Framlingham Castle

Framlingham Castle is a castle in the market town of Framlingham in Suffolk in England. An early motte and bailey or ringwork Norman castle was built on the Framlingham site by 1148, but this was destroyed (slighted) by Henry II of England in the aftermath of the revolt of 1173–4. Its replacement, constructed by Roger Bigod, the Earl of Norfolk, was unusual for the time in having no central keep, but instead using a curtain wall with thirteen mural towers to defend the centre of the castle. Despite this, the castle was successfully taken by King John in 1216 after a short siege. By the end of the 13th century, Framlingham had become a luxurious home, surrounded by extensive parkland used for hunting.

| Framlingham Castle | |

|---|---|

| Framlingham, Suffolk, England | |

The Inner Court and Lower Court from the northwest | |

Framlingham Castle | |

| Coordinates | 52°13′27″N 1°20′49″E |

| Grid reference | grid reference TM 286 636 |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Largely intact |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Flint, septaria and sandstone |

| Events | Revolt of 1173–4, First Barons' War, Second World War |

During the 15th and 16th centuries Framlingham was at the heart of the estates of the powerful Mowbray and Howard families. Two artificial meres were built around the castle, which was expanded in fashionable brick. With a large, wealthy household to maintain, the castle purchased supplies from across England and brought in luxury goods from international markets. Extensive pleasure gardens were built within the castle and older parts redesigned to allow visitors to enjoy the resulting views. By the end of the 16th century, however, the castle fell into disrepair and after the final Howard owner, Theophilus, entered into financial difficulties the castle and the surrounding estates were sold off.

Framlingham Castle was given to Pembroke College (University of Cambridge) as a philanthropic gesture in 1636, after which the internal buildings were taken down to make way for the construction of a workhouse within the site. The castle was used in this way until 1839 when the facility was closed; the castle was then used as a drill hall and as a county court. In 1913, Pembroke College placed Framlingham into the guardianship of the Commissioner of Works. During the Second World War, Framlingham Castle was used by the British military as part of the regional defences against a potential German invasion. Today, Framlingham Castle is managed by English Heritage and run as a tourist attraction. It is protected under UK law as a grade I listed building and a scheduled monument.

History

11th–12th centuries

The population of Framlingham in Suffolk rose sharply after the Norman invasion of England as the village turned into a small town of at least 600 inhabitants, surrounded by valuable lands in one of the most prosperous parts of the country.[1] The region was owned by the powerful Hugh d'Avranches, the Earl of Chester, who granted it in turn to Roger Bigod, the Sheriff of Suffolk. A ringwork or motte and bailey castle was first built in either the 11th or early 12th century in the northern half of the Inner Court of the current castle.[2]

Although the first documentary reference to a castle at Framlingham occurs in 1148, the actual date of its construction is uncertain and three possible options have been suggested by academics. The first possibility is that the castle was built by Roger Bigod in either the late 11th century or around 1100, similar to the founding of Bigod's caput at nearby Eye.[3] A second possibility is that Roger's son, Hugh Bigod, built it during the years of the Anarchy in the 1140s on the site of an existing manor house; the castle would then be similar to the Bigod fortification at Bungay.[4] A third possibility is that there were in fact two castles: the first being built in the late 11th century and then demolished by Hugh Bigod in the 1160s in order to make way for a newer, larger castle.[5] Historian Magnus Alexander hypothesizes the castle might have been built on top of a set of pre-existing Anglo-Saxon, high prestige buildings, a practice common elsewhere in East Anglia, possibly echoing the arrangement at Castle Acre; this would be most likely if the castle was built in the 11th century.[6][nb 1]

By the late 12th century the Bigod family had come to dominate Suffolk, holding the title of the Earl of Norfolk and owning Framlingham and three other major castles at Bungay, Walton and Thetford.[8] The first set of stone buildings, including the first hall, were built within the castle during the 1160s.[9] Tensions persisted throughout the period, however, between the Crown and the Bigods. Hugh Bigod was one of a group of dissenting barons during the Anarchy in the reign of King Stephen, and after coming to power Henry II attempted to re-establish royal influence across the region.[10] As part of this effort, Henry confiscated the four Bigod castles from Hugh in 1157, but returned both Framlingham and Bungay in 1165, on payment of a large fine of £666.[11][nb 2]

Hugh then joined the revolt by Henry's sons in 1173. The attempt to overthrow Henry was unsuccessful, and in punishment the king ordered several Bigod castles, including Framlingham, to be destroyed (slighted).[13] The king's engineer, Alnoth, destroyed the fortifications and filled in the moat at Framlingham between 1174–6 at a total cost of £16 11s 12d, although he probably shored up, rather than destroyed, the internal stone buildings.[14][nb 3]

Hugh's son, Roger Bigod, was out of favour with Henry, who initially denied him the family earldom and estates such as Framlingham.[16] Roger finally regained royal favour when Richard I succeeded to the throne in 1189.[16] Roger then set about building a new castle on the Framlingham site – the work was conducted relatively quickly and the castle was certainly complete by 1213.[17] The new castle comprised the Inner Court, defended with 13 mural towers; an adjacent Lower Court with smaller stone walls and towers, and a larger Bailey with timber defences.[18] By this time, a castle-guard system was in place at Framlingham, in which lands were granted to local lords in return for their providing knights or soldiers to guard the castle.[19]

13th century

The First Barons' War began in 1215 between King John and a faction of rebel barons opposed to his rule. Roger Bigod became one of the key opponents to John, having argued over John's requirements for military levies.[20] Royal troops plundered the surrounding lands and John's army arrived on 12 March 1216, followed by John the next day.[21] With John's permission, messages were sent on the 14th from the castle to Roger, who, influenced by the fate of Rochester Castle the previous year, agreed that the garrison of 26 knights, 20 sergeants, 7 crossbowmen and a priest could surrender without a fight.[22] John's forces moved on into Essex, and Roger appears to have later regained his castle, and his grandson, another Roger, inherited Framlingham in 1225.[23][nb 4]

A large park, called the Great Park, was created around the castle; this park is first noted in 1270, although it may have been constructed somewhat earlier.[24] The Great Park enclosed 243 hectares (600 acres) stretching 3 km (1.9 mi) to the north of the castle, and was characterised by possessing bank-and-ditch boundaries, common elsewhere in England but very unusual in Suffolk.[25][nb 5] The park had a lodge built in it, which later had a recreational garden built around it.[26] Like other parks of the period, the Great Park was not just used for hunting but was exploited for its wider resources: there are records of charcoal-burning being conducted in the park in 1385, for example.[27] Four other smaller parks were also located near the castle, extending the potential for hunting across a long east-west belt of emparked land.[28]

In 1270 Roger Bigod, the 5th Earl, inherited the castle and undertook extensive renovations there whilst living in considerable luxury and style.[29] Although still extremely wealthy, the Bigods were now having to borrow increasing sums from first the Jewish community at Bungay and then, after the expulsion of the Jews, Italian merchants; by the end of the century, Roger was heavily in debt to Edward I as well.[30] As a result, Roger led the baronial opposition to Edward's request for additional taxes and support for his French wars.[30] Edward responded by seizing Roger's lands and only releasing them on the condition that Roger granted them to the Crown after his death.[30] Roger agreed and Framlingham Castle passed to the Crown on his death in 1306.[30]

By the end of the 13th century a large prison had been built in the castle; this was probably constructed in the north-west corner of the Lower Court, overlooked by the Prison Tower.[31] The prisoners kept there in the medieval period included local poachers and, in the 15th century, religious dissidents, including Lollard supporters.[31]

14th century

Edward II gave the castle to his half-brother, Thomas of Brotherton, the Earl of Norfolk.[30] Records show that Framlingham was only partially furnished around this time, although it is unclear if this was because it was in limited use, or because fittings and furnishings were moved from castle to castle with the owner as he traveled, or if the castle was simply being refurnished.[32] The castle complex continued to thrive, however, on Thomas' death in 1338, the castle passed first to his widow, Mary de Brewes, and then in 1362, into the Ufford family.[30] William de Ufford, 2nd Earl of Suffolk held the castle during the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, with much of the revolt occurring close to Framlingham.[33] From the Uffords, the castle passed first to Margaret of Brotherton, the self-styled "Countess-Marshall", and then to Thomas de Mowbray, the Duke of Norfolk.[34] The Mowbrays seem to have used Framlingham Castle as their main seat of power for most of the 15th century.[33]

With as many as 83 people living in the castle at any one time, the castle played a major role in the surrounding economy during the period.[35] Large amounts of food and drink were purchased to support the household – over twelve months in 1385-6, for example, over £1,000 was spent, including the purchase of 28,567 imperial gallons (129,870 L) of ale and 70,321 loaves of bread.[36][nb 6] By the 14th century the castle was purchasing goods from across western Europe, with wine being imported from France, venison from parks as far away as Northamptonshire and spices from the Far East through London-based merchants.[38] The castle purchased some goods, such as salt, through the annual Stourbridge Fair at nearby Cambridge, then one of the biggest economic events in Europe.[38] Some of this expenditure was supported by the demesne manor attached to the castle, which comprised 168 hectares (420 acres) of land and 5,000 days of serf labour under feudal law.[39] A vineyard was created at the castle in the late 12th century, and a bakery and a horse mill were built in the castle by the 14th century.[40] Surrounding manors also fed in resources to the castle; in twelve months between 1275–6, £434 was received by the castle from the wider region.[38][nb 7]

Two large lakes, called meres, were formed alongside the castle by damming a local stream.[26] The southern mere, still visible today, had its origins in a smaller, natural lake; once dammed, it covered 9.4 hectares (23 acres) and had an island with a dovecote built on it.[41][nb 8] The meres were used for fishing as well as for boating, and would have had extensive aesthetic appeal.[43] It is uncertain exactly when the meres were first built.[44] One theory suggests that the meres were built in the early 13th century, although there is no documentary record of them at least until the 1380s.[45] Another theory is that they were formed in the first half of the 14th century, at around the same time as the Lower Court was constructed.[44] A third possibility is that it was the Howard family who introduced the meres in the late 15th century as part of their modernisation of the castle.[46]

15th–16th centuries

In 1476 the castle passed to John Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, who probably began the sequence of improvements to the castle during the Tudor period.[47] Under the Howards the castle was extensively modernised; fashionable brick was used to improve parts of the castle; ornamental chimneys were added; the battlements were reduced in size to exaggerate the apparent height of the walls, and the Howard coat of arms was added to the gatehouse.[46] The Great Chamber was probably built across the Inner Court at this time, linking the Great Hall with the chapel and chambers on the east side of the castle, and by 1524 there were at least 29 different rooms in the castle.[48] The drawbridge outside the gatehouse was replaced with the current permanent bridge between 1524–47; by this time a half-moon defensive structure had been built in stone to defend it.[49] A pleasure garden had been built in the Lower Court by the 16th century, with several ornamental ponds and terraced walkways – the garden would probably have also had fruit trees, herb gardens and fountains.[50] Another pleasure garden was built in the Bailey, and a second bridge built across the moat to allow access to it directly from the Inner Court.[36] The Prison Tower was redesigned to become a viewing gallery for the new formal gardens below.[31]

The Wars of the Roses during the 15th century saw prolonged fighting between the Yorkists and Lancastrians for the control of the English throne. John Howard, a Yorkist supporter, was killed at Bosworth Field in 1485 and in the aftermath his son Thomas, the 2nd Duke, was attainted, forfeiting his and his heirs' rights to his properties and titles, and placed in the Tower of London.[47] The Lancastrian victor at Bosworth, Henry VII, granted Framlingham Castle to John de Vere, but Thomas finally regained the favour of Henry VIII after fighting at the victory of Flodden in 1513.[47] Framlingham was returned to Thomas and the Duke spent his retirement there; he decorated his table at the castle with gold and silver plate that he had seized from the Scots at Flodden.[47] The castle was expensively decorated in a lavish style during this period, including tapestries, velvet and silver chapel fittings and luxury bedlinen.[51] A hundred suits of armour were stored in the castle and over thirty horses kept in the stables.[52]

The 3rd Duke of Norfolk, also called Thomas, made far less use of the castle, using first Stoke-by-Nayland and then Kenninghall as his principal residence.[47] Thomas was attainted in 1547 for his part in supporting the claim of Mary to the throne; Henry VIII died the day before Thomas was due to be executed at the Tower, and his successor, Mary's half-brother Edward VI, reprieved Thomas but kept him in the Tower, giving Framlingham to Mary.[53] When Mary seized power in 1553 she collected her forces at Framlingham Castle before successfully marching on London.[54] Thomas was released from the Tower by Mary as a reward for his loyalty, but retired to Kenninghall rather than Framlingham.[55] The castle was leased out but when the 4th Duke, another Thomas, was executed for treason by Elizabeth I in 1572 the castle passed back to the Crown.[56]

Repairs to the castle appear to have been minimal from the 1540s onwards, and after Mary left Framlingham the castle went into a fast decline.[57] A survey in 1589 noted that the stonework, timber and brickwork all needed urgent maintenance, at a potential cost of £100.[54] The Great Park was disparked and turned into fields in 1580.[58] As religious laws against Catholics increased, the castle became used as a prison from 1580 onwards; by 1600 the castle prison contained 40 prisoners, Roman Catholic priests and recusants.[59]

17th–21st centuries

In 1613 James I returned the castle to Thomas Howard, the Earl of Suffolk, but the castle was now derelict and he chose to live at Audley End House instead.[60] Thomas's son, Theophilus Howard, fell heavily into debt and sold the castle, the estate and the former Great Park to Sir Robert Hitcham in 1635 for £14,000; as with several other established parks, such as Eye, Kelsale and Hundon, the Great Park was broken up turned into separate estates.[61][nb 9] Hitcham died the following year, leaving the castle and the manor to Pembroke College in Cambridge, with the proviso that the college destroy the internal castle buildings and construct a workhouse on the site instead, operating under the terms of the recently passed Poor Law.[63]

After the collapse of the power of the Howards, the county of Suffolk was controlled by an oligarchy of Protestant gentry by the 17th century and did not play a prominent part in the English Civil War that occurred between 1642–6.[64] Framlingham Castle escaped the slighting that occurred to many other English castles around this time.[65] Hitcham's bequest had meanwhile become entangled in the law courts and work did not begin on the workhouse until the late 1650s, by which time the internal buildings of castle were being broken up for the value of their stone; the chapel had been destroyed in this way by 1657.[66]

The workhouse at Framlingham, the Red House, was finally built in the Inner Court and the poor would work there so they were eligible for relief;[67] it proved unsatisfactory and, following the mismanagement of the workhouse funds, the Red House was closed and used as a public house instead.[68] The maintenance of the meres ceased around this time and much of the area returned to meadow.[69] In 1699 another attempt was made to open a poorhouse on the site, resulting in the destruction of the Great Chamber around 1700.[70] This poorhouse failed too, and in 1729 a third attempt was made – the Great Hall was pulled down and the current poorhouse built on its site instead.[68] Opposition to the Poor Law grew, and in 1834 the law was changed to reform the system; the poorhouse on the castle site was closed by 1839, the inhabitants being moved to the workhouse at Wickham Market.[68]

The castle continued to fulfil several other local functions. During the outbreak of plague in 1666, the castle was used as an isolation ward for infected patients, and during the Napoleonic Wars the castle was used to hold the equipment and stores of the local Framlingham Volunteer regiment.[71] Following the closure of the poorhouse, the castle was then used as a drill hall and as a county court, as well as containing the local parish jail and stocks.[72]

In 1913 the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act was passed by Parliament and Pembroke College took the opportunity to place Framlingham into the guardianship of the Commissioner of Works.[73] The undulating Inner Court was levelled up to its present form as part of the Commissioner's maintenance works.[74] During the Second World War, Framlingham was an important defensive location for British forces; at least one concrete pill box was built near to the castle as part of the plans to counter any German invasion, and Nissen huts were erected and a lorry park created in the Bailey.[75]

Today, Framlingham Castle is a scheduled monument and a grade I listed building, managed by English Heritage and run as a tourist attraction, incorporating the Lanman Museum of local history.[76] The castle mere is owned by Framlingham College and run by the Suffolk Wildlife Trust.[77]

Architecture

Design

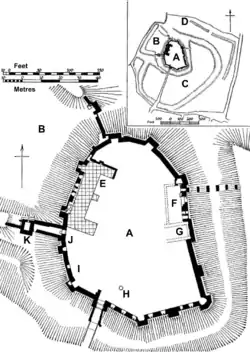

Framlingham Castle is located on a bluff overlooking the River Ore, and today is made up of three distinct parts, the Inner Court, the Bailey and the Lower Court, surrounded by the remaining mere and farmland.[78]

The Bailey lies to the south of the walled Inner Court and was originally topped by a wooden palisade and earthworks, of which only the latter survive.[79] The Bailey would have entered from an eastern gate and contained a range of buildings, probably including a Sergeant's Chamber, a Knights' Chamber, the Great Stable, barns and a granary.[80] Modern visitors to the castle enter the complex through the Bailey from the south, which also contains the modern car park for the castle.[81]

The Inner Court, or the Castle, lies beyond the Bailey across the 15th-century bridge that replaced the earlier drawbridge on the site.[82] The gate tower that forms the entrance is a relatively simple design from the 12th century: the fashion for much grander gatehouse designs began shortly afterwards.[83] The 2nd Duke of Norfolk, Thomas Howard, however, had it remodelled in the 16th century, adding his coat of arms and additional ornamentation to the walls.[84] The Inner Court is formed around a stone curtain wall of local flint and septaria stone, 10.5 m (34 ft) high and 2.3 m (7.5 ft) thick, protected by thirteen square mural towers with open backs, each around 14.3 m (47 ft) high, with corners made of sandstone.[85] A wall-walk runs around the top of the towers and wall.[86]

Originally various buildings were built around the curtain wall. Moving clockwise from the entrance to the Inner Court, the shape of the 12th-century castle chapel can still be made out on the curtain wall.[87] Convention at the time required a chapel to point along a north-east/south-east axis; in order to achieve this, the chapel had to extend out considerably into the bailey, similar to the design at White Castle.[88] The chapel is adjacent to the site of the first stone hall in the castle, built around 1160; in the 16th and 17th centuries the chapel tower was probably also used as a cannon emplacement.[89]

On the far side of the Inner Court is the poorhouse, built on the site of the 12th-century Great Hall.[90] The poorhouse forms three wings: the 17th century Red House to the south, the 18th-century middle wing, and the northern end which incorporates part of the original Great Hall; all of the building was subject to 19th-century renovation work.[91] Five carved, medieval stone heads are set into the poorhouse, taken from the older medieval castle buildings.[92] Next to the poorhouse is the Postern Gate, which leads to the Prison Tower.[93] The Prison Tower, also called the Western Tower, is a significant defensive work, redesigned in the 16th century to feature much larger windows.[31] In the middle of the Inner Court is the castle well, 30 m (98 ft) deep.[94]

A number of carved brick chimneys dating from the Tudor period can be seen around the Inner Court, each with a unique design; all but three of these were purely ornamental, however, and historian R. Allen Brown describes them as a "regrettable" addition to the castle from an architectural perspective.[95] Two of the functional Tudor chimneys make use of original mid-12th century flues; these two chimneys are circular in design and are the earliest such surviving structures in England.[96]

One of the castle meres can still be seen to the west of the castle, although in the 16th century there were two lakes, much larger than today, complete with a wharf.[97] This dramatic use of water to reflect the image of the castle is similar to that used at several other castles of the period, including Bredwardine and Ravensworth Castle.[97] Water castles such as Framlingham made greater use of water than was necessary for defence and enhanced the appearance of the castle.[98] The view from the Great Hall in the Inner Court would originally have included the gardens of the Lower Court, and these would have then been framed by the mere and the Great Park beyond.[99] The area around the castle today remains a designed and managed landscape; although the Great Park is now covered by fields, the view still gives a sense of how the castle and landscape was meant to appear to its late medieval owners.[100]

Interpretation

The late 12th-century defences at Framlingham Castle have invoked much debate by scholars. One interpretation, put forward for example by historian R. Allen Brown, is that they were relatively advanced for their time and represented a change in contemporary thinking about military defence.[101] Framlingham has no keep, for example – this had been a very popular feature in previous Anglo-Norman castles, but this castle breaks with the tradition, relying on the curtain wall and mural towers instead.[102] The pattern of ground-level arrowslits at Framlingham were similarly innovative for their time, enabling interlocking and flanking fire against attackers.[103] The design of Framlingham's defences is similar in many ways to Henry II's innovative work at Dover and Orford.[104]

The defensive architecture of the castle also contains various weaknesses. The Inner Court is overlooked by the Bailey, for example; the north of the Inner Court is largely exposed, while the positioning of arrow-slits in the curtain wall ignores much of the castle.[105] The open-backed mural towers, whilst cheaper to build than closed towers, could not have been easily defended once the wall had been penetrated, and because they projected only a little way from the wall, they provided very little options for enfilading fire against attackers close to the walls.[106] These weaknesses have been used by historians such as Robert Liddiard to argue that the architecture of castles such as Framlingham were influenced by cultural and political requirements as well as purely military intent.[107]

Focusing on the cultural and political use of the architecture at Framlingham, historian D. Plowman has put forward a revisionist interpretation of the castle's architecture in the late medieval period. Plowman suggests that the castle was intended to be entered from the north end of the Lower Court, passing through the ornamental gardens, with travellers then entering through the gate by the Prison Tower – in this interpretation, more of a barbican than a tower – and then up into the Inner Court.[108] This would have provided high status visitors with dramatic views of the castle, reinforcing the political prestige of the owners.[108] Historian Magnus Alexander disputes the practicality of this arrangement, although agrees that the route would have been more practical for hunting parties proceeding to the local parklands.[105]

In popular culture

Pop singer Ed Sheeran, who grew up in Framlingham, references the castle in his 2017 single, Castle on the Hill.

See also

- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of castles in England

- Church of St Michael the Archangel, Framlingham

- Castle on the Hill, a song by Ed Sheeran that references the castle

- The place where the BBC shot a sketch for CBBC programme, Horrible Histories

Notes

- Nicola Stacey and John Rigard prefer the late 11th century date for the founding of the castle; Magnus Alexander prefers the 1140s; J. Coad has proposed the two-castle option. The 11th century date carries the disadvantage of having no documentary evidence, and being slightly unusual for East Anglia, where the regional lords built relatively fewer castles during this period. The 1140s option closes the time gap with the first documentary reference in 1148 and fits well with Hugh Bigod becoming an Earl in 1140, but raises the question of what the Bigods had done with the site during the first forty years of their ownership. The two-castle model also lacks firm supporting evidence.[7]

- It is impossible to accurately compare 12th century and modern prices or incomes. For comparison, £666 is approximately the annual income of the wealthiest baron in England around 1200.[12]

- It is impossible to accurately compare 12th century and modern prices or incomes. For comparison, £16 represents the approximate cost of maintaining an average sized castle for a year during the period.[15]

- The date on which Roger Bigod recovered Framlingham is unclear from the historical sources.

- Bank and ditch boundaries are designed to permit game animals to enter the park by jumping over the bank, but prevent them from leaving by means of an interior ditch.

- It is impossible to accurately compare 14th century and modern prices or incomes. For comparison, £1,000 represents the typical average annual income for an early 15th-century baron.[37]

- It is impossible to accurately compare 13th century and modern prices or incomes. For comparison, £434 represents around two-thirds the average income for a major baron of the period.[12]

- By placing the dovecote on an island, the surrounding mere would have protected the doves from vermin.[42]

- It is difficult to accurately compare 17th century and modern prices or incomes. £14,000 could equate to between £1,790,000 to £22,700,000, depending on the measure used. For comparison, Henry Somerset, one of the richest men in England at the time, had an annual income of around £20,000.[62]

References

- Alexander, pp.12–13; Dyer, p.63.

- Alexander, p.17, citing Coad, pp155-8.

- Stacey, p.23; Ridgard, p.2; Alexander, p.17.

- Alexander, pp.17–8.

- Alexander, p.18; Coad, p.160.

- Alexander, p.18.

- Stacey, p.23; Ridgard, p.2; Coad, p.160; Alexander, p.17.

- Pounds, p.55; Brown (1962), p.191.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.21.

- Pounds, p.55.

- Brown (1962), p.191; Carpenter, p.224; Stacey, p.24.

- Pounds, p.147.

- Alexander, p.17.

- Alexander, p.17; Ridgard, p.3.

- Pounds, p.123.

- Brown (2002), cited Alexander, p.20.

- Alexander, p.20.

- Stacey, p.17; Raby and Reynolds, p.6.

- King, pp.16–7.

- Liddiard (2005), p.94; Stacey, p.25.

- Liddiard (2005), p.94.

- Liddiard (2005), pp.83, 94.

- Liddiard (2005), p.94; Stacey, p.26.

- Taylor, p.40; Alexander, p.26.

- Hoppitt, pp.152, 161; Taylor, p.40.

- Taylor, p.40.

- Liddiard (2005), p.104.

- Alexander, p.31.

- Stacey, pp.26–7.

- Ridgard, p.4.

- Stacey, p.11.

- Alexander, pp.20–1; Ridgard, p.4.

- Ridgard, p.5.

- Ridgard, p.5; Stacey, p.28.

- Smedley, p.53, cited Alexander, p.21.

- Alexander, p.21.

- Pounds, p.148.

- Alexander, p.22.

- Ridgard, p.19.

- Ridgard, pp.13, 21.

- Taylor, p.40; Liddiard (2005), p.114; Stacey, p.16.

- Alexander, p.30.

- Liddiard (2005), p.106.

- Alexander, p.29.

- Alexander, pp.29–30.

- Johnson, p.45.

- Ridgard, p.6.

- Alexander, p.21; Stacey, p.21; Ridgard, p.130.

- Alexander, p.21; Raby and Reynolds, p.18.

- Taylor, p.40l; Stacey, p.17.

- Stacey, pp.7–8, 19.

- Stacey, p.21.

- Ridgard, pp.6–7; Stacey, p.33.

- Ridgard, p.7.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.13; Stacey, p.34.

- Raby and Reynolds, pp.13–4.

- Ridgard, pp.6–7.

- Hoppitt, pp.161–2; Alexander, p.44.

- Alexander, p.44; Ridgard, p.7; Stacey, p.36.

- Alexander, p.45; Raby and Reynolds, p.14.

- Hoppitt, pp.161–2; Alexander, p.44; Stacey, pp.36–7.

- Financial comparison based on the RPI index, using Measuring Worth Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present, MeasuringWorth, accessed 24 June 2011; Pugin, p.23.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.14; Stacey, p.37.

- Hughes, p.144.

- Jenkins, p.713.

- Alexander, pp.45; Stacey, p.38.

- Cole & Morrison 2016, p.2–4.

- Stacey, p.38.

- Alexander, p.44.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.14.

- Stacey, pp.38–9.

- Alexander, p.49; Stacey, p.40.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.14; Alexander, p.50.

- Alexander, p.50.

- Alexander, p.50; Stacey, p.40.

- Stacey, p.17.

- Stacey, p.40.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.16.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.30.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.31.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.15.

- Raby and Reynolds, pp.17–18.

- Pounds, p.149.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.18 Stacey, p.6.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.19; Stacey, p.5.

- Stacey, p.10.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.22.

- Pounds, p.240.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.21; Stacey, p.14.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.24.

- Raby and Reynolds, pp.25–6; Stacey, pp.7, 10.

- Stacey, pp.7–8.

- Raby and Reynolds, p.27.

- Stacey, p.7.

- Ridgard, p.3; Stacey, pp.5, 15.

- Stacey, p.14.

- Creighton, p.79.

- Plowman, p.44.

- Liddiard (2005), p.115.

- Taylor, p.40; Liddiard (2005), p.114.

- Brown (1962), p.61.

- Liddiard (2005), p.47.

- King, p.84; Liddiard (2005), p.93.

- Brown (1962), p.66; Stacey, p.5.

- Alexander, p.24.

- Toy, p.171; King, p.92.

- Liddiard (2005), p.6.

- Plowman, pp.44–6, cited Alexander, p.24.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Magnus. (2007) Framlingham Castle, Suffolk: The Landscape Context, Desktop Assessment. London: English Heritage Research Department. ISSN 1749-8775.

- Brown, M. (2002) Framlingham Castle, Framlingham, Suffolk: Archaeological Investigation Series 24/2002. London: English Heritage.

- Brown, R. Allen. (1962) English Castles. London: Batsford. OCLC 1392314.

- Carpenter, David. (2004) Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-014824-4.

- Coad, J. G. (1972) "Recent Excavations Within Framlingham Castle," Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History, 32, pp. 152–163.

- Cole, Emily and Morrison, Kathryn. (June 2016) The Red House (formerly Framlingham Workhouse), Framlingham Castle, Suffolk. Research Report Series No. 23/2016. London: English Heritage.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton. (2005) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8.

- Dyer, Christopher. (2009) Making a Living in the Middle Ages: The People of Britain, 850 – 1520. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10191-1.

- Johnson, Matthew. (2002) Behind the Castle Gate: from Medieval to Renaissance. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-25887-6.

- Hoppitt, Rosemary. (2007) "Hunting Suffolk's Parks: Towards a Reliable Chronology of Imparkment," in Liddiard (ed) (2007).

- Hughes, Ann. (1998) The Causes of the English Civil War. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21708-2.

- Jenkins, Simon. (2003) England's Thousand Best Houses. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9596-1.

- Liddiard, Robert. (2005) Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2.

- Liddiard, Robert. (ed) (2007) The Medieval Park: New Perspectives. Bollington, UK: Windgather Press. ISBN 978-1-905119-16-5.

- Plowman, D. (2005) "Framlingham Castle, a Political Statement?" Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History 41, pp43–49.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1994) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a social and political history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Pugin, Augustus. (1895) Examples of Gothic Architecture Selected From Various Ancient Edifices in England. Edinburgh: J. Grant. OCLC 31592053.

- Raby, F. J. E. and P. K. Baillie Reynolds (1974) Framlingham Castle, Suffolk. London: Her Majesty"s Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11670-097-1.

- Ridgard, John. (1985) Medieval Framlingham: Select Documents 1270–1524. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-432-9.

- Smedley, W. (2005) "A Newly Discovered Fragment of a Daily Account Book for Framlingham Castle, Suffolk," Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History, 41, pp. 51–5.

- Stacey, Nicola. (2009) Framlingham Castle. London: English Heritage. ISBN 978-1-84802-021-4.

- Taylor, C. (1998) Parks and Gardens of Britain: A Landscape History from the Air. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-85331-207-6.

- Toy, Sidney. (1985) Castles: Their Construction and History. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-24898-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Framlingham Castle. |