Hawala

Hawala or hewala (Arabic: حِوالة ḥawāla, meaning transfer or sometimes trust), also known as havaleh in Persian,[1] and xawala or xawilaad[2] in Somali, is a popular and informal value transfer system based not on the movement of cash, or on telegraph or computer network wire transfers between banks, but instead on the performance and honour of a huge network of money brokers (known as hawaladars). While hawaladars are spread throughout the world, they are primarily located in the Middle East, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and the Indian subcontinent, operating outside of, or parallel to, traditional banking, financial channels, and remittance systems. Hawala follows Islamic traditions but its use is not limited to Muslims.[3]

| Financial market participants |

|---|

Origins

The hawala system originated in India.[4] It has existed since the 8th century between Indian, Arabic, and Muslim traders who operated alongside the Silk Road and beyond, as a protection against theft. It is believed to have arisen in the financing of long-distance trade around the emerging capital trade centers in the early medieval period. In South Asia, it appears to have developed into a fully-fledged money market instrument, which was only gradually replaced by the instruments of the formal banking system in the first half of the 20th century.

"Hawala" itself influenced the development of the agency in common law and in civil laws, such as the aval in French law and the avallo in Italian law. The words aval and avallo were themselves derived from hawala.[5] The transfer of debt, which was "not permissible under Roman law but became widely practiced in medieval Europe, especially in commercial transactions", was due to the large extent of the "trade conducted by the Italian cities with the Muslim world in the Middle Ages". The agency was also "an institution unknown to Roman law" as no "individual could conclude a binding contract on behalf of another as his agent". In Roman law, the "contractor himself was considered the party to the contract and it took a second contract between the person who acted on behalf of a principal and the latter in order to transfer the rights and the obligations deriving from the contract to him". On the other hand, Islamic law and the later common law "had no difficulty in accepting agency as one of its institutions in the field of contracts and of obligations in general".[6]

Today, hawala is probably used mostly for migrant workers' remittances to their countries of origin.

How hawala works

In the most basic variant of the hawala system, money is transferred via a network of hawala brokers, or hawaladars. It is the transfer of money without actually moving it. In fact, a successful definition of the hawala system that is used is "money transfer without money movement". According to author Sam Vaknin, while there are large hawaladar operators with networks of middlemen in cities across many countries, most hawaladars are small businesses who work at hawala as a sideline or moonlighting operation.[3]

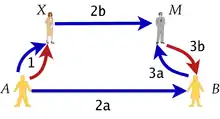

The figure shows how hawala works: (1) a customer (A, left-hand side) approaches a hawala broker (X) in one city and gives a sum of money (red arrow) that is to be transferred to a recipient (B, right-hand side) in another, usually foreign, city. Along with the money, he usually specifies something like a password that will lead to the money being paid out (blue arrows). (2b) The hawala broker X calls another hawala broker M in the recipient's city, and informs M about the agreed password, or gives other disposition of the funds. Then, the intended recipient (B), who also has been informed by A about the password (2a), now approaches M and tells him the agreed password (3a). If the password is correct, then M releases the transferred sum to B (3b), usually minus a small commission. X now basically owes M the money that M had paid out to B; thus M has to trust X's promise to settle the debt at a later date.

The unique feature of the system is that no promissory instruments are exchanged between the hawala brokers; the transaction takes place entirely on the honour system. As the system does not depend on the legal enforceability of claims, it can operate even in the absence of a legal and juridical environment. Trust and extensive use of connections are the components that distinguish it from other remittance systems. Hawaladar networks are often based on membership in the same family, village, clan, or ethnic group, and cheating is punished by effective excommunication and "loss of honour"—leading to severe economic hardship.[3]

Informal records are produced of individual transactions, and a running tally of the amount owed by one broker to another is kept. Settlements of debts between hawala brokers can take a variety of forms (such as goods, services, properties, transfers of employees, etc.), and need not take the form of direct cash transactions.

In addition to commissions, hawala brokers often earn their profits through bypassing official exchange rates. Generally, the funds enter the system in the source country's currency and leave the system in the recipient country's currency. As settlements often take place without any foreign exchange transactions, they can be made at other than official exchange rates.

Hawala is attractive to customers because it provides a fast and convenient transfer of funds, usually with a far lower commission than that charged by banks. Its advantages are most pronounced when the receiving country applies unprofitable exchange rate regulations or when the banking system in the receiving country is less complex (e.g., due to differences in legal environment in places such as Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia). Moreover, in some parts of the world it is the only option for legitimate fund transfers, and has even been used by aid organizations in areas where it is the best-functioning institution.[7]

Regional variants

Dubai has been prominent for decades as a welcoming hub for hawala transactions worldwide.[8]

Hundis

The hundi is a financial instrument that developed on the Indian sub-continent for use in trade and credit transactions. Hundis are used as a form of remittance instrument to transfer money from place to place, as a form of credit instrument or IOU to borrow money and as a bill of exchange in trade transactions. The Reserve Bank of India describes the Hundi as "an unconditional order in writing made by a person directing another to pay a certain sum of money to a person named in the order."[9]

Angadia

The word angadia means courier in Hindi, but also designates those who act as hawaladars within India. These people mostly act as a parallel banking system for businessmen. They charge a commission of around 0.2–0.5% per transaction from transferring money from one city to another.

Horn of Africa

According to the CIA, with the dissolution of Somalia's formal banking system, many informal money transfer operators arose to fill the void. It estimates that such hawaladars, xawilaad or xawala brokers [2][10] are now responsible for the transfer of up to $1.6 billion per year in remittances to the country,[11] most coming from working Somalis outside Somalia.[12] Such funds have in turn had a stimulating effect on local business activity.[11][12]

West Africa

The 2012 Tuareg rebellion left Northern Mali without an official money transfer service for months. The coping mechanisms that appeared were patterned on the hawala system.[13]

Post-9/11 money laundering crackdowns

Some government officials assert that hawala can be used to facilitate money laundering, avoid taxation, and move wealth anonymously. As a result, it is illegal in some U.S. states, India, Pakistan,[14] and some other countries.

After the September 11 terrorist attacks, the American government suspected that some hawala brokers may have helped terrorist organizations transfer money to fund their activities, and the 9/11 Commission Report stated that "Al Qaeda frequently moved the money it raised by hawala".[15] As a result of intense pressure from the U.S. authorities to introduce systematic anti-money laundering initiatives on a global scale, a number of hawala networks were closed down and a number of hawaladars were successfully prosecuted for money laundering. However, there is little evidence that these actions brought the authorities any closer to identifying and arresting a significant number of terrorists or drug smugglers.[16] Experts emphasized that the overwhelming majority of those who used these informal networks were doing so for legitimate purposes, and simply chose to use a transaction medium other than state-supported banking systems.[7] Today, the hawala system in Afghanistan is instrumental in providing financial services for the delivery of emergency relief and humanitarian and developmental aid for the majority of international and domestic NGOs, donor organizations, and development aid agencies.[17]

In November 2001, the Bush administration froze the assets of Al-Barakat, a Somali remittance hawala company used primarily by a large number of Somali immigrants. Many of its agents in several countries were initially arrested, though later freed after no concrete evidence against them was found. In August 2006 the last Al-Barakat representatives were taken off the U.S. terror list, though some assets remain frozen.[18] The mass media has speculated that pirates from Somalia use the hawala system to move funds internationally, for example into neighboring Kenya, where these transactions are neither taxed nor recorded.[19]

In January 2010, the Kabul office of New Ansari Exchange, Afghanistan's largest hawala money transfer business, was closed following a raid by the Sensitive Investigative Unit, the country's national anti-political corruption unit, allegedly because this company was involved in laundering profits from the illicit opium trade and the moving of cash earned by government allied warlords through extortion and drug trafficking. Thousands of records were seized, from which links were found between money transfers by this company and political and business figures and NGOs in the country, including relatives of President Hamid Karzai.[20] In August 2010, Karzai took control of the task force that staged the raid, and the US-advised anti-corruption group, the Major Crimes Task Force. He ordered a commission to review scores of past and current anti-corruption inquests.[21]

Between October 2010 and June 2012, the U.S. government charged four Somali defendants with laundering $10,900 for al-Shabaab using hawalas. The defendants were Basaaly Saeed Moalin, Mohamed Mohamed Mohamud, Issa Doreh, and Ahmed Nasir Taalil Mohamud. The indictment relied upon illegally collected metadata under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. The convictions were upheld by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.[22]

See also

- Economy related

- Global ranking of remittance by nations

- Remittances to India

- Hundi

- Informal value transfer system

- FATF

- Related contemporary issues

References

- "Subscribe to read". Cite uses generic title (help)

- Thompson, Edwina (September 2013). Safer corridors rapid assessment — Somalia and UK banking (PDF). HM Government. p. 5. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- Vaknin, Sam (June 2005). "Hawala, or the Bank that Never Was". samvak.tripod.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- (PDF) https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/terrorist-illicit-finance/Documents/FinCEN-Hawala-rpt.pdf. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Badr, Gamal Moursi (Spring 1978). "Islamic Law: Its Relation to Other Legal Systems". American Journal of Comparative Law. 26 (2 [Proceedings of an International Conference on Comparative Law, Salt Lake City, Utah, February 24–25, 1977]): 187–98. doi:10.2307/839667. JSTOR 839667.

- Badr, Gamal Moursi (Spring 1978). "Islamic Law: Its Relation to Other Legal Systems". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 26 (2 [Proceedings of an International Conference on Comparative Law, Salt Lake City, Utah, February 24–25, 1977]): 187–98 [196–8]. doi:10.2307/839667. JSTOR 839667.

- Passas, Nikos (2006). "Demystifying Hawala: A Look into its Social Organization and Mechanics". Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention. 7 (suppl 1): 46–62. doi:10.1080/14043850601029083. S2CID 145753289.

- "Hawala" (PDF). www.treasury.gov. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network with Interpol/FOPAC. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- Hundies, Reserve Bank of India, 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013. Archived here.

- Monbiot, George (2016). How did we get into this mess? (First ed.). Verso. pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-1-78478-362-4.

- "Somalia", The World factbook, US: Central Intelligence Agency.

- "Economy & Finance: Hawaladars", CBS, Somal banca, archived from the original on 2009-01-24, retrieved 2018-12-05.

- "Malians Shelter to Black Market to Transfer Cash". Voice of America. August 29, 2012. Archived from the original on September 1, 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- Jost, Patrick M.; Sandhu, Harjit Singh. "The Hawala Alternative Remittance System and its Role in Money Laundering" (PDF). Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2016. Retrieved September 5, 2016..

- Desrosiers, David A. "Al Qaeda Aims at the American Homeland - A Money Trail?". 911.gnu-designs.com.

- Passas, Nikos (November 2006). "Fighting terror with error: the counter-productive regulation of informal value transfers" (PDF). Crime, Law and Social Change. 45 (4–5): 315–36. doi:10.1007/s10611-006-9041-5. S2CID 153709254. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- Maimbo, Samuel Munzele (August 1, 2003), The money exchange dealers of Kabul – a study of the Hawala system in Afghanistan, The World Bank, p. 1, archived from the original on March 19, 2012, retrieved September 5, 2016.

- "US ends Somali banking blacklist". BBC News. UK. August 28, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- "Somali Pirates Take The Money And Run, To Kenya". NPR. 2010-05-05. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- "Afghan hawala ring tied to Karzai kinh". The Times of India. August 13, 2010. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- Rosenberg, Matthew (June 25, 2010). "Corruption Suspected in Airlift of Billions in Cash From Kabul". The Wall Street Journal. New York, NY, US. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- UNITED STATES V. MOALIN, F.3d (D.C. Cir. September 2, 2020).

Further reading

- Ballard, Roger, Hawala (collection of academic papers), UK: Casas, archived from the original on 2011-05-19, retrieved 2008-12-15, exploring the operation of contemporary hawala networks, and the role they play in the transmission of migrant workers' remittances from Europe to South Asia.

- Bowers, Charles (2009), "The international legal/political consequences of hawala and money laundering", Denver Journal of International Law and Policy (academic paper), archived from the original on 2010-08-29, retrieved 2009-03-17.

- Thompson, Dr. Edwina A, The Nexus of Drug Trafficking and Hawala in Afghanistan (PDF), The World Bank and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

- Wilson, John F (October 2003), Informal Funds Transfer Systems: An Analysis of the Hawala System (PDF) (occasional paper), et al., International Monetary Fund, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-09-23, retrieved 2011-01-05.

- "Fears over US hawala crackdown". BBC News. London. February 4, 2004.

- "Hawala" (PDF), Key issues, US: Department of The Treasury, Treasury Department Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN).

- Hawala fraud, UK: BBC News, April 2007.

- Hawala, everything2.com.