Dragoon Springs, Arizona

Dragoon Springs is an historic site in what is now Cochise County, Arizona, at an elevation of 4,925 feet (1,501 m). The name comes from a nearby natural spring, Dragoon Spring, to the south in the Dragoon Mountains at 5,148 feet (1,569 m) (31°59′5″N 110°0′56″W).[1] The name originates from the 3rd U.S. Cavalry Dragoons who battled the Chiricahua, including Cochise, during the Apache Wars. The Dragoons established posts around 1856 after the Gadsden Purchase made the area a U.S. territory.

Dragoon Springs | |

|---|---|

Dragoon Springs Location in Arizona | |

| Coordinates: 31°59′51″N 110°01′20″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Cochise County |

| Elevation | 4,925 ft (1,501 m) |

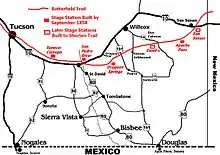

Dragoon Spring was a watering place on the Southern Emigrant Trail in territory which eventually joined the United States in the Gadsden Purchase, becoming part of the New Mexico Territory. Following the purchase, Dragoon Spring was used as a watering place by the San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line, commonly called the "Jackass Mail", starting in July 1857. After Butterfield started service in September 1858, the Jackass Mail was still operating using Butterfield's improved trail.[2]

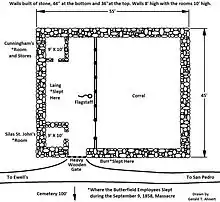

Dragoon Springs Stage Station was the second of the two stone fortified stations constructed in Arizona and was the last going west on the 2,700 mile trail from Tipton, Missouri, to San Francisco, California. A six-year mail contract, No. 12,578, was awarded to John Butterfield to start on September 1858 and end on September 15, 1864.[3] [4] [5] This station was built in August and early September 1858 by Butterfield's Overland Mail Company to house employees and livestock. The construction of the station was supervised by Butterfield Division Superintendent William Buckley of Watertown, New York.[6]

The station was used by the Butterfield Overland Mail from September 1858 to March 1861 and by other stage lines from 1865 to about 1880. An order dated March 2, 1861, was sent to the Overland Mail Company to transfer the contract to the Central Overland Trail, because of the start of the Civil War. The present marker at the station states that one of the reasons was because of competition from the Pony Express, but the Pony Express never existed in Arizona and was not in competition with any stage line.

The earliest stage line to use the station, when a through service returned to the Southern Overland Trail, was Tomlinson & Co.[7]

During the American Civil War, it was the site of the First Battle of Dragoon Springs and near to the site of the Second Battle of Dragoon Springs, fought between Apache warriors and Confederate soldiers.

The Six Graves at Dragoon Springs Stage Station

There are six graves that have been identified at the Dragoon Springs Stage Station. There are four rock cairns covering graves north of the gate to the entrance of the ruins of the stage station building. There are two to the west of the same building, consistent with historical accounts. Records indicate that seven individuals were killed at or near the station and they were buried in six graves, and when carefully assessing the evidence the identity of those buried in each set of graves is clear.

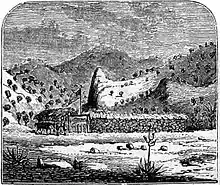

Two Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company Graves

The drawing by H. C. Grosvenor, made in 1860, shows the two graves of north the station gate. The photograph to the right was taken from the approximate position of Grosvenor when he made the drawing. In both the drawing and the photo, when a straight line is drawn starting at the top apex of the shark fin like mountain, to the station gate and through the center of the graves, the lines match exactly. Well, to some extent exactly because as any experienced surveyor knows, one can draw a straight line between any two points. In fact, these historical drawings are known to have been approximate and to have collapsed a wider view into a narrower drawing (Seymour 2019).

From the history book that contained the Grosvenor drawing was this:

“This station, or corral, is 85 miles east of Tucson. It is a rectangular enclosure, protected by a stone wall eight foot high. One third of the space is occupied by storehouses and the sleeping apartment of the station master. These structures are covered by thatched roofs. The mules are kept in the other part, ready for change on the arrival of the mail. A heavy wooden gate defends the entrance. The two graves in the foreground are mementos of a tragedy that occurred on the night of September 8, 1858. Rude wooden slabs at their head bear brief inscriptions. ...With little hope of living, St. John succeeded in writing an account of the murder in a small book, for the information of the mail party that was due the succeeding Monday."[8]

In the drawing it appears that the two graves are in line head to foot. They were staggered with a space between them and, at ground level, they are drawn from the perspective of the artist, and this latter point is important to remember.

The graves of Butterfield's Overland Mail Company employees are a result of a massacre that started a few minutes after midnight on September 9, 1858. Some of the station construction crew had just gone on to the San Pedro River to build a station. Left behind were Silas St. John, James Burr, William Cunningham, James Laing, and three Mexican laborers. One of the construction crew that had just left for the San Pedro River was Superintendent William Buckley. As one of those that was killed was his uncle, he wrote an account of the massacre for their hometown newspaper in Upstate New York.

”The last hope that there might be an error or falsehood in the first report of the massacre of our old fellow townsman, Mr. James Burr, and his companions, at Dragoon Springs has been dispelled by a letter from William Buckley, one of the superintendents of the overland mail company, to his father. The details of the horrid murder equal in atrocity anything we read in the annals of crime. Mr. B. writes from Tucson, seventy-five miles from Dragoon Springs, September 14, five days after the murder. We copy from his letter: Uncle James, Mr. St. John, Mr. Cunningham and Mr. Laing, together with three Mexicans in our employ, were stationed at that place, [Dragoon Springs.] Everything had gone on well. I had not learned of any trouble between the men. I had eight mules with quite a large amount of property at the place. The murder was committed by the three Mexicans. Mr. Laing is undoubtedly dead before this. Mr. St. John is wounded, but I think with good care he will recover. The murder was committed in order to steal the property, as I had quite a large amount there. Uncle James was lying outside the corral when he was found, which was on Sunday morning. The murder was committed on Wednesday night. He lay in his blankets, with his head on one side all broken in. He had been killed with a stone hammer, and from all appearances he was struck two blows. He undoubtedly died without a struggle, from his appearance and position when found. Mr. Colwell and another man I had sent up to Dragoon Springs arrived there Sunday morning. Soon after the stage came up with Lieutenant Mowry, Colonel Leach, and several other passengers. Immediately on their arrival they buried uncle James and attended to the wants of the wounded men. They had nothing to eat or drink from Wednesday night to Sunday morning, being unable to move from the corral. Everything was done for them that men could do."[9]

Silas St. John gave a personal account of the incident and described the circumstances for being discovered with two horrible wounds and having his arm amputated at the station.

”With Sunday morning came relief. Mr. Archibald, correspondent for the Memphis Avalanche, arrived from Tucson on his way to the Rio Grande. Seeing no flag flying and no one moving about the station, he halted a half mile distant, leaving his horse with his companion, and approached with his gun cocked. St. John could not respond to his halloas as his tongue and throat were disabled from thirst. Archibald at once started for the spring, a mile distant up the canyon. He had no sooner left than three wagons of the Leach road party approached from the East. They, too, seeing no life about the station, left the road and made a detour about half a mile to the south—fearing an ambuscade. Then they cautiously approached the corral on foot. In the party were Col. James B. Leach, Major N. H. Hutton and some other veterans, who quickly dressed St. John’s wounds, which were full of maggots. They buried the bodies of Hughes [Burr] and Cunningham in one grave. Laing still hung to life tenaciously although nothing could be done for him—he died on Monday. An express was started for Fort Buchanan by way of Tucson, as the direct route was not deemed safe for two men. They reached the fort on Wednesday following. The doctor, Asst. Surgeon B. J. D. Irwin, started at once with an escort and reached Dragoon on Friday morning—the ninth day after St. John was wounded. The arm was amputated at the socket. Six days afterward, St. John got into a wagon and rode to the fort; five days later he was able to walk about, and ten days thereafter, being twenty-one days from the operation, was able to mount a horse and ride to Tucson. A remarkable quick recovery from such severe wounds.”[10]

An article in The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 1858, titled “Amputation at the Shoulder-Joint, by B. J. D. Irwin, M. D., U. S. Army,”[11] gives a brief account of the massacre which corresponds to St. John's description. Irwin was the surgeon who operated on St. John.

”…The largest is a double grave in which rests together the remains of Wm. Cunningham, and James Hughes [Burr]. The single grave next south is that of James Laing. The two graves north of the double grave are those of a Cal. regiment which used the old station as a fort in 62-63. Those graves have each a rough stone inscribed with the names of the occupants. The double grave and the single one to the south of them are without markers. My good left arm was buried between those graves.”[12]

The Four Graves Attributed to a Confederate Battle with the Apache

At the spring, about one mile south of the station, was a battle between Confederate forces and the Apache on May 5, 1862. There are two primary reference to deaths and graves at this location, representing the four graves that are now visible north of the station. The first was this from a Union soldier with Colonel Carleton's Column from California to the Daily Alta California.

”Fort Thorn, July 10, 1862. Dragoon Springs. [June] 23rd.—At Dragoon Springs found water, but sufficient by using with care and patience. At night the surrounding mountains were alive with Indian fires. Near the stage station are the graves of Hunter’s men, killed by Apaches. On the graves were these inscriptions, neatly cut in rough stone, executed by one of the Union prisoners they had along: ‘S. Ford, May 5th, 1862.’ ‘Ricardo.’ Ford was a Sergeant, and Ricardo was a poor Mexican boy the Texans had forced into service at Tucson.”[13]

The second account is from Carleton himself. While there are no known Confederate Army orders documenting their battle with the Apache, an original letter that is cited by Historian L. Boyd Finch, in his Confederate Pathway to the Pacific, wherein he devoted part of a chapter to the battle. In a footnote Finch gives a reference for the battle near the station from a Union Order given by Colonel (soon to be General) Carleton. The relevant section of the original letter is quoted here:

”The rebels, from the best information I can get, have retired from Arizona toward the Rio Grande. The Apaches attacked Captain Hunter’s company of Confederate troops near Dragoon Spring and killed 4 men and ran off 30 mules and 25 horses.”[14]

As can be seen in the report it states that “near Dragoon Spring and killed 4 men,” and while it does not state that this occurred at the station or even that they were buried there, the likelihood is high that they were buried there given the archaeological evidence. (In L. Boyd Finch's footnote, which gives the Union Order as a reference, he did not accurately paraphrase the order by stating “Carleton himself later told of the Rebel graves there.)”[15] This is however, irrelevant to the argument, which from the report cited above notes that four confederates were killed, which is consistent with the number of graves visible in one area of the site, two of which have grave markers which identify two of the individuals by name.

Another statement is found about the 1862 battle in a Sacramento newspaper:

”Correspondent of the Union, Mesilla (A. T.), September 15th, 1862, The California Column. Dragoon Springs are situated in a canon one mile from the road. It was here that a portion of Hunter’s (secesh) party were attacked by the Apaches, who drove off their stock and killed three Texans, whose graves are near the entrance to the canon.”[16]

The mouth of the canon is at the point where the Dragoon Mountains meet the plain and is about one-half mile from Dragoon Springs Stage Station. While the description given may seem contradictory it is common for historical sources to convey terrain and landscape descriptions that are quite different from how we might perceive these today. The description is really not that far off from reality. Moreover, this article mentions only three Texans were killed instead of four, but this is very likely explained by the fact that at this time, the Mexican boy would not have been referenced as a Texan and, owing to this bias, the Mexican boy, who might not even have been enlisted, was not mentioned by this writer.

While it may seem that there is some contradiction concerning exactly who is buried under the four visible rock cairns seen just north of the station gate, when the documents are carefully examined and assessed there are really no contradictions and the burials are quite easily explained.

The 1967 Desecration of Confederate Soldier S. Ford’s Grave and Removal of his Remains and disturbance of the Rock Cairn over one of the Butterfield Employee’s Grave

Regrettably, damage was done to the Confederate rock cairns in 1967. One of the Confederate graves was disturbed and the grave of S. Ford was desecrated and the body removed. On June 9, 1967 a United States Government, Department of Agriculture—Forest Service report was issued concerning the desecration.

Violation of the American Antiquities Act of June 8, 1906 upon the Butterfield Stage Route (Dragoon Springs Station) was found upon personal inspection of the site on June 6, 1967. One of the graves of the historic massacre on September 8, 1858 was disturbed at some time previous to this inspection of June 6th. The grave of Ford was excavated and the body or its remnants removed.[17]

A follow up of the desecration was given by the Coronado National Forest Willcox Ranger District.

”The common grave is that of the individuals killed in the Station construction massacre. It is unmarked.”[18]

As the six visible graves are identified both visually and by the National Forest Service desecration reports, the graves are identified as the result of the massacre of Butterfield's Overland Mail Company employees and those of a Confederate and Apache battle on May 5, 1862.

A photo taken by Roscoe P. Conkling and Margaret B. Conkling on December 22, 1929, which when compared to the rock cairns today, show a distinct structural difference.[19] This is common as people loot graves in hopes of finding treasure. Another Conkling 1929 photo shows the carved stone marker for S. Ford on top of one of the rock cairns, but they did not mention which cairn. This marker is now cemented at the base of one of the cairns. Is it the same cairn as that shown in this photo? Also, there was no mention of Ricardo's stone marker. Consequently, the identification of specific graves must remain in question among the Confederate graves.

A chronological record of the Confederate Army engagements in early May 1862, which were between Tucson and Dragoon Springs Stage Station also adds clarity:

”May 5, 1862. 3 soldiers killed, incl. Sgt. Samuel B. Ford; 2 soldiers wounded, 1 Mexican killed: Ricardo; 17 horses captured; 21 mules captured; 16 cattle captured. Attack by Chiricahua (Chokonen) and Western Apaches (White Mountain), under Cochise and Francisco, on Confederate soldiers det. Co. A, Baylor’s Regt. Tex. Mtd. Rifles, C.S.A., under Sgt Ford, with a herd of livestock. In a canyon, 1-2 miles west of Dragoon Springs Station. (AZ). Nine Union prisoners were kept under guard at Dragoon Springs by 17 Confederate soldiers under Sgt. Ford. The former were given arms to fight the Apaches. Ford’s party was en route to San Pedro R. to water their stock. Two of the four graves near the station site probably hold the remains of three Overland Mail employees slain by Mexican workers in September 1858, which casts doubt on the number killed in the ambush.

May 5, 1862. 4 civilians killed: John Donaldson, Pope, Lamison and son; 1 Mexican killed (boy). Ambush by Apache Indians of civilians. Halfway between Tucson and Rillito Creek (AZ). Lamison is also identified as Lameson or Lameson. Location is also given as “Lowell Road.” Date and number of victims bear similarities to the ambush near Dragoon Springs (see previous entry), but geographical description suggest near Tucson. The same Indians probably remained in the vicinity, preying on local herds, which triggered Lt. Swope’s sortie a few days later.

May 9, 1862. 5 Indians killed, cattle recovered (all). Attack by 30 Confederate soldiers Co. A, Baylor’s Regt. Tex. Mtd. Rifles, C. S. A., under Lt. Robert L. Swope, on Apache Indians following raid on John G. Capron and Hiram S. Steven’s herd. Near Tucson. (AZ)"[20]

Conclusion for the Identity of the Six Graves

While there were no Confederate Army orders detailing the battles with the Apache, the battle was likely impromptu, as most were and therefore would not have been subject to orders. What at first glance to some may appear to be conflicting accounts for the battles, location, and number killed, to a seasoned analyst, the inferences can be clearly drawn. A relatively definitive identification can be made for those buried under the four clearly visible rock cairns north of the station gate. These are the burials of the Confederate soldiers and the Mexican boy. It is evident from archaeological evidence and by the references given, that the rock cairns to the north covered the graves of four Confederates (3 Texas soldiers and a Mexican boy [Ricardo]). The two graves to the west of the structure enclose three massacred Overland Mail Company employees. Also, as noted by massacre survivor Silas St. John, his amputated arm was buried between the two graves to the west of the station structure.

An Interpretive Marker at the Graves

An interpretive marker at the graves should honor the massacred Overland Mail Company employees and those with Captain Hunter's forces that died in battle against the Apache. Information on the marker should be given for the 1967 removal of the remains of Confederate soldier S. Ford.

An important event happened at the station October 12, 1872, Chiricahua Apache chief Cochise and General O.O. Howard ended 11 bloody years of warfare with a treaty that granted the Apache much of what has become Cochise County as a reservation.[21][22]

See also

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Dragoon Spring

- Maj. Woods, The Texas Almanac for 1858, Galveston, 1857, "Overland Mail Route Between San Antonio, Texas, and San Diego, California," "Report to the Postoffice Department, "Table of distances, and from one watering-place to another from starting point," A few notes and distances from San Antonio to San Diego," and "Supplemental," pp. 139-150.

- Report of the Postmaster General, Post Office Department, March 3, 1859, 35th Congress, 2d Session, Senate, Ex. Doc. No. 48, pp. 1-12.

- Letter from The Postmaster General, Post-Office Department, Washington, D. C., January 13, 1881, "Contract with Overland Mail Company," 46th Congress, 3d Session, Senate, Ex. Doc. No. 21, pp. 1-36. Note: These outline the entire contract over its six year history including all the changes and the order dated March 2, 1861, to transfer the contract to the Central Overland Trail.

- Gerald T. Ahnert, The Butterfield Trail and Overland Mail Company in Arizona, 1858-1861, 2011, Canastota Press, Canastota, New York.

- John Warner Barber and Henry Howe, Our Whole Country or the Past and Present of the United States, Volume II, Cincinnati, 1861, pp. 1448-1449.

- "Mail at Last." Arizona Miner, Prescott, Arizona, May 18, 1867

- John Warner Barber and Henry Howe, Our Whole Country, Volume II, Cincinnati, 1863, pp. 1448 & 1449.

- The New York Reformer, Watertown, November 4, 1858, “Particulars of the Murder of Mr. James Burr and Companions.”

- Thomas Edwin Farish, History of Arizona, Vol. II, Phoenix, 1915, pp. 5-10.

- J. D. Irwin, M. D., U. S. Army, The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 1858, Vol. XLI, Blanchard and Lea, Philadelphia, 1861.

- From a letter by Silas St. John to Miss Sharlot Hall, Dewey, AZ. The original is in the Sharlot Hall Museum, Prescott, Arizona. (Italics in the quote for emphasis)

- Daily Alta California, August 10, 1862, “DIARY OF THE MARCH TO THE RIO GRANDE.”

- The War of the Rebellion, A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I—Volume L—In Two Parts, Part I—Reports, Correspondence, Etc., Washington, Government Printing Office, 1897, Headquarters Column from California, Fort Barrett, Pima Villages, Ariz. Ter., May 24, 1862, Carleton to Drum, p. 1095.

- L. Boyd Finch, Confederate Pathway to the Pacific, The Arizona Historical Society, Tucson, 1996, pp. 150-153. The reference that was paraphrased incorrectly is in “Notes to Chapter Sixteen, number 5 on page 269.

- Sacramento Daily Union, California, October 18, 1862.

- United States Government Memorandum, Department of Agriculture—Forest Service, File No. 2760, June 9, 1967

- Coronado National Forest, Willcox Ranger District, Willcox, Arizona, to Mr. Peter Cowgill, Tucson, Arizona, July 7, 1970.

- Seaver Center for Western History Research Natural History Museum, Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California, 80007, File GC 1006, Box 5, Folder 09b, Dragoon Springs Station.

- Berndt Kühn, Chronicles of War: Apache & Yavapai Resistance in the Southwestern United States and Mexico, Publications Division, Arizona Historical Society, Tucson, AZ. May 5, 1862 battle at Dragoon Springs: Jones and Durnett to Carleton, May 24, 1862, Unreg. Letters and Telegrams Received, Pacific Dept., RG 393, NA; Carleton to Drum, May 24, 1862, Letters and Telegrams Received, Pacific Dept., RG 393, NA; San Francisco Call, June 11, 1862; Sacramento Daily Union, October 18, 1862; Prescott Courier, March 30, 1912; Finch, Confederate Pathway, 151-53; Sweeny, Cochise, 194. May 5, 1862 battle east of Tucson: Arizona Weekly Citizen, July 12, 1884, Obituary of John Donaldson, in Proceedings of a Board of Officers, Convened at Tucson, Arizona Territory, June 17, 1862,” and Mowry to Drum, July 24, 1862, in Sylvester Mowry, Sacks Biographical Files, MSS 155, AHF; Apache Raids Statistics, MS 381, AHS; Nathan B. Appel, in Hayden Biographical files, AHS. May 9, 1862 battle: Sacramento Daily Union, October 18, 1862, Prescott Courier, March 9, 1912, Finch, Confederate Pathway, p. 153.

- Deni J. Seymour and George Robertson, 2008 A Pledge of Peace: Evidence of the Cochise-Howard Treaty Campsite. Historical Archaeology 42(4):154-179.

- Doug Hocking, Tom Jeffords--Friend of Cochise, A TwoDot Book, Roman & Littlefield, National Book Network, 2017, Gilford Connecticut & Helena, Montana.