difficult to observe biological effects of crying, especially considering many psychologists believe the environment in which a person cries can alter the experience of the crier. However, crying studies in laboratories have shown several physical effects of crying, such as increased heart rate, sweating, and slowed breathing. Although it appears that the type of effects an individual experiences depends largely on the individual, for many it seems that the calming effects of crying, such as slowed breathing, outlast the negative effects, which could explain why people remember crying as being helpful and beneficial.[19]

Globus sensation

The most common side effect of crying is feeling a lump in the throat of the crier, otherwise known as a globus sensation.[20] Although many things can cause a globus sensation, the one experienced in crying is a response to the stress experienced by the sympathetic nervous system. When an animal is threatened by some form of danger, the sympathetic nervous system triggers several processes to allow the animal to fight or flee. This includes shutting down unnecessary body functions, such as digestion, and increasing blood flow and oxygen to necessary muscles. When an individual experiences emotions such as sorrow, the sympathetic nervous system still responds in this way.[21] Another function increased by the sympathetic nervous system is breathing, which includes opening the throat in order to increase air flow. This is done by expanding the glottis, which allows more air to pass through. As an individual is undergoing this sympathetic response, eventually the parasympathetic nervous system attempts to undo the response by decreasing high stress activities and increasing recuperative processes, which includes running digestion. This involves swallowing, a process which requires closing the fully expanded glottis to prevent food from entering the larynx. The glottis, however, attempts to remain open as an individual cries. This fight to close the glottis creates a sensation that feels like a lump in the individual's throat.[22]

Other common side effects of crying are quivering lips, a runny nose, and an unsteady, cracking voice.

Frequency of crying

According to the German Society of Ophthalmology, which has collated different scientific studies on crying, the average woman cries between 30 and 64 times a year, and the average man cries between 6 and 17 times a year.[23]

Men tend to cry for between two and four minutes, and women cry for about six minutes. Crying turns into sobbing for women in 65% of cases, compared to just 6% for men. Until adolescence, however, no difference between the sexes was found.[24][23]

The gap between how often men and women cry is larger in wealthier, more democratic, and feminine countries.[25]

In infants

.jpg.webp)

Infants can shed tears at approximately 4–8 weeks of age.[26]

Although crying is an infant's mode of communication, it is not limited to a monotonous sound. There are three different types of cries apparent in infants. The first of these three is a basic cry, which is a systematic cry with a pattern of crying and silence. The basic cry starts with a cry coupled with a briefer silence, which is followed by a short high-pitched inspiratory whistle. Then, there is a brief silence followed by another cry. Hunger is a main stimulant of the basic cry. An anger cry is much like the basic cry; however, in this cry, more excess air is forced through the vocal cords, making it a louder, more abrupt cry. This type of cry is characterized by the same temporal sequence as the basic pattern but distinguished by differences in the length of the various phase components. The third cry is the pain cry, which, unlike the other two, has no preliminary moaning. The pain cry is one loud cry, followed by a period of breath holding. Most adults can determine whether an infant's cries signify anger or pain.[27] Most parents also have a better ability to distinguish their own infant's cries than those of a different child.[28] A 2009 study found that babies mimic their parents' pitch contour. French infants wail on a rising note while German infants favor a falling melody.[29] Carlo Bellieni found a correlation between the features of babies' crying and the level of pain, though he found no direct correlation between the cause of crying and its characteristics.[30]

T. Berry Brazelton has suggested that overstimulation may be a contributing factor to infant crying and that periods of active crying might serve the purpose of discharging overstimulation and helping the baby's nervous system regain homeostasis.[31] [32]

Sheila Kitzinger found a correlation between the mother's prenatal stress level and later amount of crying by the infant. She also found a correlation between birth trauma and crying. Mothers who had experienced obstetrical interventions or who were made to feel powerless during birth had babies who cried more than other babies. Rather than try one remedy after another to stop this crying, she suggested that mothers hold their babies and allow the crying to run its course.[33] Other studies have supported Kitzinger's findings. Babies who had experienced birth complications had longer crying spells at three months of age and awakened more frequently at night crying.[34][35]

Based on these various findings, Aletha Solter has proposed a general emotional release theory of infant crying. When infants cry for no obvious reason after all other causes (such as hunger or pain) are ruled out, she suggests that the crying may signify a beneficial stress-release mechanism. She recommends the "crying-in-arms" approach as a way to comfort these infants.[36][37][38] Another way of comforting and calming the baby is to mimic the familiarity and coziness of mother's womb. Dr. Robert Hamilton developed a technique to parents where a baby may be calmed and stop crying in 5 seconds.[39]

Categorizing dimensions

There have been many attempts to differentiate between the two distinct types of crying: positive and negative. Different perspectives have been broken down into three dimensions to examine the emotions being felt and also to grasp the contrast between the two types.[40]

Spatial perspective explains sad crying as reaching out to be "there", such as at home or with a person who may have just died. In contrast, joyful crying is acknowledging being "here." It emphasized the intense awareness of one's location, such as at a relative's wedding.[40]

Temporal perspective explains crying slightly differently. In temporal perspective, sorrowful crying is due to looking to the past with regret or to the future with dread. This illustrated crying as a result of losing someone and regretting not spending more time with them or being nervous about an upcoming event. Crying as a result of happiness would then be a response to a moment as if it is eternal; the person is frozen in a blissful, immortalized present.[40]

The last dimension is known as the public-private perspective. This describes the two types of crying as ways to imply details about the self as known privately or one's public identity. For example, crying due to a loss is a message to the outside world that pleads for help with coping with internal sufferings. Or, as Arthur Schopenhauer suggested, sorrowful crying is a method of self-pity or self-regard, a way one comforts oneself. Joyful crying, in contrast, is in recognition of beauty, glory, or wonderfulness.[40]

Religious views on crying

.jpg.webp)

The Shia Ithna Ashari (Muslims who believe in twelve Imams after Muhammad) consider crying to be an important responsibility towards their leaders who were martyred. They believe a true lover of Imam Hussain can feel the afflictions and oppressions Imam Hussain suffered; his feelings are so immense that they break out into tears and wail. The pain of the beloved is the pain of the lover. Crying on Imam Husain is the sign or expression of true love. The Imams of Shias have encouraged crying especially on Imam Husaain and have informed about rewards for this act. They support their view through a tradition (saying) from Muhammad who said: (On the Day of Judgment, a group would be seen in the most excellent and honourable of states. They would be asked if they were of the Angels or of the Prophets. In reply they would state): "We are neither Angels nor Prophets but of the indigent ones from the ummah of Muhammad". They would then be asked: "How then did you achieve this lofty and honourable status?" They would reply: "We did not perform very many good deeds nor did we pass all the days in a state of fasting or all the nights in a state of worship but yes, we used to offer our (daily) prayers (regularly) and whenever we used to hear the mention of Muhammad, tears would roll down our cheeks".(Mustadrak al‑Wasail, vol 10, pg. 318)

In Orthodox and Catholic Christianity, tears are considered to be a sign of genuine repentance, and a desirable thing in many cases. Tears of true contrition are thought to be sacramental, helpful in forgiving sins, in that they recall the Baptism of the penitent.[41][42]

Type of tears

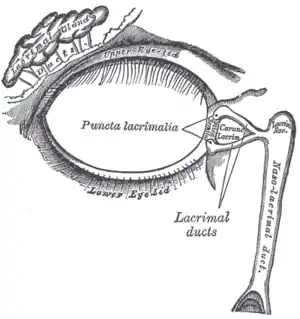

There are three types of tears: basal tears, reflexive tears, and psychic tears. Basal tears are produced at a rate of about 1 to 2 microliters a minute, and are made in order to keep the eye lubricated and smooth out irregularities in the cornea. Reflexive tears are tears that are made in response to irritants to the eye, such as when chopping onions or getting poked in the eye. Psychic tears are produced by the lacrimal system and are the tears expelled during emotional states.[43]

Disorders related to crying

- Baby colic, where an infant's excessive crying has no obvious cause or underlying medical disorder.

- Bell's palsy, where faulty regeneration of the facial nerve can cause sufferers to shed tears while eating.[44]

- Cri du chat, where the characteristic cry of affected infants, which is similar to that of a meowing kitten, is due to problems with the larynx and nervous system.

- Familial dysautonomia, where there can be a lack of overflow tears (alacrima), during emotional crying.[45]

- Pathological laughing and crying, where the patients experience uncontrollable episodes of laughing, crying, or in some cases both.

- Dyslacrymia, where there is a lack of crying and emotional processing.

References

- Patel, V. (1993). "Crying behavior and psychiatric disorder in adults: a review". Compr Psychiatry. 34 (3): 206–11. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(93)90049-A. PMID 8339540. Quoted by Michelle C.P. Hendriks, A.J.J.M. Vingerhoets in Crying: is it beneficial for one's well-being?

- "List of 426 Sets of Synonyms and How they Differ in Meaning". Paulnoll.com. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

- Anton Skorucak, MS. "The Science of Tears". ScienceIQ.com. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- Walter, Chip (December 2006). "Why do we cry?". Scientific American Mind. 17 (6): 44. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind1206-44.

- "On the Origin of Crying and Tears". Human Ethology Newsletter. 5 (10): 5–6. June 1989.

- Stadel, M; Daniels, JK; Warrens, MJ; Jeronimus, BF (2019). "The gender-specific impact of emotional tears". Motivation and Emotion. 1 (1): 696–704. doi:10.1007/s11031-019-09771-z.

- Doheny, Kathleen. "Why We Cry: The Truth About Tearing Up". WebMD. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- "Crying; The Mystery of Tears" personal page of Frey WH with quote from his book Archived 2008-05-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Carey, Benedict (2 February 2009). "The Muddled Tracks of All Those Tears". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Lutz, Tom (2001). Crying : the natural and cultural history of tears. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393321036.

- "Emotional Freedom". Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- Murube J, Murube L, Murube A (1999). "Origin and types of emotional tearing" (PDF). Eur J Ophthalmol. 9 (2): 77–84. doi:10.1177/112067219900900201. PMID 10435417. S2CID 21272166.

Juan Murube, president of the Spanish Society of Ophthalmology, reports that the amount of blood passing through the lacrimal glands is tiny in comparison to the body's five liters of blood, and unlike other minor bodily excretion methods like breathing and perspiration, tears are mostly reabsorbed into the body.

- Miceli, M.; Castelfranchi, C. (2003). "Crying: discussing its basic reasons and uses". New Ideas in Psychology. 21 (3): 247–73. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2003.09.001.

- Choi, Charles Q. (28 August 2009). "New Theory for Why We Cry". Live Science. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- "Why Cry? Evolutionary Biologists Show Crying Can Strengthen Relationships". Science Daily. Tel Aviv University. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Lutz, Tom (1999). Crying : the natural and cultural history of tears (1. ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0-393-04756-3.

- Bellieni CV (2017). "Meaning and importance of weeping". New Ideas in Psychology. 46: 72–76. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2017.06.003.

- De Waal, F (2019). Mama's last hug: Animal emotions and what they tell us about ourselves. W.W. Norton & Company, New York. ISBN 9780393635065.

- "Cry Me A River: The Psychology of Crying". Science Daily. Association for :Psychological Science. 19 December 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- "What Causes a Lump in the Throat Feeling? Globus Sensation". Heath Talk. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Glass, Don (15 January 2007). "A Lump in Your Throat". Moment of Science.

- Onken, Michael (16 February 1997). "What causes the 'lump' in your throat when you cry?". MadSci. Washington University Medical School. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- "Frauen und Männer weinen anders [German: Woman and Men Cry Differently]" (PDF). Pressearchiv 2009. Deutsche Ophtalmologische Gesellschaft. October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Women cry more than men, and for longer, study finds". The Telegraph. London. 15 October 2009.

- van Hemert, Dianne A.; van de Vijver, Fons J. R.; Vingerhoets, Ad J. J. M. (2011-11-01). "Culture and Crying: Prevalences and Gender Differences" (PDF). Cross-Cultural Research. 45 (4): 399–431. doi:10.1177/1069397111404519. ISSN 1069-3971. S2CID 53367887.

- Bylsma, Lauren M.; Gračanin, Asmir; Vingerhoets, Ad J. J. M. (2018-04-23). "The neurobiology of human crying". Clinical Autonomic Research. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 29 (1): 63–73. doi:10.1007/s10286-018-0526-y. ISSN 0959-9851. PMC 6201288. PMID 29687400.

- Zeskind, P. S.; Klein, L.; Marshall, T. R. (Nov 1992). "Adults' perceptions of experimental modifications of durations of pauses and expiratory sounds in infant crying". Developmental Psychology. 28 (6): 1153–1162. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.6.1153.

- Santrock, John W. (2007). "Crying". A Topical Approach to Lifespan Development (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages. pp. 351–2. ISBN 978-0-07-338264-7.

- Mampe, B.; Friederici, A.D.; Christophe, A.; Wermke, K. (December 2009). "Newborns' cry melody is shaped by their native language". Curr. Biol. 19 (23): 1994–7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.064. PMID 19896378. S2CID 2907126.

- Cressman R, Garay J, Varga Z (November 2003). "Evolutionarily stable sets in the single-locus frequency-dependent model of natural selection". J Math Biol. 47 (5): 465–82. doi:10.1007/s00285-003-0217-7. PMID 14605860. S2CID 27778902.

- T. Berry Brazelton (1985). "Application of Cry Research to Clinical Perspectives". Infant Crying. Springer, Boston, MA: 325–340. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-2381-5_15. ISBN 978-1-4612-9455-9.

- Brazelton, T.B. (1992). Touchpoints. New York: Perseus.

- Kitzinger, S. (1989). The Crying Baby. New York: Viking.

- de Weerth C, Buitelaar JK (September 2007). "Childbirth complications affect young infants' behavior". Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 16 (6): 379–88. doi:10.1007/s00787-007-0610-7. PMID 17401610.

- Keller H, Lohaus A, Vîlker S, Cappenberg M, Chasiotis A (1998). "Relationships between infant crying, birth complications, and maternal variables". Child: Care, Health and Development. 24 (5): 377–394. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00090.x. PMID 9728284.

- Solter, A. (1995). "Why do babies cry?" Pre- and Perinatal Psychology Journal, 10 (1), 21–43.

- Solter, A. (1998). Tears and Tantrums: What to Do When Babies and Children Cry. Goleta, CA: Shining Star Press. ISBN 978-0961307363

- Solter, A. (2004). Crying for comfort: distressed babies need to be held." Mothering, Issue 122 January/February, 24–29.

- "How To Calm A Crying Baby Tips for Parents and Babysitters". NannySOS. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- Katz, Jack (1999). How emotions work. Chicago [u.a.]: Univ. of Chicago Press. p. 182. ISBN 0-226-42599-1.

- Design by (2014-06-18). "On Prayer XVII: On Compunction and Tears | A Russian Orthodox Church Website". Pravmir.com. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

- "Crying". Nytimes.com. 1992-03-10. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

- Lutz, Tom (1999). Crying : the natural and cultural history of tears (1. ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 68. ISBN 0-393-04756-3.

- Morais Pérez, D.; Dalmau Galofre, J.; Bernat Gili, A.; Ayerbe Torrero, V. (1990). "[Crocodile tears syndrome]". Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp (in Spanish). 41 (3): 175–7. PMID 2261223.

- Felicia B. Axelrod; Gabrielle Gold-von Simson (October 3, 2007). "Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies: types II, III, and IV". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2 (39): 39. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-39. PMC 2098750. PMID 17915006.

Further reading

- Corless, Damian (8 August 2008). "Boys Don't Cry?". Irish Independent.: examines the taboo that still surrounds public crying.

- Flintoff, John-Paul (30 August 2003). "Why We Cry". The Age. Melbourne.

- Frey, William H.; Langseth, Muriel (1985). Crying: The Mystery of Tears. Minneapolis: Winston Press. ISBN 0-86683-829-5.

- Lutz, Tom (1999). Crying: The Natural and Cultural History of Tears. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-04756-3.

- Walter, Chip (2006). "Why Do We Cry?". Scientific American. 17 (6): 44. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind1206-44.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crying. |

- Stepp, Gina (14 January 2009). "It's No Party, But I'll Cry if I Want To". Vision Media. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009.