Falkes de Breauté

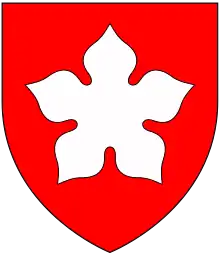

Sir Falkes de Bréauté (died 1226) (also spelled Fawkes de Bréauté or Fulk de Brent) was an Anglo-Norman soldier who earned high office by loyally serving first King John and later King Henry III in the First Barons' War. He played a key role in the Battle of Lincoln Fair in 1217. He attempted to rival Hubert de Burgh, and as a result fell from power in 1224.[2] His "heraldic device" is now popularly said to have been a griffin,[3] although his coat of arms as depicted by Matthew Paris (d.1259) in his Chronica Majora (folio 64/68 verso) was Gules, a cinquefoil argent.[4]

When he married the widow Margaret de Redvers, she was an heiress and the last of her father's Baldwin de Redvers line, and the Earl of Devon's line became extinct. The title was inherited by Isabella de Fortibus, owner of the Isle of Wight, whose extensive fortune became the property of Hugh de Courtenay, the next Earl of Devon and Baron of Okehampton. Fawkes' new wife's home in London was then called "Fawkes Hall" (Falkes' Hall), which over the years changed into "Foxhall" and finally into "Vauxhall". The Vauxhall car company derived its name from that part of London and still uses de Bréauté's griffin as its badge.[3] The house stood on approximately 31 acres in the royal manor of Kennington; it was the centre of tension between the Archbishop at Lambeth Palace and the monks of Canterbury, who tried to influence the election of English bishops.

Early life

De Bréauté was of obscure Norman parentage, and has been described as the illegitimate child of a Norman knight and a concubine, possibly a knightly family from the village of Bréauté. Most chroniclers, however, describe him as from common stock, and he was often referred to only by his first name, which was said to be derived from the scythe he had once used to murder someone,[5] as a sign of contempt.

Service under John

The first accurate records of his royal service are from 1206, when he was sent to Poitou by King John on royal service. Upon his return in February 1207 he was entrusted with the wardenship of Glamorgan and Wenlock, and around that time also knighted. He was then made constable of Carmarthen, Cardigan and the Gower Peninsula, and gained a fearsome reputation in the Welsh Marches. He was sent to destroy Strata Florida Abbey in 1212 for its opposition to the king, though the abbey was spared after the abbot paid a heavy fine of 700 Marks.[6] He served regularly in royal service, including in trips to Flanders and Poitou, and was in high favour with the king. It is often said that he was a foreign mercenary condemned by Magna Carta; this is incorrect, and he was actually one of the royalists who swore to abide by the charter's terms.[7]

Bréauté rose to power during the First Barons' War as an unquestioning subject of King John, earning the hate of baronial and monastic leaders alike. He earned the title of John's steward in 1215, a title he kept until the following year.[8] On 28 November 1215, de Bréauté captured Hanslope, Buckinghamshire, a castle of William Mauduit, and he soon after captured Bedford Castle belonging to William de Beauchamp, and in reward was allowed to keep it. In 1216 John divided his army between William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury and four "alien" captains, one of whom was de Bréauté. When Prince Louis of France invaded in the same year de Bréauté was tasked with holding Oxford against the baronial forces. On 17 July he and the Earl of Chester sacked Worcester, which had allied itself with Louis. In reward John gave de Bréauté the hand of Margaret the daughter of Warin Fitzgerald, the royal chamberlain. She was the widow of Baldwin de Revières (Redvers), former heir to the Earl of Devon, who had died in 1216, and after the death of the 5th Earl in 1217 her son became the 6th Earl. So this marriage made de Bréauté "the equal of an earl" as he was regent for the Earldom until his stepson the 6th Earl reached his majority.[9] As Margaret's dowry he gained control of the Isle of Wight, and as part of her inheritance took Stogursey, also becoming chamberlain to the Exchequer. When John died on 19 October de Bréauté served as the executor of his will, and was one of the royalists who reissued Magna Carta on 12 November 1216.

Service under Henry III

Under Henry III de Bréauté continued to fight with the same loyalty he had shown John. The Charter of liberties was a re-issue of Magna Carta and alongside it a Charter of Forests. The two were known as Magna Carta when published in November 1217. That Christmas the regents and Henry stayed at Fawkes castle in Northampton. He was holding seven High Sheriffdoms including Cambridgeshire, Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire and Bedfordshire he presented a major obstacle to Louis and the barons, although he lost Hertford and Cambridge in 1217. On 22 January of that year de Bréauté and his men had committed their worst atrocity, attacking St Albans because it had come to terms with Prince Louis, although it had done so under duress. After attacking the townspeople his men turned on the abbey, killing the abbot's cook and only leaving after blackmailing the abbot for 200 marks. His men also attacked Wardon Abbey, and although he eventually compensated St Albans it was felt he only did so to please his wife.

At the end of February he led a royalist force in an unsuccessful attempt to relieve the port of Rye. After this he captured the Isle of Ely, before playing a critical role in the campaign leading up to the Battle of Lincoln Fair. He joined the Earl of Chester to besiege Mountsorrel, and in response the rebels were forced to divide their forces, with Prince Louis and half his forces remaining at the siege of Dover while the rest marched north to relieve Mountsorrel. After achieving this the rebels marched to Lincoln to assist a rebel force besieging Lincoln Castle; while the town had fallen to the rebels, the castle garrison had remained loyal to King Henry. By the time they got there the royalist force had already arrived under the command of William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, and he forced a battle in the streets of the town itself. Before the battle began de Bréauté had led his force into the castle itself, and his crossbowmen shot down at the rebel force from the walls. Sallying out himself, with such force that he was captured before being rescued by his men, he fought on until the rebels fled, with even the Angevin leaders acknowledging his role in a critical victory against superior forces.[10][11]

In reward for his role in the victory the royal court celebrated Christmas at his expense at Northampton, but this proved the climax of his career. After the battle he was one of the many fighters who was alienated by Hubert de Burgh, Justiciar of England, over them keeping the castles they had captured for their own profit. Due to his role in the campaign and the victory at Lincoln itself he was unassailable for many years; he deflected judgements made against him in 1218 and 1219 and kept hold of his High Sheriffdoms, including that of Rutland. Between 1218 and 1219 he also served as a Justice of the Peace for Essex, Hertfordshire and East Anglia, and when William de Redvers, 5th Earl of Devon died he was given the castle of Plympton.

He had made many enemies due to his actions during the war; numbered among them were William Marshal, who pawned four manors to him during the war and had difficulty getting them back, and the Earl of Salisbury, who grew to dislike him after de Bréauté supported Nicola de la Haie for constable of Lincoln Castle against Salisbury's personal preference. Due to his status as a commoner his position was more tenuous than that of his enemies, as he had no lands to base himself on, and relied increasingly on the favour of noblemen such as the Earl of Chester and Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester, who supported him due to their disenchantment with the rule of Hubert de Burgh. In 1222 he cooperated with de Burgh to suppress a revolt by the citizens of London, capturing three of the ringleaders and executing them without trial.

Rebellion

De Burgh's growing ascendancy drew de Bréauté and his allies even closer together, but tensions boiled over in November 1223,[12] when de Burgh and the king were forced to flee to Northampton while de Bréauté, the Count of Aumale and the earls of Chester and Gloucester attempted to seize the Tower of London. A new civil war was averted by the intervention of Simon Langton, Archbishop of York, but after a parley in London on 4 December failed tensions rose again. Threatened with excommunication the "schismatics" returned to the king's court, agreeing on 30 December to give their castles and shrievalties to the king. De Bréauté immediately lost Hertford Castle and the shrievalties of Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire, and lost the rest of his shrievalties by 18 January 1224.[13]

The failure of de Bréauté and his allies gave the advantage to de Burgh, who in February 1224 ordered de Bréauté to give up Plympton and Bedford castles, rejecting his claim that Plympton Castle was part of his wife's inheritance. De Bréauté refused to give the castles up, and in response the royal court sent justices to his land with a fake charge of Breach of the Peace. They found him guilty of 16 counts of Wrongful Disseisin, and on 16 June William de Bréauté, Falkes' brother, seized Henry of Braybrooke, one of the justices of Dunstable, who ruled against de Bréautés in 16 suits under the new royal writs. Braybrooke had made himself a personal enemy of both de Bréautés. This was foolish in the extreme, as the King and his court were barely 20 miles away discussing the defence of Poitou. On 20 June the king and his forces besieged Bedford Castle, with Simon Langton excommunicating both the brothers and the garrison as a whole. The siege lasted eight weeks, with over 200 killed by missiles sent by castle defenders. After a fourth assault broke the walls William and 80 knights were captured, refused pardon and hanged.[14]

Exile

Having lost Bedford and his brother, Falkes submitted to Henry III on 19 August, pleading for forgiveness in exchange for the loss of all his possessions.[15] At this his wife left him and pleaded for divorce, claiming she had been forced into the marriage eight years before; she was unsuccessful, but did manage to recover some of her lands. On 25 August Falkes officially gave up his lands, and chose exile to France rather than judgement from the barons.[5] Arriving in Normandy he was imprisoned by Louis VIII in Compiègne as revenge for his defeat of the French forces during the war, but was released in 1225 either through the intervention of the pope or through his Crusader's Badge, assumed in 1221. After release he spent several months in Rome, and published a fourteen-page defence of his actions, the querimonia, which laid the blame at the feet of Langton and de Burgh, and begged the pope to support him as a man excommunicated without cause and as a crusader. Departing for England, de Bréauté was captured in Burgundy by an English knight he had once imprisoned, but papal intervention yet again saw his release. After this he lived in Troyes, but was expelled from France in 1226 for refusing to pay homage to the king, and again stayed in Rome, dying slightly before 18 July, allegedly from a poisoned fish.

Vauxhall

The part of London beside the Thames near the present Vauxhall Bridge known as Vauxhall seems originally to have been part of the extensive Manor of South Lambeth, which was held in the 13th century by the de Redvers family. The name Vauxhall (Fauxhall) is derived from Falkes de Bréauté, the second husband of Margaret, widow of Baldwin de Redvers.[3][16]

In 1857 the Vauxhall Ironworks were founded in the Vauxhall area of south London as a steam pump and marine engine manufacturer. The company built the first Vauhall car in 1903. In 1905, seeking to build a dedicated factory for car manufacture on cheaper land with room for expansion, the firm relocated to a new site in Luton, Bedfordshire. By pure coincidence de Bréauté also held the manor of Luton between 1216 and 1226, with the Vauxhall company relocating from his London seat to his country seat. The griffin of the de Bréauté coat of arms was in use in both Vauxhall and Luton between the 13th and 20th centuries. The firm was renamed Vauxhall Motors in 1907 and still uses the griffin as its badge.[3]

References

- Suzanne Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora, University of California Press, 1987, p.449

- R. Pauli, ed. J.M. Lappenberg Geschichte von England (Friedrich Perthes, Hamburg 1853), III, pp. 538-44 (Google), (in German), with references there cited.

- Article from Vauxhall V Magazine reproduced on Bedford OB Get-Together web site Archived 19 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Suzanne Lewis: The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora. University of California Press, 1987, p.449

- Carpenter, David (2003). The Struggle for Mastery. Oxford University Press US. p. 306. ISBN 0-19-522000-5.

- "Strata Florida Abbey, Wales".

- D.J. Power, 'Bréauté, Sir Falkes de', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004).

- S.D. Church, The Household Knights of King John (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 9. ISBN 0-521-55319-9.

- D.A. Carpenter, The Struggle for Mastery: Britain, 1066-1284 (Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 306 (Google).

- The Battle of Lincoln (1217), according to Roger of Wendover Archived 24 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- The Battle of Lincoln, 1217, from the History of William the Marshal; original at P. Meyer (ed), L'Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal, Comte de Striguil et de Pembroke, Société de l'Histoire de France, 2 vols (Librairie Renouard, Paris 1894), II, pp. 217 ff. (Internet Archive). (in Norman French).

- D.A. Carpenter, The Reign of Henry III (Continuum International Publishing Group, 1996), p. 46. ISBN 1-85285-137-6.

- M. Ray, 'The Companions of Falkes de Bréauté and the siege of Bedford Castle', Fine of the Month, July 2007 Henry III Fine Roll Project.

- W. Stubbs, The Constitutional History of England, 4th Edition, 3 vols (Clarendon Press, Oxford 1896), II, pp. 35-36 (Internet Archive), with references there cited.

- A copy of his deed of surrender was entered in the Close Rolls, and is printed by T. Stapleton in Preface, De antiquis legibus liber: Cronica maiorum et vicecomitum Londoniarum (etc) Camden Society XXXIV (London 1846), at pp. lviii-lix (Google).

- 'Vauxhall and South Lambeth: Introduction and Vauxhall Manor', in F.H.W. Sheppard (ed.), Survey of London, Volume 26: Lambeth: Southern Area (London, 1956), pp. 57-59 (British History Online).

- M.G.I. Ray, 'Alien knights in a hostile land: the experience of curial knights in thirteenth-century England and the assimilation of their families', Historical Research Vol. 79 no 206 (November 2006), pp. 451–76. (at pp. 455, 459, 463, 466–67, 469–71, 474.)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bréauté, Falkes de". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bréauté, Falkes de". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ralph Hareng |

High Sheriff of Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire 1217–1224 |

Succeeded by Walter of Pattishall |

| Preceded by Henry of Braybrooke |

High Sheriff of Northamptonshire 1215–1223 |

Succeeded by Unknown |

| Preceded by Henry of Braybrooke |

High Sheriff of Rutland 1215–1224 |

Succeeded by Unknown |

| Preceded by Unknown |

High Sheriff of Cambridgeshire 1215–1224 |

Succeeded by Unknown |

| Preceded by Unknown |

High Sheriff of Oxfordshire 1215–1224 |

Succeeded by Unknown |