Ecotone

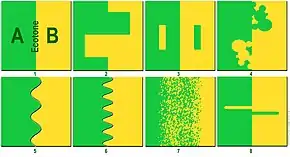

An ecotone is a transition area between two biological communities,[1] where two communities meet and integrate.[2] It may be narrow or wide, and it may be local (the zone between a field and forest) or regional (the transition between forest and grassland ecosystems).[3] An ecotone may appear on the ground as a gradual blending of the two communities across a broad area, or it may manifest itself as a sharp boundary line.

The word ecotone was coined by Alfred Russel Wallace, who first observed the abrupt boundary between two biomes in 1859. It is formed as a combination of ecology plus -tone, from the Greek tonos or tension – in other words, a place where ecologies are in tension.

Features

There are several distinguishing features of an ecotone. First, an ecotone can have a sharp vegetation transition, with a distinct line between two communities.[4] For example, a change in colors of grasses or plant life can indicate an ecotone. Second, a change in physiognomy (physical appearance of a plant species) can be a key indicator. Water bodies, such as estuaries, can also have a region of transition, and the boundary is characterized by the differences in heights of the macrophytes or plant species present in the areas because this distinguishes the two areas' accessibility to light.[5] Scientists look at color variations and changes in plant height. Third, a change of species can signal an ecotone. There will be specific organisms on one side of an ecotone or the other.

Other factors can illustrate or obscure an ecotone, for example, migration and the establishment of new plants. These are known as spatial mass effects, which are noticeable because some organisms will not be able to form self-sustaining populations if they cross the ecotone. If different species can survive in both communities of the two biomes, then the ecotone is considered to have species richness; ecologists measure this when studying the food chain and success of organisms. Lastly, the abundance of introduced species in an ecotone can reveal the type of biome or efficiency of the two communities sharing space.[6] Because an ecotone is the zone in which two communities integrate, many different forms of life have to live together and compete for space. Therefore, an ecotone can create a diverse ecosystem.

Formation

Changes in the physical environment may produce a sharp boundary, as in the example of the interface between areas of forest and cleared land. Elsewhere, a more gradually blended interface area will be found, where species from each community will be found together as well as unique local species. Mountain ranges often create such ecotones, due to the wide variety of climatic conditions experienced on their slopes. They may also provide a boundary between species due to the obstructive nature of their terrain. Mont Ventoux in France is a good example, marking the boundary between the flora and fauna of northern and southern France.[7] Most wetlands are ecotones. The spatial variation of ecotones often form due to disturbances, creating patches that separate patches of vegetation. Different intensity of disturbances can cause landslides, land shifts, or movement of sediment that can create these vegetation patches and ecotones.[8]

Plants in competition extend themselves on one side of the ecotone as far as their ability to maintain themselves allows. Beyond this competitors of the adjacent community take over. As a result, the ecotone represents a shift in dominance. Ecotones are particularly significant for mobile animals, as they can exploit more than one set of habitats within a short distance. The ecotone contains not only species common to the communities on both sides; it may also include a number of highly adaptable species that tend to colonize such transitional areas.[3] The phenomenon of increased variety of plants as well as animals at the community junction is called the edge effect and is essentially due to a locally broader range of suitable environmental conditions or ecological niches.

Ecotones and ecoclines

An ecotone is often associated with an ecocline: a "physical transition zone" between two systems. The ecotone and ecocline concepts are sometimes confused: an ecocline can signal an ecotone chemically (ex: pH or salinity gradient), or microclimatically (hydrothermal gradient) between two ecosystems.

In contrast:

- an ecocline is a variation of the physicochemical environment dependent of one or two physico-chemical factors of life, and thus presence/absence of certain species.[9] An ecocline can be a thermocline, chemocline (chemical gradient), halocline (salinity gradient) or pycnocline (variations in density of water induced by temperature or salinity).

- ecocline transitions are less distinct (less clear-cut), have more stable conditions within, hence a higher plant species richness.[10]

- an ecotone describes a variation in species prevalence and is often not strictly dependent on a major physical factor separating one ecosystem from another, with resulting habitat variability. An ecotone is often unobtrusive and harder to measure.

- an ecotone is the area where two communities interact. Ecotones can be easily identified by distinct change in soil gradient and soil composition between two communities.[11]

- ecotone transitions are more clear-cut (distinct), conditions are less stable, hence they have a low species richness.[10]

Examples

- The Kra ecotone between 11°N and 13°N latitude just north of the Kra Isthmus that connects the Thai-Malay Peninsula with mainland Asia is an example of a regional scale ecotone.[12] It marks the transition zone between the moist deciduous forest in the mainland Southeast Asia biogeographical region in the north and the wet seasonal dipterocarp forest in the Sundaland region in the south.[12] It has been shown to be the biogeographical transition between Indochinese and Sundaic faunas.[13] Approximately 152 species of bird were found to have northern or southern range limits between these latitudes.[13] Population genetics studies have also found that the Kra ecotone is the major physical barrier that limits gene flow in the honeybees Apis cerana and Apis dorsata and the stingless bees Trigona collina and Trigona pagdeni.[14]

- The Wallace Line running through the Lombok Strait between the Indonesian islands of Bali and Lombok is a faunal boundary that separates the Indomalayan realm from Wallacea.[15] It is named for Alfred Russel Wallace, who first observed the abrupt boundary between the two biomes in 1859. Biologists believe it was the depth of the Lombok Strait itself that kept the animals on either side isolated from one another. However, it has been found that some flightless animals such as certain weevil species have, in the past, been involved in several transgression events in which species from land east of the Wallace Line relocated to Bali.[16] When sea levels dropped during the Pleistocene ice age, the islands of Bali, Java and Sumatra were all connected to one another and to the mainland of Asia. They shared the Asian fauna. The Lombok Strait's deep water kept Lombok and the Lesser Sunda archipelago isolated from the Asian mainland. These islands were, instead, colonized by Australasian fauna.

- Mbam Djerem National Park's ecotone in Cameroon is up to 1,000 km wide in places and differences within species are believed to be precursors to speciation.[17]

- General examples of ecotones include salt marshes and riparian zones.

See also

References

- Senft, Amanda (2009). Species Diversity Patterns at Ecotones (Master's thesis). University of North Carolina.

- Pearl, Solomon Eldra; Berg, Linda R.; Martin, Diana W. (2011). Biology. Belmont, California: Brooks/Cole.

- Smith, Robert Leo (1974). Ecology and Field Biology (2nd ed.). Harper & Row. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-06-500976-7.

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Ecotone.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 23 Jan. 2012, www.britannica.com/science/ecotone.

- Janauer, G.A (1997). "Macrophytes, hydrology, and aquatic ecotones: A GIS-supported ecological survey". Aquatic Botany. 58 (3–4): 379–91. doi:10.1016/S0304-3770(97)00047-8.

- Walker, Susan; Wilson, J. Bastow; Steel, John B; Rapson, G.L; Smith, Benjamin; King, Warren McG; Cottam, Yvette H (2003). "Properties of ecotones: Evidence from five ecotones objectively determined from a coastal vegetation gradient". Journal of Vegetation Science. 14 (4): 579–90. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2003.tb02185.x.

- Kubisch, P; Leuschner, C; Coners, H; Gruber, A; Hertel, D (2017). "Fine Root Abundance and Dynamics of Stone Pine (Pinus cembra) at the Alpine Treeline Is Not Impaired by Self-shading". Front Plant Sci. 8: 602. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00602. PMC 5395556. PMID 28469633.

- https://andrewsforest.oregonstate.edu/sites/default/files/lter/pubs/pdf/pub1056.pdf

- Maarel, Eddy (1990). "Ecotones and ecoclines are different". Journal of Vegetation Science. 1 (1): 135–8. doi:10.2307/3236065. JSTOR 3236065.

- Backeus, Ingvar (1993). "Ecotone Versus Ecocline: Vegetation Zonation and Dynamics Around a Small Reservoir in Tanzania". Journal of Biogeography. 20 (2): 209–18. doi:10.2307/2845672. JSTOR 2845672.

- Brownstein, G; Johns, C; Fletcher, A; Pritchard, D; Erskine, P. D (2015). "Ecotones as indicators: Boundary properties in wetland-woodland transition zones". Community Ecology. 16 (2): 235–43. doi:10.1556/168.2015.16.2.11.

- Smith, Deborah R (2011). "Asian Honeybees and Mitochondrial DNA". Honeybees of Asia. pp. 69–93. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-16422-4_4. ISBN 978-3-642-16421-7.

- Hughes, Jennifer B; Round, Philip D; Woodruff, David S (2003). "The Indochinese-Sundaic faunal transition at the Isthmus of Kra: An analysis of resident forest bird species distributions". Journal of Biogeography. 30 (4): 569–80. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00847.x.

- Theeraapisakkun, M; Klinbunga, S; Sittipraneed, S (2010). "Development of a species-diagnostic marker and its application for population genetics studies of the stingless bee Trigona collina in Thailand". Genetics and Molecular Research. 9 (2): 919–30. doi:10.4238/vol9-2gmr775. PMID 20486087.

- Alfano, Niccolò; Michaux, Johan; Morand, Serge; Aplin, Ken; Tsangaras, Kyriakos; Löber, Ulrike; Fabre, Pierre-Henri; Fitriana, Yuli; Semiadi, Gono; Ishida, Yasuko; Helgen, Kristofer M; Roca, Alfred L; Eiden, Maribeth V; Greenwood, Alex D (2016). "Endogenous Gibbon Ape Leukemia Virus Identified in a Rodent (Melomys burtoni subsp.) from Wallacea (Indonesia)". Journal of Virology. 90 (18): 8169–80. doi:10.1128/JVI.00723-16. PMC 5008096. PMID 27384662.

- Tanzler, R; Toussaint, E. F. A; Suhardjono, Y. R; Balke, M; Riedel, A (2014). "Multiple transgressions of Wallace's Line explain diversity of flightless Trigonopterus weevils on Bali". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1782): 20132528. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2528. PMC 3973253. PMID 24648218.

- Steve Nadis (11 June 2016). "Life on the edge". New Scientist.

External links

| Look up ecotone in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |