George Robey

Sir George Edward Wade, CBE (20 September 1869 – 29 November 1954),[1] known professionally as George Robey, was an English comedian, singer and actor in musical theatre, who became known as one of the greatest music hall performers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As a comedian, he mixed everyday situations and observations with comic absurdity. Apart from his music hall acts, he was a popular Christmas pantomime performer in the English provinces, where he excelled in the dame roles. He scored notable successes in musical revues during and after the First World War, particularly with the song "If You Were the Only Girl (In the World)", which he performed with Violet Loraine in the revue The Bing Boys Are Here (1916). One of his best-known original characters in his six-decade long career was the Prime Minister of Mirth.

Born in London, Robey came from a middle-class family. After schooling in England and Germany, and a series of office jobs, he made his debut on the London stage, at the age of 21, as the straight man to a comic hypnotist. Robey soon developed his own act and appeared at the Oxford Music Hall in 1890, where he earned favourable notices singing "The Simple Pimple" and "He'll Get It Where He's Gone to Now". In 1892, he appeared in his first pantomime, Whittington Up-to-date in Brighton, which brought him to a wider audience. More provincial engagements followed in Manchester, Birmingham and Liverpool, and he became a mainstay of the popular Christmas pantomime scene.

Robey's music hall act matured in the first decade of the 1900s, and he undertook several foreign tours. He starred in the Royal Command Performance in 1912 and regularly entertained before aristocracy. He was an avid sportsman, playing cricket and football at a semi-professional level. During the First World War, in addition to his performances in revues, he raised money for many war charities and was appointed a CBE in 1919. From 1918, he created sketches based on his Prime Minister of Mirth character and used a costume he had designed in the 1890s as a basis for the character's attire. He made a successful transition from music hall to variety shows and starred in the revue Round in Fifty in 1922, which earned him still wider notice. With the exception of his performances in revue and pantomime, he appeared as his Prime Minister of Mirth character in all the other entertainment media including variety, music hall and radio.[2]

In 1913 Robey made his film debut, but he had only modest success in the medium. He continued to perform in variety theatre in the inter-war years and, in 1932, starred in Helen!, his first straight theatre role. His appearance brought him to the attention of many influential directors, including Sydney Carroll, who signed him to appear on stage as Falstaff in Henry IV, Part 1 in 1935, a role that he later repeated in Laurence Olivier's 1944 film, Henry V. During the Second World War, Robey raised money for charities and promoted recruitment into the forces. By the 1950s, his health had deteriorated, and he entered into semi-retirement. He was knighted a few months before his death in 1954.

Biography

Early life

Robey was born at 334 Kennington Road, Kennington, London.[1][n 1] His father, Charles Wade,[6] was a civil engineer who spent much of his career on tramline design and construction. Robey's mother, Elizabeth Mary Wade née Keene, was a housewife; he also had two sisters.[1][n 2] His paternal ancestors originated from Hampshire; his uncle, George Wade, married into aristocracy in 1848, a link which provided a proud topic of conversation for future generations of the Wade family.[3] When Robey was five, his father moved the family to Birkenhead, where he helped in the construction of the Mersey Railway. Robey began his schooling in nearby Hoylake at a dame school.[1][8] Three years later the family moved back to London, near the border between Camberwell and Peckham. At around this time, trams were being introduced to the area, providing Charles Wade with a regular, well-paid job.[6]

To fulfil an offer of work,[9] Charles Wade moved the family to Germany in 1880, and Robey attended a school in Dresden.[8] He devoted his leisure hours to visiting the city's museums, art galleries and opera houses and gained a reasonable fluency in German by the time he was 12. He enjoyed life in the country and was impressed with the many operatic productions held in the city and with the Germans' high regard for the arts.[10] When he was 14, his father allowed him to move in with a clergyman's family in the German countryside, which he used as a base while studying science at Leipzig University.[11][12] To earn money, he taught English to his landlord's children and minded them while their parents were at work. Having successfully enrolled at the university, he studied art and music[13] and stayed with the family for a further 18 months so he could complete his studies before returning to England in 1885. He later claimed, apparently untruthfully, to have studied at the University of Cambridge.[10][n 3]

At the age of 18 Robey travelled to Birmingham, where he worked in a civil engineer's office. It was here that he became interested in a career on the stage and often dreamed of starring in his own circus.[15] He learned to play the mandolin and became a skilled performer on the instrument. This drew interest from a group of local musicians and, together with a friend from the group who played the guitar, Robey travelled the local area in search of engagements. Soon afterwards, they were hired to play at a charity concert at the local church, St Mary and St Ambrose in Edgbaston, a performance that led to more local bookings. For the next appearance, Robey performed an impromptu version of "Killaloo", a comic ditty taken from the burlesque Miss Esmeralda.[16] The positive response from the audience encouraged him to give up playing the mandolin to concentrate instead on singing comic songs.[17]

London debut

By 1890 Robey had become homesick, and so he returned to South London, where he took employment in a civil engineering company. He also joined a local branch of the Thirteen Club, whose members, many of whom were amateur musicians, performed in small venues across London.[n 4] Hearing of his talent, the founder of the club, W. H. Branch, invited Robey to appear at Anderton's Hotel in Fleet Street, where he performed the popular new comic song "Where Did You Get That Hat?". Robey's performance secured him private engagements for which he was paid a guinea a night.[17] By the early months of 1891, Robey was much in demand, and he decided to change his stage name. He swapped "Wade" for "Robey" after working for a company in Birmingham that bore the latter name.[17] It was at around this time that he met E. W. Rogers, an established music hall composer who wrote songs for Marie Lloyd and Jenny Hill. For Robey, Rogers wrote three songs: "My Hat's a Brown 'Un", "The Simple Pimple" and "It Suddenly Dawned Upon Me".[18]

In 1891 Robey visited the Royal Aquarium in Westminster where he watched "Professor Kennedy", a burlesque mesmerist from America.[18][19] After the performance, Robey visited Kennedy in his dressing room and offered himself as the stooge for his next appearance. They agreed that Robey, as his young apprentice, would be "mesmerised" into singing a comic song.[18] At a later rehearsal, Robey negotiated a deal to sing one of the comic songs that had been written for him by Rogers. Robey's turn was a great success, and as a result he secured a permanent theatrical residency at the venue.[20] Later that year, he appeared as a solo act at the Oxford Music Hall,[21] where he performed "The Simple Pimple" and "He'll Get It Where He's Gone to Now".[22] The theatrical press soon became aware of his act, and The Stage called him a "comedian with a pretty sense of humour [who] delivers his songs with considerable point and meets with all success".[23] In early 1892, together with his performances at the Royal Aquarium and the Oxford Music Hall, Robey starred alongside Jenny Hill, Bessie Bonehill and Harriet Vernon at the Paragon Theatre of Varieties in Mile End, where, according to his biographer Peter Cotes, he "stole the notices from experienced troupers".[2]

That summer, Robey conducted a music hall tour of the English provinces which began in Chatham and took him to Liverpool, at a venue owned by the mother of the influential London impresario Oswald Stoll. Through this engagement Robey met Stoll, and the two became lifelong friends.[2] In early December, Robey appeared in five music halls a night, including Gatti's Under the Arches, the Tivoli Music Hall and the London Pavilion. In mid-December, he travelled to Brighton, where he appeared in his first Christmas pantomime, Whittington Up-to-Date.[24] Pantomime would become a lucrative and regular source of employment for the comedian. Cotes calls Robey's festive performances the "cornerstone of his comic art", and the source of "some of his greatest successes".[24]

Music hall characterisations

During the 1890s Robey created music hall characters centred on everyday life. Among them were "The Chinese Laundryman" and "Clarence, the Last of the Dandies".[25] As Clarence, Robey dressed in a top hat and frock coat and carried a malacca cane, the garb of a stereotypical Victorian gentleman. For his drag pieces, the comedian established "The Lady Dresser", a female tailor who was desperate to out-dress her high class customers, and "Daisy Dillwater, the District Nurse" who arrived on stage with a bicycle to share light-hearted scandal and gossip with the audience before hurriedly cycling off.[26]

With Robey's popularity came an eagerness to differentiate himself from his music hall rivals, and so he devised a signature costume when appearing as himself: an oversized black coat fastened from the neck down with large, wooden buttons; black, unkempt, baggy trousers and a partially bald wig with black, whispery strands of unbrushed, dirty-looking hair that poked below a large, dishevelled top-hat.[2][n 5] He applied thick white face paint and exaggerated the redness on his cheeks and nose with bright red make-up; his eye line and eyebrows were also enhanced with thick, black greasepaint.[28] He held a short, misshaped, wooden walking stick, which was curved at the top. Robey later used the costume for his character, The Prime Minister of Mirth. The outfit helped Robey become instantly recognisable on the London music hall circuit.[2] He next made a start at building his repertoire and bought the rights to comic songs and monologues by several well-established music hall writers, including Sax Rohmer and Bennett Scott. For his routines, Robey developed a characteristic delivery described by Cotes as "a kind of machine-gun staccato rattle through each polysyllabic line, ending abruptly, and holding the pause while he fixed his audience with his basilisk stare."[29]

Success in pantomime and the provinces

At the start of 1894, Robey travelled to Manchester to participate in the pantomime Jack and Jill,[30][31] where he was paid £25 a week for a three-month contract.[30][n 6] He did not appear in Jack and Jill until the third act but pleased the holiday crowds nonetheless.[33] During one performance the scenery mechanism failed, which forced him to improvise for the first time. Robey fabricated a story that he had just dined with the Lord Mayor before detailing exactly what he had eaten. The routine was such a hit that it was incorporated into the show as part of the script.[34]

In the final months of 1894, Robey returned to London to honour a contract for Augustus Harris at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, the details of which are unknown.[24] In September he starred in a series of stand-up comedy shows that he would perform every September between 1894 and 1899. These short performances, in English seaside resorts including Scarborough and Bournemouth, were designed chiefly to enhance his name among provincial audiences.[35] For the 1895 and 1896 Christmas pantomimes, he appeared in Manchester and Birmingham, respectively, in the title role of Dick Whittington, for which he received favourable reviews and praise from audiences. Despite the show's success, Robey and his co-stars disliked the experience. The actress Ada Reeve felt that the production had a bad back-stage atmosphere and was thankful when the season ended,[36] while the comedian Barry Lupino was dismayed at having his role, Muffins, considerably reduced.[33]

On 29 April 1898, Robey married his first wife, the Australian-born musical theatre actress Ethel Hayden,[n 7] at St Clement Danes church in the Strand, London. The congregation was made up of various theatrical colleagues; J. Pitt Hardacre was his best man, and composer Leslie Stuart was the organist. Robey and Ethel resided briefly in Circus Road, St John's Wood, until the birth of their first child Edward in 1900.[37] They then moved to 83 Finchley Road in Swiss Cottage, Hampstead.[n 8] Family life suited Robey; his son Edward recalled many happy experiences with his father, including the evenings when he would accompany him to the half-dozen music halls at which he would be appearing each night.[39][n 9]

By the start of the new century, Robey was a big name in pantomime, and he was able to choose his roles. Pantomime enjoyed wide popularity until the 1890s, but by the time Robey had reached his peak, interest in it was on the wane. A type of character he particularly enjoyed taking on was the pantomime dame, which historically was played by comedians from the music hall.[41] Robey was inspired by the older comedians Herbert Campbell and Dan Leno, and, although post-dating them, he rivalled their eccentricity and popularity, earning the festive entertainment a new audience. In his 1972 biography of Robey, Neville Cardus thought that the comedian was "at his fullest as a pantomime Dame".[42]

In 1902 Robey created the character "The Prehistoric Man". He dressed as a caveman and spoke of modern political issues, often complaining about the government "slapping another pound of rock on his taxes".[25] The character was received favourably by audiences, who found it easy to relate to his topical observations.[25] That year he released "The Prehistoric Man" and "Not That I Wish to Say Anything" on shellac discs using the early acoustic recording process.[n 10]

Robey signed a six-year contract in June 1904 to appear annually at, among other venues, the Oxford Music Hall in London, for a fee of £120 a week. The contract also required him to perform during the spring and autumn seasons between 1910 and 1912. Robey disputed this part of the contract and stated that he agreed to this only as a personal favour to the music hall manager George Adney Payne and that it should have become void on Payne's death in 1907. The management of the Oxford counter-claimed and forbade Robey from appearing in any other music hall during this period. The matter went to court, where the judge found in Robey's favour.[45]

Robey was engaged to play the title role in the 1905 pantomime Queen of Hearts. The show was considered risqué by the theatrical press. In one scene Robey accidentally sat on his crown before bellowing "Assistance! Methinks I have sat upon a hedgehog"; in another sketch, the comedian mused, "Then there's Mrs Simkins, the swank! Many's the squeeze she's had of my blue bag on washing day."[46] Robey scored a further hit with the show the following year, in Birmingham, which Cotes describes as "the most famous of all famous Birmingham Theatre Royal pantomimes". Robey incorporated "The Dresser", a music hall sketch taken from his own repertoire, into the show.[47] Over the next few years he continued to tour the music hall circuit both in London and the English provinces[48] and recorded two songs, "What Are You Looking at Me For?" and "The Mayor of Mudcumdyke", which were later released by the Gramophone and Typewriter Company.[43]

Sporting interests and violin-making

Off-stage, Robey led an active lifestyle and was a keen amateur sportsman. He was proud of his healthy physique and maintained it by performing frequent exercise and following a careful diet. By the time he was in his mid-thirties, he had played as an amateur against Millwall, Chelsea and Fulham football clubs.[n 11] He organised and played in many charity football matches throughout England, which were described by the sporting press as being of a very high standard, and he remained an active football player well into his fifties.[50] Robey became associated with cricket by 1895 when he led a team of amateur players for a match at Turney Road in Dulwich.[51] In September 1904, while appearing in Hull, he was asked by the cricketer Harry Wrathall to take part in a charity cricket match at the Yorkshire County Cricket Club. Robey played so well that Wrathall asked him to return the following Saturday to take part in a professional game. That weekend, while waiting in the pavilion before the game, Robey was approached by an agent for Hull City A.F.C., who asked the comedian to play in a match that same afternoon. Robey agreed, swapped his cricket flannels for a football kit and played with the team against Nottingham Forest as an inside right.[52]

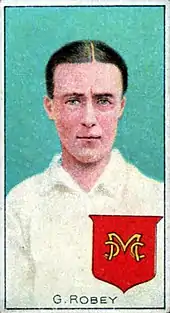

By 1903 Robey was playing at a semi-professional level. He was signed as an inside forward by Millwall Football Club and scored many goals for them.[53] He also displayed a good level of ability in vigoro,[54] an Australian sport derived from both cricket and baseball which was short-lived in England. Two years later he became a member of the Marylebone Cricket Club[55] and played in minor games for them for many years. He gained a reputation at the club for his comic antics on the field, such as raising his eyebrows at the approaching bowler in an attempt to distract him.[56] The writer Neville Cardus was complimentary about Robey's cricket prowess and called him "an elegant player" whose performances on the cricket field were as entertaining as they were on the stage.[55] Although a versatile player, Robey thought of himself as a "medium-paced, right-handed bowler".[57]

Robey was asked to help organise a charity football match in 1907 by friends of the Scottish football trainer James Miller, who had died the previous year. Robey compiled a team of amateur footballers from the theatrical profession and met Miller's former team Chelsea Football Club at their home ground. The match raised considerable proceeds for Miller's widow. Robey was proud of the match and joked: "I just wanted to make sure that Chelsea stay in the first division."[58][n 12]

In his spare time, Robey made violins, a hobby that he first took up during his years in Dresden. He became a skilled craftsman of the instrument, although he never intended for them to be played in public. Speaking in the 1960s, the violinist and composer Yehudi Menuhin, who played one of Robey's violins for a public performance during that decade, called the comedian's finished instrument "very professional". He was intrigued by the idea that a man as famous as Robey could produce such a "beautifully finished" instrument, unbeknown to the public.[59] Robey was also an artist, and some of his pen and ink self-caricatures are kept at the National Portrait Gallery, London.[60]

Oswald Stoll

Robey's first high-profile invitation came in the first decade of the 1900s from Hugh Lowther, 5th Earl of Lonsdale, who hired him as entertainment for a party he was hosting at Carlton House Terrace in Westminster. Soon afterwards, the comedian appeared for the first time before royalty when King Edward VII had Robey hired for several private functions. Robey performed a series of songs and monologues and introduced the "Mayor of Mudcumdyke", all of which was met with much praise and admiration from the royal watchers. He was later hired by Edward's son, the Prince of Wales (the future King George V), who arranged a performance at Carlton House Terrace for his friend Lord Curzon.[61]

In July 1912, at the invitation of the impresario Oswald Stoll, Robey took part for the first time in the Royal Command Performance,[62] to which Cotes attributes "one of the prime factors in his continuing popularity".[62] King George V and Queen Mary were "delighted" with Robey's comic sketch, in which he performed the "Mayor of Mudcumdyke" in public for the first time.[62] Robey found the royal show to be a less daunting experience than the numerous private command performances that he gave during his career.[61]

At the outbreak of the First World War, Robey wished to enlist in the army but, now in his 40s, he was too old for active service. Instead, he volunteered for the Special Constabulary and raised money for charity through his performances as a comedian. It was not uncommon for him to finish at the theatre at 1:00 am and then to patrol as a special constable until 6:00 am, where he would frequently help out during zeppelin raids. He combined his civilian duties with work for a volunteer motor transport unit towards the end of the war, in which he served as a lieutenant. He committed three nights a week to the corps while organising performances during the day to benefit war charities. Robey was a strong supporter of the Merchant Navy and thought that they were often overlooked when it came to charitable donations. He raised £22,000 at a benefit held at the London Coliseum, which he donated in the navy's favour.[63]

Film debut and The Bing Boys Are Here

Robey's first experience in cinema was in 1913, with two early sound film shorts: "And Very Nice Too" and "Good Queen Bess", made in the Kinoplasticon process, where the film was synchronised with phonograph records.[64][65] The next year, he tried to emulate his music hall colleagues Billy Merson and Charlie Austin, who had set up Homeland Films and found success with the Squibs series of films starring Betty Balfour.[66] Robey met filmmakers from the Burns Film Company, who engaged him in a silent short entitled "George Robey Turns Anarchist",[67] in which he played a character who fails to blow up the Houses of Parliament.[68] He continued to appear sporadically in film throughout the rest of his career, never achieving more than a modest amount of success.[69]

In 1914, for the first time in many years, Robey appeared in a Christmas pantomime as a male when he was engaged to play the title role in Sinbad the Sailor; Fred Emney Sr played the dame role. Although the critics were surprised by the casting, it appealed to audiences, and the scenes featuring Robey and Emney together proved the most memorable.[47] During the war the demand for light entertainment in the English provinces guaranteed Robey frequent bookings and a regular income.[70] His appearances in Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle and Glasgow were as popular as his annual performances in Birmingham. His wife Ethel accompanied him on these tours and frequently starred alongside him.[47]

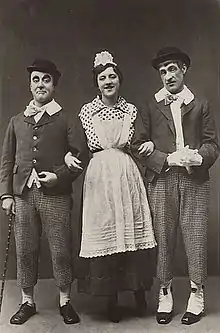

By the First World War, music hall entertainment had fallen out of favour with audiences. Theatrical historians blame the music hall's decline on the increasing salaries of performers and the halls' inability to present profitably the twenty or thirty acts that the audiences expected to see. Revue appealed to wartime audiences, and Robey decided to capitalise on the medium's popularity.[71] Stoll offered Robey a lucrative contract in 1916 to appear in the new revue The Bing Boys Are Here[72] at the Alhambra Theatre, London.[73] Dividing his time between three or four music halls a night had become unappealing to the comedian, and he relished the opportunity to appear in a single theatre.[74] He was cast as Lucius Bing opposite Violet Loraine, who played his love interest Emma, and the couple duetted in the show's signature song "If You Were the Only Girl (In the World)", which became an international success.[75][76]

This London engagement was a new experience for Robey, who had only been familiar with provincial pantomimes and week-long, one-man comedy shows. Aside from pantomime, he had never taken part in a long-running production,[77] and he had never had to memorise lines precisely or keep to schedules enforced by strict directors and theatre managers.[70] The Bing Boys Are Here ran for 378 performances and occupied the Alhambra for more than a year. The theatrical press praised Robey as "the first actor of the halls".[34] He made two films towards the end of the war: The Anti-frivolity League in 1916[78] and Doing His Bit the following year.[79]

Zig-Zag to Joy Bells

Robey left the cast of The Bing Boys during its run, in January 1917, to star at the London Hippodrome in Albert de Courville, Dave Stamper and Gene Buck's lavishly staged revue Zig-Zag!.[80] Robey included a sketch based on his music hall character "The Prehistoric Man", with Daphne Pollard playing the role of "She of the Tireless Tongue".[81] In another scene, he played a drunken gentleman who accidentally secures a box at the Savoy Theatre instead of an intended hotel room. The audience appeared unresponsive to the character, so he changed it mid-performance to that of a naive Yorkshire man. The change provoked much amusement, and it became one of the most popular scenes of the show.[80] Zig-Zag ran for 648 performances.[81] Stoll again secured Robey for the Alhambra in 1918 for a sequel, The Bing Boys on Broadway. The show, again co-starring Violet Loraine, matched the popularity of its predecessor and beat the original show's run with a total of 562 performances.[81]

Robey returned to the London Hippodrome in 1919 where he took a leading role in another hit revue, Joy Bells. Phyllis Bedells took over from Pollard as his stage partner, with Anita Elson and Leon Errol as supporting dancers. Robey played the role of an old-fashioned father who is mystified over the changing traditions after the First World War. He interpolated two music hall sketches: "No, No, No" centred on turning innocent, everyday sayings into suggestive and provocative maxims, and "The Rest Cure" told the story of a pre-op hospital patient who hears worrying stories of malpractice from his well-meaning friends who visit him.[82] In the Italian newspaper La Tribuna, the writer Emilio Cecchi commented: "Robey, just by being Robey, makes us laugh until we weep. We do not want to see either Figaro or Othello; it is quite enough for Robey to appear in travelling costume and to turn his eyes in crab-like fashion from one side of the auditorium to another. Robey's aspect in dealing with his audience is paternal and, one might say, apostolic."[83] Joy Bells ran for 723 performances.[70]

In the early months of 1919, Robey completed a book of memoirs, My Rest Cure, which was published later that year.[84] During the run of Joy Bells he was awarded the Legion of Honour for raising £14,000 for the French Red Cross.[70] He declined a knighthood that same year because, according to Cotes, he was worried that the title would distance him from his working-class audiences;[85][86] he was appointed a CBE by George V at Buckingham Palace instead.[87] On the morning of the penultimate Joy Bells performance, Robey was invited to Stoll's London office, where he was offered a role in a new revue at the Alhambra Theatre. On the journey, he met the theatre impresario Sir Alfred Butt, who agreed to pay him £100 more, but out of loyalty to Stoll, he declined the offer and resumed his £600 a week contract at the Alhambra.[88] On 28 July 1919, Robey took part in his second Royal Command Performance, at the London Coliseum. He and Loraine sang "If You Were the Only Girl (In the World)".[89]

Films and revues of the early 1920s

A gap in the Alhambra's schedule allowed Stoll to showcase Robey in a new short film.[90][91] "George Robey's Day Off" (1919) showed the comedian acting out his daily domestic routines to comic effect,[92] but the picture failed at the box office. The British director John Baxter concluded that producers did not know how best to apply Robey's stage talents to film.[66][93]

By 1920 variety theatre had become popular in Britain,[94] and Robey had completed the successful transition from music hall to variety star. Pantomime, which relied on its stars to make up much of the script through ad lib, was also beginning to fall out of favour, and his contemporaries were finding it too difficult to create fresh material for every performance; for Robey, however, the festive entertainment continued to be a lucrative source of employment.[95][96]

Robey's first revue of the 1920s was Johnny Jones, which opened on 1 June 1920 at the Alhambra Theatre. The show also featured Ivy St. Helier, Lupino Lane and Eric Blore[97] and carried the advertisement "A Robey salad with musical dressing".[91] One of the show's more popular gags was a scene in which Robey picked and ate cherries off St. Helier's hat, before tossing the stones into the orchestra pit which were then met by loud bangs from the bass drum.[97][n 13] A sign of his popularity came in August 1920 when he was depicted in scouting costume for a series of 12 Royal Mail stamps in aid of the Printers Pension Corporation War Orphans and the Prince of Wales Boy Scout Funds.[98][99]

– Neville Cardus, The Darling of the Halls (1972)[100]

The revue Robey en Casserole (1921) was next for Robey, during which he led a troupe of dancers in a musical piece called the "Policemen Ballet". Each dancer was dressed in a mock police uniform on top and a tutu below. The show was the first failure for the comedian under Stoll's management. That December Robey appeared in his only London pantomime, Jack and the Beanstalk, at the Hippodrome.[97][101] His biographer, Peter Cotes, remembered the comedian's interpretation of Dame Trot as "enormously funny: a bucolic caricature of a woman, sturdy and fruity, leathery and forbidding" and thought that Robey's comic timing was "in a class of its own."[34][n 14] In March 1922 Robey remained at the Hippodrome in the revue Round in Fifty, a modernised version of Round the World in Eighty Days, which proved to be another hit for the London theatre, and a personal favourite of the comedian.[97][n 15]

Marriage breakdown and foreign tours

Stoll brought Robey to cinema audiences a further four times during 1923. The first two films were written with the intention of showcasing the comedian's pantomime talents: One Arabian Night was a reworking of Aladdin and co-starred Lionelle Howard and Edward O'Neill,[104] while Harlequinade visited the roots of pantomime.[66][105] One of Robey's more notable roles under Stoll was Sancho Panza in Maurice Elvey's 1923 film Don Quixote,[106] for which he received a fee of £700 a week.[93] The amount of time he spent working away from home led to the breakdown of his marriage, and he separated from Ethel in 1923.[38] He had a brief affair with one of his leading ladies and walked out of the family home.[37]

Robey made a return to the London Hippodrome in 1924 in the revue Leap Year in which he co-starred with Laddie Cliff, Betty Chester and Vera Pearce. Leap Year was set in South Africa, Australia and Canada, and was written to appeal to the tourists who were visiting London from the Commonwealth countries. Robey was much to their tastes, and his rendition of "My Old Dutch" helped the show achieve another long run of 421 performances. Sky High was next and opened at the London Palladium in March 1925. The chorus dancer Marie Blanche was his co-star, a partnership that caused the gossip columnists to comment on the performers' alleged romance two years previously. Despite the rumours Blanche continued as his leading lady for the next four years, and Sky High lasted for 309 performances on the West End stage.[107]

The year 1926 was lacking in variety entertainment, a fact largely attributed to the UK general strike that had occurred in May of that year.[107] The strike was unexpected by Robey, who had signed the previous year to star in a series of variety dates for Moss Empires. The contract was lucrative, made more so by the comedian's willingness to manage his own bookings. He took the show to the provinces under the title of Bits and Pieces and employed a company of 25 artists as well as engineers and support staff. Despite the economic hardships of Britain in 1926, large numbers of people turned out to see the show.[108] He returned to Birmingham, a city where he was held in great affection, and where he was sure the audiences would embrace his new show. However, censors demanded that he omit the provocative song "I Stopped, I Looked, I Listened" and that he heavily edit the sketch "The Cheat". The restrictions failed to dampen the audiences' enthusiasm, and Bits and Pieces enjoyed rave reviews. It ran until Christmas and earned a six-month extension.[108]

In the spring of 1927 Robey embraced the opportunity to tour abroad, when he and his company took Bits and Pieces to South Africa, where it was received favourably.[108] By the time he had left Cape Town, he had played to over 60,000 people and had travelled in excess of 15,000 miles.[109][n 16] Upon his return to England in October, he took Bits and Pieces to Bradford.[110] In August 1928, Robey and his company travelled to Canada, where they played to packed audiences for three months.[111] It was there that he produced a new revue, Between Ourselves, in Vancouver,[112][113] which was staged especially for the country's armed forces.[111] The Canadians were enthusiastic about Robey; he was awarded the freedom of the city in London, Ontario, made a chieftain of the Sarcee tribe,[n 17] and was an honorary guest at a cricket match in Edmonton, Alberta.[111] He described the tour as "one of unbroken happiness."[111] In the late 1920s Robey also wrote and starred in two Phonofilm sound-on-film productions, Safety First (1928) and Mrs. Mephistopheles (1929).[64]

In early 1929 Robey returned to South Africa and then Canada for another tour with Bits and Pieces, after which he started another series of variety dates back in England. Among the towns he visited was Woolwich, where he performed to packed audiences over the course of a week.[112] Here he met the theatre managers Frank and Agnes Littler,[n 18] with the latter briefly becoming his manager.[112][113] In 1932 Robey appeared in his first sound film, The Temperance Fête,[115] and followed this with Marry Me, which was, according to his biographer A. E. Wilson, one of the most successful musical films of the comedian's career.[93] The film tells the story of a sound recordist in a gramophone company who romances a colleague when she becomes the family housekeeper.[116]

By the later months of 1932, Robey had formed a romantic relationship with the Littlers' daughter Blanche (1897–1981), who then took over as his manager. The couple grew close during the filming of Don Quixote, a remake of the comedian's 1923 success as Sancho Panza. Unlike its predecessor, Don Quixote had an ambitious script, big budget and an authentic foreign setting.[n 19] Robey resented having to grow a beard for the role and disliked the French climate and gruelling 12-week filming schedule.[118] He refused to act out his character's death scene in a farcical way and also objected to the lateness of the "dreadfully banal" scripts,[n 20] which were often written the night before filming.[119]

Venture into legitimate theatre

Until 1932 Robey had never played in legitimate theatre, although he read Shakespeare from an early age.[120] That year he took the part of King Menelaus in Helen!,[121] which was an English-language adaptation by A. P. Herbert of Offenbach's operetta La belle Hélène. The show's producer C. B. Cochran, a longstanding admirer of Robey, engaged a prestigious cast for the production, including Evelyn Laye and W. H. Berry, with choreography by Léonide Massine and sets by Oliver Messel. The operetta opened on 30 January 1932, becoming the Adelphi Theatre's most successful show of the year.[122] The critic Harold Conway wrote that while Robey had reached the pinnacle of his career as a variety star, which only required him to rely on his "breezy, cheeky personality", he had reservations about the comedian's ability to "integrate himself with the other stars ... to learn many pages of dialogue, and to remember countless cues."[123]

After the run of Helen!, Robey briefly resumed his commitments to the variety stage before signing a contract to appear at the Savoy Theatre as Bold Ben Blister in the operetta Jolly Roger, which premiered in March 1933. The production had a run of bad luck, including an actors' strike which was caused by Robey's refusal to join the actors' union Equity. The dispute was settled when he was included as a co-producer of the show, thus excluding him as a full-time actor.[124] Robey made a substantial donation to the union, and the production went ahead.[125] Despite its troubles, the show was a success and received much praise from the press. Harold Conway of the Daily Mail called the piece "one of the outstanding triumphs of personality witnessed in a London theatre".[126] Later that year, Robey completed his final autobiography, Looking Back on Life. The literary critic Graham Sutton admired Robey for his honest and frank account, and thought that he was "at his best when most personal".[127][128]

Shakespearean roles

According to Wilson, Robey revered Shakespeare and had an "excellent reading knowledge of the Bard" even though the comedian had never seen a Shakespeare play. As a child, he had committed to memory the "ghost" scene in Hamlet.[129] Writing in 1933, Cochran expressed the opinion that Robey had been a victim of a largely conservative and "snobbish" attitude from theatre managers, that the comedian was "cut out for Shakespeare", and that if he had been frequently engaged in playing the Bard's works, then "Shakespeare would probably have been popular."[130] In 1934, the theatre director Sydney Carroll offered Robey the chance to appear as Nick Bottom in A Midsummer Night's Dream at the Open Air Theatre, Regent's Park, but he initially declined the offer, citing a hectic schedule,[131] including a conflict with his appearance in that year's Royal Variety Performance on 8 May.[89] He was also concerned that he would not be taken seriously by legitimate theatre critics and knew that he would not be able to include a comic sketch or to engage in his customary resourceful gagging.[131] In the same year, Robey starred in a film version of the hit musical Chu Chin Chow. The New York Times called him "a lovable and laughable Ali Baba".[132]

At the start of 1935 Robey accepted his first Shakespearean role, as Falstaff in Henry IV, Part 1, which surprised the press and worried fans who thought that he might retire the Prime Minister of Mirth. The theatrical press were sceptical of a music hall performer taking on such a distinguished role; Carroll, the play's producer, vehemently defended his casting choice.[133] Carroll later admitted taking a gamble on employing Robey but wrote that the comedian "has unlimited courage in challenging criticism and risking his reputation on a venture of this kind; he takes both his past and his future in both hands and is faced with the alternative of dashing them into the depths or lifting them to a height hitherto undreamt of."[134] Carroll further opined that "[Robey] has never failed in anything he has undertaken. He is one of the most intelligent and capable of actors."[135]

Henry IV, Part I opened on 28 February at Her Majesty's Theatre, and Robey proved himself to be a capable Shakespearean actor,[136] though his Shakespearean debut was marred initially by an inability to remember his lines. A journalist from The Daily Express thought that Robey seemed uncomfortable, displayed a halting delivery and was "far from word perfect".[137] Writing in The Observer, the critic Ivor Brown said of Robey's portrayal: "In no performance within my memory has the actor been more obviously the afflicted servant of his lines and more obviously the omnipotent master of the situation".[138] Another journalist, writing in the Daily Mirror, thought that Robey "gave 25 percent of Shakespeare and 75 percent of himself".[139]

In any case, such was Robey's popularity in the role that the German theatre and film producer Max Reinhardt declared that, should the opportunity arise for a film version, the comedian would be his perfect choice as Falstaff. Cotes described Robey as having "a great vitality and immense command of the [role]. He never faltered, he had to take his audience by the throat and make them attentive at once because he couldn't play himself in."[140] Although he was eager to be taken seriously as a legitimate actor, Robey provided a subtle nod in the direction of his comic career by using the wooden cane intended for the Prime Minister of Mirth for the majority of his scenes as Falstaff.[141] The poet John Betjeman responded to the critics' early scepticism: "Variety artistes are a separate world from the legitimate stage. They are separate too, from ballet, opera, and musical comedy. It is possible for variety artists to appear in all of these. Indeed, no one who saw will ever forget the superb pathos and humour of George Robey's Falstaff".[142] Later, in 1935, Blanche Littler persuaded Robey to accept Carroll's earlier offer to play Bottom, and the comedian cancelled three weeks' worth of dates. The press were complimentary of his performance, and he later attributed his success to Littler and her encouragement.[131]

Radio and television

Robey was interviewed for The Spice of Life programme for the BBC in 1936. He spoke about his time spent on the music hall circuit, which he described as the "most enjoyable experience" of his life. The usually reserved Robey admitted that privately he was not a sociable person and that he often grew tired of his audiences while performing on stage, but that he got his biggest thrill from making others laugh. He also declared a love for the outdoors[143] and mentioned that, to relax, he would draw "comic scribbles" of himself as the Prime Minister of Mirth, which he would occasionally give to fans.[60] As a result of the interview he received more than a thousand fan letters from listeners. Wilson thought that Robey's "perfect diction and intimate manner made him an ideal broadcast speaker".[143] The press commented favourably on his performance, with one reporter from Variety Life writing: "I doubt whether any speaker other than a stage idol could have used, as Robey did, the first person singular almost incessantly for half an hour without causing something akin to resentment. ... The comedian's talk was brilliantly conceived and written."[144][n 21]

In the later months of 1936, Robey repeated his radio success with a thirty-minute programme entitled "Music-Hall", recorded for American audiences, to honour the tenth birthday of the National Broadcasting Corporation. In it, he presented a montage of his characterisations as well as impressions of other famous acts of the day. A second programme, which he recorded the following year, featured the comedian speaking fondly of cricket and of the many well-known players whom he had met on his frequent visits to the Oval and Lord's cricket grounds over his fifty-year association.[146]

In the summer of 1938 Robey appeared in the film A Girl Must Live, directed by Carol Reed, in which he played the role of Horace Blount.[147] A report in the Kinematograph Weekly commented that the 69-year-old comedian was still able to "stand up to the screen by day and variety by night."[148] A journalist for The Times opined that Robey's performance as an elderly furrier, the love interest of both Margaret Lockwood and Lilli Palmer, was "a perfect study in bewildered embarrassment".[149]

Robey made his television debut in August 1938[150] but was unenthused with the medium and only made rare appearances. The BBC producer Grace Wyndham Goldie was dismayed at how little of his "comic quality" was conveyed on the small screen. Goldie thought that Robey's comic abilities were not limited to his voice and depended largely on the relation between his facial expressions and his witty words. She felt that he should "be forbidden, by his own angel, if nobody else, to approach the ordinary microphone". Nonetheless, Goldie remained optimistic about Robey's future television career.[151] The journalist L. Marsland Gander disagreed and thought that Robey's methods were "really too slow for television".[151]

That November, and with his divorce from Ethel finalised,[152] Robey married Blanche Littler, who was more than two decades his junior,[153] at Marylebone Town Hall.[154] At Christmas, he fractured three ribs and bruised his spine when he accidentally fell into the orchestra pit while appearing in the 1938–39 pantomime Robinson Crusoe in Birmingham.[155] He attributed the fall to his face mask which gave him a limited view of the stage. The critic Harold Conway was less forgiving, blaming the accident on the comedian's "lost self-confidence" and opining that the accident was the start of Robey's professional decline.[156]

Second World War

Aware of demand for his act in Australia, Robey conducted a second tour of the country at the start of 1939. While he was appearing at the Tivoli Theatre in Sydney, war broke out with Germany. Robey returned to England and concentrated his efforts on entertaining to raise money for the war effort.[157] He signed up with the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) for whom he appeared in a wide range of shows and also in his own one-man engagements. He would sometimes turn up unannounced to perform at hospitals, munition factories, airfields, anti-aircraft posts and other venues where there was an audience of just a few people.[158]

During the 1940s, Robey appeared predominantly in troop concerts as himself[115] but caused controversy by jokingly supporting the Nazis and belittling black people during his act. His intentions were to gently poke fun at the "Little Englanders", but audiences thought that he was sympathising with Nazism. His jocular view that a defeat for Hitler would mean a victory for bolshevism was highlighted in a series of controversial interviews, which caused him much embarrassment when challenged and which he regretted afterwards. His views became known in the press as "Robeyisms", which drew increasing criticism, but his Prime Minister of Mirth remained popular, and he used the character to divert the negative publicity.[159] Cotes wrote that Robey was not a politician, merely a jingoist, who "lived long enough to feel [that] his little-Englander outlook [was causing him] acute embarrassment, and his army of admirers deep dismay."[158]

Robey starred in the film Salute John Citizen in 1942, directed by Maurice Elvey and co-starring Edward Rigby and Stanley Holloway, about the effects that the war had on a normal British family.[160] In a 1944 review of the film, Robey was described as being "convincing in [an] important role" but the film itself had "dull moments in the simple tale".[161] That Christmas, Robey travelled to Bristol, where he starred in the pantomime Robinson Crusoe.[115] A further four films followed in 1943, one of which promoted war propaganda while the other two displayed the popular medium of cine-variety.[162][n 22] Cine-variety introduced Robey to the Astoria in Finsbury Park, London, a venue which was used to huge audiences and big-name acts and was described as "a super-cinema".[164]

During the early months of 1944, Robey returned to the role of Falstaff when he appeared in the film version of Henry V, produced by Eagle-Lion Films. The American film critic Bosley Crowther had mixed opinions of the film. Writing in The New York Times in 1946, he thought that it showcased "a fine group of British film craftsmen and actors", who contributed to "a stunningly brilliant and intriguing screen spectacle". Despite that, he considered the film's additional screenplay poor and called Falstaff's deathbed scene "non-essential and just a bit grotesque."[165] Late in 1944, he appeared in Burnley in a show entitled Vive Paree alongside Janice Hart and Frank O'Brian.[166] In 1945, Robey starred in two minor film roles, as "Old Sam" in The Trojan Brothers, a short comedy film in which two actors experience various problems as a pantomime horse,[167] and as "Vogel" in the musical romance Waltz Time.[168] He spent 1947 touring England,[169] while the following spring he undertook a provincial tour of Frederick Bowyer's fairy play The Windmill Man, which he also co-produced with his wife.[170]

Decline in health

In June 1951, now aged 81, Robey starred in a midnight gala performance at the London Palladium in aid of the family of Sid Field who had died that year. For the finale, Robey performed "I Stopped, I Looked, I Listened" and "If You Were the Only Girl in the World"; the rest of the three-hour performance featured celebrities from the radio, television and film mediums.[171] The American comedian Danny Kaye, who was also engaged for the performance, called Robey a "great, great artist".[172][n 23] The same month, Robey returned to Birmingham, where he opened a garden party at St. Mary and St. Ambrose Church, a venue in which he had appeared at the beginning of his career. On 25 September he appeared for the BBC on an edition of the radio series Desert Island Discs for which he chose among others "Mondo ladro", Falstaff's rueful complaint about the wicked world in Verdi's opera Falstaff.[174][n 24] For the rest of the year Robey made personal appearances opening fetes and attending charity events.[173]

Robey took part in the Festival of Variety for the BBC in 1951,[175] which paid tribute to the British music hall. For his performance, he adopted an ad-lib style rather than use a script.[173] His wife sat at the side of the stage, ready to provide support should he need it. According to Wilson, Robey's turn earned the loudest applause of the evening.[176] The following month Robey undertook a long provincial tour in the variety show Do You Remember? under the management of Bernard Delfont. After an evening's performance in Sheffield, he was asked by a local newspaper reporter if he considered retiring. The comedian quipped: "Me retire? Good gracious, I'm too old for that. I could not think of starting a new career at my age!"[177] In December, he opened the Lansbury Lodge home for retired cricketers in Poplar, East London; he considered the ceremony to be one of the "happiest memories of his life."[178]

By early 1952, Robey was becoming noticeably frail, and he lost interest in many of his sporting pastimes. Instead, he stayed at home and drew comic sketches featuring the Prime Minister of Mirth.[179] In May he filmed The Pickwick Papers, in which he played the role of old Tony Weller, a part which he had initially turned down on health grounds.[180] The following year, and in aid of the games fund, he starred as Clown in a short pantomime at the Olympic Variety Show at the Victoria Palace Theatre. Organisers asked for him to appear in the Prime Minister of Mirth costume instead of the usual clown garb, a request the comedian was happy to fulfil.[181]

Knighthood and death

In the early months of 1954, a knighthood was conferred on Robey by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother at Buckingham Palace.[182] During the following weeks, his health declined; he became confined to a wheelchair and spent the majority of his time at home under the care of his wife. In May he opened a British Red Cross fete in Seaford, East Sussex, and, a month later, made his last public appearance, on television as a panellist in the English version of The Name's the Same. Wilson called Robey's performance "pathetic" and thought that he appeared with only "a hint of his old self".[183] By June he had become housebound and quietly celebrated his 85th birthday surrounded by family; visiting friends were organised into appointments by his wife Blanche, but theatrical colleagues were barred in case they caused the comedian too much excitement.[184]

Robey suffered a stroke on 20 November and remained in a semi-coma for just over a week. He died on 29 November 1954 at his home in Saltdean, East Sussex,[185][186] and was cremated at the Downs Crematorium in Brighton.[187] Blanche continued to live on the Sussex coast until her death at the age of 83 in 1981.[188]

Tributes and legacy

News of Robey's death prompted tributes from the press, who printed illustrations, anecdotes and reminders of his stage performances and charitable activities. "Knighthood notwithstanding, George Robey long ago made himself a place as an entertainer and artist of the people", declared a reporter from the Daily Worker,[189] while a critic for the Daily Mail wrote: "Personality has become a wildly misused word since his heyday, but George Robey breathed it in every pore."[190] In Robey's obituary in The Spectator, Compton Mackenzie called the comedian "one of the last great figures of the late Victorian and Edwardian music-hall."[191]

In December 1954, a memorial service for Robey was held at St Paul's Cathedral. The diverse congregation consisted of royalty, actors, hospital workers, stage personnel, students and taxi drivers, among others. The Bishop of Stepney, Joost de Blank, said: "We have lost a great English music hall artist, one of the greatest this country has known in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries."[192] Performers gave readings at the service, including the comedian Leslie Henson, who called Robey "that great obstinate bullock of variety".[21] In his lifetime, Robey helped to earn more than £2,000,000 for charitable causes, with £500,000 of that figure being raised during the First World War.[85][193] In recognition of his efforts, the Merchant Seaman's Convalescent Home in Limpsfield, Surrey, named a ward after him, and managerial staff at the Royal Sussex Hospital later bought a new dialysis machine in his memory.[194]

Robey's comic delivery influenced other comedians, but opinions of his effectiveness as a comic vary. The radio personality Robb Wilton acknowledged learning a lot from him, and although he felt that Robey "was not very funny", he could time a comic situation perfectly.[35] Similarly, the comedian Charlie Chester admitted that, as a comedian, Robey "still didn't make me laugh," although he described him as "a legend" whose Prime Minister of Mirth character used a beautiful make-up design.[195] Robey's biographer Peter Cotes disagreed with these assessments, praising the comedian's "droll like humour" and comparing it in greatness to Chaplin's miming and Grock's clowning.[196] Cotes wrote: "His Mayor, Professor of Music, Saracen, Dame Trot, Queen of Hearts, District Nurse, Pro's Landlady, and of course his immortal Prime Minister, were all absurdities: rich, outsize in prim and pride, gloriously disapproving bureaucratic petty officialdom at its worst, best and funniest."[197]

Violet Loraine called her former co-star "one of the greatest comedians the world has ever known",[198] while the theatrical producer Basil Dean opined that "George was a great artist, one of the last and [sic] the really big figures of his era. They don't breed them like that now."[198] The actor John Gielgud, who remembered meeting Robey at the Alhambra Theatre in 1953, called the comedian "charming, gracious [and] one of the few really great ones" of the music hall era.[198] Upon his death, Robey's costume for the Prime Minister of Mirth was donated to the London Museum, where it is on permanent display.[194]

Notes and references

Notes

- Robey would later claim that he was born in the more affluent area of Herne Hill, although this was incorrect. His birthplace in Kennington is a three-storey house above a shop, which was then a hardware outlet owned by William Brown.[3] In the 1860s, Kennington Road was a wealthy area mainly inhabited by successful tradesmen and businessmen. By the 1880s, the area had fallen into a decline and was considered by locals to be one of the most impoverished areas in London.[4] The comedian Charlie Chaplin, who had a poor and deprived upbringing, was born in the same street 18 years after Robey.[5]

- Robey's parents each died during the First World War; his father of a heart attack and his mother as a result of an injury she had sustained during an air raid.[7]

- Robey's time at Leipzig University was cut short as his father had to return to England to work. There is no evidence that Robey enrolled at Cambridge or any other English university as fees in Victorian England were too expensive for someone like Charles Wade.[14] Members of the theatrical community were convinced of his attendance at Cambridge.[10] The theatre critic Max Beerbohm wrote that Robey was one of the few distinguished men to emerge from the campus, but the English writer Neville Cardus was more sceptical, wondering how someone from the University of Cambridge could end up in the music hall.[14] Robey's biographer, Peter Cotes, concludes that he likely played along with the assumptions that he was a Cambridge graduate to fit in with the higher circles of society.[10]

- Founded by W. H. Blanch, the Thirteen Club charged members a fee of half a crown a year. The club members, including both amateur and professional performers, were devoted to the idea of flouting superstition while staging concerts in public houses and halls across London.[17]

- He swapped the top hat for a small bowler in 1924.[27]

- Robey considered the fee to be generous. Cecilia Loftus, a well-established music hall performer, was paid £80 a week for an engagement that year.[32]

- Ethel Hayden was born in Melbourne in 1877. She arrived in London at an early age and was starring in The Circus Girl at the Gaiety Theatre at the time of her marriage to Robey.[37] A star in her own right, Ethel often accompanied her husband on stage in his various pantomimes and music hall sketches.[38]

- Swiss Cottage now forms part of the London Borough of Camden.

- Edward showed some talent for the stage and appeared in a few minor roles as a child. He gave up acting in his teenage years.[37] He studied law at the University of Cambridge and then with the barrister Edward Marshall Hall, who sponsored him when he came to the bar in 1925. Edward became the Chief Prosecutor in the John George Haigh case; was a member of the British legal team at the Nuremberg war trials and was appointed a Metropolitan Magistrate in 1954.[40]

- The songs were released by the Gramophone and Typewriter Company,[43] one of the early recording companies, which became the parent organisation for the His Master's Voice (HMV) label.[44]

- In 1912 Robey wrote a story entitled Football in the Year 2000 for Fulham Football Club's in-house magazine in which he predicted that players would be flown to matches and paid in tobacco and would be influential in stopping wars and resolving national rivalries.[49]

- In the later months of 1908, while appearing as Dame Trot in Jack and the Beanstalk in Birmingham, Robey ran the quickest time in both the 100 and 220-yard sprint at a track in Small Heath.[56]

- The show featured the songs "It Wouldn't Surprise Me a Bit" and "A Little House, A Little Home".[91]

- The production also featured Clarice Mayne as Jack. Jay Laurier and Tom Walls warmed the audience before the main performance.[102]

- Written by Sax Rohmer and Julian and Laurie Wylie, Round in Fifty told the story of Phileas Fogg, who travelled the world for a bet. The revue featured a musical score by James Tate and Herman Finck and was one of the first productions to feature an accompanying projected film sequence (it showed Phileas racing an Atlantic liner in a motor boat). Co-stars included Wallace and Barry Lupino and Alec Kellaway. It ran for 471 performances.[103]

- 15,000 miles (24,000 km)

- During the elaborate ceremony, Robey was given an eagle-feathered head-dress and the tribal name of "Dit-ony-Chusaw", which translates to "Chief Eagle Plume".[111]

- Frank Rolison Littler (1879–1940) married Agnes Richeux, the widow of the impresario Jules Richeux, in 1914. The three children from the Richeux marriage all adopted the surname "Littler", and the two sons, Prince Littler and Emile, both became well-known impresarios.[114]

- The 1932 version was filmed in Grasse in the south of France. The earlier film was shot in Cumberland; Robey was in the English-language version, one of three versions.[117]

- In the opinion of Wilson, p. 155

- Wilson states that the occasion was Robey's broadcast debut, but Robey had appeared on radio from time to time since at least 1925.[145]

- Cine-variety achieved popularity in the 1920s and incorporated the talking motion picture with variety theatre. Many variety theatres were converted into cinemas and showcased the talents of variety comedians, which bought them to a wider audience.[163]

- Other participants included Vivien Leigh, Laurence Olivier, Tommy Trinder and the Crazy Gang.[173]

- Robey's other choices for the programme were: 1. Tchaikovsky – Nutcracker Suite: "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy". 2. Noël Coward – "I'll See You Again". 3. Grieg – "Piano Concerto in A Minor". 4. Gilbert and Sullivan – The Gondoliers. 5. Fritz Kreisler – "Liebesfreud". 6. Ivor Novello – Glamorous Night. 7. Elgar – "Land of Hope and Glory".[174]

References

- Harding, James. "Robey, George", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed 10 May 2014. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Cotes, p. 42.

- Cotes, p. 16.

- Cotes, pp. 16–17.

- Cotes, p. 17.

- Cotes, p. 18.

- Wilson, p. 38.

- Cotes, p. 19.

- Wilson, pp. 25–26.

- Cotes, p. 20.

- Cotes, pp. 19–20.

- Wilson, p. 26.

- Baker, p. 272.

- Cotes, p. 21.

- Cotes, p. 22.

- Cotes, p. 23.

- Cotes, p. 24.

- Cotes, p. 25.

- The Royal Aquarium (Arthur Lloyd theatre history), accessed 26 May 2008.

- Cotes, pp. 25–26.

- Cotes, p. 6.

- Cotes, pp. 13–14.

- "Mr George Robey", The Stage, 22 October 1891, p. 4.

- Cotes, p. 41.

- Cotes, p. 51.

- Cotes, pp. 52–53.

- Cotes, p. 105.

- Cotes, p. 14.

- Cotes, p. 43.

- Cotes, pp. 66–67.

- "A Theatre Case". West Gippsland Gazette (242). Victoria, Australia. 27 January 1903. p. 4 (morning). Retrieved 18 May 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Maloney, "The Scottish 'pro's", p. 106.

- Cotes, p. 67.

- Cotes, p. 70.

- Cotes, p. 47.

- Reeve, Ada. Quoted in Cotes, p. 67.

- Cotes, p. 58.

- Cotes, p. 59.

- Cotes, pp. 58–59.

- Cotes, p. 62.

- Cotes, p. 63.

- Cardus, Neville. Quoted in Cotes, p. xi.

- "George Robey – WINDYCDR17 – The Prime Minister of Mirth", Windyridge Music Hall CDs, accessed 24 February 2014.

- "Columbia Graphophone-H.M.V. Merger In England by Morgan Deal Indicated", The New York Times, 27 April 1930.

- "Comedian's £200 a Week". The Register (Adelaide). LXXV (19, 774). South Australia. 29 March 1910. p. 3. Retrieved 18 May 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Cotes, p. 69.

- Cotes, p. 68.

- Cotes, p. 192.

- Horrall, "Football", p. 163

- Cotes, p. 136.

- "E Swanborough's XI v G Robey's XI", Cricket Archive, accessed 15 April 2014.

- Wilson, p. 108.

- Wilson, p. 103.

- Cotes, p. 140.

- Cotes, p. 138.

- Cotes, p. 139.

- Robey, George. Quoted in Cotes, p. 139.

- Cotes, p. 137.

- Cotes, p. 153.

- "George Robey (1869–1954), Comedian", National Portrait Gallery, accessed 8 May 2014.

- Cotes, p. 75.

- Cotes, p. 48.

- Cotes, p. 80.

- "George Robey", Osobnosti.cz, accessed 2 June 2014

- Parrill, "'Good Queen Bess' (1913)", p. 91

- Cotes, p. 104.

- George Robey Turns Anarchist, British Film Institute, accessed 1 February 2014.

- St. Pierre, p. 37.

- Cotes, p. 102.

- Cotes, p. 82.

- Wilson, p. 109.

- Cotes, pp. 83–85.

- Cotes, p. 195.

- Wilson, p. 110.

- "The Bing Boys Are Here", Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 1 May 1916, p. 2.

- Fazan, p. 30.

- Cotes, p. 83.

- The Anti-frivolity League, British Film Institute, accessed 1 February 2014.

- Doing His Bit, British Film Institute, accessed 1 February 2014.

- Stone, p. 27.

- Cotes, p. 85.

- Stone, p. 28.

- Cecchi, Emilio. La Tribuna, quoted in Wilson, p. 111.

- Robey, George. My Rest Cure, Frederick A. Stokes, 1919, Archive.org, accessed 14 February 2014.

- "George Robey", Hull Daily Mail, 18 September 1942, p. 1.

- Cotes, p. 170.

- Cotes, p. 87.

- Wilson, p. 111.

- Cotes, p. 74.

- "Stoll Picture Productions", British Film Institute, accessed 5 February 2014.

- Wilson, p. 112.

- George Robey's Day Off, British Film Institute, accessed 1 February 2014.

- Wilson, p. 151.

- "Variety Theatre", Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed 25 December 2013.

- Cotes, p. 71.

- Cotes, pp. 71–72.

- Cotes, p. 88.

- "George Robey and the Printers", The Devon and Exeter Gazette, 27 August 1920, p. 15.

- "The Prince of Wales and the 1937 Coronation" Archived 7 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Scouting Milestones, accessed 27 January 2014.

- Quoted in Cotes, p. 66.

- Cotes, p. 66.

- Wilson, p. 114.

- Cotes, p. 89.

- "One Arabian Night", British Film Institute, accessed 2 February 2014.

- "Harlequinade", British Film Institute, accessed 2 February 2014.

- "Chaplin-In-Context", British Film Institute, p. 2, accessed 4 January 2014.

- Cotes, p. 90.

- Cotes, p. 91.

- Wilson, p. 122.

- Wilson, pp. 122–123.

- Wilson, p. 123.

- Cotes, p. 92.

- Wilson, p. 121.

- Morley, Sheridan. "Littler, Prince Frank", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed 10 May 2014. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Cotes, p. 193.

- Marry Me, British Film Institute, accessed 23 February 2014.

- Wilson, p. 152.

- Wilson, pp. 151–152.

- Wilson, p. 155.

- Cotes, p. 119.

- "Sir George Robey", Britannica, accessed 31 January 2014.

- Cotes, p. 94.

- Cotes, p. 95.

- Wilson, p. 129.

- Wilson, pp. 129–130.

- Quoted in Wilson, p. 130.

- Cotes, p. 199.

- Sutton, Graham. "The Bookman's Table": Looking Back on Life, by George Robey", The Bookman, p. 132, No. 506, Vol. 85, November 1933, accessed 7 May 2014.

- Wilson, pp. 137–138.

- Cotes, p. 116.

- Wilson, p. 137.

- "Chu Chin Chow (1934): A Robust Operetta". The New York Times, 22 September 1934, accessed 2 August 2010

- Cotes, p. 118.

- Quoted in Wilson, p. 135.

- Quoted in Wilson, p. 136.

- Wilson, p. 135.

- "George Robey Would Be a Great Falstaff—If Only He Could Gag!", The Daily Express, 1 March 1935, p. 1.

- "Henry IV, Part I", The Observer, 3 March 1935, p. 17.

- "It Takes Three Years to Equal This Robey", Daily Mirror, 1 March 1935, p. 1.

- Cotes, p. 117.

- Cotes, p. 123.

- Quoted in Cotes, p. 120.

- Wilson, p. 158.

- Anonymous reporter from Variety Life, quoted in Wilson, pp. 158–159.

- The Times, 20 November 1925, p. 20.

- Wilson, p. 159.

- A Girl Must Live, British Film Institute, accessed 11 February 2014.

- Quote taken from Kinematograph Weekly; Wilson, p. 157.

- Quoted in Wilson, p. 157.

- Cotes, p. 114.

- Quoted in Cotes, p. 114.

- Wilson, p. 197.

- "George Robey Married", Derby Daily Telegraph, 28 November 1938, p. 1.

- "Noted Comedian Weds", Montreal Gazette, 1 December 1938, p. 7.

- "George Robey: More Restful Night But Still In Pain", Derby Daily Telegraph, 4 January 1939, p. 1.

- Cotes, pp. 159–160.

- Cotes, pp. 162–163.

- Cotes, p. 163.

- Cotes, pp. 163–164.

- Salute John Citizen, British Film Institute, accessed 18 March 2014.

- "Salute John Citizen", The Australian Women's Weekly, 29 January 1944, p. 19.

- "George Robey", British Film Institute, accessed 18 March 2014.

- "Music Hall and Variety", Britannica, accessed 18 March 2014.

- Cotes, p. 164.

- Crowther, Bosley. "The Screen: Henry V (1944)", The New York Times, 18 June 1946, accessed 24 March 2014.

- "Vive Paree", Burnley Express, 18 November 1944, p. 1.

- The Trojan Brothers, British Film Institute, accessed 24 February 2014.

- Waltz Time, British Film Institute, accessed 24 March 2014.

- Wilson, p. 220.

- Fazan, p. 22.

- Wilson, p. 221.

- Wilson, pp. 221–222.

- Wilson, p. 222.

- "Desert Island Discs: George Robey", BBC, accessed 17 March 2014.

- Fisher, p. 117.

- Wilson, p. 223.

- Quoted in Wilson, p. 224.

- Quoted in Wilson, p. 225.

- Wilson, p. 226.

- Wilson, p. 227.

- Cotes, p. 194.

- "George Robey Knighted", The Advocate, 18 February 1954, p. 1, accessed 6 December 2013.

- Wilson, p. 238.

- Wilson, p. 239.

- Wilson, p. 240.

- "Prime Minister of Mirth: A Comic Genius – Death of Sir George Robey", The Glasgow Herald, 30 November 1954, p. 8.

- "Music Hall and Variety Artistes Burial Places" (Arthur Lloyd theatre history), accessed 14 February 2014.

- "Names on the buses – 712 George Robey", Brighton & Hove Bus Company, accessed 10 February 2014.

- Quoted in Wilson, p. 240.

- Wilson, Cecil. Quoted in Wilson, p. 240.

- "Sidelight: Compton Mackenzie", The Spectator (archive), 10 December 1954, p. 18.

- Cotes, p. 3.

- "Sir George Robey: The Prime Minister of Mirth", it's-behind-you.com, accessed 8 December 2013.

- Cotes, p. 7.

- Cotes, p. 167.

- Cotes, p. 4.

- Cotes, p. 179.

- Quoted in Wilson, p. 242.

Sources

- Baker, Richard Anthony (2005). British Music Hall: An Illustrated History. London: Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7509-3685-1.

- Cotes, Peter (1972). George Robey: The Darling of the Halls. London: Cassell & Company Ltd. ISBN 978-0-304-93844-5.

- Fazan, Eleanor (2013). Fiz: And Some Theatre Giants. Victoria, British Columbia: Friesen Press. ISBN 978-1-4602-0102-2.

- Fisher, John (2013). Funny Way to Be a Hero. London: Preface Press. ISBN 978-1-84809-313-3.

- Horrall, Andrew (2001). Popular Culture in London c. 1890–1918: The Transformation of Entertainment. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5782-3.

- Maloney, John (2003). Scotland and the Music Hall 1850–1914. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6147-9.

- Parrill, Sue and William B. Robison (2013). The Tudors on Film and Television. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-0031-4.

- Stone, Harry (2009). The Century of Musical Comedy and Revue. Indiana: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4343-8865-0.

- St. Pierre, Paul Matthew (2009). Music Hall Mimesis in British Film, 1895–1960: On the Halls on the Screen. Vancouver: Associated University Presse. ISBN 978-0-8386-4191-0.

- Wilson, Albert Edward (1956). Prime Minister of Mirth. The biography of Sir George Robey, C.B.E. With plates, including portraits. Michigan: Odham Press. OCLC 1731822.

External links

- George Robey at IMDb

- Brief biography at The English Music Hall

- Robey at Its Behind You

- Ye Olde Tree and Crown

- Robey at Pathe News

- Signed photo of Robey in character

- Eight digitally restored recordings of George Robey