Poitou

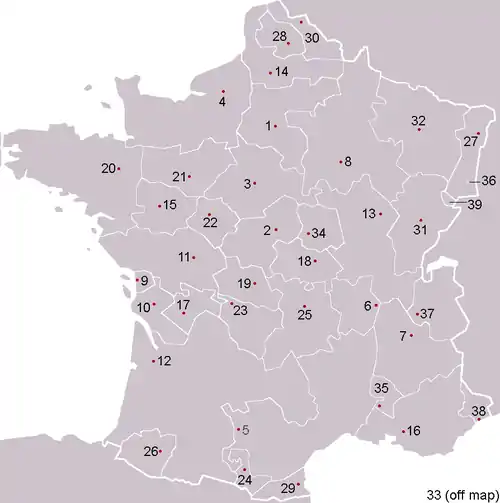

Poitou (UK: /ˈpwʌtuː/, US: /pwɑːˈtuː/,[2][3][4] French: [pwatu]; Poitevin: Poetou) was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers.

Poitou

| |

|---|---|

Flag .svg.png.webp) Coat of arms | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Country | France |

| Area | |

| • Total | 19,709 km2 (7,610 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,375,356 |

| Time zone | CET |

| Count | 638–677, Guérin de Trèves 1403–1461, Charles VII of France |

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical capital city), Châtellerault (France's kings' establishment in Poitou), Niort, La Roche-sur-Yon, Thouars, and Parthenay.

History

A marshland called the Poitevin Marsh (French Marais Poitevin) is located along the Gulf of Poitou, on the west coast of France, just north of La Rochelle and west of Niort.

At the conclusion of the Battle of Taillebourg in the Saintonge War, which was decisively won by the French, King Henry III of England recognized his loss of continental Plantagenet territory to France. This was ratified by the Treaty of Paris of 1259, by which King Louis annexed Normandy, Maine, Anjou, and Poitou).

During the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, Poitou was a hotbed of Huguenot (French Calvinist Protestant) activity among the nobility and bourgeoisie. The Protestants were discriminated against and brutally attacked during the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598). Under the Edict of Nantes, such discrimination was temporarily suspended but this measure was repealed by the French Crown.

Some of the French colonists, later known as Acadians, who settled beginning in 1604 in eastern North America came from southern Poitou. They established settlements in what is now Nova Scotia, and later in New Brunswick—both of which were taken over in the later 18th century by the English, (after their 1763 victory in the Seven Years' War).

After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, the French Roman Catholic Church conducted a strong Counter-Reformation effort. In 1793, this effort had contributed to the three-year-long open revolt against the French Revolutionary Government in the Bas-Poitou (Département of Vendée). Similarly, during Napoleon's Hundred Days in 1815, the Vendée stayed loyal to the Restoration Monarchy of King Louis XVIII. Napoleon dispatched 10,000 troops under General Lamarque to pacify the region.

As noted by historian Andre Lampert,

"The persistent Huguenots of 17th Century Poitou and the fiercely Catholic rebellious Royalists of what came be the Vendée of the late 18th Century had ideologies very different, indeed diametrically opposed to each other. The common thread connecting both phenomena is a continuing assertion of a local identity and opposition to the central government in Paris, whatever its composition and identity. (...) In the region where Louis XIII and Louis XIV had encountered stiff resistance, the House of Bourbon gained loyal and militant supporters exactly when it had been overthrown and when a Bourbon loyalty came to imply a local loyalty in opposition to the new central government, that of Robespierre."[5]

In fiction

- Large parts of the "Angelique" series of historical novels are set in 17th century Poitou.

See also

- Count of Poitiers for a list of the Comtes de Poitou.

- Poitevin (language), the French regional language spoken in Poitou (Saintongeais is for Saintonge).

- Big Ghoul, folklore dragon.

References

- Lance Day, Ian McNeil, ed. (1996). Biographical Dictionary of the History of Technology. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-19399-0.

- "Poitou". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Poitou" (US) and "Poitou". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Poitou". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- Andre Lampert, "Centralism and Localism in European History" (cited as an example of "A Persistant [sic] Localism" in the Introduction)

External links

Media related to Poitou at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Poitou at Wikimedia Commons- Le Poitou, ancienne province de France : Portrait physique et humain du Poitou aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles at the Wayback Machine (archived 12 August 2002)