Delorazepam

Delorazepam, also known as chlordesmethyldiazepam and nordiclazepam, is a drug which is a benzodiazepine and a derivative of desmethyldiazepam.[1] It is marketed in Italy, where it is available under the trade name EN and Dadumir.[2] Delorazepam (chlordesmethyldiazepam) is also an active metabolite of the benzodiazepine drugs diclazepam and cloxazolam.[3] Adverse effects may include hangover type effects, drowsiness, behavioural impairments[4][5] and short-term memory impairments.[6] Similar to other benzodiazepines delorazepam has anxiolytic,[7] skeletal muscle relaxant,[8] hypnotic[4] and anticonvulsant properties.[9]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | EN, Dadumir |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 87% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 60–140 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.018.884 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

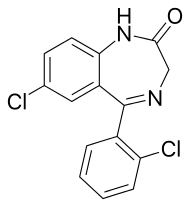

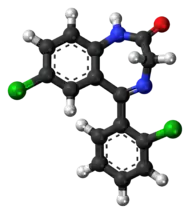

| Formula | C15H10Cl2N2O |

| Molar mass | 305.16 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Indications

Delorazepam is mainly used as an anxiolytic because of its long elimination half-life; showing superiority over the short-acting drug lorazepam.[10] In comparison with the antidepressant drugs, paroxetine and imipramine, delorazepam was found to be more effective in the short-term but after 4 weeks the antidepressants showed superior anti-anxiety effects.[11]

Delorazepam is also used as a premedication for dental phobia for its anxiolytic properties.[12] High doses of Delorazepam may be administered the night before a dental (or other medical) procedure in order to provide relief from anxiety-associated insomnia that night with the effects persisting long enough to sufficiently treat anxiety the next day.

Delorazepam has also demonstrated effectiveness in treating alcohol withdrawal.[13]

Availability

Delorazepam is available in tablet and liquid drop formulations. The liquid drop formulation is absorbed more quickly and has improved bioavailibility.[14]

Pharmacology

Delorazepam is well absorbed after administration, reaching peak plasma levels within 1 – 2 hours. It has a very long elimination half-life and can still be detected 72 hours after dosing.[15] Bioavailability is about 77 percent. Peak plasma levels occur at just over one hour after administration. Significant accumulation occurs of delorazepam due to its slow metabolism;[16] the elderly metabolise delorazepam and its active metabolite slower than younger individuals, resulting in a dose of delorazepam accumulating faster and peaking at a higher plasma concentration than an equal dose administered to a younger individual. The elderly also have a poorer response to the therapeutic effects and a higher rate of adverse effects. The elimination half-life of delorazepam is 80–115 hours. The active metabolite of delorazepam is lorazepam and represents about 15 - 24 percent of the parent drug (delorazepam).[14][17][18] The pharmacokinetics of delorazepam are not altered if it is taken with food, except for some slowing of absorption.[19] Delorazepams potency is approximately equal to that of lorazepam, being ten times more potent by weight than diazepam (1 mg delorazepam = 1 mg lorazepam = 10 mg diazepam), typical doses range from 0.5 mg - 2 mg. Treatment is generally initiated at 1 mg for healthy adults and 0.5 mg in pediatric and geriatric patients and patients with mild renal impairment, treatment is contraindicated in patients with moderate or severe renal impairment.

Side effects and contraindications

Delorazepam hosts all the classic side-effects of GABAA full agonists (such as most benzodiazepines). These include sedation/somnolence, dizziness/ataxia, amnesia, reduced inhibition, increased talkativeness/sociability, euphoria, impaired judgement, hallucinations, and respiratory depression. Paradoxical reactions including increased anxiety, excitation, and aggression may occur and are more common in elderly, pediatric, and schizophrenic patients. In rare instances, delorazepam may cause suicidal ideation and actions.

Long term use of delorazepam (as well as all other benzodiazepines) has been found to increase long term cognitive deficits (persisting longer than sixth months) which some researchers claim to be permanent. Short term use may occasionally cause depression and the risk of depressive symptoms occurring increases considerably with longer terms of use, delorazepam is not intended to be used for more than 2–4 weeks unless it used only occasionally on an as-needed basis. When being used on an as-needed basis the need for delorazepam therapy should be re-evaluated each time a new prescription for delorazepam is issued, and alternative medications should be considered if patients begin to take delorazepam habitually (many days in a row).

The most serious effect of long term delorazepam use is dependence, with withdrawal symptoms which mimic delirium tremens presenting when delorazepam use is discontinued. Although the withdrawal effects from delorazepam are generally less severe than its shorter-acting counterparts, they can be life-threatening. Slow de-titration of delorazepam over a period of weeks or months is generally suggested to minimize the severity of withdrawal. Psychological effects of withdrawal such as rebound anxiety and insomnia have been known to persist for months after physical dependence has been successfully treated.

Delorazepam is contraindicated in those with severe schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorders, those with a known allergy or hypersensitivity to delorazepam or related benzodiazepines, and those with moderate to severe renal impairment (delorazepam is sometimes administered at a reduced dose to patients with mild renal impairment). Delorazepam is generally considered to be contraindicated in patients with severe acute or chronic illnesses but is occasionally used in the palliative care of terminal patients during their last days/weeks of life.

Patients with a history of drug and/or alcohol abuse are believed to have an increased risk of abusing delorazepam (as well as all other benzodiazepines), this must be considered when a physician prescribes delorazepam to such patients. Although all patients being treated with delorazepam should be routinely monitored for signs of abuse and diversion of medication, increased monitoring of patients with a history of drug and/or alcohol abuse is always warranted. Benzodiazepine abuse in patients taking them as prescribed on an as-needed basis for chronic/refractory anxiety, insomnia, and intermittent muscle spasms has occurred and generally occurs very slowly, becoming evident only after months or years since the initiation of therapy. Monitoring of patients actively using delorazepam should never be discontinued even if the patients has been stable on the medication for many months or years.

Caution must be used when delorazepam is administered alongside other sedative medications (ex. opiates, barbiturates, z-drugs, and phenothiazines) due to an increased risk of sedation, ataxia, and (potentially fatal) respiratory depression. Although overdoses of benzodiazepines alone rarely result in death, the combination of benzodiazepines and other sedatives (particularly other gabaminergic drugs such as barbiturates and alcohol) is far more likely to result in death.

Special cautions

People with renal failure on haemodialysis have a slow elimination rate and a reduced volume of distribution of the drug.[20] Liver disease has a profound effect on the elimination rate of delorazepam, resulting in the half-life almost doubling to 395 hours, whereas healthy patients showed an elimination half-life of 204 hours on average. Caution is recommended when using delorazepam in patients with liver disease.[21]

See also

- Benzodiazepine

- Phenazepam—7-bromo-analog

- Nordiclazepam is used as the precursor with which to make Uldazepam via the thionamide.

References

- Govoni S, Fresia P, Spano PF, Trabucchi M (November 1976). "Effect of desmethyldiazepam and chlordesmethyldiazepam on 3',5'-cyclic guanosine monophosphate levels in rat cerebellum". Psychopharmacology. 50 (3): 241–4. doi:10.1007/BF00426839. PMID 188062. S2CID 32711086.

- "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- Oliveira-Silva D, Oliveira CH, Mendes GD, Galvinas PA, Barrientos-Astigarraga RE, De Nucci G (December 2009). "Quantification of chlordesmethyldiazepam by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: application to a cloxazolam bioequivalence study". Biomedical Chromatography. 23 (12): 1266–75. doi:10.1002/bmc.1249. PMID 19488979.

- Zimmermann-Tansella C, Tansella M, Lader M (October 1976). "The effects of chlordesmethyldiazepam on behavioral performance and subjective judgment in normal subjects". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 16 (10 Pt 1): 481–88. PMID 977791.

- Cesco G, Giannico S, Fabbruci I, Scaggiante L, Montanaro N (1977). "Single-blind evaluation of hypnotic activity of chlordesmethyldiazepam in No-placebo-reactor medical patients". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 27 (1): 146–8. PMID 322671.

- Scarone S, Strambi LF, Cazzullo CL (1981). "Effects of two dosages of chlordesmethyldiazepam on mnestic-information processes in normal subjects". Clinical Therapeutics. 4 (3): 184–91. PMID 6796270.

- Andreoli V, Maffei F, Montanaro N, Morandini G (February 1977). "Double-blind cross-over clinical comparison of two 2'-chloro benzodiazepines: 7-chloro-5-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,3-dihydro-2H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one (chlordesmethyldiazepam) versus 7-chloro-5-(o-chlorophenyl)-1,3-dihydro-3-hydroxy-2H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one (lorazepam) in neurotic anxiety". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 27 (2): 436–9. PMID 16622.

- Kostowski W, Płaźnik A, Puciłowski O, Trzaskowska E, Lipińska T (1981). "Some behavioral effects of chlorodesmethyldiazepam and lorazepam". Polish Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacy. 33 (6): 597–602. PMID 6127668.

- Curatolo P, Cusmai R, Trasatti G, Sciarretta A (1985). "[Effects of intravenous administration of chlordesmethyldiazepam on paroxysmal intercritical activity in various electroclinical forms of infantile epilepsy]". Rivista di Neurologia. 55 (6): 377–86. PMID 3938567.

- Bertin I, Colombo G, Furlanut M, Benetello P (1989). "Double-blind placebo cross-over study of long-acting (chlordesmethyldiazepam) versus short-acting (lorazepam) benzodiazepines in generalized anxiety disorders". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology Research. 9 (3): 203–8. PMID 2568350.

- Rocca P, Fonzo V, Scotta M, Zanalda E, Ravizza L (May 1997). "Paroxetine efficacy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 95 (5): 444–50. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09660.x. PMID 9197912. S2CID 28985221.

- Manani G, Baldinelli L, Cordioli G, Consolati E, Luisetto F, Galzigna L (1995). "Premedication with chlordemethyldiazepam and anxiolytic effect of diazepeam in implantology". Anesthesia Progress. 42 (3–4): 107–12. PMC 2148912. PMID 8934975.

- Cazzato G, Gioseffi M, Torre P, Coppola N (Nov–Dec 1982). "[Prevention and therapy of delirium tremens with tiapride and chlordesmethyldiazepam]". Rivista di Neurologia. 52 (6): 331–42. PMID 6130594.

- Bareggi SR, Truci G, Leva S, Zecca L, Pirola R, Smirne S (1988). "Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of intravenous and oral chlordesmethyldiazepam in humans". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 34 (1): 109–12. doi:10.1007/BF01061430. PMID 2896126. S2CID 1574555.

- Dal Bo L, Marcucci F, Mussini E, Perbellini D, Castellani A, Fresia P (1980). "Plasma levels of chlorodesmethyldiazepam in humans". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition. 1 (3): 123–6. doi:10.1002/bdd.2510010306. PMID 6778522. S2CID 33627270.

- European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1988, Volume 34, Issue 1, pp 109-112 'Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of intravenous and oral chlordesmethyldiazepam in humans' S.R.Bareggi, G.Truci, S.Leva, L.Zecca, R.Pirola, S.Smirne

- Bareggi SR, Nielsen NP, Leva S, Pirola R, Zecca L, Lorini M (1986). "Age-related multiple-dose pharmacokinetics and anxiolytic effects of delorazepam (chlordesmethyldiazepam)". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology Research. 6 (4): 309–14. PMID 2875955.

- Bareggi SR, Pirola R, Leva S, Zecca L (1986). "Pharmacokinetics of chlordesmethyldiazepam after single-dose oral administration in humans". European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 11 (3): 171–4. doi:10.1007/BF03189844. PMID 3102240. S2CID 19525288.

- Bareggi SR, Pirola R, Truci G, Leva S, Smirne S (April 1988). "Effect of food on absorption of chlordemethyldiazepam". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 38 (4): 561–2. PMID 2900012.

- Sennesael J, Verbeelen D, Vanhaelst L, Pirola R, Bareggi SR (1991). "Pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral chlordesmethyldiazepam in patients on regular haemodialysis". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 41 (1): 65–8. doi:10.1007/BF00280109. PMID 1782980. S2CID 31251671.

- Bareggi SR, Pirola R, Potvin P, Devis G (1995). "Effects of liver disease on the pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral chlordesmethyldiazepam". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 48 (3–4): 265–8. doi:10.1007/bf00198309. PMID 7589052. S2CID 19145264.