Empire style

The Empire style (French pronunciation: [ɑ̃.piːʁ], style Empire) is an early-nineteenth-century design movement in architecture, furniture, other decorative arts, and the visual arts, representing the second phase of Neoclassicism. It flourished between 1800 and 1815 during the Consulate and the First French Empire periods, although its life span lasted until the late-1820s. From France it spread into much of Europe and the United States.

The style originated in and takes its name from the rule of the Emperor Napoleon I in the First French Empire, when it was intended to idealize Napoleon's leadership and the French state. The previous fashionable style in France had been the Directoire style, a more austere and minimalist form of Neoclassicism, that replaced the Louis XVI style. The Empire style brought a full return to ostentatious richness. The style corresponds somewhat to the Biedermeier style in the German-speaking lands, Federal style in the United States, and the Regency style in Britain.

History

The style developed and elaborated the Directoire style of the immediately preceding period, which aimed at a simpler, but still elegant evocation of the virtues of the Ancient Roman Republic:

The stoic virtues of Republican Rome were upheld as standards not merely for the arts but also for political behaviour and private morality. Conventionels saw themselves as antique heroes. Children were named after Brutus, Solon and Lycurgus. The festivals of the Revolution were staged by David as antique rituals. Even the chairs in which the committee of Salut Publique sat were made on antique models devised by David. ...In fact Neo-classicism became fashionable.[1]

The Empire style "turned to the florid opulence of Imperial Rome. The abstemious severity of Doric was replaced by Corinthian richness and splendour".[2]

Two French architects, Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine, were together the creators of the French Empire style. The two had studied in Rome and in the 1790s became leading furniture designers in Paris, where they received many commissions from Napoleon and other statesmen.[3]

Architecture of the Empire style was based on elements of the Roman Empire and its many archaeological treasures, which had been rediscovered starting in the eighteenth century. The preceding Louis XVI and Directoire styles employed straighter, simpler designs compared to the Rococo style of the eighteenth century. Empire designs strongly influenced the contemporary American Federal style (such as design of the United States Capitol building), and both were forms of propaganda through architecture. It was a style of the people, not ostentatious but sober and evenly balanced. The style was considered to have "liberated" and "enlightened" architecture just as Napoleon "liberated" the peoples of Europe with his Napoleonic Code.

The Empire period was popularized by the inventive designs of Percier and Fontaine, Napoleon's architects for Malmaison. The designs drew for inspiration on symbols and ornaments borrowed from the glorious ancient Greek and Roman empires. Buildings typically had simple timber frames and box-like constructions, veneered in expensive mahogany imported from the colonies. Biedermeier furniture also used ebony details, originally due to financial constraints. Ormolu details (gilded bronze furniture mounts and embellishments) displayed a high level of craftsmanship.

General Bernadotte, later to become King Karl Johan of Sweden and Norway, introduced the Napoleonic style to Sweden, where it became known under his own name. The Karl Johan style remained popular in Scandinavia even as the Empire style disappeared from other parts of Europe. France paid some of its debts to Sweden in ormolu bronzes instead of money, leading to a vogue for crystal chandeliers with bronze from France and crystal from Sweden.

After Napoleon lost power, the Empire style continued to be in favour for many decades, with minor adaptations. There was a revival of the style in the last half of the nineteenth century in France, again at the beginning of the twentieth century, and again in the 1980s.

The style survived in Italy longer than in most of Europe, partly because of its Imperial Roman associations, partly because it was revived as a national style of architecture following the unification of Italy in 1870. Mario Praz wrote about this style as the Italian Empire. In the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States, the Empire style was adapted to local conditions and gradually acquired further expression as the Egyptian Revival, Greek Revival, Biedermeier style, Regency style, and late-Federal style.

Ornaments

All Empire ornament is governed by a rigorous spirit of symmetry reminiscent of the Louis XIV style. Generally, the motifs on a piece's right and left sides correspond to one another in every detail; when they don't, the individual motifs themselves are entirely symmetrical in composition: antique heads with identical tresses falling onto each shoulder, frontal figures of Victory with symmetrically arrayed tunics, identical rosettes or swans flanking a lock plate, etc. Like Louis XIV, Napoleon had a set of emblems unmistakably associated with his rule, most notably the eagle, the bee, stars, and the initials I (for Imperator) and N (for Napoleon), which were usually inscribed within an imperial laurel crown. Motifs used include: figures of Victory bearing palm branches, Greek dancers, nude and draped women, figures of antique chariots, winged putti, mascarons of Apollo, Hermes and the Gorgon, swans, lions, the heads of oxen, horses and wild beasts, butterflies, claws, winged chimeras, sphinxes, bucrania, sea horses, oak wreaths knotted by thin trailing ribbons, climbing grape vines, poppy rinceaux, rosettes, palm branches, and laurel. There's a lot of Greco-Roman ones: stiff and flat acanthus leaves, palmettes, cornucopias, beads, amphoras, tripods, imbricated disks, caduceuses of Mercury, vases, helmets, burning torches, winged trumpet players, and ancient musical instruments (tubas, rattles and especially lyres). Despite their antique derivation, the fluting and triglyphs so prevalent under Louis XVI are abandoned. Egyptian Revival motifs are especially common at the beginning of the period: scarabs, lotus capitals, winged disks, obelisks, pyramids, figures wearing nemeses, caryatids en gaine supported by bare feet and with women Egyptian headdresses.[4]

Detail of Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel from Paris, with a pair of winged Victories

Detail of Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel from Paris, with a pair of winged Victories_MET_DP106597.jpg.webp)

A chair decorated with various kinds of palmettes

A chair decorated with various kinds of palmettes

Architecture

The most famous Empire-style structures in France are the grand neoclassical Arc de Triomphe of Place de l'Étoile, Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, Vendôme column, and La Madeleine, which were built in Paris to emulate the edifices of the Roman Empire. The style also was used widely in Imperial Russia, where it was used to celebrate the victory over Napoleon in such memorial structures as the General Staff Building, Kazan Cathedral, Alexander Column, and Narva Triumphal Gate. Stalinist architecture is sometimes referred to as Stalin's Empire style.

Interiors have spacious rooms, richly decorated with symmetrically arranged motifs. The walls are decorated with Corinthian pilasters and vertical panels, having at the top a decorative frieze. The panels are covered with monumental paintings, stuccos, or with embroidered silks. The ceilings have light colours and fine ornaments.[5]

Historic sites which present an homogeneous ensemble, examples of the decoration of interiors of the early 19th century are:

- Château de Malmaison in France

- Hôtel de Beauharnais in Paris

- Château de Compiègne in France

- Château de Fontainebleau in France

- Casa del Labrador in Spain

- Royal Palace of Amsterdam in The Netherlands

The Vendôme Column from Paris

The Vendôme Column from Paris The Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel from Paris

The Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel from Paris The Palais Brongniart (1806–1825) from Paris, built by Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart

The Palais Brongniart (1806–1825) from Paris, built by Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart The North facade of the Palais Bourbon, added in 1806–1808, by architect Bernard Poyet

The North facade of the Palais Bourbon, added in 1806–1808, by architect Bernard Poyet The emperor's bedroom, part of the petits appartements de Napoléon, in the Palace of Fontainebleau (France)

The emperor's bedroom, part of the petits appartements de Napoléon, in the Palace of Fontainebleau (France)%252C_palais%252C_salon_Bleu_3.jpg.webp) The Blue Salon of the Château de Compiègne from Compiègne (France)

The Blue Salon of the Château de Compiègne from Compiègne (France) Fireplace mantel from the Salon des dames d'honneur, in Château de Compiègne

Fireplace mantel from the Salon des dames d'honneur, in Château de Compiègne Main staircase at the Château de Compiègne, with a statue of Apollo

Main staircase at the Château de Compiègne, with a statue of Apollo Room for the Empress Joséphine, on the cusp between Directoire style and Empire style, in the Château de Malmaison (France)

Room for the Empress Joséphine, on the cusp between Directoire style and Empire style, in the Château de Malmaison (France).jpg.webp) Empress' bedroom from the Château de Malmaison (France)

Empress' bedroom from the Château de Malmaison (France) Design for a bed alcove, from circa 1805-1810

Design for a bed alcove, from circa 1805-1810 Design of a room, by Charles Percier, from 1812

Design of a room, by Charles Percier, from 1812

Furniture

_MET_DP106594.jpg.webp) Washstand (athénienne or lavabo); 1800–1814; legs, base and shelf of yew wood, gilt-bronze mounts, iron plate beneath shelf; height: 92.4 cm, width: 49.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Washstand (athénienne or lavabo); 1800–1814; legs, base and shelf of yew wood, gilt-bronze mounts, iron plate beneath shelf; height: 92.4 cm, width: 49.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City).jpg.webp) Secretary; circa 1804-1809; amboyna wood veneered on pine, with gilt-bronze mounts; 173.4 x 87.6 x 37.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Secretary; circa 1804-1809; amboyna wood veneered on pine, with gilt-bronze mounts; 173.4 x 87.6 x 37.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art_MET_DP278961.jpg.webp) Desk chair (fauteuil de bureau); 1805–1808; mahogany, gilt bronze and satin-velvet upholstery; 87.6 × 59.7 × 64.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

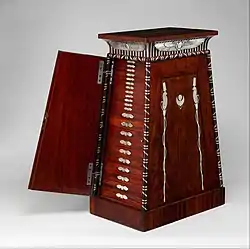

Desk chair (fauteuil de bureau); 1805–1808; mahogany, gilt bronze and satin-velvet upholstery; 87.6 × 59.7 × 64.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Revival coin cabinet; by François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter; 1809–1819; mahogany (probably Swietenia mahagoni), with applied and inlaid silver; 90.2 x 50.2 x 37.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Egyptian Revival coin cabinet; by François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter; 1809–1819; mahogany (probably Swietenia mahagoni), with applied and inlaid silver; 90.2 x 50.2 x 37.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Armchair; by Karl Friedrich Schinkel; circa 1828; gilded mountain ash, brass mounts and casters, modern upholstery; 90.2 x 61.6 x 59.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Armchair; by Karl Friedrich Schinkel; circa 1828; gilded mountain ash, brass mounts and casters, modern upholstery; 90.2 x 61.6 x 59.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Table; circa 1833-1834; hard-paste porcelain, gilded bronze, and yellow metal, iron and wood as support materials; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Table; circa 1833-1834; hard-paste porcelain, gilded bronze, and yellow metal, iron and wood as support materials; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Clocks and candelabrums

Candelabrum; circa 1800; gilt and patinated metal; overall: 49.9 x 25.7 x 12.3 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US)

Candelabrum; circa 1800; gilt and patinated metal; overall: 49.9 x 25.7 x 12.3 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US)

Pair of candelabra with Winged Victories; 1810–1815; gilt bronze; height (each): 127.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Pair of candelabra with Winged Victories; 1810–1815; gilt bronze; height (each): 127.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Mantel clock called The Reader; by Jean-Andre Reiche; circa 1810; matte and polished gilt bronze and "Vert de Mer" marble; 31 x 15 x 26 cm; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Montreal, Canada)[6]

Mantel clock called The Reader; by Jean-Andre Reiche; circa 1810; matte and polished gilt bronze and "Vert de Mer" marble; 31 x 15 x 26 cm; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Montreal, Canada)[6]

Ceramic

%252C_part_of_Breakfast_Service_(d%C3%A9jeuner)_MET_DT5175.jpg.webp) Teapot (théière Asselin), part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain; height (with handle): 20.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Teapot (théière Asselin), part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain; height (with handle): 20.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)_MET_LC-56_29_7.jpg.webp) Saucer, part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain; height: 3.2 cm; diameter: 16.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Saucer, part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain; height: 3.2 cm; diameter: 16.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art_MET_LC-56_29_3ab-001.jpg.webp) Sugar bowl with cover, part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain; height: 21 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sugar bowl with cover, part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain; height: 21 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art%252C_part_of_Breakfast_Service_(d%C3%A9jeuner)_MET_LC-56_29_4-004.jpg.webp) Milk jug (pot à lait Étrusque), part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain; height (with handle): 21.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Milk jug (pot à lait Étrusque), part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain; height (with handle): 21.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art%252C_part_of_Breakfast_Service_(d%C3%A9jeuner)_MET_DT5174.jpg.webp) Tray (plateau), part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain; 2.5 x 37.5 x 33.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Tray (plateau), part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain; 2.5 x 37.5 x 33.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art%252C_part_of_Breakfast_Service_(d%C3%A9jeuner)_MET_LC-56_29_5-002.jpg.webp) Cup (tasse Jasmin), part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain and silver gilt; height: 11.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cup (tasse Jasmin), part of a breakfast service (déjeuner); 1813; hard-paste porcelain and silver gilt; height: 11.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art One of a pair of Clodion vases; 1817; hard-paste porcelain; Louvre

One of a pair of Clodion vases; 1817; hard-paste porcelain; Louvre_MET_DT8080.jpg.webp) Fruit or flower basket (corbeille aux cygnes); 1823; hard-paste porcelain; height: 36 cm, diameter: 40.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fruit or flower basket (corbeille aux cygnes); 1823; hard-paste porcelain; height: 36 cm, diameter: 40.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fashion

_MET_DT1994.jpg.webp) Portrait of Madame Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Périgord, from circa 1804

Portrait of Madame Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Périgord, from circa 1804 1809 illustration which shows how male Empire fashion looks like, from Journal des dames et des modes

1809 illustration which shows how male Empire fashion looks like, from Journal des dames et des modes%252C_Prince_de_Talleyrand_MET_DP148275.jpg.webp) Portrait of Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Périgord, from 1817

Portrait of Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Périgord, from 1817

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Empire interiors. |

Notes

- (Honour 1977, p. 171)

- Honour 1977, p. 172

- Fredlund, Jane (2008). Stilguiden: möbler & inredning 1700–2000 (in Swedish) (2nd ed.). Stockholm: Prisma. p. 108. ISBN 9789151849874. OCLC 234047178.

- Sylvie, Chadenet (2001). French Furniture • From Louis XIII to Art Deco. Little, Brown and Company. p. 103 & 105.

- Ecaterina Oproiu, Tatiana Corvin (1975). Enciclopedia căminului (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 44 & 45.

- "MANTEL CLOCK "LA LISEUSE"". www.kollerauktionen.ch.

References

- Honour, Hugh (1977) [1968]. Neo-classicism. Style and Civilisation (reprinted with revisions ed.). London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140137606. OCLC 36284165.

.jpg.webp)