Demonstration of 20 June 1792

The Demonstration of 20 June 1792 (French: Journée du 20 juin 1792) was the last peaceful attempt made by the people of Paris to persuade King Louis XVI of France to abandon his current policy and attempt to follow what they believed to be a more empathetic approach to governing. The demonstration occurred during the French Revolution. Its objectives were to convince the government to enforce the Legislative Assembly's rulings, defend France against foreign invasion, and preserve the spirit of the French Constitution of 1791. The demonstrators hoped that the king would withdraw his veto and recall the Girondin ministers.

| The Demonstration of 20 June 1792 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolution | |||||

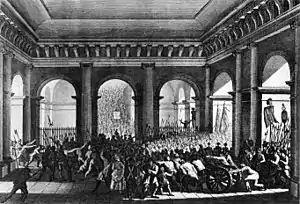

Le Peuple pénètre dans le Château des Tuileries, Jan Bulthuis, 1800, Musée de la Révolution française. | |||||

| |||||

The Demonstration was the last phase of the unsuccessful attempt to establish a constitutional monarchy in France. After the Insurrection of 10 August 1792, the monarchy fell.

Background

Under the Girondin ministry, on 20 April 1792, war was declared against Austria. The resulting war, which would last almost continuously until 1815 and shake the very foundations of Europe, put new life into the revolutionary movement in France. The monarchy was its first victim.[1]

Of even greater consequence was a major economic crisis. As it struck France's towns, it again set the masses in motion. The crisis was caused by inflation rather than scarcity as past crises, as the currency in circulation had increased by 600 million since October 1792. With continued depreciation of the assignat, the exchange rate fell even more rapidly. By March 1793, French money once worth British £100 would buy only £50 worth of goods in Paris. The flood of paper notes, misused by speculators, aggravated unrest.[2]

Military setbacks

France declared war on the King of Bohemia and Hungary (Austria) on 20 April 1792. The French troops and their leadership were inadequate from the beginning, leaving the French army in a state of total disarray.[1] The front-line regiments were insufficiently strong because most men preferred to enlist in volunteer battalions, which were better paid, elected their own officers, and could disband after the campaign.

But despite these attractions, even the volunteer battalions were slow to form. Few volunteers were truly motivated to fight. Frequently, National Guardsmen, not wishing to leave their homes, offered bonuses to convince others to take their place and to muster the necessary quotas. Consequently, it took time for a sufficient quantity of men to enlist. Equipment was furnished by local authorities but arrived slowly, and insufficient arms were available.[3]

French general Charles François Dumouriez thought the army could get its training in combat. He argued that the enemy had no more than 30,000 men to throw into a campaign, and that foreign troops would be arranged in a cordon from the sea to Lorraine. He proposed to break through this barrier: one column each from Furnes, Lille, Valenciennes, and Givet, totalling more than 50,000 men, would set out on 29 April towards the enemy line.

The other generals, however, were trained for regular war and rejected this plan. Additionally, the officers distrusted their undisciplined troops, while the troops were suspicious of their generals in return. Out of 9,000 officers, at least half had already emigrated, and a few more deserted on the eve of the offensive. In May, several others took three regiments into the enemy camp.

The first military confrontation, the capture of Porrentruy in Switzerland on 28 April, was a small French success. However, in the Battle of Marquain in the Austrian Netherlands on 29 April, Théobald Dillon and Armand Louis de Gontaut ordered a retreat at the sight of the first Austrian troops. Their men cried treason and disbanded; Dillon was murdered at Lille.[4]

The generals blamed these setbacks on a lack of discipline and on a ministry that tolerated such conditions. In reply, the Gironde ordered Dillon's murderers prosecuted, along with Jean-Paul Marat, who had been exhorting the soldiers to get rid of their generals. A new decree tightened military justice and authorized the generals to issue regulations bearing penalties for infractions. The decree undeniably marked a surrender of legislative power, but to no avail. On 18 May, the leaders of the armies, meeting at Valenciennes, disregarded repeated orders from the ministry and declared an offensive impossible, advising the king to make immediate peace.[4]

As a result, the generals suspended the offensive. In May, a whole corps, the Royal-Allemand, defected to the enemy. Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, commander of the Armée du Nord, resigned. Assembly member Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette went as far as deliberate treachery. Secretly, he proposed to the Austrians that fighting should be suspended so that he could turn his army against Paris in order to disperse the Jacobins and establish a strong regime.[5]

Decrees of the Assembly

The Girondins saw no choice but to fall back on the policy of intimidation that had brought them to power. With this goal in mind, the Assembly passed three decrees.

The first decree was directed against the priests who had refused the oath to the civil constitution. Religious disturbances necessitated some decisive action against them, as the state could not be preserved if it continued treating as members of society those who were evidently seeking to dissolve it. One proposal suggested assembling the non-juring priests in the capitals of the departments, but this would have meant creating eighty-three centers of discord, fanaticism, and counter-revolution. The majority of the Assembly concluded the country must be purged. After several days of discussion, fearing the overthrow of the constitution, the Assembly passed the following decree on 27 May 1792: "When twenty active citizens of a canton shall demand that a nonjuring priest leave the realm, the directory of the department must order his deportation if the directory agrees with the petition. If the directory does not agree with the demand of the twenty citizens, it shall determine through committees whether the presence of the priest is a threat to public peace, and if the opinion of the committee supports the demand of the twenty petitioners, the deportation shall be ordered." This decree made the clergy choose between the oath to the constitution and deportation.[6]

This measure was followed by another directed against the king's bodyguards. The guard had revealed anti-revolutionary sentiments and had uttered threats against the Assembly. The guard was believed to be royalist in its sympathies; wholly devoted to the person of the king; hostile to the government; and wholly lacking in esprit de corps. Assembly member Claude Basire proposed the guard's dissolution, charging its officers with orgies and a plan for carrying away the king. He asked to be allowed to give proof of his accusations the next day. Meanwhile, fellow Assembly member François Chabot declared that he had 182 documents proving the existence of a plot to dissolve the Assembly, set for 27 May. In response, the Assembly decreed that its sessions should be continuous; that the Paris guard should be doubled; and that Paris's mayor, Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve, should be required to make a daily report on the state of the capital city. Regarding the king's bodyguards, Assembly member Marguerite-Élie Guadet articulated three arguments for the guard's dissolution: first, that it was illegally organized; second, that its chiefs sought to inspire revolt; and third, that the majority favored a counter-revolution. On 29 May 1792, the Assembly decreed that the guard should be dissolved and its commander, the Duc de Brissac, arrested. This decree was executed immediately.[7]

The third decree provided for a camp of 20,000 fédérés (French National Guardsmen) to be assembled on 14 June near Paris. French general Joseph Marie Servan de Gerbey made this proposition on 4 June, reportedly without consulting either his colleagues or the king. He argued that the initiative was necessary to establish tranquility in the country. The decree itself stated that its purpose was to improve fraternity between the departments of France. However, discussions in the Assembly indicated that the decree's purpose was to ensure public security. As allies were approaching from without and enemies of the constitution were plotting from within, Paris and the Assembly needed protection.[8]

Fall of the Girondin Ministry

King Louis refused to sacrifice the non-juring priests or to authorize the establishment of a military camp of fédérés. On 12 June 1792, a letter from Jean-Marie Roland, vicomte de la Platière, Louis' Minister of the Interior, urged the King to yield on these two points, stating that his refusal would provoke the fall of the throne and a massacre of the aristocrats. The next day, the King dismissed Roland, along with Étienne Clavière, his Minister of Finance, and General Servan. On 15 June, General Dumouriez's reception by the Assembly was hostile enough to convince him that he would be arraigned. Since the King insisted on approving only the decree disbanding his guard, Dumouriez resigned and left to rejoin the Army of the North. The Feuillants returned to power in a new ministry.[9]

On 18 June, Lafayette, judging that the moment had come, called on the Assembly to destroy the democratic movement, declaring: "[The] Constitution of France [is] threatened by seditious groups within the country as well as by its enemies abroad." The King's use of the royal veto, his dismissal of the Girondin ministers, and the formation of a Feuillant ministry all served to show that he and the generals were attempting to enforce the political program advocated by the followers of Lafayette and Alexandre-Théodore-Victor, comte de Lameth. They were seeking to get rid of the Jacobin threat, revise the Constitution so as to reinforce royal authority, and bring the war to an end by making a deal with the enemy.[10]

Journée du 20 juin

Faced with the threat of a coup from either the royal family or the Feuillants, the Girondins tried to make use of the popular dynamism evident in sections of Paris. The Parisian mayor, Pétion, was sympathetic to their cause and helped the Girondins in these attempts.[11]

The anniversary of the Tennis Court Oath on 20 June was approaching. Sergent and Panis, the administrators of police sent out by Pétion, reached the Faubourg Saint-Antoine at about 8 o'clock. They urged the people to lay down their weapons, telling them it was illegal to present a petition in arms. The people refused to abandon their arms and said they did not intend to attack the Assembly or the King. They said they had two objectives: to form a procession for the twenty legal petitioners who wished to present a petition to the Assembly and the King, and to celebrate the anniversary of the Tennis Court Oath by planting a maypole in military fashion.[12]

By five o'clock in the morning on 20 June, groups had formed in the Faubourgs Saint-Antoine and Saint-Marcel, consisting of National Guardsmen, pikemen, gunners with their cannon, men armed with sabers or clubs, women, and children. Other armed petitioners had already appeared before the National Assembly. To prove to the city officials that they had no desire to riot, they invited the officials to join the procession and march along with them.[13]

The Legislative Assembly met about noon on the 20th, but did not turn its attention first to the threatened uprising. After some other business had been discussed, the president announced that the directory of the department wished to be admitted. The directory had shown great interest in trying to prevent the procession and had been in session since four o'clock in the morning.[14]

Pierre Louis Roederer, the procureur of the Paris department, brought the news about the mass protest to the Assembly. However, in the meantime, the crowd had reached the doors of the Assembly hall, the Salle du Manège. Their leaders asked permission to enter and present a petition. A violent debate arose between the Right, who were unwilling to admit the armed petitioners, and the Left, who, on the grounds of custom, wished to receive them. Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud argued that the Assembly would violate every principle by admitting armed bands; however, he admitted that it was impossible to deny a request in this case that had been granted in so many others. A majority of the representatives agreed that the petitioners should be allowed in. However, the crowd had already thronged the passages when the Assembly decided to admit them. The deputation was introduced.[15]

The deputation's spokesman, Sulpice Huguenin, expressed himself in threatening language. He said that the people were agitated; that they were ready to make use of the means stated in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen to resist oppression; that the dissenting members of the assembly, if there were any, wanted to destroy liberty and go to Koblenz. Then, returning to the true object of the petition, he added: "The executive power is not in union with you; we require no other proof of it than the dismissal of the patriot ministers. It is thus, then, that the happiness of a free nation shall depend on the caprice of a king! But should this king have any other will than that of the law? The people will have it so, and the life of the people is as valuable as that of crowned despots. That life is the genealogical tree of the nation, and the feeble reed must bend before this sturdy oak! We complain, gentlemen, of the inactivity of our armies; we require you to learn the cause of this; if it springs from the executive power, let that power be destroyed!"[15]

The Assembly answered that it would take the petitioners' request into consideration; it then urged them to respect the law and the legal authorities, and allowed them to march before the Assembly. Led by General Antoine Joseph Santerre, thirty thousand people, waving revolutionary banners and symbols, sang, as they traversed the hall, the famous chorus, Ça ira, and cried: "Vive la nation!" "Vivent les sans-culottes!" "À bas le veto!" On leaving the Assembly, the group proceeded to the King's chateau in the Tuileries Palace, led by the petitioners.[16]

The outer doors were opened at the King's command, and the crowd rushed in. They ascended to the apartments, and while they were forcing the doors open with hatchets, the King ordered them to be opened, and appeared before the crowd, accompanied by a few persons. Louis XVI was placed in the recess of a window. Surrounded by National Guardsmen, who formed a barrier against the mob, and seated on a chair placed on a table, Louis remained calm and firm.[16]

The crowd urged Louis to approve the decrees he had rejected. Louis responded: "This is neither the method nor the moment to obtain it of me." Attempting to mollify the mob, he placed on his head a red cap presented to him on the top of a pike. The crowd viewed this as a sign of humility. He then drank a glass of wine given to him by a half-drunken workman, and received strong applause.[17]

Meanwhile, Assembly members Vergniaud and Maximin Isnard, along with a few deputies of the Gironde, had moved forward to protect the King and attempt to calm the mob. The Assembly, which had just met, convened again quickly, terrified at this outbreak, and dispatched several successive delegations to try to protect Louis XVI. Eventually the mayor himself, Pétion, arrived; he mounted a chair, harangued the people, and urged them to withdraw quietly. The people obeyed. Thus, these singular insurgents, whose only aim was to obtain decrees and ministers, retired without achieving their mission.[17]

Aftermath

The demonstrators of 20 June did not obtain the immediate successes they had hoped for. The day's events were disowned by the Left of the Legislature, by the future Girondins, and by the Jacobins. Louis XVI, who had promised nothing, did not withdraw his veto. The petitioners thought they had converted him to the Revolution; instead, they found him to be embittered, humiliated, and irremediably hostile.[18]

Europe saw the King insulted and treated as a prisoner. In parts of France, royalism regained popularity. A large number of departmental administrations protested against the insult offered to the majesty of royalty. Lafayette, leaving his army, visited the Assembly on 28 June, demanding in the name of his soldiers that the Assembly take action against the protesters, and "destroy a sect capable of infringing the national sovereignty." But on 2 July came the news that the Army of the North was in retreat and was falling back on Lille and Valenciennes. This made all the distrust and anxiety of the petitioners of 20 June seem justified.[19]

In the Assembly on 3 July, Vergniaud denounced all the "treasonous" acts of Louis XVI. He recalled the royal veto, the disturbances it had caused in the provinces, and the deliberate inaction of the generals who had opened the way to invasion. Furthermore, he suggested to the Assembly – though by implication rather than directly – that Louis XVI might qualify under the Constitution as being "considered to have abdicated his royal office." Thus, he put the idea of deposing the King into the public's minds. His speech, which made an enormous impression, was circulated by the Assembly through all the departments of France.[20]

It was now certain that there would be a more violent sequel to the demonstration of 20 June 1792. Jacobin Jacques Nicolas Billaud-Varenne outlined a program for the next insurrection: exile the King, dismiss the generals, elect a National Convention, transfer the royal veto to the people, deport all public enemies, and exempt the poor from taxation. This program was repeated, almost unchanged, in a strongly worded manifesto drawn up by Robespierre, and proclaimed by a federal orator before the House. The real question was how it would be carried out.[21]

The answer came on 10 August 1792 with the storming of the Tuileries Palace.

See also

References

- Soboul 1974, p. 241.

- Lefebvre 1962, p. 225.

- Lefebvre 1962, p. 222.

- Lefebvre 1962, p. 223.

- Vovelle 1984, p. 224.

- Pfeiffer 1913, p. 13.

- Pfeiffer 1913, p. 14.

- Pfeiffer 1913, p. 16.

- Lefebvre 1962, p. 227.

- Soboul 1974, p. 245.

- Vovelle 1984, p. 226.

- Pfeiffer 1913, p. 56.

- Taine 2011, p. 298.

- Pfeiffer 1913, p. 63.

- Mignet 1824, p. 156.

- Mignet 1824, p. 157.

- Mignet 1824, p. 158.

- Aulard 1910, p. 365.

- Aulard 1910, p. 366.

- Mathiez 1929, p. 155.

- Thompson 1959, p. 281.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Demonstration of 20 of June 1792. |

- Aulard, François-Alphonse (1910). The French Revolution, a Political History, 1789-1804, in 4 vols. Vol. I. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hampson, Norman (1988). A Social History of the French Revolution. Routledge: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-710-06525-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lefebvre, Georges (1962). The French Revolution: from its Origins to 1793. vol. I. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08599-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madelin, Louis (1926). The French Revolution. London: William Heinemann Ltd.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mathiez, Albert (1929). The French Revolution. New York: Alfred a Knopf.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mignet, François (1824). History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814. Project Gutenberg EBook.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pfeiffer, L. B. (1913). The Uprising of June 20, 1792. Lincoln: New Era Printing Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rude, George (1972). The Crowd in the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Soboul, Albert (1974). The French Revolution: 1787-1799. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-47392-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taine, Hippolyte (2011). The Origins of Contemporary France, Volume 3. Project Gutenberg EBook.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, J. M. (1959). The French Revolution. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vovelle, Michel (1984). The Fall of the French monarchy 1787-1792. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28916-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)