Difenoxin

Difenoxin (Motofen, R-15403) is an opioid drug used, often in combination with atropine, to treat diarrhea.[1] It is the principal metabolite of diphenoxylate.[2][3]:558

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Difenoxin, Motofen |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

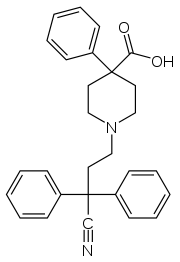

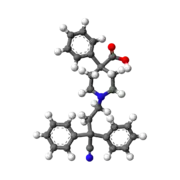

| Formula | C28H28N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 424.544 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

It was first approved in the US in 1978[4] and in 1980 in the former West Germany.[5]:485

Difenoxin crosses the blood brain barrier and induces some euphoria; it is often sold with or administered with atropine to reduce the potential for abuse and overdose.[1]

Available forms

The abuse-deterring effects of atropine when used as an adulterant are reasonably effective in reducing the combination's potential for recreational use. It combines the mechanisms of naloxone and paracetamol (the two more commonly used abuse-deterring agents) by increasing the likelihood of the overdose resulting in harmful and/or fatal sequelae (as does paracetamol), in addition to reliably producing unpleasant side-effects which "spoil" the opioid euphoria and discourage abusers from overdosing again following their initial experience (as does naloxone). This does not deter the use of single doses of difenoxin to potentiate another opiate, the anticholingeric activity of a single tablet is actually likely to increase the pleasurable effects of opioid use in a manner similar to combining one or more opioids with orphenadrine.

Side effects

At high doses there are strong CNS effects and the atropine at such high doses causes typical anticholinergic side effects, such as anxiety, dysphoria, and delirium. Excessive use or overdose causes constipation and can promote development of megacolon as well as classic symptoms of overdose including potentially lethal respiratory depression.[1] In the 1990s its use in children was restricted in many countries due to the CNS side effects, which included anorexia, nausea and vomiting, headache, drowsiness, confusion, insomnia, dizziness, restlessness, euphoria and depression.[2]

Mechanism of action

Difenoxin has a high peripheral/central actions ratio, working primarily on various opioid receptors in the intestines.[6] Although it is capable of producing significant central effects at high doses, doses within the normal therapeutic range generally do not notably impair cognition or proprioception, resulting in therapeutic activity roughly equatable to that of loperamide (Imodium). Increased dosages result in more prominent central opioid effects (and anticholingeric effects when the formulation also contains a tropane alkaloid). It therefore offers limited advantages over more potent anti-diarrheal opioid options (ex. morphine) when treating intractable cases of diarrhea which fail to respond to normal or moderately increased difenoxin doses, and may in fact be harmful in such circumstances if the formulation used also contains atropine or hyoscyamine.

Legal status

Difenoxin is a Schedule I drug by itself in the US; the combination with atropine is in the less-restrictive category Schedule IV on account of the adulterant (the practice of making opioids more easily available by including an abuse-deterring adulterating agent is standard practice in the United States). Pure difenoxin, in Schedule I, has a quota of 50 grammes, and an ACSCN of 9168. The combination of difenoxin and atropine, in Schedule IV, has the DEA ACSCN of 9167 and being in Schedule IV is not assigned an aggregate annual manufacturing quota.[7]

References

- Scarlett Y (January 2004). "Medical management of fecal incontinence". Gastroenterology. 126 (1 Suppl 1): S55-63. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.007. PMID 14978639.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2005). "Consolidated List of Products Whose Consumption and/or Sale Have Been Banned, Withdrawn, Severely Restricted or not Approved by Governments" (PDF). New York: United Nations. p. 109. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- Katzung BG, Masters SB, Trevor AJ (2012). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 9780071764025.

- "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- Sittig M (1988). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia. 1–2 (2nd ed.). William Andrew Publishing/Noyes. ISBN 9780815511441.

- Jackson LS, Stafford JE (November 1987). "The evaluation and application of a radioimmunoassay for the measurement of diphenoxylic acid, the major metabolite of diphenoxylate hydrochloride (Lomotil), in human plasma". Journal of Pharmacological Methods. 18 (3): 189–97. doi:10.1016/0160-5402(87)90069-6. PMID 3682841.

- "Lists of Scheduling Actions, Controlled Substances, Regulated Chemicals (Orange Book)" (PDF). DEA. May 2016.