Estes Park, Colorado

Estes Park /ˈɛstɪs/ is a statutory town in Larimer County, Colorado, United States. A popular summer resort and the location of the headquarters for Rocky Mountain National Park, Estes Park lies along the Big Thompson River. Estes Park had a population of 5,858 at the 2010 census. Landmarks include The Stanley Hotel and The Baldpate Inn. The town overlooks Lake Estes and Olympus Dam.

Estes Park, Colorado | |

|---|---|

Statutory town | |

Estes Park Golf Course | |

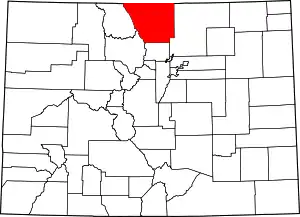

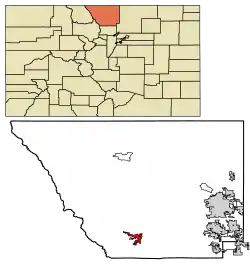

Location of Estes Park in Larimer County, Colorado. | |

| Coordinates: 40°22′38″N 105°31′32″W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Colorado |

| County[2] | Larimer |

| Founded | 1859 |

| Incorporated (town) | April 17, 1917[3] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Statutory town[2] |

| • Mayor | Wendy Koenig-Schuett |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.89 sq mi (17.83 km2) |

| • Land | 6.81 sq mi (17.64 km2) |

| • Water | 0.07 sq mi (0.19 km2) 0.85% |

| Elevation | 7,522 ft (2,293 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 5,858 |

| • Estimate (2019)[5] | 6,426 |

| • Density | 943.47/sq mi (364.29/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-6 (MDT) |

| ZIP Codes[6] | 80517 |

| Area code(s) | 970 Exchanges: 577,586 |

| FIPS code | 08-25115 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0204674 |

| Website | estes.org |

Early history

Before Europeans came to the Estes Park valley, the Arapaho Indians lived there in the summertime and called the valley "the Circle." When three elderly Arapahoes visited Estes Park in 1914, they pointed out sites they remembered from their younger days. A photograph at the Estes Park Museum identified the touring party as Shep Husted, guide; Gun Griswold, a 73-year-old judge; Sherman Sage, a 63-year-old chief of police; Tom Crispin, 38-year-old reservation resident and interpreter; Oliver W. Toll, recorder; and David Robert Hawkins, a Princeton student.[7]

In the 1850s, the Arapaho had spent summers camped around Mary's Lake, where their rock fireplaces, tipi sites, and dance rings were still visible. They also recalled building eagle traps atop Long's Peak to get the war feathers coveted by all tribes. They remembered their routes to and from the valley in detail, naming trails and landmarks. They pointed out the site of their buffalo trap, and described the use of dogs to pack meat out of the valley. Their recollections included a battle with Apaches in the 1850s, and fights with Utes who came to the area to hunt bighorn sheep, so all three of those tribes used the valley's resources.[8]

Whites probably came into the Estes Park valley before the 1850s as trappers, but did not stay long. The town is named after Missouri native Joel Estes,[9] who founded the community in 1859.[10] Estes moved his family there in 1863. One of Estes' early visitors was William Byers, a newspaper editor who wrote of his attempted ascent of Long's Peak in 1864, publicizing the area as a pristine wilderness.[11]

Griff Evans and his family came to Estes Park in 1867 to act as caretakers for the former Estes ranch. Recognizing the potential for tourism, he began building cabins to accommodate travelers. Soon it was known as the first dude ranch in Estes Park, with guides for hunting, fishing, and mountaineering.[12]

The 4th Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl, a young Anglo-Irish peer, arrived in late December 1872 under the guidance of Texas Jack Omohundro, subsequently made numerous visits, and decided to take over the valley for his own private hunting preserve. Lord Dunraven's 'land grab' didn't work, but he controlled 6,000 acres before he changed tactics and opened the area's first resort, the Estes Park Hotel, which was destroyed by fire in 1911.[13]

In 1873, Englishwoman Isabella Bird, the daughter of an Anglican minister, came to the United States. Landing at San Francisco, she came overland to Colorado, where she borrowed a horse and set out to explore the Rocky Mountains with a guide, the notorious James Nugent, aka 'Rocky Mountain Jim'. She wrote A Lady's Life in the Rocky Mountains, a memoir of their travels, including the breathtaking ascent of Long's Peak, where she was literally hauled up the steep pitches "like a bale of goods."[14]

On June 19, 1874, Rocky Mountain Jim and neighbor Griff Evans (see above) had an argument. Having had bitter history with each other, Nugent and Evans hated each other and were deep personal rivals when it came to tour guiding tourists. The argument escalated until Evans blasted Jim in the head with his rifle shotgun. Evans then traveled to Fort Collins to file an assault charge against Nugent, but he was arrested and tried for first degree murder when Jim Nugent died on September 9, 1874, of the bullet wound. Evans was put on trial, but the case was soon dismissed due to the lack of witnesses to the shooting. On August 9, 1875, the Loveland court-house acquitted Evans of any charges in the case.

William Henry Jackson photographed Estes Park in 1873.[15]

Alex and Clara (Heeney) MacGregor arrived soon after and homesteaded at the foot of Lumpy Ridge. The MacGregor Ranch has been preserved as a historic site. In 1874, MacGregor incorporated a company to build a new toll road from Lyons, Colorado, to Estes Park. The road became what is today U.S. Highway 36. Before that time, however, the "road" was only a trail fit for pack horses. The improved road brought more visitors into Estes Park; some of them became full-time residents and built new hotels to accommodate the growing number of travelers.[16]

In 1884, Enos Mills (1870-1922) left Kansas and came to Estes Park, where his relative Elkanah Lamb lived. That move proved significant for Estes Park because Mills became a naturalist and conservationist who devoted his life after 1909 to preserving nearly a thousand square miles of Colorado as Rocky Mountain National Park. He succeeded and the park was dedicated in 1915.[17]

Enos Mills' younger brother Joe Mills (1880-1935) came to Estes Park in 1889. He wrote a series of articles about his youthful experiences for Boys Life which were later published as a book. After some years as a college athletics coach, he and his wife returned to Estes Park and built a hotel called The Crags on the north side of Prospect Mountain, overlooking the village. They ran that business in the summer while he continued his coaching career in winters at University of Colorado in Boulder.[18]

Many early visitors came to Estes Park in search of better health. The Rocky Mountain West especially attracted those with pulmonary diseases, and in Estes Park some resorts catered to them, providing staff physicians for their care.[19]

Later history

In 1903, a new road was opened from Loveland through the Big Thompson River canyon to Estes Park, increasing access to the valley. In 1907, three Loveland men established the first auto stage line from Loveland to Estes Park with three five-passenger touring Stanley Steamers. The following year, Mr. Stanley built nine-passenger steam busses and opened a bus line between Lyons and Estes Park.[20]

By 1912, Estes Park had its own seasonal newspaper, the Estes Park Trail, which provided advertising for the local hotels and other businesses. It was a year-round weekly by 1921.[21] In 1949, Olympus Dam was finished, creating Lake Estes, giving the town its main source of drinking water.

Today, Estes Park's outskirts include The Stanley Hotel, built in 1909. An example of Edwardian opulence, the building had Stephen King as a guest, inspiring him to change the locale for his novel The Shining from an amusement park to the Stanley's fictional stand-in, the Overlook Hotel. Olympus Dam, on the outskirts of the town, is the dam that creates Lake Estes, a lake which is the site for boating and swimming in Estes Park. There are some hotels on the shore, including the Estes Park Resort.

Land was still being homesteaded in the area in 1914, when Katherine Garetson (1877-1963) filed on land near the base of Long's Peak. She built a cabin and started a business known as the Big Owl Tea Place. She proved up on her homestead claim in 1915, and left a memoir of her years there.[22]

In 1916 the Estes Valley Library was founded by the Estes Park Women's Club. It originally formed part of the old schoolhouse and contained only 262 printed works.[23]

Estes Park was also the site of the organization of the Credit Union National Association, an important milestone in the history of American credit unions.[24]

Trail Ridge Road, the highest continuous highway in the United States, runs from Estes Park westward through Rocky Mountain National Park, reaching Grand Lake over the continental divide.[25]

The town suffered severe damage in July 1982 from flooding caused by the failure of Lawn Lake Dam.[26] The flood's alluvial fan can still be seen on Fall River Road. The downtown area was extensively renovated after the flood, and a river walk was added between the main street, Elkhorn Avenue, and the Big Thompson River.

Geography

Estes Park sits at an elevation of 7,522 feet (2,293 m) on the front range of the Rocky Mountains at the eastern entrance of the Rocky Mountain National Park. Its location is 40°22′22″N 105°31′09″W.[27] Its north, south and east extremities border the Roosevelt National Forest. Lumpy Ridge lies immediately north of Estes Park.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 5.9 square miles (15 km2), of which 5.8 square miles (15 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) (0.85%) is water.

Climate

Estes Park has a humid continental climate (Koppen: Dfb). Summers days are typically warm, sometimes hot, while winter days are usually cold, with lows dropping into the teens and sometimes the single digits.

| Climate data for Estes Park, Colorado | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 53 (12) |

56 (13) |

67 (19) |

74 (23) |

82 (28) |

89 (32) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

89 (32) |

76 (24) |

68 (20) |

54 (12) |

92 (33) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 38 (3) |

41 (5) |

47 (8) |

55 (13) |

64 (18) |

74 (23) |

80 (27) |

78 (26) |

70 (21) |

60 (16) |

46 (8) |

39 (4) |

57 (14) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 17 (−8) |

19 (−7) |

23 (−5) |

29 (−2) |

37 (3) |

44 (7) |

51 (11) |

48 (9) |

41 (5) |

32 (0) |

24 (−4) |

17 (−8) |

32 (0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −43 (−42) |

−40 (−40) |

−30 (−34) |

−19 (−28) |

4 (−16) |

16 (−9) |

21 (−6) |

18 (−8) |

7 (−14) |

−8 (−22) |

−28 (−33) |

−35 (−37) |

−43 (−42) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.72 (44) |

1.59 (40) |

1.55 (39) |

1.83 (46) |

2.03 (52) |

1.89 (48) |

2.22 (56) |

2.64 (67) |

2.09 (53) |

1.74 (44) |

1.51 (38) |

1.86 (47) |

22.67 (574) |

| Source: [28][29] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1930 | 417 | — | |

| 1940 | 994 | 138.4% | |

| 1950 | 1,617 | 62.7% | |

| 1960 | 1,175 | −27.3% | |

| 1970 | 1,616 | 37.5% | |

| 1980 | 2,703 | 67.3% | |

| 1990 | 3,184 | 17.8% | |

| 2000 | 5,413 | 70.0% | |

| 2010 | 5,858 | 8.2% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 6,426 | [5] | 9.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[30] | |||

In August 1900, Estes Park[31] had a population of 218 in 63 households. Many (73) were born in Colorado. Eighteen were born in other countries: Canada (4), England (4), Germany (4), Finland (3), and one each from the Netherlands, Scotland, and Ireland. Eighty had been born in midwestern states, and thirty from states in the northeast.[32]

As of the census[33] of 2010, 5,858 people, 2,796 households, and 1,565 families resided in the town of Estes Park. The population density was 929.5 inhabitants per square mile (358.9/km2). There were 4,107 housing units at an average density of 570.6 per square mile (220.3/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 91.0% White, 0.3% African American, 0.5% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 2% Pacific Islander, 5.5% from other races, and 1.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 14% of the population.

There were 2,541 households, out of which 20.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.3% were married couples living together, 6.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.4% were non-families. 31.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.11 and the average family size was 2.61.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 17.6% under the age of 18, 5.8% from 18 to 24, 26.6% from 25 to 44, 29.4% from 45 to 64, and 20.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.7 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $43,262, and the median income for a family was $55,667. Males had a median income of $31,573 versus $20,767 for females. The per capita income for the town was $30,499. About 3.2% of families and 4.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.6% of those under age 18 and 0.8% of those age 65 or over.

Three million tourists visit Rocky Mountain National Park each year; most use Estes Park as their base.[34]

Historic ski areas

Estes Park was home to a number of now defunct ski areas:[35]

- Davis Hill[36]

- Hidden Valley[37]

- Leydman Hill Jump[38]

- Old Man Mountain[39]

Estes Park vicinity was also the home of other resorts and tourist attractions.[35]

Major flooding events

Flood of 1982

The town flooded in 1982 and suffered extensive damage due to the failure, "after years of disrepair and neglect", of an earthen dam several miles upstream.[26]

Flood of 2013

Both U.S. Highway 36 and U.S. Highway 34, the major routes into town, were severely damaged. Hundreds of Estes Park residents were also isolated by the destruction of sections of Fish Creek Road and all nine crossings across Fish Creek. Damaged sewer lines dumped raw sewage down the creek and into the Big Thompson River.[40]

Transportation

Public transportation

The main airport serving Estes Park is Denver International Airport, located 75 miles southeast. Service between the airport and Estes Park is provided by local carriers.[41]

The town of Estes Park operated Estes Transit, a free shuttle during the summer months.[42]

Highways

US 34 is an east-west highway that runs from Granby, Colorado to Berwyn, Illinois. In Colorado, it connects Estes Park to Loveland, Interstate 25, Greeley and Interstate 76.

US 34 is an east-west highway that runs from Granby, Colorado to Berwyn, Illinois. In Colorado, it connects Estes Park to Loveland, Interstate 25, Greeley and Interstate 76. US 36 begins at the nearby Rocky Mountain National Park, running to Uhrichsville, Ohio, passing through Kansas, Missouri, Illinois and Indiana. It connects Estes Park to Boulder, and Interstates 25 and 76, both near Denver.

US 36 begins at the nearby Rocky Mountain National Park, running to Uhrichsville, Ohio, passing through Kansas, Missouri, Illinois and Indiana. It connects Estes Park to Boulder, and Interstates 25 and 76, both near Denver. State Highway 7 begins at the junction of US 36 and N St. Vrain Avenue in Estes Park and runs to Boulder, Lafayette and Brighton. Its northwestern segment is part of the Peak-to-Peak Scenic Byway.

State Highway 7 begins at the junction of US 36 and N St. Vrain Avenue in Estes Park and runs to Boulder, Lafayette and Brighton. Its northwestern segment is part of the Peak-to-Peak Scenic Byway.

Sister city

Estes Park's official sister city is Monteverde, Costa Rica.

Notable people

- Jacob M. Appel, author, wrote The Mask of Sanity while living in Estes Park[43]

- Tommy Caldwell, rock climber

- Tom Hornbein, mountaineer & anesthesiologist. He was part of the U.S. expedition that climbed Mt. Everest in 1963. He and Willi Unsoeld were the first climbers to reach the summit via the West Ridge route, and the first to complete a traverse of a major Himalayan peak by descending by a different route than the one used to summit. In climbing circles, his climb is considered to be among the great feats in the history of mountaineering. He also designed the oxygen masks for the climb.

- Loren Shriver astronaut, commander on STS mission that launched the Hubble Telescope

- Justin E. Smith, sheriff of Larimer County since 2011; former Estes Park resident

- Freelan Oscar Stanley inventor of the Stanley Steamer and builder of the Stanley Hotel

- William Ellery Sweet, 23rd governor of Colorado, built a summer home in Estes Park in 1912, now used as a residence by his descendants

Popular culture references

- Estes Park was the setting for Nicholas Sansbury Smith's Trackers series of novels.

- The Stanley Hotel inspired Stephen King to write the novel The Shining. He checked into the hotel in 1973 for a one-night stay with his wife Tabitha.

See also

References

- "2014 U.S. Gazetteer Files: Places". United States Census Bureau. July 1, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- "Active Colorado Municipalities". State of Colorado, Department of Local Affairs. Archived from the original on 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- "Colorado Municipal Incorporations". State of Colorado, Department of Personnel & Administration, Colorado State Archives. 2004-12-01. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "ZIP Code Lookup". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original (JavaScript/HTML) on March 5, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- "Shep Husted, Arapaho Tour".

- Clement Yore, "Estes Park Region was Formerly the Playground of the Arapaho Indians," Estes Park Trail, January 27, 1922, p. 7 and February 3, 1922, pp. 7-8. An account of unidentified Indians raiding white ranches for horses is given in Abner Sprague, "Roads and Trails," Estes Park Trail, December 8, 1922, p. 3.

- "Profile for Estes Park, Colorado, CO". ePodunk. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- "Estes Park Colorado". Estes Park Colorado. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- William Byers, "Ascent of Long's Peak," Rocky Mountain News, September 23, 1864, p. 2, quoted in James H. Pickering, "This Blue Hollow": Estes Park, the Early Years, 1859-1915 (Boulder, Colo: University Press of Colorado, 1999), chapter 1.

- Betty D. Freudenburg, Facing the Frontier: The Story of the MacGregor Ranch(Estes Park, Colo.: Rocky Mountain Nature Association, 2005), p. 61.

- Freudenburg pp. 61-67.

- Isabella Bird, A Lady's Life in the Rocky Mountains (Sausalito, Calif.: Comstock, 1980), Letter 7, p. 87.

- USGS photo in Freudenburg, p. 56.

- Freudenburg, chapter 7.

- Pickering, "This Blue Hollow": Estes Park, the Early Years, 1859-1915, pp. 220-235.

- A Mountain Boyhood (New York: J.H. Sears, 1926, republished 1988 by University of Nebraska Press), introduction.

- Pickering, This Blue Hollow, 127-128.

- "First Auto Stage Line to Estes Park Established Spring of 1907," Estes Park Trail, January 5, 1923, p. 1.

- Colorado Historic Newspapers, http://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/Default/Skins/Colorado/Client.asp?skin=Colorado&AW=1364318345023&AppName=2

- Katherine Garetson, Homesteading Big Owl, 2d ed. (Allenspark, Colo.: Allenspark Wind, 2001).

- Estes Valley Library

- Creating CUNA Archived 2008-03-10 at the Wayback Machine)

- "Rocky Mountain National Park - Park Area: Trail Ridge Road". Rmnp.com. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- Ann Depperschmidt (2009-07-12). "Path of destruction:Flood of 1982 still evident in hike to Lawn Lake". Reporter-Herald. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Monthly Averages for Estes Park, CO (80517)". Weather.com. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- Weather America Ed. Alfred Garwood 1996.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Does The Estes Park Real Estate Market Need More Regulations?". Estes Park Home Search. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- U.S. census, Estes Park precinct, Larimer County, Colorado, August 1900.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Associated Press, "Rocky Mountain National Park sees more visitors" Nov 25, 2010 Denver Post

- TCSP. "''Northern Front Range Resorts''". Colorado Ski History. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- TCSP. "''Davis Hill''". Colorado Ski History. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- Colorado Ski History: Hidden Valley (Ski Estes Park)

- TCSP. "''Leydman Hill Jump''". Colorado Ski History. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- TCSP. "''Old Man Mountain''". Colorado Ski History. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- Fort Collins Coloradoan (September 17, 2013). "Estes Park vows to rebound from ravages of flood". 9news.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- "DIA Airport Shuttle Schedule and Rates | Estes Park Shuttle". Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- "Estes Transit (Free Shuttles) | Town of Estes Park". Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- Writing Today, June 2017, P. 3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Estes Park, Colorado. |

Estes Park travel guide from Wikivoyage

Estes Park travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official website