Tomistominae

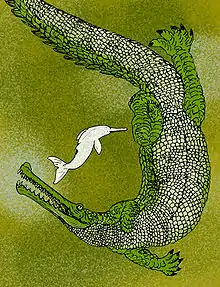

Tomistominae is a subfamily of crocodylians that includes one living species, the false gharial. Many more extinct species are known, extending the range of the subfamily back to the Eocene epoch. In contrast to the false gharial, which is a freshwater species that lives only in southeast Asia, extinct tomistomines had a global distribution and lived in estuaries and along coastlines.

| Tomistominae | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| False gharial, Tomistoma schlegelii | |

| Scientific classification (disputed) | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Superfamily: | Gavialoidea |

| Family: | Gavialidae |

| Subfamily: | Tomistominae Kälin, 1955 |

| Genera | |

The classification of tomistomines among Crocodylia has been in flux; while traditionally thought to be within Crocodyloidea, molecular evidence indicates that they are more closely related to true gharials as members of Gavialoidea.[1][2]

Description

Tomistomines have narrow or longirostine snouts like gharials. The living false gharial lives in fresh water and uses its long snout and sharp teeth to catch fish, although true gharials are more adapted toward piscivory, or fish-eating. Despite the similarity with gharials, the shapes of bones in tomistomine skulls link them with crocodiles. For example, both tomistomines and crocodiles have thin postorbital bars behind the eye sockets and a large socket for the fifth maxillary tooth. The splenial bone of the lower jaw is long and slender, forming a distinctive "V" shape not seen in gharials.

Evolutionary history

Tomistomines first appeared in the Eocene in Europe and North Africa. The oldest known tomistomine is Kentisuchus spenceri from England, although a possible tomistomine fossil from the Paleocene of Spain is even older.[3] Other early tomistomines include Maroccosuchus zennaroi from Morocco and Dollosuchus dixoni from Belgium. These early tomistomines inhabited the Tethys Ocean, which covered much of Europe and North Africa during the Paleogene. Several early tomistomines are found in coastal marine deposits, suggesting that they lived along the shoreline or in estuaries. Extinct gavialoids are also thought to have been coastal animals. The marine lifestyles of these early forms likely allowed tomistomines to spread around the Tethys, forming a northern population in Europe and a southern in North Africa.[3]

Later in the Eocene and Oligocene, tomistomines spread across Asia. The middle Eocene species Ferganosuchus planus and Dollosuchus zajsanicus are known from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Tomistomines reached China and Taiwan with the late Eocene species Maomingosuchus petrolica and the Miocene species Penghusuchus pani.[4] One species, "Tomistoma" tandoni, lived in India during the middle Eocene. During this time, the Indian subcontinent was separated from mainland Asia, creating a barrier to species that could not tolerate salt water. The Obik Sea, which separated Europe from Asia, also impeded travel. Tomistomines were able to cross these areas, indicating that they had tolerance to salt water.[3]

Tomistomines crossed the Atlantic Ocean and spread into the Americas in the Oligocene, Miocene, and Pliocene. The earliest known neotropical tomistomine is Charactosuchus kuleri from Jamaica. A close relationship has been proposed between C. kuleri and D. zajsanicus from Belgium, suggesting that tomistomines migrated from Europe to the Americas through the De Geer land bridge connecting Norway to Greenland and the North American mainland or the Thule land bridge connecting Scotland, Iceland, Greenland, and the North American mainland. The genus Thecachampsa was present along the eastern coast of North America during the Oligocene, Miocene, and Pliocene.[3]

Tomistomines disappeared from Europe during the Oligocene but returned by the end of the epoch. They diversified and became common in the middle Miocene. One tomistomine, Tomistoma coppensi, is known from the late Miocene of Uganda. The appearance of tomistomines in central Africa is unusual because there is little evidence of late Miocene species in North Africa, an area where they must have traveled through from Europe.[3]

Tomistomines may have traveled from Africa into Asia when Arabia collided with the Eurasian continent in the Early Miocene. However, Asian Miocene tomistomines may also have descended from the Eocene tomistomines that were already present in eastern Asia. Tomistomines spread throughout the Indian subcontinent during this time. One species, Rhamphosuchus crassidens, was one of the largest crocodilians that ever lived, growing to an estimated 8 to 11 metres (26 to 36 ft). New species such as Toyotamaphimeia machikanensis were present in Japan in the Pleistocene. In southeast Asia however, there is little fossil evidence of the tomistomines that preceded the false gharial. Therefore, its relation with extinct species is unclear.[3]

Phylogeny

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The false gharial Tomistoma is similar to the true gharial Gavialis in that it is longirostrine, meaning that it has a long, narrow snout. While crocodiles are also longirostrine, their snouts are not as narrow as those of Tomistoma and Gavialis. Details of the morphology of Tomistoma and Gavialis suggest that the two are only distantly related and that long snouts evolved independently in each lineage as a result of convergent evolution. Morphologically, tomistomines seem to be more closely related to crocodylids, having shared a more recent common ancestor with crocodiles than with the gharial. Under this phylogeny, gharials split with the common ancestors of tomistomines, crocodiles, and alligators over 66 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous.[5] Below is a cladogram from Piras et al. (2007) placing tomistomines within Crocodyloidea:[3]

| Crocodylia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Recent molecular analyses of crocodylians find a closer relationship between Tomistoma and Gavialis. According to this phylogeny, the two forms are sister taxa, more closely related to each other than either is to any other living crocodylian.[2] If they are sister taxa, the divergence of the two forms is thought to have occurred in the Eocene or mid-Miocene.[5] If Tomistoma and Gavialis are considered to be closely related, the morphological similarities between Tomistoma and crocodiles must be convergent. In this case, convergence leads to a problem known as long branch attraction, where similar but independently evolved features in Tomistoma and crocodiles misleadingly imply that these two highly derived groups are closely related. In effect, these shared characters mask the closer relationship between Tomistoma and Gavialis.[6]

Long branch attraction can be resolved if differences are observed between ancestral members of each group. If the two groups were closely related, early members should have primitive traits from a common ancestor and should lack the derived traits that cause long branch attraction. Tomistomine fossils do not resolve long branch attraction when their characters are added to phylogenetic analyses, so conflict still exists between morphological and molecular phylogenies.[6]

Some studies have combined morphological and molecular characters in their analyses. Analyses that include morphological characters but still rely heavily on the sequences of DNA find a close relation between Tomistoma and Gavialis. Analyses that use more characters from bones and fossils uphold the close relationship of Tomistoma with crocodiles.[6]

Relations within Tomistominae

Below is a cladogram from Shan et al. (2009):[4]

| Crocodyloidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The cladogram below follows Christopher A. Brochu and Glenn W. Storrs (2012) analysis.[7]

| Crocodyloidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Gatesy, Jorge; Amato, G.; Norell, M.; DeSalle, R.; Hayashi, C. (2003). "Combined support for wholesale taxic atavism in gavialine crocodylians" (PDF). Systematic Biology. 52 (3): 403–422. doi:10.1080/10635150309329. PMID 12775528.

- Willis, R. E.; McAliley, L. R.; Neeley, E. D.; Densmore Ld, L. D. (June 2007). "Evidence for placing the false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii) into the family Gavialidae: Inferences from nuclear gene sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 43 (3): 787–794. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.005. PMID 17433721.

- Piras, P.; Delfino, M.; Del Favero, L.; Kotsakis, T. (2007). "Phylogenetic position of the crocodylian Megadontosuchus arduini and tomistomine palaeobiogeography" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 52 (2): 315–328.

- Shan, Hsi-yin; Wu, Xiao-chun; Cheng, Yen-nien; Sato, Tamaki (2009). "A new tomistomine (Crocodylia) from the Miocene of Taiwan". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 46 (7): 529–555. Bibcode:2009CaJES..46..529S. doi:10.1139/E09-036.

- Piras, P.; Colangelo, P.; Adams, D.C.; Buscalioni, A.; Cubo, J.; Kotsakis, T.; Meloro, C.; Raia, P. (2010). "The Gavialis-Tomistoma debate: the contribution of skull ontogenetic allometry and growth trajectories to the study of crocodylian relationships". Evolution & Development. 12 (6): 568–579. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2010.00442.x. PMID 21040423. S2CID 8231693.

- Brochu, C. A. (2003). "Phylogenetic approaches toward crocodylian history" (PDF). Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 31 (31): 357–97. Bibcode:2003AREPS..31..357B. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.31.100901.141308.

- Brochu, C. A.; Storrs, G. W. (2012). "A giant crocodile from the Plio-Pleistocene of Kenya, the phylogenetic relationships of Neogene African crocodylines, and the antiquity of Crocodylus in Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (3): 587. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.652324. S2CID 85103427.