French cruiser Sfax

Sfax was a protected cruiser built for the French Navy in the 1880s. She was the first vessel of the type to be built for the French Navy, which was a development from earlier unprotected cruisers like Milan. Unlike the earlier vessels, Sfax carried an armor deck that covered her propulsion machinery and ammunition magazines. Intended to be used as a commerce raider in the event of war with Great Britain, Sfax was rigged as a barque to supplement her engines on long voyages abroad. She was armed with a main battery of six 164 mm (6.5 in) guns and a variety of lighter weapons.

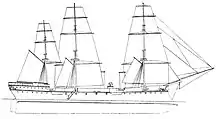

Sfax early in her career as originally configured | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Preceded by: | None |

| Succeeded by: | Tage |

| History | |

| Name: | Sfax |

| Builder: | Arsenal de Brest |

| Laid down: | March 1882 |

| Launched: | May 1884 |

| Completed: | June 1887 |

| Stricken: | 1906 |

| Fate: | Broken up |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 4,561 long tons (4,634 t) |

| Length: | 91.57 m (300 ft 5 in) lwl |

| Beam: | 15.04 m (49 ft 4 in) |

| Draft: | 7.67 m (25 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | |

| Speed: | 16.7 knots (30.9 km/h; 19.2 mph) |

| Range: | 5,500 nmi (10,200 km; 6,300 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 486 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Sfax had a relatively uneventful career. She spent most of her career alternating between the Mediterranean, Northern, and Reserve Squadrons. During this period, she was primarily occupied with conducting training exercises; while in the Reserve Squadron, she was kept in commission for only part of the year. She briefly served on the North American station in 1899, but by 1901, had been reduced to reserve. She was struck from the naval register in 1906 and subsequently broken up.

Design

In 1878, the French Navy embarked on a program of cruiser construction authorized by the Conseil des Travaux (Council of Works) for a strategy aimed at attacking British merchant shipping in the event of war. The program called for ships of around 3,000 long tons (3,048 t) with a speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph). The first three vessels of the program—Naïade, Aréthuse, and Dubourdieu—were traditional unprotected cruisers with wooden hulls, while the fourth vessel, Milan, was a transitional steel-hulled design. The Navy ordered a fifth ship similar to the wooden ships, to be named Capitaine Lucas, but by this time, the British Royal Navy had begun building their own protected cruisers. The French naval engineer Louis-Émile Bertin protested the beginning of construction of the new ship and she was cancelled before work started. Capitaine Lucas was replaced with an entirely new design, which became Sfax. The ship proved to be a successful design and she provided the basis for subsequent vessels, including Tage.[1]

Characteristics

Sfax was 91.57 m (300 ft 5 in) long at the waterline, with a beam of 15.04 m (49 ft 4 in) and a draft of 7.67 m (25 ft 2 in). She displaced 4,561 long tons (4,634 t). Her hull featured a pronounced ram bow and short fore and sterncastles. The hull was constructed with steel frames and wrought iron plating, and below the waterline it was sheathed in a layer of timber and copper plate to protect it from biofouling on extended cruises. As was typical for French warships of the period, she had a pronounced tumblehome shape and an overhanging stern. Her superstructure was minimal, consisting primarily of a small conning tower forward. Her crew consisted of 486 officers and enlisted men.[2][3]

The ship was propelled by a pair of horizontal compound steam engines, each driving a screw propeller. Steam was provided by twelve coal-burning fire-tube boilers that were ducted into two funnels located amidships. The power plant was rated to produce 6,500 indicated horsepower (4,800 kW) for a top speed of 16.7 knots (30.9 km/h; 19.2 mph). On speed trials conducted in May 1887, she reached a speed of 15.9 knots (29.4 km/h; 18.3 mph) from 4,333 ihp (3,231 kW) using natural draft and 16.84 knots (31.19 km/h; 19.38 mph) from 6,034 ihp (4,500 kW) using forced draft. Coal storage amounted to 590 long tons (600 t) normally and up to 980 long tons (1,000 t) at full load. To supplement the steam engines on long voyages, she was originally fitted with a barque sailing rig with three masts. The sail area totaled 1,990 square meters (21,400 sq ft).[2][4] Using only her steam engines, Sfax had a cruising range of 5,500 nautical miles (10,200 km; 6,300 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[5]

The ship was armed with a main battery of six 164 mm (6.5 in) 30-caliber guns carried in individual pivot mounts. Four of the guns were mounted in sponsons on the upper deck, two on each broadside, while the other two were placed in embrasures in the forecastle. These weapons were supported by a secondary battery of ten 138 mm (5.4 in) 30-caliber guns that were carried in a main deck battery amidships. For close-range defense against torpedo boats, she carried two 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and ten 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder Hotchkiss revolver cannon, all in individual mounts. She also carried five 350 mm (14 in) torpedo tubes in her hull above the waterline.[2]

The ship was protected by an armor deck that consisted of four layers of mild steel that was 61 mm (2.4 in) thick in total. The deck was placed low in the ship, about 0.61 to 0.91 m (2 to 3 ft) below the waterline. Between the armor and main deck, a cofferdam coupled with watertight compartmentalization was employed to contain flooding from damage. This section was divided by seven longitudinal and sixteen transverse bulkheads, some of which were filled with water-absorbing cellulose. Some of the compartments were used to store coal, which provided a measure of protection against enemy fire. Her conning tower had 25 mm (1 in) sides.[2][6]

Later in her career, Sfax was modernized. Her sails and mainmast were removed, and her armament was revised. New quick-firing versions of her 164 mm and 138 mm guns replaced the old weapons, and her light battery was revised to six 47 mm guns, six 37 mm guns, and four of the 37 mm Hotchkiss revolvers. Three of her torpedo tubes were removed as well.[2]

Service history

Sfax was laid down at the Arsenal de Brest in Brest, France in March 1882.[2] She was launched on 29 May 1884,[7] conducted her sea trials off Brest in May 1887,[4] and was completed in June.[2] Immediately upon entering service, Sfax participated in the fleet maneuvers with the Mediterranean Fleet that began on 11 June.[8] By 1890, Sfax had been transferred to the Northern Squadron, which was based in the English Channel. She took part in that year's naval maneuvers, along with the ironclads Marengo, Océan, and Suffren, the torpedo cruiser Epervier, and several other vessels. The exercises began on 2 July and involved the ships attacking several coastal defense ships and armored gunboats in a simulated amphibious assault of an "eastern" (i.e., German) squadron. The exercise concluded on the 5th, with the Northern Squadron having failed to neutralize the defending forces and effect a landing.[9]

Joint maneuvers were held in 1891 with the combined Mediterranean Fleet and Northern Squadron. The ships of the Mediterranean Fleet arrived in Brest on 2 July and began the maneuvers four days later; the exercises ended on 25 July.[10] The following year, Sfax was transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet, where she served as part of the reconnaissance force for the main French battle fleet, along with the cruisers Tage, Amiral Cécille, and Lalande. The ship participated in that year's fleet maneuvers, which began on 23 June and concluded on 11 July.[11] By 1893, Sfax had been reduced to the Reserve Squadron, where she spent six months of the year on active service with full crews for maneuvers; the rest of the year was spent laid up with a reduced crew. At that time, the unit also included several older ironclads and the cruisers Tage, Davout, Forbin, and Condor.[12] Sfax took part in the fleet maneuvers in 1894, still part of the Reserve Squadron; from 9 to 16 July, the ships involved took on supplies in Toulon for the maneuvers that began later on the 16th. A series of exercises included shooting practice, a blockade simulation, and scouting operations in the western Mediterranean. The maneuvers concluded on 3 August.[13]

In late January 1895, Sfax and the ironclad Amiral Duperré took part in an experimental bombardment of a simulated coastal fortification on Levant Island. The test lasted six hours and was carried out over the course of three days, so that the effect of shelling could be studied throughout the experiment. It involved over a thousand shots between the two ships, firing calibers ranging from 10 to 34 cm (3.9 to 13.4 in). Neither ship was able to significantly damage the fortifications, though several of the guns were damaged and shell fragments would have inflicted casualties among gun crews. The French determined that an excessive amount of ammunition was required to neutralize the guns, and had the fortification been returning fire, both ships likely would have been seriously damaged.[14][15] Sfax was still serving in the unit in 1895, along with the cruisers Forbin and Milan.[16] That year she took part in the fleet maneuvers, which began on 1 July and concluded on the 27th. She was assigned to "Fleet A", which along with "Fleet B" represented the French fleet, and was tasked with defeating the hostile "Fleet C", which represented the Italian fleet.[17]

She remained in the Reserve Squadron in 1896,[18] and participated in the annual maneuvers as part of the Reserve Squadron's cruiser screen, along with the cruisers Lalande, Amiral Cécille, Milan, and Léger. The maneuvers for that year took place from 6 to 30 July and the Reserve Squadron served as the simulated enemy.[19] In mid-1897, Sfax was reactivated to participate in the second phase of the exercises of the Northern Squadron. These lasted from 18 to 21 July 1897, and the scenario saw the Sfax and Tage simulate a hostile fleet steaming from the Mediterranean Sea to attack France's Atlantic coast. In the course of the exercises, the Northern Squadron successfully intercepted the cruisers and "defeated" them.[20] Sfax was modernized in 1898 at Brest; in addition to repairs to her machinery, she had her original military masts replaced with pole masts. In 1899, Sfax was assigned to the North American station, along with the unprotected cruiser Dubourdieu.[22] After Alfred Dreyfus was pardoned that year, Sfax carried him back from Devil's Island in French Guiana to Port Haliguen.[23] By January 1901, Sfax had been reduced to the 2nd category of reserve.[24] She was struck from the naval register in 1906,[2] and was subsequently broken up for scrap.[7]

Notes

- Ropp, p. 109.

- Gardiner, p. 308.

- Ropp, p. 108.

- Brassey 1888b, p. 343.

- Garbett, p. 563.

- Brassey 1886, p. 239.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 193.

- Brassey 1888a, p. 228.

- Brassey 1890, pp. 37–39.

- Brassey 1891, pp. 33–37.

- Thursfield 1892, pp. 61–67.

- Brassey 1893, p. 70.

- Barry, pp. 208–212.

- Browne, pp. 366–367.

- Lansdale & Everhart, pp. 101–103.

- Brassey 1895, p. 50.

- Gleig, pp. 195–196.

- Brassey 1896, p. 62.

- Thursfield 1897, pp. 164–167.

- Thursfield 1898, pp. 140–143.

- Brassey 1899, p. 74.

- Conner, p. 89.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 219.

References

- Barry, E. B. (1895). "The Naval Manoeuvres of 1894". The United Service: A Monthly Review of Military and Naval Affairs. Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co. XII: 177–213. OCLC 228667393.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1886). "Sfax". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 239. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1888). "Chapter XV". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 204–258. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1888). "Sfax". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 343. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1890). "Chapter II: Foreign Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1891). "Foreign Maneouvres: I—France". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 33–40. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1893). "Chapter IV: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 66–73. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1895). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 49–59. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1896). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 61–71. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1899). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 70–80. OCLC 496786828.

- Browne, Orde (1897). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Attack of Coast Batteries by French Ships". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 366–367. OCLC 496786828.

- Conner, Tom (2014). The Dreyfus Affair and the Rise of the French Public Intellectual. Jefferson: MacFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-1588-2.

- Garbett, H., ed. (May 1904). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVIII (315): 560–566. OCLC 1077860366.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Gleig, Charles (1896). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter XII: French Naval Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 195–207. OCLC 496786828.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Lansdale, Philip V. & Everhart, Lay H. (July 1896). "Notes on Ordnance and Armor". Notes on the Year's Naval Progress. Washington, D.C.: United States Office of Naval Intelligence. XV: 95–126. OCLC 727366607.

- "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLII (247): 1091–1094. September 1898. OCLC 1077860366.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1892). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Foreign Naval Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 61–88. OCLC 496786828.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1897). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Naval Maneouvres in 1896". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 140–188. OCLC 496786828.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1898). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "II: French Naval Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 138–143. OCLC 496786828.