History of science and technology in Mexico

The history of science and technology in Mexico spans many years. Ancient Mexican civilizations developed mathematics, astronomy, and calendrics, and solved technological problems of water management for agriculture and flood control in Central Mexico. Following the Spanish conquest in 1521, New Spain (colonial Mexico) was brought into the European sphere of science and technology. The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico, established in 1551, was a hub of intellectual and religious development in colonial Mexico for over a century. During the Spanish American Enlightenment in Mexico, the colony made considerable progress in science, but following the war of independence and political instability in the early nineteenth century, progress stalled. During the late 19th century under the regime of Porfirio Díaz, the process of industrialization began in Mexico. Following the Mexican Revolution, a ten-year civil war, Mexico made significant progress in science and technology. During the 20th century, new universities, such as the National Polytechnical Institute, Monterrey Institute of Technology and research institutes, such as those at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, were established in Mexico.

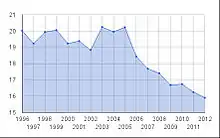

According to the World Bank, Mexico is Latin America's largest exporter of high-technology goods (High-technology exports are manufactured goods that involve high R&D intensity, such as in aerospace, computers, pharmaceuticals, scientific instruments, and electrical machinery) with $40.7 billion worth of high-technology goods exports in 2012.[1] Mexican high-technology exports accounted for 17% of all manufactured goods in the country in 2012 according to the World Bank.[2]

Early history of science in Mexico

The Olmec, a Pre-Columbian civilization living in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, calendar system required an advanced understanding of mathematics. The Olmec number system was based on 20 instead of decimal and used three symbols- a dot for one, a bar for five, and a shell-like symbol for zero. The concept of zero is one of the Olmecs' greatest achievements. It permitted numbers to be written by position and allowed for complex calculations. Although the invention of zero is often attributed to the Mayans, it was originally conceived by the Olmecs.

To predict planting and harvesting times, early peoples studied the movements of the sun, stars, and planets. They used this information to make calendars. The Aztecs created two calendars- one for farming, and one for religion. The farming calendar let them know when to plant and to harvest crops. An Aztec calendar stone dug up in Mexico City in 1790 includes information about the months of the year and pictures of the sun god at the center.

After the Viceroyalty of New Spain was founded, the Spanish brought the scientific culture that dominated Spain to the Viceroyalty of New Spain.[3]

The Franciscan order founded the first school of higher learning in the Americas, the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco in 1536, at the site of an Aztec school.[4]

The municipal government (cabildo) of Mexico City formally requested the Spanish crown to establish a university in 1539.[5] The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico (Real y Pontificia Universidad de México) was established in 1551. The university was administered by the clergy and it was the official university of the empire. It provided quality education for the people, and it was a hub of intellectual and religious development in the region. It taught subjects such as physics and mathematics from the perspective of Aristotelian philosophy. Augustinian philosopher Alonso Gutiérrez in 1553 he became the first professor of the University of Mexico. He wrote Physical speculation, the first scientific text in the Americas, in 1557. By the late 18th century, the university had trained 1,162 doctors, 29,882 bachelors, and many lawyers.[3]

Educated by the Jesuits in Mexico Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora displayed an astonishing proficiency in science and mathematics. During the late 17th century he won the chair of mathematics and astronomy at the University of Mexico. Sigüenza challenged the official doctrine that comets were divine portents of disaster and argued for their natural origin. He is considered the first scientist of colonial Mexico to question the scholasticism that permeated the university and most of society.

Science during the Mexican Enlightenment

_retrato.png.webp)

During the Mexican Enlightenment, science can be divided into four periods: the early period (from 1735 to 1767), the Creole period (from 1768 to 1788), the official or Spanish period (from 1789 to 1803), and the period of synthesis (from 1804 to the beginning of the Mexican independence movement in 1810).[6]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, modern science developed in Europe but it lagged behind in Mexico. The new ideas developed in science in Europe were not important in Mexico.[7] The 1767 expulsion of Jesuits, who had introduced the new ideas in Mexico, helped to antagonize the Creoles and also promoted national feelings among Mexicans.[6][8] After the expulsion, self-taught Creoles were the first scientists in Mexico. Later on, they were joined by the Spanish scientists, and they did research, teaching, publishing, and translating texts. The ideas of Francis Bacon and René Descartes were freely discussed at seminars, which caused scholasticism to lose strength. During the Mexican Enlightenment, Mexico made progress in science. Progress was made in subjects such as astronomy, engineering, etc. In 1792 the Seminary of Mining was established. Later it became the College of Mining, in which the first modern physics laboratory in Mexico was established.[6]

Famous scientists of the Enlightenment included José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez and Andrés Manuel del Río.[6] Río discovered the chemical element vanadium in 1801.[9]

Science after the Mexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence brought an end to Mexico's scientific progress. The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico closed in 1833. For many years, there were no scientific activities in Mexico.[6] The Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico was definitively shut down in 1865.[10]

During the end of the nineteenth century, the process of industrialization began in Mexico. Under the influence of positivists and scientific thinkers, the government-assisted in public education. In 1867 Gabino Barreda, a student of Auguste Comte, was charged with the commission aimed at reforming education. Subjects such as physics, chemistry, and mathematics were included in the secondary school curriculum. National Preparatory School was established. The influence of positivists led to a renaissance of scientific activity in Mexico.[11]

General Manuel Mondragon invented the Mondragón rifle during this time. These designs include the straight-pull bolt-action M1893 and M1894 rifles, and Mexico's first self-loading rifle, the M1908 - the first of the designs to see combat use.

Science and technology in the 20th Century

During the 20th century, Mexico made significant progress in science and technology. New universities and research institutes were established. The National Autonomous University of Mexico (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM) was officially established in 1910,[12] and the university become one of the most important institutes of higher learning in Mexico.[10] UNAM provides world-class education in science, medicine, and engineering.[13] Many scientific institutes and new institutes of higher learning, such as National Polytechnic Institute (founded in 1936),[14] were established during the first half of the 20th century. Most of the new research institutes were created within UNAM. Twelve institutes were integrated into UNAM from 1929 to 1973.[15]

Mexican scientists, physicians, and intellectuals were involved in the movement to shape Mexico's population through eugenics. The Sociedad Mexicana de Eugenesia was founded in 1931, and was concerned with mental retardation, prison reform, tuberculosis, syphilis, alcoholism, sexual education, mestizaje, prostitution, puericulture, (scientific child-rearing), and single mothers. The society advocated for maternal assistance, eradication of juvenile delinquency, and incorporation of its ideas into the functioning of schools, prisons, and public health administration. It succeeding in having established a medical clinic, the Hereditary Health Counseling Center, for workers.[16] The organization published the journal Eugenesia until 1954.[17]

In the 1930s Manuel Sandoval Vallartaa Mexican physicist worked on Cosmic ray research and in 1943 to 1946, he divided his time between MIT and UNAM as a full-time professor.

On August 31, 1946, Guillermo González Camarena sent his first color transmission from his lab in the offices of The Mexican League of Radio Experiments, at Lucerna St. #1, in Mexico City. The video signal was transmitted at a frequency of 115 MHz. and the audio in the 40-meter band. González Camarena was a Mexican engineer who was the inventor of a color-wheel type of color television, and who also introduced color television to Mexico.

Mexico was in the forefront of the Green Revolution, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and developed by Norman Borlaug, who later won the Nobel Prize for his work. The aim was to increase the productivity of Mexican agriculture through the development of new strains of seeds. Mexico founded the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center to further this scientific work.[18]

In the 1950s, the wild yam known as barbasco was discovered to contain steroid hormones that could affect human fertility and led to the development of The Pill. A Mexican research company, Syntex was founded and began producing oral contraceptives. The Mexican government under President Luis Echeverría created a state-run company, Proquivemex, to control and regulate the industry.[19]

In 1959, the Mexican Academy of Sciences (Academia Mexicana de Ciencias) was established as a non-governmental, non-profit organization of distinguished scientists. The Academy has grown in membership and influence, and it represents a strong voice of scientists from different fields, mainly in science policy.[20]

By 1960, science was institutionalized in Mexico. It was viewed as a legitimate endeavor by the Mexican society.[15]

In 1961, the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute was established as a center for graduate studies in subjects such as biology, mathematics, and physics. In 1961, the institute began its graduate programs in physics and mathematics and schools of science were established in Mexican states of Puebla, San Luis Potosí, Monterrey, Veracruz, and Michoacán. The Academy for Scientific Research was established in 1968 and the National Council of Science and Technology was established in 1971.[15]

Ricardo Miledi, one of the ten most quoted neuro-biologists of all time, was born in Mexico, D.F. in 1927. His career in science began in 1955 when, just before graduating in Medicine at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (UNAM), he joined one of the most active research groups in his country, part of the Instituto Nacional de Cardiología (the National Institute of Cardiology).

Many of Professor Miledi's studies and breakthroughs in Neurobiology, especially those related to the mechanisms of synaptic and neuromuscular transmission, are considered to be classic throughout the world. Over 450 publications are the tangible product of forty years of research devoted to the main to the primary functions of the nervous system: the transmission of information between cells. He has been a member of the Royal Society of London since 1980 and entered the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1986. In 1999 Miledi was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for Technical and Scientific Research. He has been Professor of Biophysics at the University of London and distinguished professor of the University of California since 1984. He also leads a neurobiology laboratory in UNAM in Querétaro, México.[21]

In 1985 Rodolfo Neri Vela became the first Mexican citizen to enter space as part of the STS-61-B mission.[22]

In 1995 Mexican chemist Mario J. Molina shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Paul J. Crutzen, and F. Sherwood Rowland for their work in atmospheric chemistry, particularly concerning the formation and decomposition of ozone.[23] Molina, an alumnus of UNAM, became the first Mexican citizen to win the Nobel Prize in science.[24]

The Large Millimeter Telescope was inaugurated on 22 November 2006. It is the world's largest and most sensitive single-aperture telescope in its frequency range, built for observing radio waves in the wavelengths from approximately 0.85 to 4 mm. Located on top of the Sierra Negra. It is a binational Mexican (70%) - American (30%) joint project.

In 1962, the National Commission of Outer Space (Comisión Nacional del Espacio Exterior, CONNE) was established but was dismantled in 1977. On July 30, 2010, the law to create the Agencia Espacial Mexicana (AEM) was published. It is now in the process of defining the National Space Policy and its program of activities. Robotics is a new area under development in Mexico, the Mexone Robot is one of the most advanced robot designs in the world.[25]

Science and technology in the 21st Century

Austrade predicts Mexico's IT spending will grow at a compound annual growth rate of 11 percent over 2011–2015.[26]

Based on the information managed by Scopus, a bibliographic database for science, the Spanish web portal SCImago places Mexico at 28th in-country scientific ranking with 82,792 publications, and 34th considering its value of 134 for the h-index. Both positions are computed for the period 1996–2007.

The electronics industry of Mexico has grown enormously within the last decade. In 2007 Mexico surpassed South Korea as the second-largest manufacturer of televisions, and in 2008 Mexico surpassed China, South Korea, and Taiwan to become the largest producer of smartphones in the world. There are almost half a million (451,000) students enrolled in electronics engineering programs.

Chicxulub crater

The Chicxulub crater is an impact crater buried underneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. The crater was discovered by Antonio Camargo and Glen Penfield, geophysicists who had been looking for petroleum in the Yucatán during the late 1970s. The Alvarez hypothesis posits that the mass extinction of the dinosaurs and many other living things during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event was caused by the impact of a large asteroid on the Earth. Evidence indicates that the asteroid fell in the Yucatán Peninsula, at Chicxulub, Mexico. The hypothesis is named after the father-and-son team of scientists Luis and Walter Alvarez, who first suggested it in 1980.

Mexican National Prize for Arts and Sciences

Physics, Mathematics, and Natural Sciences

Ciencias Físico-Matemáticas y Naturales

- 2018: (Tie)

- Carlos Alberto Aguilar Salinas

- Mónica Alicia Clapp Jiménez Labora

- 2017: María Elena Álvarez-Buylla Roces

- 2016: (Tie)

- Cecilia Noguez

- David Kershenobich Stalnikowitz

- 2015: (Tie)

- Jorge Alcocer Varela

- Fernando del Río Haza

- 2014: (Tie)

- Carlos Federico Arias Ortiz

- Mauricio Hernández Ávila

- 2013: (Tie)

- Federico Bermúdez Rattoni

- Magdaleno Medina Noyola

- 2012: (Tie)

- Ruben Gerardo Barrera

- Carlos Artemio Coello Coello

- Susana Lizano

- 2011:Julio Collado-Vides

- 2010: (Tie)

- Marcelo Lozada y Cassou

- Gerardo Gamba Ayala

- 2009: (Tie)

- Alberto Darszon Israel

- Jaime Urrutia Fucugauchi

- 2008: (Tie)

- Edmundo García Moya

- Alberto Robledo Nieto

- Moisés Selman

- 2007: Silvia Torres Castilleja

- 2006: Juan Ramón de la Fuente

- 1986: Adolfo Martínez Palomo

- 1985: Marcos Rojkind Matluk

- 1984: José Ruiz Herrera

- 1983: Octavio Augusto Novaro

- 1982: Bernardo Sepúlveda Gutiérrez

- 1981: Manuel Peimbert Sierra

- 1980: Guillermo Soberón Acevedo

- 1979: Pablo Rudomín Zevnovaty

- 1978: Rafael Méndez Martínez

- 1977: Jorge Cerbón Solórzano

- 1976: (Tie)

- Ismael Herrera Revilla

- Julían Adem Chahín

- Samuel Gitler Hammer

- 1975:(Tie)

- Arcadio Poveda Ricalde

- Guillermo Massieu Helguera

- Joaquín Gravioto Muñoz

- 1974: (Tie)

- Emilio Rosenblueth Deutsch

- Ruy Pérez Tamayo

- 1973: Carlos Casas Campillo

- 1972: (Tie)

- Antonio González Ochoa

- Isaac Costero Tudanca

- Luis Sánchez Medal

- 1971: Jesús Romo Armería

- 1970: Carlos Graef Fernández

- 1969: (Tie)

- Fernando de Alba Andrade

- Ignacio Bernal

- 1968: Salvador Zubirán Anchondo

- 1967: José Adem Chaín

- 1966: Arturo Rosenblueth Stearns

- 1964: Ignacio González Guzmán

- 1963: Guillermo Haro Barraza

- 1961: Ignacio Chávez Sánchez

- 1959: Manuel Sandoval Vallarta

- 1957: Nabor Carrillo Flores

- 1948: Maximiliano Ruiz Castañeda

Technology and Design

Tecnología y Diseño

- 2018: (Tie)

- Ricardo Chicurel Uziel

- Leticia Myriam Torres Guerra

- 2017:Emilio Sacristan Rock

- 2016: (Tie)

- Lourival Possani Postay

- Luis Enrique Sucar Succar

- 2015:

- Raúl Rojas

- Enrique Galindo Fentanes

- 2014: José Mauricio López Romero

- 2013: Martín Ramón Aluja Schuneman Hofer

- 2012: Sergio Antonio Estrada Parra

- 2011: Raúl Gerardo Quintero Flores

- 2010: Sergio Revah Moiseev

- 2009: (Tie)

- Blanca Elena Jiménez Cisneros

- José Luis Leyva Montiel

- 2008: María de los Ángeles Valdés

- 2007: Miguel Pedro Romo Organista

- 2006: Fernando Samaniego Verduzco

- 2005: Alejandro Alagón Cano

- 2004: (Tie)

- Héctor Mario Gómez Galvarriata

- Martín Guillermo Hernández Luna

- Arturo Menchaca

- 2003: Octavio Manero Brito

- 2002: Alexander Balankin

- 2001: Filberto Vázquez Dávila

- 2000: Francisco Alfonso Larque Saavedra

- 1999: Jesús Gonzales Hernández

- 1997: (Tie)

- Baltasar Mena Iniesta

- Feliciano Sánchez Silencio

- 1996: (Tie)

- Adolfo Guzmán Arenas

- María Luisa Ortega Delgado

- 1995: Alfredo Sánchez Marroquín

- 1994: (Tie)

- Francisco Sánchez Sesma

- Juan Vázquez Lomberta

- 1993: José Ricardo Gómez Romero

- 1992: (Tie)

- Lorenzo Martínez Gómez

- Gabriel Torres Villaseñor

- 1991: (Tie)

- Octavio Paredes López

- Roberto Meli Piralla

- 1990: (Tie)

- Daniel Reséndiz Núñez

- Juan Milton Garduño

- 1988: Mayra de la Torre

- 1987: Enrique Hong Chong

- 1986: Daniel Malacara Hernández

- 1985: José Luis Sánchez Bribiesca

- 1984: Jorge Suárez Díaz

- 1983: José Antonio Ruiz de la Herrán Villagómez

- 1982: Raúl J. Marsal Córdoba

- 1981: Luis Esteva Maraboto

- 1980: Marcos Mazari Menzer

- 1979: Juan Celada Salmón

- 1978: Enrique del Moral

- 1977: Francisco Rafael del Valle Canseco

- 1976: (Tie)

- Reinaldo Pérez Rayón

- Wenceslao X. López Martín del Campo

Mexican-born scientists working in the United States

.JPG.webp)

Héctor García-Molina a Mexican-American computer scientist and Professor in the Departments of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering at Stanford University was advisor to Sergey Brin, the co-founder of Google, from 1993 to 1997 when he was a computer science student at Stanford. In March 2015, Mexican-born engineer Luis Velasco, who works at NASA, designs and engineers robots for the company. He obtained a scholarship at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah and studied mechanical engineering. Details of a mousepad designed by Armando M. Fernandez were published in the Xerox Disclosure Journal in 1979.

- Alvarez - Gonzalez Rafael - (molecular biologist)

- Albert Vinicio Bae - (physicist, Science educator)

- Rodrigo Banuelos - (mathematician)

- Barona, Andres, Jr. - (educational psychologist)

- Diaz, Fernando G. - (neurosurgeon)

- Garcia, Hector P. - (physician, activist)

- Garcia - Luna - Aceves J.J. (electrical engineer, inventor)

- Arturo Gómez-Pompa (botanist)

- Gonzalez, Elma (cell biologist)

Premio México de Ciencia y Tecnología

Premio México de Ciencia y Tecnología is an award bestowed in by the CONACYT to Ibero-American (Latin America plus the Iberian Peninsula) scholars in recognition of advances in science and/or technology.

See also

Further reading

- Agostini, Claudia. Monuments of Progress: Modernization and Public Health in Mexico City, 1876–1910.University of Calgary Press and University Press of Colorado 2003.

- Beatty, Edward. Technology and the Search for Progress in Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press 2015.

- Boyer, Christopher R., ed. A Land Between Waters: Environmental Histories of Modern Mexico. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 2012.

- Cotter, Joseph. Troubled Harvest: Agronomy and Revolution in Mexico, 1880-2002. Westport CT: Praeger 2003.

- Fishburn, Evelyn and Eduardo L. Ortiz, eds., Science and the Creative Imagination in Latin America. London: Institute for the Study of the Americas 2005.

- Fortes, Jacqueline; Larissa Adler Lomnitz. Becoming A Scientist In Mexico. Penn State University Press 1990. ISBN 0-271-02632-4

- Hewitt de Alcántara, Cynthia. Modernizing Mexican Agriculture: Socioeconomic Implications of Technological Change, 19401970. Geneva: UN Research Institute for Social Development 1976.

- Levy, Daniel C. (1986). Higher Education and the State in Latin America: Private Challenges to Public Dominance. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-47608-1.

- Medina Eden, et al., eds. Beyond Imported Magic: Essays on Science, Technology, and Society in Latin America. Cambridge MA: MIT Press 2014.

- Simonian, Lane. Defending the Land of the Jaguar: A History of Conservationism in Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press 1995.

- Saldaña, Juan José. Science in Latin America: A History. Austin: University of Texas Press 2006.

- Soto Laveaga, Gabriela. Jungle Laboratories: Mexican Peasants, National Projects, and the Making of The Pill. Durham: Duke University Press, 2009.

- Soto Laveaga, Gabriela. "Bringing the Revolution to Medical Schools: Social Service and a Rural Health Emphasis in 1930s Mexico." Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 29, no. 2 (2013): 397–427.

- Trabulse, Elías (1983). Historia de la ciencia en México: Estudios y textos. Siglo XIX. Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-1472-0.

- Trabulse, Elías (1983). Historia de la ciencia en México (versión abreviada). Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Trabulse, Elías (1983–1989). Historia de la ciencia en México (5 vol.). Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Trabulse, Elías (1992). José María Velasco: Un pasaje de la ciencia en México. Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura.

- Trabulse, Elías (1993). Ciencia mexicana: Estudios históricos. Textos Dispersos.

- Trabulse, Elías (1994). Los orígenes de la ciencia moderna en México. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Trabulse, Elías (1995). Arte y ciencia en la historia de México. Fomento Cultural Banamex.

- Wolfe, Mikael D. Watering the Revolution: An Environmental and Technological History of Agrarian Reform in Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press 2017.

References

- "High-technology exports (current US$) - Data". data.worldbank.org.

- "High-technology exports (% of manufactured exports) - Data". data.worldbank.org.

- Fortes & Lomnitz (1990), p. 13

- Where Is the Oldest University in the New World? Donald D. Brand. New Mexico Anthropologist Vol. 4, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 1940), pp. 61-63

- Levy (1986), p. 116

- Fortes & Lomnitz (1990), p. 15

- Fortes & Lomnitz (1990), pp. 13–4

- Fortes & Lomnitz (1990), p. 14

- Cintas, Pedro (2004). "The Road to Chemical Names and Eponyms: Discovery, Priority, and Credit". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 43 (44): 5888–94. doi:10.1002/anie.200330074. PMID 15376297.

- Summerfield, Devine & Levi (1998), p. 285

- Fortes & Lomnitz (1990), p. 16

- Coerver, Pasztor & Buffington (2004), p. 161

- Summerfield, Devine & Levi (1998), p. 286

- Forest & Altbach (2006), p. 882

- Fortes & Lomnitz (1990), p. 18

- Alexandra Minna Stern, "Responsible Mothers and Normal Children: Eugenics, Nationalism, and Welfare in Post-revolutionary Mexico, 1920-1940." Journal of Historical Sociology vol. 12, no. 4, Dec. 1999, pp. 369, 387.

- Stern, "Responsible Mothers" p. 387.

- Joseph Cotter, Troubled Harvest: Agronomy and Revolution in Mexico, 1880–2002, Westport, CT: Praeger. Contributions in Latin American Studies, no. 22, 2003

- Gabriela Soto Laveaga, Jungle Laboratories: Mexican Peasants, National Projects and the Making of the Pill. Duke University. 2009

- "Mexico: Academia Mexicana de Ciencias". International Council for Science. Archived from the original on 2008-11-14. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- Tecnologías, Developed with web control CMS by Intermark. "The Princess of Asturias Foundation". www.fpa.es.

- "Human space flight: A record of achievement, 1961-1998". NASA. Archived from the original on 2004-11-17. Retrieved 2009-04-28.

- "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- Thomson, Elizabeth A. (18 October 1995). "Molina wins Nobel Prize for ozone work". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- "Científicos Mexicanos presentan el robot Mexone". 14 July 2010.

- "Information and communications technology in Mexico". Report. Austrade. Retrieved 14 June 2011.(subscription required)

- Fulghieri, Carl; Bloom, Sharon (2014). "Sarah Elizabeth Stewart". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (5): 893–895. doi:10.3201/eid2005.131876. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 4012821.