Dollosuchus

Dollosuchus is an extinct tomistomine. It is a basal form possibly related to Kentisuchus, according to several phylogenetic analyses that have been conducted in recent years,[1][2][3] and is the oldest known tomistomine to date. Fossils have been found from Belgium and the United Kingdom.[4] It had large supratemporal fenestrae in relation to its orbits, similar to Kentisuchus and Thecachampsa.[5]

| Dollosuchus Temporal range: Early Eocene | |

|---|---|

| |

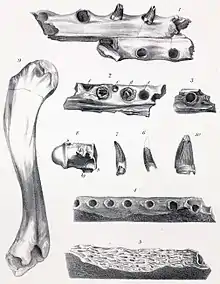

| Fossils referred to Gavialis dixoni by Richard Owen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Gavialidae |

| Subfamily: | Tomistominae |

| Genus: | †Dollosuchus Owen, 1850 |

| Type species | |

| †Dollosuchus dixoni Owen, 1850 | |

Dollosuchus was originally described on the basis of numerous mandibular fragments found from the Early to Middle Eocene Bracklesham Beds in the United Kingdom. The material cannot be distinguished from other related longirostrine, or long-snouted, crocodilians. A nearly complete skeleton from Belgium (IRScNB 482) described by Swinton, and referred to Dollosuchus, formed the basis of the new taxon Dollosuchoides densmorei.[3] The skeleton itself is open to the public eye at The World of Kina.

Species

The type species of Dollosuchus is D. dixoni. Many other species that once belonged to other genera have been proposed as members of the genus, but little work has been published to support these claims. Charactosuchus kugleri, another Eocene crocodilian, has been suggested to be synonymous with Dollosuchus,[6] but this is no longer likely because C. kugleri is now thought to be a member of the family Crocodylidae, and thus closer related to modern crocodiles than to gharials. It has been suggested that Kentisuchus spenceri, Megadontosuchus arduini, and Dollosuchus dixoni are cogeneric. If this is the case, the genus name Dollosuchus would be adopted for all three species, as the name has seniority over the other two.[7][8]

References

- Jouve, S. (2004). Etude des crocodyliformes fini Crétace−Paléogène du Bassin de Oulad Abdoun (Maroc) et comparaison avec les faunes africaines contemporaines: systématique, phylogénie et paléobiogéographie. Ph.D. thesis. 652 pp. Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris, Paris.

- Delfino, M.; Piras, P.; Smith, T. (2005). "Anatomy and phylogeny of the gavialoid crocodylian Eosuchus lerichei from the Paleocene of Europe". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 50: 565–580.

- Brochu, C. A. (2007). "Systematics and taxonomy of Eocene tomistomine crocodylians from Britain and Northern Europe". Palaeontology. 50 (4): 917–928. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00679.x.

- Swinton, W. E. (1937). "The crocodile of Maransart (Dollosuchus dixoni [Owen])". Mémoires du Musée d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique. 80: 1–44.

- Piras, P.; Delfino, M.; Del Favero, L.; Kotsakis, T. (2007). "Phylogenetic position of the crocodylian Megadontosuchus arduini and tomistomine palaeobiogeography". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 52 (2): 315–328.

- Domning, D. P.; Clark, J. M. (1993). "Jamaican Tertiary marine Vertebrata. In: R.M. Wright and E. Robinson (eds.)". Biostratigraphy of Jamaica. Geological Society of America Memoir. 182: 413–415. doi:10.1130/mem182-p413.

- Brochu, C. A. (1997). Phylogenetic Systematics and Taxonomy of Crocodylia. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. 467 pp. University of Texas, Austin

- Brochu, C. A. (2001). Congruence between physiology, phylogenetics, and the fossil record on crocodylian historical biogeography. In: G. Grigg, F. Seebacher, and C.E. Franklin (eds.), Crocodilian Biology and Evolution, 9–28. Surrey Beatty and Sons, Sydney

External links

- Dollosuchus in the Paleobiology Database