Halo Array

The Halo Array is a group of fictional megastructures and superweapons in the Halo science fiction franchise, consisting of ringworlds known as Halos built by structures known as the Ark. They are referred to as "Installations" by their artificial intelligence caretakers, and were created by an ancient race known as the Forerunners. The series' alien antagonists, the Covenant, refer to the Halos as the "Sacred Rings", believing them to form part of a greater religious prophecy known as "The Great Journey". In the games' stories, the Forerunners built the Halo Array to contain and study the Flood, an infectious alien parasite. The rings act together as a weapon of last resort; when fired, they kill all sentient life in the galaxy capable of falling prey to the Flood, thereby starving the parasite of its food. The battle to prevent their activation forms the crux of the plot progression for the first Halo trilogy of games.

Each Halo features its own wildlife and weather. The constructs resemble Iain M. Banks' Orbital concept in shape and design.[1][2] The structure on which Halo: Combat Evolved takes place was initially intended to be a hollowed-out planet, but was changed to its ring design later in development; a staff member provided "Halo" as the name for both the ring and the video game after names such as Red Shift were suggested.

Overview

Design and development

The term "megastructure" refers to artificial structures where one of three dimensions is 100 kilometers (62 mi) or larger. The first use of a ring-shaped megastructure in fiction was Larry Niven's novel Ringworld (1970). Niven described his design as an intermediate step between Dyson spheres and planets – a ring with a radius of more than 93,000,000 miles (150,000,000 km) and a width of 1,000,000 miles (1,600,000 km); these dimensions far exceed those of the ringworlds found in the Halo series, which have radii of 6,213.712 miles (10,000.000 km)[3] The Halos are closer in proportion to a Bishop Ring, an actual proposed space habitat first explained by Forrest Bishop, though the proportions of the Halos do not exactly match up with Bishop's idea or more accurately the bigger Orbital. As seen in the games, Halo installations feature a metallic exterior but an inner surface filled with an atmosphere, water, plant life, and animal life.[4] What appear to be docking ports and windows dot the exterior surface, suggesting that a fraction of the ring structure itself is hollow and used for maintenance, living, and power generation.[5]

Before the title of the game that would become Halo: Combat Evolved was announced, while development was in its early stages, the megastructure on which the game took place was a massive, hollowed-out planet called "Solipsis". As ideas evolved, the planet became a Dyson Sphere, and then a Dyson Ring.[6] Some Bungie staffers felt the change to a ringworld was "ripping off Larry Niven", according to Bungie artist Paul Russel.[7] Bungie employee Frank O'Connor wrote in a post on Bungie that "the specific accusation that we swiped the idea of a ring-shaped planet wholesale is not accurate", explaining that Bungie used a ringworld because "it's cool and therefore the type of thing a Forerunner civilization would build."[8] The immense scale of the Dyson megastructures was shrunk for the Halos, as artist Mark Goldsworthy noted that they wanted players to be able to see the ring stretching into the sky and behold the scale of the ringworlds.[9]

At the time, the game was known as Blam!, but Bungie had always expected to replace the working title with something better. Blam! was used after studio co-founder Jason Jones could not bring himself to tell his mother their next project was dubbed Monkey Nuts.[10] Titles such as The Crystal Palace, Hard Vacuum, Star Maker, Star Shield, and The Santa Machine were suggested.[6] Russel suggested calling it Project: Halo because of the ring. Despite concerns that the title seemed too religious or lacked action, the name stuck.[11] In turn, "Halo" became the ring's name as well.[7][12]

Combat Evolved's Halo was intended to be populated with large animal life,[13] collectively known as Fauna. The Fauna included "pseudo-dinosaurs" and mammals,[14] as well as a Chocobo-like creature—the "Blind Wolf"—that players could ride.[15] The animals were removed for technical and conceptual reasons; there were difficulties in getting herd and behavior action to work, and under pressure to complete the game's more central aspects, the animals were dropped. Bungie also felt that the desolate ring heightened the sense of Halo's mystery, and made the appearance of the parasitic Flood more terrifying and unexpected.[14]

Scientific analysis

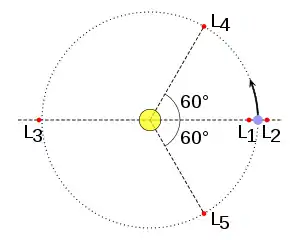

Physicist Kevin Grazier posited in a 2006 essay the composition and problems associated with a Halo installation. The complete Halos seen in Halo: Combat Evolved and Halo 2 orbit gas giants similar to Jupiter, though much larger; the bodies exhibit characteristics of both a jovian planet and a small star.[16] In each system, there are five points where a body of negligible mass would remain stationary to the two much larger bodies in the system, the gas giant and its moon. These areas, known as Lagrange points, are classified by stability; while bodies at 60° angles to the gas giant would remain in the same location relative to the other objects in the system, the other three Lagrange points are meta-stable, having the tendency to be unstable in one direction. As the Halos are located at point L1, the installations must actively correct their orbits.[17] The apparent gravity of the Halo installations is close to Earth normal. A Halo would have to spin with a tangential speed of 7 kilometers (4.3 mi) per second to match Earth's gravity, translating to 19.25 rotations in a day.[18]

Aside from their unstable positions, Halos would have to contend with thousands of meteor and micrometeor impacts which would destabilize or destroy the ring; there is no evidence in the games that the installations project an energy shield to prevent this occurrence.[16] Because of the magnetic environment around the gas giant, a Halo would also be exposed to high levels of radiation.[19] Earth is protected from such radiation by charged particles created by the planet's magnetic field. Grazier posits that huge conductive cables could run the circumference of a Halo; when an electric current was run through these cables, a protective magnetic environment could be created to sustain life.[20]

In the games, spectroscopic analysis of the ring's composition proved "inconclusive", implying that the Halos are constructed of an unknown material (unobtainium). Were a Halo to be constructed using conventional materials a light steel alloy would be most feasible. Assuming that the ring structure is 50% empty space, a 5000 km ring composed of steel alloy at an average density of 7.7 grams (0.27 oz) per 1 cubic centimeter (0.061 cu in) would result in a total mass of 1.7x1017 kg.[5] The amount of material required to build such a ring would be akin to the total material available in the asteroid belt.[21]

Installations

The Ark

The Ark, also referred to as Installation 00 and the Lesser Ark, is located outside the Milky Way galaxy and serves as the construction and control station for the Halo weapon system. During Halo 3, the alien Covenant, intent on activating the rings in a mistaken belief they will attain godhood rather than eliminate sentient life, travel to the Ark via a portal on Earth. The Flood intelligence Gravemind, having hijacked the Covenant city-ship High Charity, crash-lands on the installation. The firing of the rings is halted by Master Chief and the Arbiter. In order to end the threat of the Flood, Master Chief decides to activate a Halo ring under construction in the Ark, destroying the local Flood while sparing the galaxy. The firing tears apart the incomplete Halo and severely damages the Ark as Master Chief, Cortana, and the Arbiter try to escape through the portal. The location makes later appearances in Halo: Hunters in the Dark, in which the installation's artificial intelligence Tragic Solitude attempts to harvest Earth for materials to repair the installation, and Halo Wars 2, where humans and a faction of aliens known as the Banished fight for control of the Ark.

Installation 03

Installation 03, also referred to as Gamma Halo, appears in Halo 4. It is monitored by 049 Abject Testament and is located in the Khaphrae system, orbiting a damaged planet. Whilst no gameplay takes place on the installation, an extremely dense asteroid field surrounding the installation is the site of the UNSC scientific research base Ivanoff. It is here that UNSC scientists are conducting experiments on the Forerunner artifact called the Composer, which has the ability to convert biological forms, specifically humans, into AIs. After the game's antagonist, the Didact, activates the device, the UNSC base is left uninhabited. Halo: Escalation, a series of comics which follows many events after Halo 4, establishes that 049 Abject Testament has long disappeared from the ring, leading a monitor to arrive at the Installation, just to be ambushed by a still-living Didact, using the Installation to use the Composer. At the end of the comics, Abject Testament takes the installation to an unknown location for repairs.

Installation 04

Installation 04, also referred to as Alpha Halo, appears in Halo: Combat Evolved. The majority of gameplay takes place in areas on this installation, and its exploration drives the story.[22] The ring is located in the Soell system, dominated by a gas giant known as Threshold, and is managed by an artificial intelligence known as 343 Guilty Spark.[23] Installation 04 orbits Threshold's only satellite, an extremely large moon known as Basis.[16] A group of humans aboard the ship Pillar of Autumn crash-land on the ring after being pursued by the alien Covenant.[24] The ring holds religious significance to the Covenant, while the humans believe it is a weapon that could turn the tide of the war against the Covenant in their favor.[22] In reality, the ring is a containment facility for a virulent parasite called the Flood, which is accidentally released by the Covenant and threatens to infest the galaxy. The human soldier Master Chief eventually detonates the Pillar of Autumn's reactors in order to destabilize the ring and cause it to break up, preventing the spread of the Flood and the activation of the Halo network, which would kill all sentient life as a fail-safe to starve the Flood.[25] Two replacement installations for Installation 04, designated Installation 08 and 09, are seen in Halo 3 and Halo Wars 2, respectively. It is later seen in the production Halo Nightfall

Installation 05

During the events of Halo 2, the Covenant and humans discover a second ringworld, Installation 05, or Delta Halo. It is monitored by 2401 Penitent Tangent, who completely ignores Flood warnings and is captured by the Gravemind. The Covenant leadership wants to activate the installation, believing it is the key to their salvation. At the same time, the Flood lay siege to the Covenant's city-ship, High Charity. After 343 Guilty Spark reveals Halo's true purpose to the Arbiter, a Covenant holy warrior, and warns him of the danger that the Halos truly represent, a group of humans and Covenant Elites prevent the firing of the ring.[26] The unexpected shutdown activates a fail-safe protocol, priming the remaining Halo installations for remote activation from a location known as The Ark.

In Halo 4, it is revealed that the UNSC has created an oversight base on Installation 05 (or around it), as they did with Installation 03. It is mentioned in the novel Halo: Hunters in the Dark that the Elites "scorched the surface to char and ash" to contain the remaining Flood on the ring.

Installation 07

Installation 07, also referred to as Zeta Halo, is the oldest and most mysterious of the Halo rings. Unlike the other installations, Installation 07 was part of an older, larger array. It was originally 30,000 kilometers wide, compared to its current 10,000 kilometer diameter. First appearing in Halo: Cryptum, Installation 07 falls under the control of the rogue Forerunner AI Mendicant Bias, who used it to attack his former Forerunner masters during the war between the Forerunner and Flood. In Halo: Hunters in the Dark, taking place in 2555, the UNSC discover and establish a base on the ring. It is the main setting of Halo Infinite.

See also

Notes

- Cuddy, Luke (2011-06-07). Halo and Philosophy: Intellect Evolved. Open Court. ISBN 978-0812697186.

[...] Banks put out the Culture series of books, which envisions a slightly smaller structure called an "orbital" -- probably closer to the Halo structures [...]

- Sones, Benjamin E. (2000-07-14). "Bungie dreams of rings and things, part 2". Computer Games Online. Archived from the original on 2005-04-08. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

we don't want people to think this is the game of Niven's Ringworld, simply because it takes place on a ring-shaped artificial world... you'd be surprised how often people assume this. ... structurally it's more similar to the 'orbitals' in Iain M. Banks' Culture novels.

- Grazier (2006), 39–40.

- Hiatt (1999), 94–96.

- Grazier (2006), 41.

- McLaughlin (2007), 1.

- Jarrard, et al (2008).

- Perry (2006), 6.

- Robinson (2011), 40.

- Trautmann (2004), ix.

- Trautmann (2004), 73.

- Toyama (2001), 61.

- Preston (2000), 19.

- Bungie.

- Lehto, et al (2002).

- Grazier (2006), 44–45.

- Grazier (2006), 46.

- Grazier (2006), 49.

- Grazier (2006), 47.

- Grazier (2006), 48.

- Grazier (2006), 42.

- Trautmann (2004), 77.

- Grazier (2006), 43.

- Trautmann (2004), viii.

- Barrat (2007), 2.

- Barrat (2007), 3.

References

- Robinson, Martin (2011). Halo: The Great Journey – The Art of Building Worlds. Titan Books. ISBN 978-0857685629.

- Barratt, Charlie (2007-09-22). "Halo: The Story So Far". GamesRadar. pp. 1–4. Archived from the original on 2013-01-24. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- Bungie (2006-02-10). "One Million Years B.X." Bungie. Archived from the original on 2006-02-10. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- Gillen, Kieron (July 2000). "Halo, Beautiful". PC Gamer UK: 45.

- Grazier, Kevin (2006). "Halo Science 101". In Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). Halo Effect: The Unauthorized Look at the Most Successful Video Game of All Time. Dallas, Texas: BenBella Books. ISBN 1-933771-11-9.

- Hiatt, Jesse (November 1999). "Halo; the closest thing to the real thing". Computer Gaming World: 94–96.

- Jarrard, Brian; Smith, Luke (2008-08-21). "Bungie Podcast: 08/21/08; With Paul Russel and Jerome Simpson". Bungie. Archived from the original on 2008-03-31. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- Lehto, Marcus; Martin O'Donnell; Robert McClees; Paul Russell (2002). Evolution of Halo. Electronic Entertainment Expo: Bungie. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- McLaughlin, Rus (2007-09-20). "IGN Presents The History of Halo". IGN. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- McLees, Robert; O'Connor, Frank; Staten, Joseph (2006-08-01). "HBO interview with Joseph Staten". Halo.Bungie.Org. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- Perry, Douglass C (2006-05-17). "The Influence of Literature and Myth in Videogames". IGN. pp. 1–6. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- Preston, Jim (August 2000). "Scoop!; Halo". PC Gamer: 19.

- Toyama, Kevin (May 2001). "Cover Story: Holy Halo". Next Generation Magazine: 61.

- Trautmann, Eric (2004). The Art of Halo. New York: Del Ray Publishing. ISBN 0-345-47586-0.