French cruiser Guichen (1897)

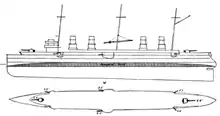

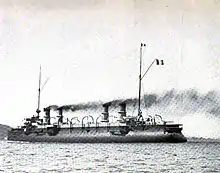

Guichen was a large protected cruiser built in the 1890s for the French Navy, the only member of her class. She was intended to serve as a long-range commerce raider, designed according to the theories of the Jeune École, which favored a strategy of attacking Britain's extensive merchant shipping network instead of engaging in an expensive naval arms race with the Royal Navy. As such, Guichen was built with a relatively light armament of just eight medium-caliber guns, but was given a long cruising range and the appearance of a large passenger liner, which would help her to evade detection while raiding merchant shipping.

Guichen | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | D'Entrecasteaux |

| Succeeded by: | Châteaurenault |

| History | |

| Name: | Guichen |

| Builder: | Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire |

| Laid down: | October 1895 |

| Launched: | 26 October 1897 |

| Completed: | November 1899 |

| Stricken: | 1921 |

| Fate: | Broken up |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement: | 8,151 long tons (8,282 t) |

| Length: | 133 m (436 ft 4 in) long between perpendiculars |

| Beam: | 16.96 m (55 ft 8 in) |

| Draft: | 7.49 m (24 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | |

| Speed: | 23.5 knots (43.5 km/h; 27.0 mph) |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

The predicted Anglo-French war that spurred Guichen's design never came, and so her early career passed uneventfully. She initially served with the Mediterranean Squadron during her lengthy sea trials, followed by a stint in the Northern Squadron. She was sent to the Far East in response to the Boxer Uprising in Qing China by early 1901, returning to France the following year. Another deployment to East Asian waters came in 1905 and ended in 1907 with her return to France. She had been reduced to reserve by 1911 and saw little further activity in the following three years.

At the start of World War I in July 1914, the ship was mobilized into the 2nd Light Squadron and tasked with patrolling the western end of the English Channel. Guichen was transferred to the Mediterranean Sea in May 1915, serving initially with the main French fleet that blockaded the Austro-Hungarian Navy in the Adriatic Sea. Later in the year, she was reassigned to the Syrian Division that patrolled the coast of Ottoman Syria, where she helped to evacuate some 4,000 Armenian civilians fleeing the Armenian Genocide. By 1917, she had been reduced to a fast transport operating between Italy and Greece. After the war, she took part in the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War in the Black Sea, but after her crew mutinied in 1919, she was recalled to France, where she was eventually struck from the naval register in 1921 and broken up.

Design

.jpg.webp)

In the mid-1880s, elements in the French naval command argued over future warship construction; the Jeune École advocated building long-range and fast protected cruisers for use as commerce raiders on foreign stations while a traditionalist faction preferred larger armored cruisers and small fleet scouts, both of which were to operate as part of the main fleet in home waters. The latter course required a direct challenge to the larger British Royal Navy, and the proponents of the Jeune École hoped to avoid the significant expense of an arms race by attacking Britain indirectly, by way of attacks on her merchant shipping. By the end of the decade and into the early 1890s, the traditionalists were ascendant, leading to the construction of several armored cruisers of the Amiral Charner class, though the supporters of the Jeune École secured approval for one large cruiser built according to their ideas, which became D'Entrecasteaux.[1]

These debates took place in the context of shifting geopolitical alliances and rivalries. The early 1890s was marked by serious strategic confusion in France; despite the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1891, which should have produced friction between the two countries and their imperial rival Britain, the French Navy was still oriented against the German-led Triple Alliance. This outlook was cemented in the naval program of 1894, but even the Navy's strategic planning remained muddled. The program authorized the large protected cruisers Guichen and Châteaurenault, both of which were intended as long-distance commerce raiders. These vessels were ideally suited to attack the extensive merchant shipping network of Britain, not the continental powers of Germany or Austria-Hungary.[1]

The designs for Guichen and Châteaurenault were based on the United States Navy's Columbia-class cruisers, using the same hull lines as the American vessels. Both ships were intended to resemble passenger liners, which would help them evade discovery while conducting commerce raiding operations. The French cruisers suffered from several defects, however, including insufficient speed to catch the fast transports that would be used to carry critical materiel in wartime and their vast expense militated against their use to attack low-value shipping. Additionally, their weak armament precluded their use against enemy cruisers.[1]

Characteristics

Guichen was 133 m (436 ft 4 in) long between perpendiculars, with a beam of 16.96 m (55 ft 8 in) and a draft of 7.49 m (24 ft 7 in). She displaced 8,151 long tons (8,282 t). Her hull featured a straight stem and a pronounced tumblehome shape, as was typical for French warships of the period. She had a spar deck that extended for most of the length of the vessel. Guichen's superstructure consisted of a main conning tower forward with a small bridge structure atop it and a smaller secondary conning tower aft. She was fitted with a pair of light pole masts for signaling purposes. Her crew numbered 604 officers and enlisted men,[2] which provided her a cruising radius of 7,500 nautical miles (13,900 km; 8,600 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[3]

The ship's propulsion system consisted of three vertical triple-expansion steam engines driving three screw propellers; she was the first French protected cruiser to adopt a three-shaft arrangement.[4] Steam was provided by thirty-six mixed oil- and coal-burning, Lagrafel d'Allest water-tube boilers. These were divided into two widely-spaced groups and both groups were ducted into a pair of funnels. Her machinery was rated to produce 25,000 indicated horsepower (19,000 kW) for a top speed of 23.5 knots (43.5 km/h; 27.0 mph). Coal storage amounted to 1,960 long tons (1,990 t).[2]

Despite her large size, Guichen carried a relatively light armament, since she was intended to engage unarmed merchant vessels, not other cruisers. Her main battery consisted of two 164 mm (6.5 in) M1893 45-caliber (cal.) quick-firing (QF) gun in single pivot mounts, fore and aft on the centerline, which fired a variety of shells, including solid cast iron projectiles, and explosive armor-piercing (AP) and semi-armor-piercing (SAP) shells. The muzzle velocity ranged from 770 to 880 m/s (2,500 to 2,900 ft/s).[2][5] These guns were supported by six 138 mm (5.4 in) M1893 45-cal. QF guns carried in sponsons, three guns per broadside.[2] They were also supplied with cast iron, AP, and SAP projectiles, firing with a muzzle velocity of 730 to 770 m/s (2,400 to 2,500 ft/s).[6] For close-range defense against torpedo boats, she was armed with a battery of ten 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and five 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder guns. The ship was also armed with a pair of 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes in her hull above the waterline. The torpedoes were the M1892 variant, which carried a 75 kg (165 lb) warhead and had a range of 800 m (2,600 ft) at a speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph).[2][7]

Armor protection consisted of Harvey steel. Guichen had a curved armor deck that was 55 mm (2.2 in) thick on the flat portion, which was about 0.79 m (2 ft 7 in) above the waterline. Toward the sides of the hull, it sloped downward to provide a measure of vertical protection, terminating at the side of the hull about 1.37 m (4 ft 6 in) below the waterline. The sloped portion increased in thickness to 100 mm (3.9 in), though toward the bow and stern, it was reduced to 40 mm (1.6 in). An anti-splinter deck was above the flat portion of the main deck with a cofferdam connecting it to the main deck. The forward conning tower was protected by 160 mm (6.3 in) on the sides; an armored supporting tube protected by 150 mm (5.9 in) of armor connected it to the interior of the ship. The ship's main guns were each fitted with gun shields that were 55 mm thick.[2]

Service history

Guichen was built at the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire shipyard Nantes; her keel was laid down there in October 1895. The ship was launched on 26 October 1897,[8] and was completed in 1899.[2] Troubles during her sea trials necessitated alterations to the ship, which delayed her joining the fleet. After tests in June 1899 where she failed to meet her design speed, the decision was made to replace her screws, along with other corrections. She completed full-power trials in November, where she made a top speed of 23.54 knots (43.60 km/h; 27.09 mph). Upon entering service that year, Guichen was assigned to the Mediterranean Squadron, France's primary battle fleet. At that time, the unit consisted of six pre-dreadnought battleships, three armored cruisers, seven other protected cruisers, and several smaller vessels. Further evaluations were carried out through early 1900, including a test on 10 February to determine the speed developed using only the outboard propellers. In March, Guichen departed the Mediterranean for the Northern Squadron.[10][11]

Guichen had been deployed to East Asia by January 1901 as part of the response to the Boxer Rebellion in Qing China; at that time, eight other cruisers were assigned to the station.[12] Fighting continued in Zhili province into February.[13] With the fighting in China having been suppressed by 1902, Guichen returned to France in company with the armored cruiser Amiral Charner.[14] She returned to service with the Northern Squadron in 1903, which was kept in commission for six months of the year.[15] She remained in the unit in 1904,[16] but later that year, she was decommissioned so her crew could be used to commission the new armored cruiser Amiral Aube.[17]

The ship returned to service for another tour in East Asia in 1905; during this period, her crew observed the Russian Second Pacific Squadron pass through Cam Ranh Bay in French Indochina in May on its way to the Battle of Tsushima of the Russo-Japanese War.[18] Guichen served as the flagship of the Naval Division of the Far East and Western Pacific until 15 August, when D'Entrecasteaux arrived to relieve her as flagship.[19] Guichen remained on station the following year,[20] but was recalled to France the following year.[21] By 1911, Guichen had been assigned to the Reserve Division of the Northern Squadron, along with the armored cruisers Dupetit-Thouars, Gueydon, Montcalm, Jeanne d'Arc, and Kléber. The unit was based in Brest.[22]

World War I

After the start of World War I in August 1914, Guichen was assigned to the 2nd Light Squadron, which at that time consisted of the armored cruisers Marseillaise, Amiral Aube, Jeanne d'Arc, Gloire,Gueydon, and Dupetit-Thouars. The unit was based in Brest, and was strengthened by the addition of several other cruisers over the following days, including the armored cruisers Kléber and Desaix, the protected cruisers Châteaurenault, D'Estrées, Friant, and Lavoisier, and several auxiliary cruisers. The ships then conducted a series of patrols in the English Channel in conjunction with a force of four British cruisers.[23]

The French began withdrawing cruisers from the Channel over the following year, particularly after the British erected the Dover Barrage, a barrier of naval mines and nets patrolled by destroyers. Guichen was among the vessels transferred to the Mediterranean in May 1915. She initially joined the main fleet, based at Malta; toward the end of the month, Italy entered the war on the side of France and the Triple Entente. The Italian fleet took over responsibility for blockading the Austro-Hungarian Navy in the Aegean Sea and the French fleet was then charged with patrolling the area between Malta and Bizerte in French Tunisia. Guichen and the armored cruiser Amiral Charner were sent to join the 1st Light Division to patrol the area between Sardinia and Capo Colonna; the unit at that time consisted of the armored cruisers Waldeck-Rousseau, Ernest Renan, and Edgar Quinet. In late July, the ships were transferred to Algiers in French Algeria.[24]

She was then transferred to the 3rd Squadron in the eastern Mediterranean and took part in a blockade of the Syrian coast, then part of the Ottoman Empire. During these patrols, she cruised with Desaix and the seaplane carrier Foudre on the northernmost section of the blockade in the vicinity of Latakia. The ships had little success, as most Ottoman shipping in the region consisted of small sailing vessels. The squadron's base at Port Said on the Suez Canal was deemed to be too far for Guichen, Desaix, and Foudre, so the French occupied the small island of Arwad to secure a closer anchorage. On 12 and 13 September, Guichen participated in the evacuation of some 4,000 Armenians from the city of Antioch, along with Amiral Charner, Desaix, D'Estrées Foudre, and the British seaplane carrier HMS Anne. Guichen under Commander Jean-Joseph Brisson was the first vessel to observe distress signals that had been sent by the Armenians, who had been pursued by Ottoman forces during the Armenian Genocide and besieged on Musa Dagh mountain. The French and British ships transported the evacuees to Port Said.[25][26][27]

In late 1915, the 3rd Squadron was reorganized and new ships replaced Guichen.[28] In April 1916, Guichen and Desaix were sent to Dakar in French Senegal to replace the 3rd Light Division. Guichen remained on the station only briefly, as a reorganization of the fleet's cruisers saw her replaced by the armored cruisers Dupleix and Kléber by July.[29] Beginning in 1917, she was used as a fast transport on the route between Taranto, Italy, and the Gulf of Corinth in Greece.[30]

Postwar

Following the war, she joined the French fleet that entered the Black Sea to intervene in the Russian Civil War in 1919.[30] In June, Guichen had withdrawn to the Gulf of Patras in western Greece, where her crew mutinied; Charles Tillon, who later led the Communist Party of France, played a significant role in the mutiny. Unrest also broke out among numerous French vessels, including in home ports, the North Sea, and elsewhere, owing to war weariness, a desire to return home, dissatisfaction with inequality aboard the ships, and anger with the fleet's anti-communist operations. The French authorities resorted to sending a battalion of Senegalese Tirailleurs to board Guichen and restore order.[31][32] After her return to France, she was struck from the naval register in 1921 and broken up.[33]

Notes

- Ropp, p. 284.

- Gardiner, p. 312.

- Garbett, p. 563.

- Gardiner, pp. 308–312.

- Friedman, p. 221.

- Friedman, p. 224.

- Friedman, p. 345.

- Weyl, p. 21.

- Brassey 1899, p. 71.

- Leyland, p. 25.

- Jordan & Caresse 2017, p. 218.

- Clayton, p. 38.

- Brassey 1902, p. 49.

- Brassey 1903, p. 60.

- Brassey 1904, p. 88.

- Garbett, p. 562.

- Thiess, p. 275.

- Jordan & Caresse 2019, p. 57.

- Brassey 1906, p. 43.

- Brassey 1907, p. 45.

- Brassey 1911, p. 56.

- Meirat, p. 22.

- Jordan & Caresse 2019, pp. 225, 233.

- Jordan & Caresse 2019, p. 235.

- Peterson, pp. 42–43.

- Schulz-Behrend, pp. 114 & 116.

- Jordan & Caresse 2019, p. 236.

- Jordan & Caresse 2019, p. 242.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 194.

- Bell & Elleman, pp. 118–119.

- Clayton, p. 72.

- Gardiner & Gray, pp. 193–194.

References

- Bell, Christopher M. & Elleman, Bruce A. (2003). Naval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century. Portland: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-5460-4.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1899). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 70–80. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1902). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 47–55. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1903). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 57–68. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1904). "Chapter IV: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 86–107. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1906). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 38–52. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1907). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 39–49. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1911). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 55–62. OCLC 496786828.

- Clayton, Anthony (2016). Three Republics One Navy: A Naval History of France 1870-1999. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-911096-74-0.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Garbett, H., ed. (May 1904). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVIII (315): 560–566. OCLC 1077860366.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2019). French Armoured Cruisers 1887–1932. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4118-9.

- Leyland, John (1900). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 24–62. OCLC 496786828.

- Meirat, Jean (1975). "Details and Operational History of the Third-Class Cruiser Lavoisier". F. P. D. S. Newsletter. Akron: F. P. D. S. III (3): 20–23. OCLC 41554533.

- Notes on Naval Progress. General Information Series, No. XVIII. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1899.

- Peterson, Merrill D. (2004). "Starving Armenians": America and the Armenian Genocide, 1915–1930 and After. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 9780813922676.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- Schulz-Behrend, George (1951). "Sources and Background of Werfel's Novel Die vierzig Tage des Musa Dagh". The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory. 26 (2): 111–123. doi:10.1080/19306962.1951.11786525.

- Thiess, Frank (1937). The Voyage of Forgotten Men. New York: Bobbs-Merrill. OCLC 1871472.

- Weyl, E. (1898). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 19–55. OCLC 496786828.