Dolichopodidae

Dolichopodidae, the long-legged flies, are a large, cosmopolitan family of true flies with more than 7,000 described species in about 230 genera. The genus Dolichopus is the most speciose, with some 600 species.

| Dolichopodidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chrysosoma sp. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Infraorder: | Asilomorpha |

| Superfamily: | Empidoidea |

| Family: | Dolichopodidae Latreille, 1809 |

| Subfamilies | |

|

sensu stricto:

sensu lato: | |

| Diversity | |

| About 230 genera, more than 7,000 species | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dolichopidae | |

Dolichopodidae generally are small flies with large, prominent eyes and a metallic cast to their appearance, though there is considerable variation among the species. Most have long legs, though some do not. In many species the males have unusually large genitalia which are taxonomically useful in identifying species. Most adults are predatory on other small animals, though some may scavenge or act as kleptoparasites of spiders or other predators.

An expanded concept of the family (Dolichopodidae sensu lato) includes the subfamilies Parathalassiinae and Microphorinae. The latter of these was formerly placed in the Empididae, and was at one time considered a separate family (Microphoridae).[5] However, some authors propose instead that Dolichopodidae s.l. should be known as the epifamily Dolichopodoidae, containing Dolichopodidae, Microphoridae (restored as a family) and the subfamily Parathalassiinae.[6]

.jpg.webp)

Description

For clarification of technical terms see Morphology of Diptera

Dolichopodidae are a family of flies ranging in size from minute to medium-sized (1mm to 9mm). They have characteristically long and slender legs, though their leg length is not as striking as in families such as the Tipulidae. Their posture often is stilt-like standing high on their legs, with the body almost erect. In colour most species have a green-to-blue metallic lustre, but various other species are dull yellow, brown or black.

The frons in both sexes is broad. The eyes are separated on the frons of males, except in some species of Diaphorus and Chrysotus in which eyes touch above the antennal insertion.[7] On the heads of most species the ocellar bristles and outer vertical bristles are well developed. The face of some species is entire; in others it is divided into two sections: the epistoma and the clypeus. The largest antennal segment is the third; in most species it bears a long arista, which is apical in some species, dorsal in others. In most species the mouthparts are short and have a wide aperture as an adaptation for sucking small prey.

The legs are gracile and the tibiae usually bear long bristles. In some genera the legs are raptorial. In some species the tibiae of the males have modifications.

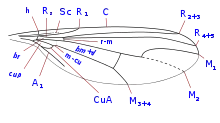

The wings of most species are clear or tinged, but some species have wings that are patterned in strong colours or with distinct spots. There are three radial veins (R1, R2+3, R4+5). The medial vein M1+2 is simple or rarely furcate, as in the genus Sciapus. The anterior cross-vein is in the basal part of the wing. The posterior basal wing cell and the discoidal wing cell are always fused. The anal cell of the wing is always small. There are two veins branching from cross-vein DM-Cu in the direction of the wing margin; the upper one in some species curves strongly or forks into M1 and M2. R4+5 are simple, and costa ends near or at M1/M1+2, or continues along the wing margin. The point of origin of Rs is at or very close to h.[8]

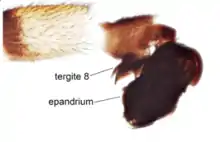

The abdomen is elongate-conical or flat. The genitalia of the male often are free and borne on a petiole, with tergite 8 being asymmetrical, lying on the left side of the epandrium. They are also rotated dextrally between 90° and 180°, including segment 8 and sometimes segment 7, which makes them distinguishable from the family Hybotidae.[8] Males of most species have well developed gonopods of two or three lobes on the distal margin of the epandrium. The gonopods may fuse with the epandrium in genera such as Hydrophorus, Thrypticus and Argyra, or there may be a suture, as in the genera Porphyrops, Xiphandrium and Rhaphium. In some genera, such as Hypophyllus and Tachytrechus, the surstyli are well-developed as secondary outgrowths of the epandrium. In genera such as Tachytrechus, there are two pairs of surstyli—one proximal and one distal. The hypandrium in most species is a small sclerite, which may be asymmetrical as in the genera Porphyrops and Tachytrechus. Males of many species have highly developed cerci. Development of the phallus varies considerably between genera.

.jpg.webp)

Biology

Adults of the Dolichopodidae live largely in grassy places and shrubbery. The flies occur in a wide range of habitats, near water or in meadows, woodland edges and in gardens. Some groups are confined to wet places including sands on the banks of water bodies; examples include genera such as Porphyrops, Tachytrechus, Campsicnemus, and Teuchophorus. No truly aquatic species have been described, but many are semi-aquatic and live in or near water margins. A small number of species develop on the shores of saline inland bodies of water or the intertidal zone of seashores. An example of a species that develop close to water is P. nobilitatus, they can be found congregating around lakes and ponds. Other groups are found on trunks of trees damaged by bark beetles. Adults often are seen in a characteristic predatory posture standing high on their legs on the ground or on vegetation, tree trunks or rocks, and some species walk about on the surface of still water.

The adults are predators, feeding on small invertebrates including Collembola, aphids, and the larvae of Oligochaeta. Species of the genus Dolichopus commonly prey on the larvae of mosquitoes.

The larvae occupy a wide range of habitats. Many are predators of small invertebrates and generally live in moist environments such as soil, moist sand, or rotting organic matter. Genera such as Medetera live as predators under tree bark or in the tunnels of bark beetles. Larvae of the genus Thrypticus are unusual among Dolichopodidae, in that they are phytophagous and live in the stems of reeds and other monocots near water.

Behaviour

Many studies have shown that Dolichopodidae give visual, rather than chemical or other signals during courtship.[9] The males of many species exhibit elaborate secondary sexual characters assumed to aid in species recognition during courtship. These characters include flaglike flattening of the arista and tarsi, strongly modified setae and projections of the tarsi, the prolongation and deformation of podomeres, orientated silvery pruinosity, and maculation or modification of the wings.

Evolution and systematics

Dolichopodids are well represented in amber deposits throughout the world and the group has clearly been well distributed since the Cretaceous at the latest. Together with the Empididae they are the most advanced members of the Empidoidea. They represent the bulk of Empidoidea diversity, and include more than two-thirds of the known species in their superfamily.

Taxonomic interrelationships within the Dolichopodidae, and their delimitation from the Empididae, are not yet satisfactorily resolved. It is likely that many of the subfamilies currently within the Dolichopodidae will undergo drastic revision.[10]

Based on the most recent phylogenetic studies, the relationship between Dolichopodidae and other members of Empidoidea is as follows. The placement of Dolichopodidae is emphasized in bold formatting.

| Atelestidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Identification

- Negrobov, P. and Shtakel'berg, A. A. Family Dolichopodidae in Bei-Bienko, G. Ya, 1988 Keys to the insects of the European Part of the USSR Volume 5 (Diptera) Part 2 English edition. Keys to Palaearctic species but now needs revision.

- Parent, O., 1938 Diptères Dolichopodidae. Paris: Éditions Faune de France 35. virtuelle numérique

Species lists

See also

- List of dolichopodid genera

Sciapus sp.

Sciapus sp.

Footnotes

- Yang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L. (2006). World Catalog of Dolichopodidae (Insecta: Diptera). Beijing: China Agricultural University Press. pp. 1–704. ISBN 9787811171020.

- Grootaert, P; Meuffels, H.J.G. (1997). "Dolichopodidae (Diptera) from Papua New Guinea. XV. Scepastopyga gen. nov. and the establishment of a new subfamily, the Achalcinae". J. Nat. Hist. 31 (10): 1587–1600. doi:10.1080/00222939700770841.

- Bickel, D. J. (1987). "Babindellinae, a new subfamily of Dolichopodidae (Diptera) from Australia, with a discussion of symmetry in the dipteran male postabdomen". Entomologica Scandinavica. 18: 97–103. doi:10.1163/187631287X00061. ISSN 1399-560X.

- Grichanov, I.Ya. (2018). "A new subfamily of Dolichopodidae (Diptera) for Tenuopus Curran, 1924 with description of new species from Tropical Africa" (PDF). Far Eastern Entomologist. 365: 1–25. doi:10.25221/fee.365.1.

- Sinclair, Bradley J.; Cumming, Jeffrey M. (2006). The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) (PDF). Zootaxa. 1180. pp. 1–172. ISBN 978-1-877407-80-2. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- Grichanov, I. Ya. (2011). "An illustrated synopsis and keys to afrotropical genera of the epifamily Dolichopodoidae (Diptera: Empidoidea)". Priamus Supplement (24): 1–98.

- Robinson, H. and JR Vockeroth. Dolichopodidae. JF McAlpine Manual of Nearctic Diptera vol. 1 1981. 625-639. Research Branch Agriculture Canada Monograph 27 Ottawa.

- Wahlberg, Emma; Johanson, Kjell Arne (2018). "Molecular phylogenetics reveals novel relationships within Empidoidea (Diptera)". Systematic Entomology. 43 (4): 619–636. doi:10.1111/syen.12297. ISSN 1365-3113.

- E.g. Zimmer et al. (2003), Irwin (2007), Vikhrev (2007)

- Sinclair and Cumming (2006), Moulton and Wiegmann (2007)

References

- Moulton, J.K.; Wiegmann, B.M. (2007). "The phylogenetic relationships of flies in the superfamily Empidoidea (Insecta: Diptera)". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 43 (3): 701–713. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.029. PMID 17468014.

- Irwin, Tony (2007): Neurigona courtship. Version of 2007-JUN-18. Retrieved 2008-JUL-30.

- Sinclair, B.J.; Cumming, J.M. (2006). "The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera)" (PDF). Zootaxa. 1180: 1–172. ISBN 1-877407-80-1.

- Vikhrev, Nikita (2007): Observations on Medetera jacula (Fallén, 1823). Version of 2007-JAN-22. Retrieved 2008-JUL-30.

- Wahlberg, E.; Johanson, K.A. (2018). "Molecular phylogenetics reveals novel relationships within Empidoidea (Diptera)". Systematic Entomology. 43 (4): 619–636. doi:10.1111/syen.12297.

- Zimmer, Martin; Diestelhorst, Olaf; Lunau, Klaus (2003). "Courtship in long-legged flies (Diptera: Dolichopodidae): function and evolution of signals" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology. 14 (4): 526–530. doi:10.1093/beheco/arg028.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dolichopodidae. |

- Bug Guide images

- Diptera.info images

- Family Dolichopodidae at EOL images

- Dolichopodidae in Italian

- Igor Grichanov Dolichopodidae home page

- Family description

- Family description

- University of Lille Multi-imaged site. Whole specimens and parts.

- Video of sciapodine of Texas

.tif.jpg.webp)