Education in Mexico

Education in Mexico has a long history. The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico was founded by royal decree in 1551, a few months after the National University of San Marcos in Lima. By comparison, Harvard College, the oldest in the United States, was founded in 1636 and the oldest Canadian University, Université Laval dates from 1663. Education in Mexico was, until the twentieth century, largely confined to males from the urban and aristocratic elite and under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico.

| |

| Secretariat of Public Education | |

|---|---|

| Secretary of Education Deputy Secretary | Esteban Moctezuma Barragán |

| National education budget (2007) | |

| Budget | MXN$200,930,557,665 USD$20B[1] |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | Spanish as the standard. Other minority languages are available in their local communities. |

| System type | Federal |

| Current system | September 25, 1921 |

| Literacy (2012) | |

| Total | 95.1%[2] |

| Male | 96.2% |

| Female | 94.2% |

| Enrollment | |

| Total | 26.6 million |

| Primary | 18.5 million |

| Secondary | 5.8 million |

| Post secondary | 2.3 million |

| Attainment | |

| Secondary diploma | n/a |

| Post-secondary diploma | n/a |

| Sources: Sistema Educativo de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Principales cifras, ciclo escolar 2003–2004 pdf and the 2000 Census (INEGI) | |

The Mexican state has been directly involved in education since the nineteenth century, promoting secular education. Control of education was a source of an ongoing conflict between the Mexican state and the Roman Catholic Church, which since the colonial era had exclusive charge of education.[3][4][5][6] The mid-nineteenth-century Liberal Reform separated church and state, which had a direct impact on education. President Benito Juárez sought the expansion of public schools. During the long tenure of President Porfirio Díaz, the expansion of education became a priority under a cabinet-level post held by Justo Sierra; Sierra also served President Francisco I. Madero in the early years of the Mexican Revolution.

The 1917 Constitution strengthened the Mexican state's power in education, undermining the power of the Roman Catholic Church to shape the educational development of Mexicans. During the presidency of Álvaro Obregón in the early 1920s, his Minister of Public Education José Vasconcelos implemented a massive expansion of access to public, secular education and expanded access to secular schooling in rural areas. This work was built on and expanded in the administration of Plutarco Elías Calles by Moisés Sáenz. In the 1930s, the Mexican government under Lázaro Cárdenas mandated socialist education in Mexico and there was considerable push back from the Roman Catholic Church as an institution. Socialist education was repealed during the 1940s, with the administration of Manuel Ávila Camacho. A number of private universities have opened since the mid-twentieth century. The Mexican Teachers' Union (SNTE), founded in the late 1940s, has had tremendous national political power. The Mexican federal government has undertaken reforms to improve education in Mexico, which have been resisted by the SNTE.

Education in Mexico is currently regulated by the Secretariat of Public Education (Spanish: Secretaría de Educación Pública) (SEP). Education standards are set by this Ministry at all levels except in "autonomous" universities chartered by the government (e.g., Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México). Accreditation of private schools is accomplished by mandatory approval and registration with this institution. Religious instruction is prohibited in public schools; however, religious associations are free to maintain private schools, which receive no public funds.

In the same fashion as other education systems, education has identifiable stages: Primary School, Junior High School (or Secondary School), High School, Higher education, and Postgraduate education.

Structure of the basic education system

In Mexico, basic education is normally divided in three steps: primary school (primaria), comprising grades 1–6; junior high school (secundaria), comprising grades 7–9; and high school (preparatoria), comprising grades 10–12.

Depending on definitions, Primary education comprises primaria and secundaria, which are compulsory by law, while Secondary education only includes preparatoria, which was not compulsory a few years ago, but it has been made mandatory as well.

Primary school

The terms "Primary School" or "Elementary School" usually corresponds to primaria, comprising grades 1–6, when the student's offer is 6 to 12 years old. It starts the basic compulsory education system. These are the first years of schooling.

Depending on the school, bilingual education may be offered from the beginning, where half the day instruction is in Spanish, and the rest is in a second language, for example, English or French.

Junior high school

The terms "Junior High School" or "Middle School" usually correspond to secundaria, comprising grades 7–9 when the student's age is 12 to 15 years old. It is part of the basic compulsory education system, following primary school and coming before "high school" (preparatoria).

At this level, more specialized subjects may be taught such as Physics, Chemistry, and World History. There is also the técnica which provides vocational training, and the telesecundaria which provides distance learning.[7]

Despite the similarities of the words "Secondary school" and secundaria, in Mexico the former is usually translated to preparatoria, while in other countries, such as Puerto Rico, or within the Spanish-speaking populations of the United States, the term secundaria refers to university.

High school

The terms "High School"[8] usually corresponds to preparatoria or bachillerato, and follow "secundaria" comprising grades 10–12, when the student's age is 15 to 18 years old. Students may choose between two main kinds of high school programs: The SEP incorporated, and a University Incorporated one, depending on the state. Other minority of programs are available only for private schools, such as the International Baccalaureate which carries a completely different system. Nevertheless, in order to be taught, it must include a national subject at least. In addition, there are programs such as tecnología and comercio that prepare students for a particular vocational career.[7]

Preparatoria traditionally consists of three years of education, divided into six semesters, with the first semesters having a common curriculum, and the latter ones allowing some degree of specialization, either in physical sciences (physics, chemistry, biology, etc.) or social sciences (commerce, philosophy, law, etc.). The term preparatoria is most commonly used for institutions that offer a three-year education program that "prepares" the student with general knowledge to continue studying at a university. In contrast, the term bachillerato is most often used for institutions that provide vocational training, in two or three years, so the graduate can get a job as a skilled worker, for example, an assistant accountant, a bilingual secretary or a technician.

Educational integration

In 1993, educational integration was formally implemented nationwide through the reform article 41 of the General Education Law. This law mandates the integration of students with special needs into regular classrooms.[12] Although formally, the term ‘educational integration’ is used, ‘inclusive education’ is often used to describe the educational system.[13] Implementation of educational integration has taken many years and still continues to face obstacles. Under the current model, students with severe disabilities that would not benefit from inclusion, study the same curriculum as regular classrooms in separate schools called Centros de Atencion Multiple [Multiple Attention Center], or CAM. Otherwise, special needs students are placed in regular classrooms and are supported by the Unidades de Servicio y Apoyo a la Educación Regular or the Unit of Support Services for Regular Education, (USAER). This group is made up of special education teachers, speech therapists, psychologists and other professionals to help special needs students in the classroom and minimize barriers to their learning.[13]

Challenges to educational integration

.jpg.webp)

The combination of USAER professionals and regular teaching working in the same classroom has caused some issues for educational integration. Specifically, there is confusion about the roles of USAER professionals who work in regular classrooms. A study of USAER members found that regardless of urban or rural contexts, professionals had four common concerns. First, USAER professionals felt that they lacked preparation for working in the classroom. The second issue was feeling like their role had changed due to more demands being placed on them. The last two concerns were the lack of communication and collaboration between teachers and USAER professionals. Although the two work in the same classroom, they often work independently. However, this creates problems when adjusting the curriculum for special needs students.[13]

Accessibility is another challenge for educational integration. Schools are required to have accessible buildings and classrooms, provide technical support and appropriate materials for special needs students,[14] but a case study found that the school was not equipped for students with sensory disabilities. The school lacked accessible furniture, handicapped restrooms or proper modification for students with sensory disabilities.[14]

Finally, training for new teachers doesn't provide them enough experience with special needs students, making the shift to educational integration difficult. A study of 286 pre-service teachers found that a third of didn't have any experience working with special needs students. Additionally, 44% of the teachers reported having no formal training in working with this population.[15] A qualitative study on pre-service teachers assessed their attitude towards special needs students and their self-efficacy found that overall most teachers have positive perceptions of inclusive education. However, teachers with more hours of training, more teaching experience, and better knowledge of policies had higher levels of confidence in working with students with disabilities.[16]

Quality of education in Mexico

In recent years, the progression through Mexican education has come under much criticism. While over 90% of children in Mexico attend primary school, only 62% attend secondary school. Only 45% finish secondary school. After secondary school, only a quarter pass on to higher education.[17] A commonly cited reason for this is the lack of infrastructure throughout the rural schools. Moreover, the government has been criticized for paying teachers too much and investing too little into the students. In its 2012 report on education, the OECD placed Mexico at below average in mathematics, science, and reading.[18]

A program of education reform was enacted in February 2013 which provided for a shift in control of the education system from the teachers union SNTE and its political boss, Elba Esther Gordillo, to the central and state governments. Education in Mexico had been controlled by the teachers union and its leaders for many years.[19] Shortly thereafter Gordillo was arrested on racketeering charges.[20] As of 2016 the government continued to struggle with the union and its offshoot, CNTE.[21]

Higher education

There are both public and private institutions of higher education. Higher education usually follows the US education model with an at least 4-year bachelor's degree undergraduate level (Licenciatura), and two degrees at the postgraduate level, a 2-year Master's degree (Maestría), and a 3-year Doctoral degree (Doctorado), followed by the higher doctorate of Doctor of Sciences (Doctor en Ciencias). This structure of education very closely conforms to the Bologna Process started in Europe in 1999, allowing Mexican students to study abroad and pursue a master's degree after Licenciatura, or a Doctoral degree after Maestría. Unlike other OECD countries, the majority of Mexico's public universities do not accredit part-time enrollment programs.[22][23]

Undergraduate studies

Undergraduate studies normally last at least 4 years, divided into semesters or quarters, depending on the college or university, and lead to a bachelor's degree (Licenciatura). According to OECD reports, 23% of Mexicans aged 23–35 have a college degree.

Although in theory every graduate of a Licenciatura is a Licenciate (Licenciado, abbreviated Lic.) of his or her profession, it is common to use different titles for common professions such as Engineering and Architecture.

- Engineer, Ingeniero, abbreviated Ing.

- Electrical Engineer, Ingeniero Eléctrico

- Electronics Engineer, Ingeniero Electrónico

- Mechanical Engineer, Ingeniero Mecánico

- Computer Systems Engineer, Ingeniero en Sistemas Computacionales, abbreviated I.S.C.

- Architect, Arquitecto, abbreviated Arq.

- Licenciate, any degree, especially those from social sciences, Licenciado, abbreviated Lic.

Postgraduate studies

New regulations since 2005 divide postgraduate studies at Mexican universities and research centers in two main categories:[24]

- Targeted at professional development

- Especialización. A 1-year course after a bachelor's degree (Licenciatura), which awards a Specialization Diploma (Diploma de Especialización).

- Maestría. A 2-year degree after a bachelor's degree (Licenciatura), which awards the title of Master (Maestro).

Targeted at scientific research

- Maestría en Ciencias. A 2-year degree after a bachelor's degree (Licenciatura), which awards the title of Master of Science (Maestro en Ciencias).

- Doctorado. A 3-year degree after a master's degree (either Maestría or Maestría en Ciencias), or a 4-year degree directly after the bachelor's degree (Licenciatura) for high-achieving students. The Doctor of Sciences degree (Doctor en Ciencias) is equivalent to the higher doctorate awarded in countries such as Denmark, Ireland, the UK, and the former USSR countries.

Intercultural Universities

Intercultural Universities in Mexico were established in 2004 in response to the lack of enrollment of the indigenous population in the country. While an estimated 10% of the population of Mexico is indigenous, it is the least represented in higher education. According to estimates, only between 1% and 3% of higher education enrollment in Mexico is indigenous. In response to this inequality, the General Coordination for Intercultural and Bilingual Education at the Ministry of Education established Intercultural Universities with the active participation of indigenous organizations and academic institutions in each region.[25]

International education

As of January 2015, the International Schools Consultancy (ISC)[26] listed Mexico as having 151 international schools.[27] ISC defines an 'international school' in the following terms "ISC includes an international school if the school delivers a curriculum to any combination of pre-school, primary or secondary students, wholly or partly in English outside an English-speaking country, or if a school in a country where English is one of the official languages, offers an English-medium curriculum other than the country’s national curriculum and is international in its orientation."[27] This definition is used by publications including The Economist.[28]

Educational years

School years

The table below describes the most common patterns for schooling in the state sector:

| Minimum age | Year | Months | Schools | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | N/A | N/A | Nursery | Maternal | |

| 3 | 1° de preescolar | N/A | Preschool | Kinder / Jardín de Niños / Educación preescolar | |

| 4 | 2° de preescolar | N/A | |||

| 5 | 3° de preescolar | N/A | |||

| 6 | 1° de primaria | N/A | Primary school / Elementary school | Primaria / Educación básica | |

| 7 | 2° de primaria | N/A | |||

| 8 | 3° de primaria | N/A | |||

| 9 | 4° de primaria | N/A | |||

| 10 | 5° de primaria | N/A | |||

| 11 | 6° de primaria | N/A | |||

| 12 | 1° de secundaria | N/A | Secondary school / Middle school / Junior High School | Secundaria / Educación básica | |

| 13 | 2° de secundaria | N/A | |||

| 14 | 3° de secundaria | N/A | |||

| 15 | 4°/1° de preparatoria | 1st and 2nd semesters | High school | Preparatoria / Bachillerato / Educación media superior | |

| 16 | 5°/2° de preparatoria | 3rd and 4th semesters | |||

| 17 | 6°/3° de preparatoria | 5th and 6th semesters | |||

| 18 | N/A | 1st and 2nd semesters / 1st, 2nd and 3rd quarters | Associate degree at two-year institutions and if four-year then a Bachelor's degree / Licentiate | Carrera Técnica and Licenciatura / Educación superior | |

| 19 | N/A | 3rd and 4th semesters / 4th, 5th and 6th quarters | |||

| 20 | N/A | 5th and 6th semesters / 7th, 8th and 9th quarters | |||

| 21 | N/A | 7th and 8th semesters / 10th quarter | |||

| 22 | N/A | 9th and 10th semester (in most of the cases) | |||

| N/A | N/A | ... | Master's degree | Maestría | |

| N/A | N/A | ... | Doctorate | Doctorado | |

History of education

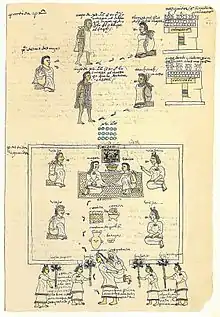

(top) Formal education of 15-year-old Aztec boys trained for the military or the priesthood.

(bottom) A 15-year-old girl gets married.

In central Mexico, the history of education stretches back to the Prehispanic era, with the education of Nahuas in schools for elites and commoners. A formal system of writing was created in various parts of central and southern Mexico, with trained experts in its practice. After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, friars embarked on a widespread program of evangelization of Christianity. In the colonial era, schooling of elite men of European descent was established under the auspices of the Catholic Church. Liberals' attempts to separate church and state in post-independence Mexico included removal of the Catholic Church from education. Education remains an important aspect of Mexican institutional and cultural life, and conflicts continue about how it should be conducted. The history of education in Mexico gives insight into the larger history of the nation.

Education in Mesoamerica Before the Spanish

In central Mexico in the cultural area known as Mesoamerica, the Aztecs set up schools called calmecac for the training of warriors and schools for the training of priests, called cuicacalli. An early post-conquest manuscript prepared by native scribes for the viceroy of Mexico, Codex Mendoza shows these two types of schools. Aztec religion was highly complex and priests held a higher status, so that the creation of schools to train them in ritual and other aspects of religion was important. Overseeing an expansionist empire, Aztec rulers needed trained warriors, so that the creation of formal schools for their training was as important.

Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec god of wind, air, and learning, wears around his neck the "wind breastplate" ehecailacocozcatl, "the spirally voluted wind jewel" made of a conch shell. This talisman was a conch shell cut at the cross-section and was likely worn as a necklace by religious rulers, as such objects have been discovered in burials in archaeological sites throughout Mesoamerica.[29]

Colonial-era education, 1521–1821

Education of the indigenous in Central Mexico

The Spanish Crown made a significant commitment to education in colonial New Spain. The first efforts of schooling in Mexico were friars’ evangelization of indigenous populations. “Educating the native population was a crucial justification of the colonizing enterprise, and that criollo (Spanish American) culture was encouraged as a vehicle for integrating” the indigenous.[30] Fray Pedro de Gante established schools for indigenous in the immediate post-conquest years and produced pictorial texts to teach Catholic doctrine. All the mendicant orders in Mexico, the Franciscans, Dominicans, and Augustinians, built churches in large indigenous communities as places of worship and to teach the catechism, so that large outdoor atriums functioned as classrooms.[31] Elite indigenous lads were tapped for training as catechists and helpers to the priests, whose small numbers could in no way minister to large numbers of ordinary indigenous.

In 1536, the Franciscans and the Spanish crown established a school to train an indigenous Catholic priesthood, the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, which was deemed a failure in its goal of training priests, but did create a small cohort of indigenous men who were literate in their native language of Nahuatl, as well as Spanish and Latin. The Franciscans also founded the school of San José de los Naturales in Mexico City, which taught trades and crafts to boys. The Colegio de San Gregorio was also founded for the education of indigenous elites, the most famous of whom was Chimalpahin, (also known as Don Domingo Francisco de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin).

Religious orders, particularly the Franciscans, taught indigenous scribes in central Mexico to be literate in their own languages, allowing the creation of documents at the local level for colonial officials and communities to enable crown administration as well as production of last will and testaments, petitions to the crown, bills of sale, censuses and other types of legal record to be produced at the local level.[32] The large number of indigenous language documents found in the archives in Mexico and elsewhere have enabled scholars of the New Philology to analyze life of Mexico's colonial-era indigenous from indigenous perspectives. However, despite the large volume of documentation in indigenous languages, there is no evidence of that even elite indigenous women were literate.[33]

Education of elite Creole men

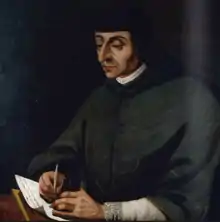

The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico was founded in September 1551 at the request by Mexico's first viceroy, Don Antonio de Mendoza to the Spanish crown. The university was located in the central core (traza) of History of Mexico City. Its first rector, Francisco Cervantes de Salazar, wrote an account of the university. The institution initially trained in priests, lawyers, and starting in 1579, medical doctors.[34] These were the traditional disciplines of the medieval and early modern eras. The Royal and Pontifical University was the sole institution that could confer academic degrees. With the title of royal and pontifical university, its degrees were titled the same as European degrees.[35] The Jesuits arrived in Mexico in 1571 and rapidly founded schools and colegios, and sought to confer degrees; however, the Council of the Indies, the royal entity overseeing the Spanish overseas empire, decided against them.[35]

The university retained its premier position. One of its best-known graduates was Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, a Mexican savant of the seventeenth century, who was a friend of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, a cloistered nun and intellectual, famous in her lifetime as the “Tenth Muse.” Sor Juana was barred from attending the university due to her gender.

In general, educational institutions were urban-based, with the capital Mexico City having the largest concentration. However, there were seminaries to train priests in provincial cities, such as the Colegio de San Nicolás, founded by Bishop Vasco de Quiroga in the city now called Morelia. Insurgent leader Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla served as rector there until he was relieved of his position. One of his students was insurgent leader Father José María Morelos. Educated priests were prominent in the movement toward independence from Spain.

Education of girls and mixed-race children

Most of the Mexican population was illiterate and entirely unschooled, and there was no priority for the education of girls.[36] A few girls in cities attended schools run by cloistered nuns. Some entered convent schools at around age eight, “to remain cloistered for the rest of their lives.”[37] There were some schools connected to orphanages or confraternities. Private tutors educated girls from wealthy families, but only enough so that they could oversee a household. There were few opportunities for mixed-race boys or girls. “Education was, in short, highly selective as befits a stratified society, and the possibilities of self-realization were a lottery of birth rather than talent.”[38]

National period – 1821–present

During the colonial era, education was under the control of the Catholic Church. Liberalism emerged as an ideology in the post-independence period, with a major tenet being public secular education. Conflict in the realm of education has been an ongoing issue in Mexican history since the Catholic Church sought to retain its role in this sphere, while liberals have sought to undermine the Church's role. Since the 1940s, Catholic universities have re-emerged. Unionized school teachers have become a powerful force in the late twentieth and early twenty-first-century Mexican politics.

Post-Independence Era, 1821–1850

When Antonio López de Santa Anna put his Liberal vice president Valentín Gómez Farías in charge of running the government, the vice president created in 1833 a public education system. This preceded the establishment of a Ministry of Public Education.[39] This reform was short-lived, but with the Liberal Reform in the mid-nineteenth century, a normal school for teacher training was established.[40] The Liberals push for public education awaited the end of the War of the Reform and the ousting of the French Empire in Mexico (1862–67). The restored Republic of President Benito Juárez reaffirmed the Liberals principle of separation of church and state, which in the educational sphere meant supplanting the Catholic Church by the Mexican state. Primary education in Mexico was henceforth to be secular, free of fees and tuition, and obligatory.[41]

Reform era, 1850–1876

A key figure in higher education in Mexico was Gabino Barreda, who chaired Juárez's commission on education in 1867.[42] Barreda was a follower of French intellectual Auguste Comte who established positivism the dominant philosophical school in the late nineteenth century.[43] The Juárez government created a system of secondary education, and a key institution was the National Preparatory School (Escuela Nacional Preparatoria), founded in 1868 in Mexico City, which Barreda directed.[42] Education at the Preparatoria was uniform for all students and "designed to fill what José Díaz Covarrubias identified as the traditional void between primary and professional training."[44]

Porfiriato, 1876–1910

During the Porfiriato (1876–1910), the era of Porfirio Díaz's presidency, secular, public education was a priority for the government, since it was seen as a vehicle for changes in behavior that would benefit the government's commitment to progress. The number of schools expanded and the federal government expanded centralized control. Municipal governments had to yield control to state governments, and the federal bureaucracy for public schooling was established under the Ministry of Education, a cabinet-level position. More money was spent on public schools in this era, increasing faster than other public expenditures. Public schooling was part of Mexico's project of modernization, to create an educated workforce. Those overseeing schools sought to instill the virtues of punctuality, thrift, valuable work habits, abstinence from alcohol and tobacco use, and gambling, along with creating a literate population. Although these were a lofty aim, implementation was hampered by poorly trained teachers who were poorly trained.[45] Illiteracy was widespread, with the 1910 census indicating only 33% of men and 27% of women were literate. Few students went on to secondary or post-secondary education. "Porfirian schools were more important in their production of middle-class talent for the post-revolutionary educational and cultural efforts than they were in transforming popular behavior and illiteracy."[46] However, the government's commitment to education under Justo Sierra was an important step. He established the secular, state-controlled Universidad Nacional de México; The Pontifical University of Mexico under religious authority was suppressed in 1865.

Women entered the teaching profession, which was considered a proper one for women who worked outside the home. Although the schools were aimed at creating an educated populace envisioned by Porfirian elites, quite a number of school teachers were active in opposing the Díaz regime and participated in the Mexican Revolution,[47] including Pascual Orozco and Plutarco Elías Calles. Women school teachers were important in the nascent women's rights movement, such as Rita Cetina Gutiérrez[48] and Dolores Jiménez y Muro.

1920–1940

Following the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), the government made a major commitment to public education under its control. Centralization of education was via the federal Ministry of Education (Secretaria de Educación Pública or SEP). José Vasconcelos became its head in 1921 and proceeded to enact a wide range of educational programs, including indigenous education. The so-called "Indian problem," the lack of incorporation of Mexico's indigenous population into the nation as citizens, was an issue that the SEP tackled. Indigenous children were not to be taught in separate schools in their own languages but taught in Spanish along with non-indigenous, mestizo students. An early program was the formation of "Missionaries of Indigenous Culture and Public Education," which had the aim of imparting a secular worldview emphasizing "community development, modernization, and incorporation into the mestizo mainstream."[49]

The federal government took over schools run by Mexican states and enrollments for rural primary schools increased significantly. Public schools became a means for the government to directly influence the countryside ideologically through education of the next generations. Public school teachers saw themselves "as part of a mystical crusade for the nation, modernity, and social justice," but SEP personnel often held campesinos and rural culture in contempt. In the 1930s, during the early presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–40) there was a push for "socialist education" at all levels. The policy made public schools sources of anti-religious ideology fueling resistance by Catholics.[51]

The government expanded normal schools for teacher training after the Mexican Revolution of 1910.[52] As the federal government consolidated power through the formation of the National Revolutionary Party (PNR) in 1928 and its new iteration in 1936, the Mexican Revolutionary Party (PRM), teachers played an important role in the creation of national worker and national peasant organizations. Public education "contributed to the consolidation of an authoritarian single-party regime."[53]

When the Mexican government implemented its policy of socialist education, it directly targeted religious-affiliated, private schooling. Students in these schools were barred from receiving valid educational certification, which effectively prevented many from entering professions. The aim of socialist education was to create a "useful and efficient worker capable of assuming leadership of the national economy, employing methods of modern science with a profound consciousness of collective responsibility ... an indispensable precondition for the coming of a state in the hands of the working classes."[54] The conflict was violent at the National University in Mexico City, which in 1929 had become autonomous from government control, but there was also conflict at regional universities as well, mainly student strikes. Cárdenas backed away from socialist education. Catholic student groups' mobilization against socialist education had lasting consequences, with leaders in the Catholic Student Union playing an important role in the founding of the conservative, pro-Catholic National Action Party in 1939.[55]

Education, post-1940

When President Cárdenas chose Manuel Avila Camacho as his successor, he chose a moderate, particularly on church-state issues where education was contentious. In office, Avila Camacho ended socialist education. Initially, the Ministry of Education continued various policies from the Cárdenas era, but with Avila Camacho's appointment of Jaime Torres Bodet as head of the SEP, government policy sought to raise educational standards and invest in teacher training. Torres Bodet founded the National Institute of Teacher Training. He sought to create a curriculum that was nationalist and democratic. "Education was to be secular, free of religious doctrine, and based on scientific truths."[56]

During the period ca. 1940–1960, Mexico experienced sustained economic growth, the so-called Mexican Miracle, which saw increased urbanization and industrialization. The idea that education was a determinant of economic development took hold and the government of President Adolfo López Mateos, who appointed Torres Bodet Minister of Education. Torres Bodet made a comprehensive assessment of Mexican education, which led to the Eleven-Year Plan for Education, attempting to make a commitment that forced the next president to continue implementation. The assessment of Mexican primary-level schools showed that 50% of Mexican children, or 3 million, had access to primary education. Of those, fewer than 25% finished 4th grade. Only about 1,000 of those primary school students would succeed in pursuing a profession. A basic finding was that only 50% of Mexicans could read or write. López Mateos sought reforms to remedy the situation, including training 27,000 more teachers and building more schools. He also created a program to provide free textbooks to students and made their use obligatory in schools.[57]

In 1949, Mexican teachers formed a national union that was affiliated with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and came to be a powerful bloc within it. The Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación (SNTE), (National Union of Education Workers) was formed as a section within the umbrella organization of the Confederation of Mexican Workers (CTM), the labor sector of the dominant party. In the late 1930s, teachers had begun to form unions that were eventually brought into the SNTE.

In 1968, when Mexico hosted the Olympic Games in the capital, there were widespread demonstrations against spending so much on such an event, when there were higher national priorities. University students participated in a major way in these demonstrations, with the government reacting violently in the Tlatelolco massacre of October 1968. In June 1971, there was further student activism in Mexico City that resulted in more violent government repression, known as the Corpus Christi massacre. Recognizing that failures in the educational system was a cause of the 1968 student activism, the government of Gustavo Díaz Ordaz (1964–1970) attempted to implement educational reform as part of a wider social reform. The government sought to reach Mexicans who had not had access to education previously and the use of radio and television were seen as ways to do this. Adult education became a focus of the expansion. With the presidency of Luis Echeverría (1970–1976), the expansion included the use of telenovelas (soap operas) to shape public understandings, and Mexico became a pioneer in the use of this medium for policy matters. Better health care in earlier years had resulted in a population boom as infant mortality declined and fertility increased. With Catholic Church opposition to birth control, the secular format of telenovela were a means to bring a message of the benefits of family planning to women.[58] The government sought to strengthen higher education particularly in the sciences and technology, establishing the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT) in 1970. It funds fellowships for graduate students to study abroad to increase their specialized knowledge. Despite sustained government efforts over several presidential administrations, Mexican education had not significantly affected low education levels and high levels of illiteracy in the country, especially in rural areas. President José López Portillo (1976–1982) created a National Literacy Program (Pronalf) in 1980 and then established an independent institute for adult education (Instituto Nacional de Educación para Adultos INEA).[59] With the collapse of the Mexican economy during the oil crisis of 1982, educational reform awaited economic recovery.

In 1992, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who became president in the disputed 1988 elections, instituted changes in the organization of Mexico's educational system. Adopting neoliberal economic policies to promote development, Salinas saw education as a key factor.[61] In an accord with the SNTE, education was decentralized from its control by the Ministry of Public Education (SEP) and came under the control of the Mexican state government. Curriculum reform was also undertaken by the SEP, which included the creation of new textbooks. Protests resulted in the government's withdrawing the textbooks.[62] A third component of the accord was the creation of a system of merit pay for teachers.[63]

.jpg.webp)

The SNTE grew to be the largest single labor union in Latin America, and its head, Elba Esther Gordillo considered the most powerful woman in Mexican politics.[64] The lack of democracy within the teachers' union has been as a source of conflict.[65] Also a source of conflict is union opposition to reforms that undercut union power over teaching positions. In 2012, some teachers from rural areas, specifically, from Michoacan and Guerrero states, opposed federal regulations that prevented them from automatic lifetime tenure, the ability to sell or will their jobs, and the teaching of either English or computer skills.[52][66] The head of the SNTE since 1989 was arrested in 2013 as she got off her private airplane in the Toluca airport, and charged with corruption.[64]

School attendance has increased over the years. In 1950, Mexico had only three million students enrolled in education. In 2011, there were 32 million enrolled students.[67] The 1960 national census illustrates the historically poor performance of the Mexican educational system. The 1960 census found that as to all Mexicans over the age of five, 43.7% had not completed one year of school, 50.7% had completed six years or less of school, and only 5.6% had continued their education beyond six years of school.[68] In 2015, 96.2% of six to fourteen year-olds attended school, up from 91.3% in 2000.[69] The state with the highest attendance rate was Hidalgo (97.8%) and the state with the lowest attendance rate was Chiapas (93%).[69] In the same year, 63% of three to five year-olds attended preschool or kindergarten, up from 52.3% in 2010.[69] Also in 2015, 44% of 15 to 24 year-olds attended secondary or tertiary school, an increase from 32.8% in 2000.[69]

In 2004, the literacy rate was at 97%[70] for youth under the age of 14 and 91% for people over 15,[71] placing Mexico at the 24th place in the world rank according to UNESCO.[72]

In February 2019, the SEP commemorated the establishment of the program for free textbooks with a publication noting the inclusion of art by Mexicans in successive textbook editions.[73]

The National Autonomous University of Mexico ranks 103th in the QS World University Rankings, making it the best university in Mexico, after it comes the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education as the best private school in Mexico and 158th worldwide in 2019.[74] Private business schools also stand out in international rankings. IPADE and EGADE, the business schools of Universidad Panamericana and of Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education respectively, were ranked in the top 10 in a survey conducted by The Wall Street Journal among recruiters outside the United States.[75]

See also

References

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2009-09-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "North America – Mexico". The World Factbook. U. S. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Pilar Gonzalbo Aizpuru, "Education: Colonial" in Encyclopedia or Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 434–438.

- Antonio Escobar Ohmstede, "Education: 1821–1989" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 438–441.

- Mary Kay Vaughan, "Education: 1889–1940" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 441–445.

- Valentina Torres Septién, "Education: 1940–1996" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 445–449.

- Kuznetsov, Yevgeny N.; Dahlman, Carl J. (2008). Mexico's Transition to a Knowledge-Based Economy: Challenges and Opportunities. World Bank Publications. p. 63. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-6921-0. ISBN 978-0-8213-6921-0.

- United States

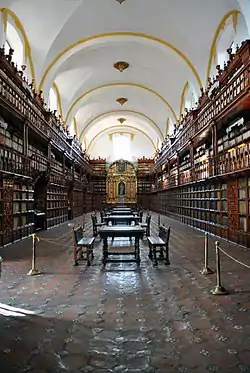

- Brescia, Michael M. (July 2004). "Liturgical Expressions of Episcopal Power: Juan de Palafox y Mendoza and Tridentine Reform in Colonial Mexico". The Catholic Historical Review. 90 (3): 497–518. doi:10.1353/cat.2004.0116. JSTOR 25026636.

- Sherman, William H. (2010). "Palafoxiana, Biblioteca". In Suarez, Michael F.; Woudhuysen, H. R. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Book. Oxford University Press.

- "Biblioteca Palafoxiana" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. (1993). Ley General de Educación retrieved August 10, 2018), from http://www.sep.gob.mx/work/models/sep1/Resource/b490561c-5c33-4254-ad1caad33765928a/07104.pdf

- Fletcher, T., Dejud, C., Klingler, C., & Lopez-Marisca, I. (2003) The changing paradigm of special education in Mexico: Voices from the field. Bilingual Research Journal, 27(3), 409–430.

- Flores Barrera, V.J., & García Cedillo, I. (2016) Apoyos que reciben estudiantes de secundaria con discapacidad en escuelas regulares: ¿Corresponden a lo que dicen las leyes? Revista Educación, 40(2), 1–20.

- Forlin, C., García-Cedillo, I., Romero‐Contreras, S., Fletcher, T., & Rodríguez-Hernández, H.J., (2010) Inclusion in Mexico: ensuring supportive attitudes by newly graduated teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(7), 723–739.

- Romero-Contreras, S., Garcia-Cedillo, I., Forli, C., & Lomelí-Hernández, K.A., (2013) Preparing teachers for inclusion in Mexico: How effective is this process? Journal of Education for Teaching, 39(5), 509–522.

- Rama, A. (2011, April 13). “Factbox: Facts about Mexico's education system.” Retrieved November 17, 2014, from https://www.reuters.com/article/2011/04/13/us-mexico-education-factbox-idUSTRE73C4UY20110413!

- "Low-Performing Students: Why They Fall Behind and How to Help Them Succeed Country note Mexico” Retrieved June 16, 2016, from http://www.oecd.org/mexico/PISA-2012-low-performers-Mexico-ENG.pdf

- "Mexico's Peña Nieto enacts major education reform". BBC. 26 February 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

The law foresees a centralised process for hiring, evaluating, promoting and retaining teachers.

- "Mexico union head Gordillo charged with organised crime". BBC. 28 February 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Juan Montes (June 12, 2016). "Mexico Detains Leader of Dissident Teachers Group in Oaxaca State Rubén Núñez arrested on charges of using illegally obtained funds, Attorney General's Office says". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Kuznetsov & Dahlman 2008, p. 72.

- Kuznetsov & Dahlman 2008, p. 81.

- Tamez Guerra, Reyes; Rubio Oca, Julio; Fuentes Lemus, Bulmaro; Valdés Garza, Mario (May 2005). Disposiciones para la Operación de Estudios de Posgrado en el Sistema Nacional de Educación Superior Tecnológica (in Spanish). Mexico: Dirección General de Educación Superior Tecnológica.

- Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good? (PDF). UNESCO. 2015. p. 47. ISBN 978-92-3-100088-1.

- "Home - International School Consultancy". www.iscresearch.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-07-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The new local". The Economist.

- De Borhegyi, Stephan F. (1966). "The Wind God's Breastplate". Expedition. Vol. 8 no. 4.

This breastplate, the insignia of the wind god, called in Nahuatl the ehecailacacozcatl, (the 'spirally voluted wind jewel') was made by cutting across the upper portion of a marine conch shell, and drilling holes for suspension by a cord. Such conch shell breastplates were either hung on the sculpture of the god himself or were worn by the high priests, the earthly representatives of this god. According to such sixteenth century Spanish authorities as Fray Bernardino de Sahagun, [...] the title of Quetzalcoatl was reserved for the high priests or pontiffs among the Aztecs and other inhabitants of Mexico. Only they were entitled to wear the emblem of ehecailacacozcatl, the insignia of this god. Such marine shell breastplates are therefore extremely rare. Of the few that survived the Spanish Conquest, most were destroyed by zealous friars; only a handful have been turned up by archaeologists.

- Pilar Gonzalbo Aizpuru, “Education: Colonial” in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 435.

- Aizpuru, “Education: Colonial,” p. 435.

- Karttunen, Frances. “Nahuatl Literacy” in The Inca and Aztec States, New York: Academic Press,

- Lockhart, James The Nahuas After the Conquest. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1992.

- Martha Eugenia Rodríguez, “Escuela Nacional de Medicina,” in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 458.

- Aizpuru, “Education: Colonial,” p. 436.

- Lino Gómez Canedo, La educación de los marginados durante la época colonial,"cap. III. "Casas de recogimiento y de educación para niñas indias," Mexico: Porrúa 1982.

- Aizpuru, “Education: Colonial,” p. 437.

- Aizpuru, “Education: Colonial,” p. 438.

- Victoria Andrade de Herrara, "Education in Mexico: Historical and Contemporary Educational Systems" in Children of La Frontera: Binational Efforts to Serve Mexican Migrant and Immigrant Students, Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC), 1996, p. 26.

- Andrade de Herrara, "Education in Mexico", p. 27

- Andrade de Herrara, "Education in Mexico", p. 27.

- Charles A. Hale, The Transformation of Liberalism in Late Nineteenth-Century Mexico. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1989, p. 140.

- Albert Delmez, "The Positivist Philosophy in Mexican Education, 1867–1873," The Americas vol. 6, no. 1.

- Hale, The Transformation of Liberalism, p. 144.

- Vaughan, Mary Kay, The State, Education, and Social Class in Mexico, 1880–1928. DeKalb IL: Northern Illinois University Press 1982, pp. 74–77

- Mary Kay Vaughan, "Nationalizing the Countryside: Schools and Communities in the 1930s" in The Eagle and the Virgin: Nation and Cultural Revolution in Mexico, 1920–1940, Vaughan, Mary Kay and Stephen E. Lewis, eds. Durham: Duke University Press 2006, p. 158

- Vaughan, State, Education, and Social Class in Mexico, p. 76-77

- Miller, Francesca, "Feminism and Feminist Organizations" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 2, p. 550. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Lewis, Stephen E. "The Nation, Education, and the 'Indian Problem' in Mexico, 1920–1940" in The Eagle and the Virgin: Nation and Cultural Revolution in Mexico, 1920–1940, Mary Kay Vaughan and Stephen E. Lewis, eds. Durham: Duke University Press 2006, p. 180.

- "Health Care in Mexico". Expatforum.com. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- Vaughan, "Nationalizing the Countryside" pp. 158–59

- Agren, David (December 10, 2012). "'Normalistas' fight changes in Mexico education system". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 4A.

- Vaughan, "Nationalizing the Countryside" p. 159.

- Alberto Bremauntz, La educación socialista en México. Mexico City: Imprenta Rivadeneyra 1943, p. 166.

- Espinosa, David. Jesuit Student Groups, the Universidad Iberoamericana, and Political Resistance in Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2014.

- Valentina Torres Septién, "Education: 1940–1996" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 446.

- Torres Septién, "Education: 1940–1996" pp. 446–47.

- Gabriela Soto Laveaga, "'Let's become fewer': Soap operas, contraception, and nationalizing the Mexican family in an overpopulated world." Sexuality Research and Social Policy September 2007, vol. 4 no. 3.

- Torres Septién, "Education: 1940–1996" pp. 448–48

- Gritos y susurros: Experiencias intempestivas de 38 mujeres.

- Lorey, David E. "Education and the challenges of Mexican development." Challenge 38.2 (1995): 51–55.

- Dennis Gilbert, "Rewriting History: Salinas, Zedillo and the 1992 Textbook Controversy", Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, Vol. 13 No. 2, Summer, 1997; (pp. 271–297) DOI: 10.2307/1052017

- Hecock, R. Douglas. "Democratization, education reform, and the Mexican Teachers' Union." Latin American Research Review 49.1 (2014): 62–82.

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-21597680 accessed 1 March 2019.

- Cook, Maria. Organizing Dissent: Unions, the State, and the Democratic Teachers’ Movement in Mexico. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press 1996.

- Grindle, Merilee S. Despite the Odds: The Contentious Politics of Education Reform. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 2004.

- Rama, A. (2011, April 13). “Factbox: Facts about Mexico's education system.” Retrieved November 17, 2014, from https://www.reuters.com/article/2011/04/13/us- mexico-education-factbox-idUSTRE73C4UY20110413!

- Francisco Alba, The Population of Mexico: Trends, Issues, and Policies (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1982), 52.

- "Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Estados Unidos Mexicanos" (PDF). INEGI. pp. 28–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "INEGI literacy report −14, 2005". Inegi.gob.mx. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- "INEGI literacy report 15+, 2005". Inegi.gob.mx. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- "Mexico: Youth Literacy Rate". Global Virtual University. Archived from the original on July 19, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- Art in free textbooks https://www.gob.mx/cultura/articulos/el-arte-en-los-libros-de-texto-gratuitos?idiom=es accessed 3 March 2019.

- "Nombran al Tec de Monterrey como la mejor universidad privada de México". Telediario CDMX (in Spanish). 2019-06-19. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- "Recruiter's scoreboard Highlights" (PDF). The Wall Street Journal/Harris Interactive survey of corporate recruiters on business schools. Retrieved October 4, 2007.

ABOUT >

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 License statement/permission on Wikimedia Commons. Text taken from Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good?, 47, UNESCO. UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 License statement/permission on Wikimedia Commons. Text taken from Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good?, 47, UNESCO. UNESCO.

Sources

- Tamez Guerra, Reyes (2004). Sistema Educativo de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Principales cifras, ciclo escolar 2003–2004 (PDF). Mexico City: Dirección General de Planeación, Programación y Presupuesto Secretaría de Educación Pública. ISBN 968-5778-12-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-01-10.

- Department of State (2004). International Religious Freedom Report 2004. Mexico. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- US Department of Education (2003) Education around the World: Mexico.

Further reading

History, Colonial era

- Aizpuru, Pilar Gonzalbo, "Education: Colonial" in Encyclopedia or Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 434–438.

- Becerra López, José Luis. La organización de los estudios en la Nueva España. Mexico City: Cultura, 1963.

- Gómez Canedo, Lino. La educación de los marginados durante la època colonial. Mexico City: Porrúa 1982.

- Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Pilar. "Education: Colonial" in Encyclopedia or Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 434–438.

- Kobayashi, José María. La educación como conquista. Mexico City: El Colegio de México 1990.

- Larroyo, Francisco. Historia comparada de la educacíon in México. Mexico City: Porrúa 1962.

- Luque Alcaide, Elisa. La educación en Nueva España en el siglo XVIII. Seville: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas 1970.

- Plaza y Jaén, Bernardo de la. Crónica de la Real y Pontificia Universidad de México escrita en el siglo XVIII. 2 vols. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1931.

- Ramìrez, Tàmmas. Creo en los impactos de la revolución mexicana hacia nuestro sistema escolar-Chilpancingo: Guerrero, 1972.

- Rodríguez, Martha Eugenia. "Escuela Nacional de Medicina" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 458–461.

- Tanck de Estrada, Dorothy. La educación ilustrada (1786–1836). Mexico City: El Colegio de México 1977.

- Vázquez, Josefina Zoraida., et al. Ensayos sobre la historia de la educación en México. Mexico City: El Colegio de México 1981.

History, Post-independence period

- Bazant, Milada. Historia de la educación en el Porfiriato. Mexico City: El Colegio de México 1993.

- Benjamin, Thomas. La Revolución: Mexico's Great Revolution in Memory, Myth, and History. Austin: University of Texas Press 2000.

- Britton, John A. Educación y radicalismo en México. 2 vols. Mexico City: SEP-Setentas 1976.

- Chowning, Margaret. "Culture Wars in the Trenches? Public Schools and Catholic Education in Mexico, 1867–1897". Hispanic American Historical Review 97:4 (Nov. 2017), pp. 613–650.

- Cook, Maria. Organizing Dissent: Unions, the State, and the Democratic Teachers’ Movement in Mexico. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press 1996.

- Escobar Ohmstede, Antonio. "Education: 1821–1989" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 438–441.

- Espinosa, David. Jesuit Student Groups, the Universidad Iberoamericana, and Political Resistance in Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2014.

- "Flunking the test: Failing schools pose a big challenge to President Enrique Peña Nieto's vision for modernising Mexico." The Economist, March 7, 2015, pp. 35–36.

- Foweraker, Joe. Popular Mobilization in Mexico: The Teachers’ Movement, 1977–87. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1992.

- Gilbert, Dennis. "Rewriting History: Salinas, Zedillo and the 1992 Textbook Controversy". Mexican Studies/Esudios Mexicanos 13(2)Summer 1997.

- Grindle, Merilee S. Despite the Odds: The Contentious Politics of Education Reform. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 2004.

- Hecock, R. Douglas. "Democratization, education reform, and the Mexican Teachers' Union." Latin American Research Review 49.1 (2014): 62–82.

- INEE (Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación). La calidad de la educación básica en México, 2004. Mexico City: INEE 2004

- Knight, Alan, "Popular Culture and the Revolutionary State in Mexico, 1910–1940," Hispanic American Historical Review 74:3(1994).

- Lopez-Acevedo, Gladys. “Professional Development and Incentives for Teacher Performance in Schools in Mexico.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3236. Washington, DC: World Bank 2004.

- Lorey, David E. "Education and the challenges of Mexican development." Challenge 38.2 (1995): 51–55.

- Mabry, Donald J. The Mexican University and the State: Student Conflicts, 1910–1971. College Station, Texas: Texas A & M University Press 1982.

- McGinn, Noel, and Susan Street. "Has Mexican Education Generated Human or Political Capital?." Comparative Education 20.3 (1984): 323–338.

- Meneses Morales, Ernesto, et al. Tendencias educativas oficiales en México, 1911–1934. Mexico City: Centro de Estudios Educativos, Universidad Iberoamericana 1986.

- Meneses Morales, Ernesto, et al. Tendencias educativas oficiales en México,1934–1964. Mexico City: Centro de Estudios Educativos, Universidad Iberoamericana 1988.

- Meneses Morales, Ernesto. La Universidad Iberoamericana en el Contexto de la Educación Superior Contemporanea. Mexico City: UIA 1979.

- O'Malley, Irene V. The Myth of the Mexican Revolution: Hero Cults and the Institutionalization of the Mexican State. New York: Greeenwood Press 1986.

- Ornelas, Carlos. “The Politics of Privatisation, Decentralisation and Education Reform in Mexico.” International Review of Education 50 (3–4), 2004: 397–418

- Raby, David L. Educación y revolución social en Mèxico. Mexico City: SEP-Setentas 1976.

- Rincón-Gallardo, Santiago. "Large scale pedagogical transformation as widespread cultural change in Mexican public schools." Journal of Educational Change 17.4 (2016): 411–436.

- Rodríguez, Martha Eugenia. "Escuela Nacional de Medicina" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 458–461.

- Ruiz, Ramón Eduardo. Mexico: The Challenge of Poverty and Illiteracy. San Marino CA: Huntington Library 1963.

- Secretaría de Educación Pública. Primer Congreso Nacional de Instrucción, 1889–1928. Mexico City: SEP 1975.

- Street, Susan. “El SNTE y la política educativa, 1970–1990.” Revista Mexicana de Sociología 54 (2)1992: 45–72.

- Tatto, María Teresa. "Improving teacher education in rural Mexico: The challenges and tensions of constructivist reform." Teaching and teacher education 15.1 (1999): 15–35.

- Torres Septién, Valentina. "Education: 1940–1996" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 445–449.

- Vaughan, Mary Kay. The State, Education and Social Class in Mexico, 1880–1928. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press 1982.

- Vaughan, Mary Kay. "Primary Education and Literacy in Nineteenth-Century Mexico: Research Trends, 1968–1988". Latin American Research Review 24(3)(1990).

- Vaughan, Mary Kay. The State, Education, and Social Class in Mexico, 1880–1928. DeKalb IL: Northern Illinois University Press 1982.

- Vaughan, Mary Kay. Cultural Politics in Revolution: Peasants, Teachers, and Schools in Mexico, 1930–1940. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 1997.

- Vaughan, Mary Kay. "Education: 1889–1940" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 441–445.

- Vázquez, Josefina Zoraida. Nacionalismo y educación en México. Mexico City: El Colegio de México 1970.

- Villa Lever, Lorenza. Los libros de texto gratuitos: La disputa por la educación en México. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara 1988.

- World Bank, "PROGRAM DOCUMENT FOR A PROPOSED LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$300,751,879.70 TO THE UNITED MEXICAN STATES FOR A SECOND UPPER SECONDARY EDUCATION DEVELOPMENT POLICY LOAN", International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, February 8, 2012

External links

- OECD Education Policy Outlook: Mexico

- (in Spanish) SEP homepage

- Information on education in Mexico, OECD – Contains indicators and information about Mexico and how it compares to other OECD and non-OECD countries

- Diagram of Mexican education system, OECD – Using 1997 ISCED classification of programmes and typical ages. Also in Spanish

.svg.png.webp)