Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age (Arabic: العصر الذهبي للإسلام, romanized: al-'asr al-dhahabi lil-islam), was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century.[1][2][3] This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (786 to 809) with the inauguration of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, the world's largest city by then, where Islamic scholars and polymaths from various parts of the world with different cultural backgrounds were mandated to gather and translate all of the world's classical knowledge into Arabic and Persian.[4][5]

| 8th century – 14th century | |

Clockwise from top: Al-Zahrawi, Abbas ibn Firnas, Al-Biruni, Avicenna, Averroes, Ibn al-Nafis, ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, Alhazen, Ibn Khaldun | |

| Preceded by | Rashidun Caliphate |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Timurid Renaissance, Age of the Islamic Gunpowders |

| Monarch(s) | Umayyad, Abbasid, Samanid, Fatimid, Ayyubid, Mamluk |

| Leader(s) | |

The period is traditionally said to have ended with the collapse of the Abbasid caliphate due to Mongol invasions and the Siege of Baghdad in 1258.[6] A few scholars date the end of the golden age around 1350 linking with the Timurid Renaissance,[7][8] while several modern historians and scholars place the end of the Islamic Golden Age as late as the end of 15th to 16th centuries meeting with the Age of the Islamic Gunpowders.[1][2][3] (The medieval period of Islam is very similar if not the same, with one source defining it as 900–1300 CE.)[9]

History of the concepts

The metaphor of a golden age began to be applied in 19th-century literature about Islamic history, in the context of the western aesthetic fashion known as Orientalism. The author of a Handbook for Travelers in Syria and Palestine in 1868 observed that the most beautiful mosques of Damascus were "like Mohammedanism itself, now rapidly decaying" and relics of "the golden age of Islam".[10]

There is no unambiguous definition of the term, and depending on whether it is used with a focus on cultural or on military achievement, it may be taken to refer to rather disparate time spans. Thus, one 19th century author would have it extend to the duration of the caliphate, or to "six and a half centuries",[11] while another would have it end after only a few decades of Rashidun conquests, with the death of Umar and the First Fitna.[12]

During the early 20th century, the term was used only occasionally and often referred to as the early military successes of the Rashidun caliphs. It was only in the second half of the 20th century that the term came to be used with any frequency, now mostly referring to the cultural flourishing of science and mathematics under the caliphates during the 9th to 11th centuries (between the establishment of organised scholarship in the House of Wisdom and the beginning of the crusades),[13] but often extended to include part of the late 8th or the 12th to early 13th centuries.[14] Definitions may still vary considerably. Equating the end of the golden age with the end of the caliphates is a convenient cut-off point based on a historical landmark, but it can be argued that Islamic culture had entered a gradual decline much earlier; thus, Khan (2003) identifies the proper golden age as being the two centuries between 750 and 950, arguing that the beginning loss of territories under Harun al-Rashid worsened after the death of al-Ma'mun in 833, and that the crusades in the 12th century resulted in a weakening of the Islamic empire from which it never recovered.[15]

Causes

Religious influence

The various Quranic injunctions and Hadith (or actions of Muhammad), which place values on education and emphasize the importance of acquiring knowledge, played a vital role in influencing the Muslims of this age in their search for knowledge and the development of the body of science.[16][17][18]

Government sponsorship

The Islamic Empire heavily patronized scholars. The money spent on the Translation Movement for some translations is estimated to be equivalent to about twice the annual research budget of the United Kingdom's Medical Research Council.[19] The best scholars and notable translators, such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq, had salaries that are estimated to be the equivalent of professional athletes today.[19] The House of Wisdom was a library established in Abbasid-era Baghdad, Iraq by Caliph al-Mansur.[20]

Diverse contributions

During this period, the Muslims showed a strong interest in assimilating the scientific knowledge of the civilizations that had been conquered. Many classic works of antiquity that might otherwise have been lost were translated from Greek, Persian, Indian, Chinese, Egyptian, and Phoenician civilizations into Arabic and Persian, and later in turn translated into Turkish, Hebrew, and Latin.[5]

Christians, especially the adherents of the Church of the East (Nestorians), contributed to Islamic civilization during the reign of the Ummayads and the Abbasids by translating works of Greek philosophers and ancient science to Syriac and afterwards to Arabic.[21][22] They also excelled in many fields, in particular philosophy, science (such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq,[23][24] Yusuf Al-Khuri,[25] Al Himsi,[26] Qusta ibn Luqa,[27] Masawaiyh,[28][29] Patriarch Eutychius,[30] and Jabril ibn Bukhtishu[31]) and theology. For a long period of time the personal physicians of the Abbasid Caliphs were often Assyrian Christians.[32][33] Among the most prominent Christian families to serve as physicians to the caliphs were the Bukhtishu dynasty.[34][35]

Throughout the 4th to 7th centuries, Christian scholarly work in the Greek and Syriac languages was either newly translated or had been preserved since the Hellenistic period. Among the prominent centers of learning and transmission of classical wisdom were Christian colleges such as the School of Nisibis[36] and the School of Edessa,[37] the pagan University of Harran[38][39] and the renowned hospital and medical academy of Jundishapur, which was the intellectual, theological and scientific center of the Church of the East.[40][41][42] The House of Wisdom was founded in Baghdad in 825, modelled after the Academy of Gondishapur. It was led by Christian physician Hunayn ibn Ishaq, with the support of Byzantine medicine. Many of the most important philosophical and scientific works of the ancient world were translated, including the work of Galen, Hippocrates, Plato, Aristotle, Ptolemy and Archimedes. Many scholars of the House of Wisdom were of Christian background.[43]

Among the various countries and cultures conquered through successive Islamic conquests, a remarkable number of scientists originated from Persia, who contributed immensely to the scientific flourishing of the Islamic Golden Age. According to Bernard Lewis: "Culturally, politically, and most remarkable of all even religiously, the Persian contribution to this new Islamic civilization is of immense importance. The work of Iranians can be seen in every field of cultural endeavor, including Arabic poetry, to which poets of Iranian origin composing their poems in Arabic made a very significant contribution."[44] Science, medicine, philosophy and technology in the newly Islamized Iranian society was influenced by and based on the scientific model of the major pre-Islamic Iranian universities in the Sassanian Empire. During this period hundreds of scholars and scientists vastly contributed to technology, science and medicine, later influencing the rise of European science during the Renaissance.[45]

Ibn Khaldun claimed in his work Muqaddimah (1377) that most Muslim contributions in ḥadîth were generally the works of Persians specifically:[46]

Most of the ḥadîth scholars who preserved traditions for the Muslims also were Persians, or Persian in language and upbringing, because the discipline was widely cultivated in the 'Irâq and the regions beyond. Furthermore all the scholars who worked in the science of the principles of jurisprudence were Persians. The same applies to speculative theologians and to most Qur'ân commentators. Only the Persians engaged in the task of preserving knowledge and writing systematic scholarly works. Thus, the truth of the following statement by the Prophet becomes apparent: 'If scholarship hung suspended in the highest parts of heaven, the Persians would attain it.'

New technology

With a new and easier writing system, and the introduction of paper, information was democratized to the extent that, for probably the first time in history, it became possible to make a living from only writing and selling books.[47] The use of paper spread from China into Muslim regions in the eighth century, arriving in Al-Andalus on the Iberian peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal) in the 10th century. It was easier to manufacture than parchment, less likely to crack than papyrus, and could absorb ink, making it difficult to erase and ideal for keeping records. Islamic paper makers devised assembly-line methods of hand-copying manuscripts to turn out editions far larger than any available in Europe for centuries.[48] It was from these countries that the rest of the world learned to make paper from linen.[49]

Education

The centrality of scripture and its study in the Islamic tradition helped to make education a central pillar of the religion in virtually all times and places in the history of Islam.[50] The importance of learning in the Islamic tradition is reflected in a number of hadiths attributed to Muhammad, including one that instructs the faithful to "seek knowledge, even in China".[50] This injunction was seen to apply particularly to scholars, but also to some extent to the wider Muslim public, as exemplified by the dictum of al-Zarnuji, "learning is prescribed for us all".[50] While it is impossible to calculate literacy rates in pre-modern Islamic societies, it is almost certain that they were relatively high, at least in comparison to their European counterparts.[50]

_2006.jpg.webp)

Education would begin at a young age with study of Arabic and the Quran, either at home or in a primary school, which was often attached to a mosque.[50] Some students would then proceed to training in tafsir (Quranic exegesis) and fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), which was seen as particularly important.[50] Education focused on memorization, but also trained the more advanced students to participate as readers and writers in the tradition of commentary on the studied texts.[50] It also involved a process of socialization of aspiring scholars, who came from virtually all social backgrounds, into the ranks of the ulema.[50]

For the first few centuries of Islam, educational settings were entirely informal, but beginning in the 11th and 12th centuries, the ruling elites began to establish institutions of higher religious learning known as madrasas in an effort to secure support and cooperation of the ulema.[50] Madrasas soon multiplied throughout the Islamic world, which helped to spread Islamic learning beyond urban centers and to unite diverse Islamic communities in a shared cultural project.[50] Nonetheless, instruction remained focused on individual relationships between students and their teacher.[50] The formal attestation of educational attainment, ijaza, was granted by a particular scholar rather than the institution, and it placed its holder within a genealogy of scholars, which was the only recognized hierarchy in the educational system.[50] While formal studies in madrasas were open only to men, women of prominent urban families were commonly educated in private settings and many of them received and later issued ijazas in hadith studies, calligraphy and poetry recitation.[51][52] Working women learned religious texts and practical skills primarily from each other, though they also received some instruction together with men in mosques and private homes.[51]

Madrasas were devoted principally to study of law, but they also offered other subjects such as theology, medicine, and mathematics.[53][54] The madrasa complex usually consisted of a mosque, boarding house, and a library.[53] It was maintained by a waqf (charitable endowment), which paid salaries of professors, stipends of students, and defrayed the costs of construction and maintenance.[53] The madrasa was unlike a modern college in that it lacked a standardized curriculum or institutionalized system of certification.[53]

Muslims distinguished disciplines inherited from pre-Islamic civilizations, such as philosophy and medicine, which they called "sciences of the ancients" or "rational sciences", from Islamic religious sciences.[50] Sciences of the former type flourished for several centuries, and their transmission formed part of the educational framework in classical and medieval Islam.[50] In some cases, they were supported by institutions such as the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, but more often they were transmitted informally from teacher to student.[50]

The University of Al Karaouine, founded in 859 AD, is listed in The Guinness Book Of Records as the world's oldest degree-granting university.[55] The Al-Azhar University was another early university (madrasa). The madrasa is one of the relics of the Fatimid caliphate. The Fatimids traced their descent to Muhammad's daughter Fatimah and named the institution using a variant of her honorific title Al-Zahra (the brilliant).[56] Organized instruction in the Al-Azhar Mosque began in 978.[57]

Law

Juristic thought gradually developed in study circles, where independent scholars met to learn from a local master and discuss religious topics.[58][59] At first, these circles were fluid in their membership, but with time distinct regional legal schools crystallized around shared sets of methodological principles.[59][60] As the boundaries of the schools became clearly delineated, the authority of their doctrinal tenets came to be vested in a master jurist from earlier times, who was henceforth identified as the school's founder.[59][60] In the course of the first three centuries of Islam, all legal schools came to accept the broad outlines of classical legal theory, according to which Islamic law had to be firmly rooted in the Quran and hadith.[60][61]

The classical theory of Islamic jurisprudence elaborates how scriptures should be interpreted from the standpoint of linguistics and rhetoric.[62] It also comprises methods for establishing authenticity of hadith and for determining when the legal force of a scriptural passage is abrogated by a passage revealed at a later date.[62] In addition to the Quran and sunnah, the classical theory of Sunni fiqh recognizes two other sources of law: juristic consensus (ijmaʿ) and analogical reasoning (qiyas).[63] It therefore studies the application and limits of analogy, as well as the value and limits of consensus, along with other methodological principles, some of which are accepted by only certain legal schools.[62] This interpretive apparatus is brought together under the rubric of ijtihad, which refers to a jurist's exertion in an attempt to arrive at a ruling on a particular question.[62] The theory of Twelver Shia jurisprudence parallels that of Sunni schools with some differences, such as recognition of reason (ʿaql) as a source of law in place of qiyas and extension of the notion of sunnah to include traditions of the imams.[64]

The body of substantive Islamic law was created by independent jurists (muftis). Their legal opinions (fatwas) were taken into account by ruler-appointed judges who presided over qāḍī's courts, and by maẓālim courts, which were controlled by the ruler's council and administered criminal law.[60][62]

Theology

Classical Islamic theology emerged from an early doctrinal controversy which pitted the ahl al-hadith movement, led by Ahmad ibn Hanbal, who considered the Quran and authentic hadith to be the only acceptable authority in matters of faith, against Mu'tazilites and other theological currents, who developed theological doctrines using rationalistic methods.[65] In 833 the caliph al-Ma'mun tried to impose Mu'tazilite theology on all religious scholars and instituted an inquisition (mihna), but the attempts to impose a caliphal writ in matters of religious orthodoxy ultimately failed.[65] This controversy persisted until al-Ash'ari (874–936) found a middle ground between Mu'tazilite rationalism and Hanbalite literalism, using the rationalistic methods championed by Mu'tazilites to defend most substantive tenets maintained by ahl al-hadith.[66] A rival compromise between rationalism and literalism emerged from the work of al-Maturidi (d. c. 944), and, although a minority of scholars remained faithful to the early ahl al-hadith creed, Ash'ari and Maturidi theology came to dominate Sunni Islam from the 10th century on.[66][67]

Philosophy

Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) played a major role in interpreting the works of Aristotle, whose ideas came to dominate the non-religious thought of the Christian and Muslim worlds. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, translation of philosophical texts from Arabic to Latin in Western Europe "led to the transformation of almost all philosophical disciplines in the medieval Latin world".[68] The influence of Islamic philosophers in Europe was particularly strong in natural philosophy, psychology and metaphysics, though it also influenced the study of logic and ethics.[68]

Metaphysics

Ibn Sina argued his "Floating man" thought experiment concerning self-awareness, in which a man prevented of sense experience by being blindfolded and free falling would still be aware of his existence.[69]

Epistemology

In epistemology, Ibn Tufail wrote the novel Hayy ibn Yaqdhan and in response Ibn al-Nafis wrote the novel Theologus Autodidactus. Both were concerning autodidacticism as illuminated through the life of a feral child spontaneously generated in a cave on a desert island.

Mathematics

Algebra

Persian mathematician Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī played a significant role in the development of algebra, arithmetic and Hindu-Arabic numerals. He has been described as the father[70][71] or founder[72][73] of algebra.

Another Persian mathematician, Omar Khayyam, is credited with identifying the foundations of Analytic geometry. Omar Khayyam found the general geometric solution of the cubic equation. His book Treatise on Demonstrations of Problems of Algebra (1070), which laid down the principles of algebra, is part of the body of Persian mathematics that was eventually transmitted to Europe.[74]

Yet another Persian mathematician, Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī, found algebraic and numerical solutions to various cases of cubic equations.[75] He also developed the concept of a function.[76]

Geometry

Islamic art makes use of geometric patterns and symmetries in many of its art forms, notably in girih tilings. These are formed using a set of five tile shapes, namely a regular decagon, an elongated hexagon, a bow tie, a rhombus, and a regular pentagon. All the sides of these tiles have the same length; and all their angles are multiples of 36° (π/5 radians), offering fivefold and tenfold symmetries. The tiles are decorated with strapwork lines (girih), generally more visible than the tile boundaries. In 2007, the physicists Peter Lu and Paul Steinhardt argued that girih from the 15th century resembled quasicrystalline Penrose tilings.[77][78][79][80] Elaborate geometric zellige tilework is a distinctive element in Moroccan architecture.[81] Muqarnas vaults are three-dimensional but were designed in two dimensions with drawings of geometrical cells.[82]

Trigonometry

Ibn Muʿādh al-Jayyānī is one of several Islamic mathematicians to whom the law of sines is attributed; he wrote his The Book of Unknown Arcs of a Sphere in the 11th century. This formula relates the lengths of the sides of any triangle, rather than only right triangles, to the sines of its angles.[83] According to the law,

where a, b, and c are the lengths of the sides of a triangle, and A, B, and C are the opposite angles (see figure).

Calculus

Alhazen discovered the sum formula for the fourth power, using a method that could be generally used to determine the sum for any integral power. He used this to find the volume of a paraboloid. He could find the integral formula for any polynomial without having developed a general formula.[84]

Natural sciences

Scientific method

Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) was a significant figure in the history of scientific method, particularly in his approach to experimentation,[85][86][87][88] and has been described as the "world's first true scientist".[89]

Avicenna made rules for testing the effectiveness of drugs, including that the effect produced by the experimental drug should be seen constantly or after many repetitions, to be counted.[90] The physician Rhazes was an early proponent of experimental medicine and recommended using control for clinical research. He said: "If you want to study the effect of bloodletting on a condition, divide the patients into two groups, perform bloodletting only on one group, watch both, and compare the results."[91]

Astronomy

In about 964 AD, the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi, writing in his Book of Fixed Stars, described a "nebulous spot" in the Andromeda constellation, the first definitive reference to what we now know is the Andromeda Galaxy, the nearest spiral galaxy to our galaxy.[92] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi invented a geometrical technique called a Tusi-couple, which generates linear motion from the sum of two circular motions to replace Ptolemy's problematic equant.[93] The Tusi couple was later employed in Ibn al-Shatir's geocentric model and Nicolaus Copernicus' heliocentric model[94] although it is not known who the intermediary is or if Copernicus rediscovered the technique independently. The names for some of the stars used, including Rigel and Vega, are still in use.[95]

Physics

Alhazen played a role in the development of optics. One of the prevailing theories of vision in his time and place was the emission theory supported by Euclid and Ptolemy, where sight worked by the eye emitting rays of light, and the other was the Aristotelean theory that sight worked when the essence of objects flows into the eyes. Alhazen correctly argued that vision occurred when light, traveling in straight lines, reflects off an object into the eyes. Al-Biruni wrote of his insights into light, stating that its velocity must be immense when compared to the speed of sound.[96]

Chemistry

The early Islamic period saw the establishment of some of the longest lived theoretical frameworks in alchemy and chemistry. The sulfur-mercury theory of metals, first attested in pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's Sirr al-khalīqa ("The Secret of Creation", c. 750–850) and in the Arabic writings attributed to Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (written c. 850–950),[97] would remain the basis of all theories of metallic composition until the eighteenth century.[98] Likewise, the Emerald Tablet, a compact and cryptic text that all later alchemists up to and including Isaac Newton (1642–1727) would regard as the foundation of their art, first occurs in the Sirr al-khalīqa and in one of the works attributed to Jābir.[99]

Substantial advances were also made in practical chemistry. The works attributed to Jābir, and those of the Persian alchemist and physician Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (854–925), contain the earliest known systematic classifications of chemical substances.[100] However, alchemists were not only interested in identifying and classifying chemical substances, but also in artificially creating them.[101] Significant examples from the medieval Islamic world include the synthesis of ammonium chloride from organic substances as described in the works attributed to Jābir,[102] and Abū Bakr al-Rāzī's experiments with vitriol, which would eventually lead to the discovery of mineral acids like sulfuric acid and nitric acid by thirteenth century Latin alchemists such as pseudo-Geber.[103]

Geodesy

Al-Biruni (973–1048) estimated the radius of the earth as 6339.6 km (modern value is c. 6,371 km), the best estimate at that time.[104]

Biology

In the cardiovascular system, Ibn al-Nafis in his Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon was the first known scholar to contradict the contention of the Galen School that blood could pass between the ventricles in the heart through the cardiac inter-ventricular septum that separates them, saying that there is no passage between the ventricles at this point.[105] Instead, he correctly argued that all the blood that reached the left ventricle did so after passing through the lung.[105] He also stated that there must be small communications, or pores, between the pulmonary artery and pulmonary vein, a prediction that preceded the discovery of the pulmonary capillaries of Marcello Malpighi by 400 years. The Commentary was rediscovered in the twentieth century in the Prussian State Library in Berlin; whether its view of the pulmonary circulation influenced scientists such as Michael Servetus is unclear.[105]

In the nervous system, Rhazes stated that nerves had motor or sensory functions, describing 7 cranial and 31 spinal cord nerves. He assigned a numerical order to the cranial nerves from the optic to the hypoglossal nerves. He classified the spinal nerves into 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 3 sacral, and 3 coccygeal nerves. He used this to link clinical signs of injury to the corresponding location of lesions in the nervous system.[106]

Modern commentators have likened medieval accounts of the "struggle for existence" in the animal kingdom to the framework of the theory of evolution. Thus, in his survey of the history of the ideas which led to the theory of natural selection, Conway Zirkle noted that al-Jahiz was one of those who discussed a "struggle for existence", in his Kitāb al-Hayawān (Book of Animals), written in the 9th century.[107] In the 13th century, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi believed that humans were derived from advanced animals, saying, "Such humans [probably anthropoid apes][108] live in the Western Sudan and other distant corners of the world. They are close to animals by their habits, deeds and behavior."[108] In 1377, Ibn Khaldun in his Muqaddimah stated, "The animal kingdom was developed, its species multiplied, and in the gradual process of Creation, it ended in man and arising from the world of the monkeys."[109]

Engineering

The Banū Mūsā brothers, in their Book of Ingenious Devices, describe an automatic flute player which may have been the first programmable machine.[110] The flute sounds were produced through hot steam and the user could adjust the device to various patterns so that they could get various sounds from it.[111]

Social sciences

Ibn Khaldun is regarded to be among the founding fathers of modern sociology,[n 1] historiography, demography,[n 1] and economics.[112][n 2]

Archiving was a respected position during this time in Islam though most of the governing documents have been lost over time. However, from correspondence and remaining documentation gives a hint of the social climate as well as shows that the archives were detailed and vast during their time. All letters that were received or sent on behalf of the governing bodies were copied, archived and noted for filing. The position of the archivist was seen as one that had to have a high level of devotion as they held the records of all pertinent transactions.[113]

Healthcare

Hospitals

_-_TIMEA.jpg.webp)

The earliest known Islamic hospital was built in 805 in Baghdad by order of Harun Al-Rashid, and the most important of Baghdad's hospitals was established in 982 by the Buyid ruler 'Adud al-Dawla.[114] The best documented early Islamic hospitals are the great Syro-Egyptian establishments of the 12th and 13th centuries.[114] By the tenth century, Baghdad had five more hospitals, while Damascus had six hospitals by the 15th century and Córdoba alone had 50 major hospitals, many exclusively for the military.[115]

The typical hospital was divided into departments such as systemic diseases, surgery, and orthopedics, with larger hospitals having more diverse specialties. "Systemic diseases" was the rough equivalent of today's internal medicine and was further divided into sections such as fever, infections and digestive issues. Every department had an officer-in-charge, a presiding officer and a supervising specialist. The hospitals also had lecture theaters and libraries. Hospitals staff included sanitary inspectors, who regulated cleanliness, and accountants and other administrative staff.[115] The hospitals were typically run by a three-man board comprising a non-medical administrator, the chief pharmacist, called the shaykh saydalani, who was equal in rank to the chief physician, who served as mutwalli (dean).[90] Medical facilities traditionally closed each night, but by the 10th century laws were passed to keep hospitals open 24 hours a day.[116]

For less serious cases, physicians staffed outpatient clinics. Cities also had first aid centers staffed by physicians for emergencies that were often located in busy public places, such as big gatherings for Friday prayers. The region also had mobile units staffed by doctors and pharmacists who were supposed to meet the need of remote communities. Baghdad was also known to have a separate hospital for convicts since the early 10th century after the vizier ‘Ali ibn Isa ibn Jarah ibn Thabit wrote to Baghdad's chief medical officer that "prisons must have their own doctors who should examine them every day". The first hospital built in Egypt, in Cairo's Southwestern quarter, was the first documented facility to care for mental illnesses. In Aleppo's Arghun Hospital, care for mental illness included abundant light, fresh air, running water and music.[115]

Medical students would accompany physicians and participate in patient care. Hospitals in this era were the first to require medical diplomas to license doctors.[117] The licensing test was administered by the region's government appointed chief medical officer. The test had two steps; the first was to write a treatise, on the subject the candidate wished to obtain a certificate, of original research or commentary of existing texts, which they were encouraged to scrutinize for errors. The second step was to answer questions in an interview with the chief medical officer. Physicians worked fixed hours and medical staff salaries were fixed by law. For regulating the quality of care and arbitrating cases, it is related that if a patient dies, their family presents the doctor's prescriptions to the chief physician who would judge if the death was natural or if it was by negligence, in which case the family would be entitled to compensation from the doctor. The hospitals had male and female quarters while some hospitals only saw men and other hospitals, staffed by women physicians, only saw women.[115] While women physicians practiced medicine, many largely focused on obstetrics.[118]

Hospitals were forbidden by law to turn away patients who were unable to pay.[116] Eventually, charitable foundations called waqfs were formed to support hospitals, as well as schools.[116] Part of the state budget also went towards maintaining hospitals.[115] While the services of the hospital were free for all citizens[116] and patients were sometimes given a small stipend to support recovery upon discharge, individual physicians occasionally charged fees.[115] In a notable endowment, a 13th-century governor of Egypt Al-Mansur Qalawun ordained a foundation for the Qalawun hospital that would contain a mosque and a chapel, separate wards for different diseases, a library for doctors and a pharmacy[119] and the hospital is used today for ophthalmology.[115] The Qalawun hospital was based in a former Fatimid palace which had accommodation for 8,000 people – [120] "it served 4,000 patients daily."[121] The waqf stated,

... The hospital shall keep all patients, men and women, until they are completely recovered. All costs are to be borne by the hospital whether the people come from afar or near, whether they are residents or foreigners, strong or weak, low or high, rich or poor, employed or unemployed, blind or sighted, physically or mentally ill, learned or illiterate. There are no conditions of consideration and payment, none is objected to or even indirectly hinted at for non-payment.[119]

Pharmacies

Arabic scholars used their natural and cultural resources to contribute to the strong development of pharmacology. They believed that God had provided the means for a cure for every disease. However, there was confusion about the nature of some ancient plants that existed during this time.[122]

A prominent figure that was influential in the development of pharmacy used the name Yūhannā ibn Māsawaiyh (circa 777-857). He was referred to as "The Divine Mesue" and "The Prince of Medicine" by European scholars. Māsawaiyh led the first private medical school in Baghdad and wrote three major pharmaceutical treatises.[123] These treatises consisted of works over compound medicines, humors, and pharmaceutical recipes that provided instructions on how they were to be prepared. In the Latin West, these works were typically published together under the title "Opera Medicinalia" and were broken up into "De simplicubus", "Grabadin", and "Canones universales". Although Māsawaiyh's influence was so significant that his writings became the most dominant source of pharmaceutical writings,[123] his exact identity remains unclear.[123]

In the past, all substances that were to be introduced into, on or near the human body were labeled as medicine, ranging from drugs, food, beverages, even perfumes to cosmetics. The earliest distinction between medicine and pharmacy as disciplines began in the seventh century, when pharmacists and apothecaries appeared in the first hospitals. Demand for drugs increased as the population increased. By the ninth century where pharmacy was established as an independent and well-defined profession by Muslim scholars. It is said by many historians that the opening of the first private pharmacy in the eighth century marks the independence of pharmacy from medicine.[122]

The emergence of medicine and pharmacy within the Islamic caliphate by the ninth century occurred at the same time as rapid expansion of many scientific institutions, libraries, schools, hospitals and then pharmacies in many Muslim cities. The rise of alchemy during the ninth century also played a vital role for early pharmacological development. While Arab pharmacists were not successful in converting non-precious metals into precious metals, their works giving details of techniques and lab equipment were major contributors to the development of pharmacy. Chemical techniques such as distillation, condensation, evaporation and pulverization were often used.

The Qur'an provided the basis for the development of professional ethics where the rise of ritual washing also influenced the importance of hygiene in pharmacology. Pharmacies were periodically visited by government inspectors called muhtasib, who checked to see that the medicines were mixed properly, not diluted and kept in clean jars. Work done by the muhtasib was carefully outlined in manuals that explained ways of examining and recognizing falsified drugs, foods and spices. It was forbidden for pharmacists to perform medical treatment without the presence of a physician, while physicians were limited to the preparation and handling of medications. It was feared that recipes would fall into the hands of someone without the proper pharmaceutical training. Licenses were required to run private practices. Violators were fined or beaten.

Medicine

The theory of Humorism was largely dominant during this time. Arab physician Ibn Zuhr provided proof that scabies is caused by the itch mite and that it can be cured by removing the parasite without the need for purging, bleeding or other treatments called for by humorism, making a break with the humorism of Galen and Ibn Sina.[118] Rhazes differentiated through careful observation the two diseases smallpox and measles, which were previously lumped together as a single disease that caused rashes.[124] This was based on location and the time of the appearance of the symptoms and he also scaled the degree of severity and prognosis of infections according to the color and location of rashes.[125] Al-Zahrawi was the first physician to describe an ectopic pregnancy, and the first physician to identify the hereditary nature of haemophilia.[126]

On hygienic practices, Rhazes, who was once asked to choose the site for a new hospital in Baghdad, suspended pieces of meat at various points around the city, and recommended building the hospital at the location where the meat putrefied the slowest.[91]

For Islamic scholars, Indian and Greek physicians and medical researchers Sushruta, Galen, Mankah, Atreya, Hippocrates, Charaka, and Agnivesa were pre-eminent authorities.[127] In order to make the Indian and Greek tradition more accessible, understandable, and teachable, Islamic scholars ordered and made more systematic the vast Indian and Greco-Roman medical knowledge by writing encyclopedias and summaries. Sometimes, past scholars were criticized, like Rhazes who criticized and refuted Galen's revered theories, most notably, the Theory of Humors and was thus accused of ignorance.[91] It was through 12th-century Arabic translations that medieval Europe rediscovered Hellenic medicine, including the works of Galen and Hippocrates, and discovered ancient Indian medicine, including the works of Sushruta and Charaka.[128][129] Works such as Ibn Sina's The Canon of Medicine were translated into Latin and disseminated throughout Europe. During the 15th and 16th centuries alone, The Canon of Medicine was published more than thirty-five times. It was used as a standard medical textbook through the 18th century in Europe.[130]

Surgery

Al-Zahrawi was a tenth century Arab physician. He is sometimes referred to as the "Father of surgery".[131] He describes what is thought to be the first attempt at reduction mammaplasty for the management of gynaecomastia[131] and the first mastectomy to treat breast cancer.[118] He is credited with the performance of the first thyroidectomy.[132] He wrote three textbooks on surgery, including "Manual of Medial Practitioners" which contains a catalog of 278 instruments used in surgery [95]

Commerce and travel

Apart from the Nile, Tigris, and Euphrates, navigable rivers were uncommon in the Middle East, so transport by sea was very important. Navigational sciences were highly developed, making use of a rudimentary sextant (known as a kamal). When combined with detailed maps of the period, sailors were able to sail across oceans rather than skirt along the coast. Muslim sailors were also responsible for reintroducing large, three-masted merchant vessels to the Mediterranean. The name caravel may derive from an earlier Arab boat known as the qārib.[133]

Many Muslims went to China to trade, and these Muslims began to have a great economic influence on the country. Muslims virtually dominated the import/export industry by the time of the Sung dynasty (960–1279).[134] Muhammad al-Idrisi created the Tabula Rogeriana, the best maps of the Middle Ages, used by various explorers such as Christopher Columbus and Vasco Da Gama for their voyages in America and India.[135]

Agriculture

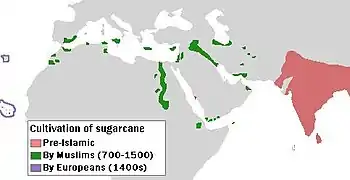

The Arabs of Al-Andalus exerted a large impact on Spanish agriculture, including the restoration of Roman-era aqueducts and irrigation channels, as well as the introduction of new technologies such as the acequias (derived from the qanats of Persia) and Persian gardens (such as at the Generalife). In Spain and Sicily, the Arabs introduced crops and foodstuffs from the Persia and India such as rice, sugarcane, oranges, lemons, bananas, saffron, carrots, apricots and eggplants, as well as restoring cultivation of olives and pomegranates from Greco-Roman times. The Palmeral of Elche in southern Spain is a UNESCO World Heritage site that is emblematic of the Islamic agricultural legacy in Europe.

Arts and culture

Literature and poetry

The 13th century Seljuq poet Rumi wrote some of the finest poetry in the Persian language and remains one of the best selling poets in America.[136][137] Other famous poets of the Persian language include Hafez (whose work was read by William Jones, Thoreau, Goethe, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Friedrich Engels), Saadi (whose poetry was cited extensively by Goethe, Hegel and Voltaire), Ferdowsi, Omar Khayyam and Amir Khusrow.

One Thousand and One Nights, an anthology of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in the Arabic language during the time of the Abbasid Caliphate, has had a large influence on Western and Middle Eastern literature and popular culture with such classics as Aladdin, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and Sinbad the Sailor. The folk-tale 'Sinbad the Sailor' even draws inspiration directly from Hellenistic literature like the Homeric epics (translated from Greek to Arabic in the 8th century CE) and Alexander Romances (tales of Alexander the Great popular in Europe, the Middle East and India).

Art

Manuscript illumination was an important art, and Persian miniature painting flourished in the Persianate world. Calligraphy, an essential aspect of written Arabic, developed in manuscripts and architectural decoration.

Music

The ninth and tenth centuries saw a flowering of Arabic music. Philosopher and esthete Al-Farabi,[138] at the end of the ninth century, established the foundations of modern Arabic music theory, based on the maqammat, or musical modes. His work was based on the music of Ziryab, the court musician of Andalusia. Ziryab was a renowned polymath, whose contributions to western civilization included formal dining, haircuts, chess, and more, in addition to his dominance of the world musical scene of the ninth century.[139]

Architecture

The Great Mosque of Kairouan (in Tunisia), the ancestor of all the mosques in the western Islamic world excluding Turkey and the Balkans,[140] is one of the best preserved and most significant examples of early great mosques. Founded in 670, it dates in its present form largely from the 9th century.[141] The Great Mosque of Kairouan is constituted of a three-tiered square minaret, a large courtyard surrounded by colonnaded porticos, and a huge hypostyle prayer hall covered on its axis by two cupolas.[140]

The Great Mosque of Samarra in Iraq was completed in 847. It combined the hypostyle architecture of rows of columns supporting a flat base, above which a huge spiralling minaret was constructed.

The beginning of construction of the Great Mosque at Cordoba in 785 marked the beginning of Islamic architecture in Spain and Northern Africa. The mosque is noted for its striking interior arches. Moorish architecture reached its peak with the construction of the Alhambra, the magnificent palace/fortress of Granada, with its open and breezy interior spaces adorned in red, blue, and gold. The walls are decorated with stylized foliage motifs, Arabic inscriptions, and arabesque design work, with walls covered in geometrically patterned glazed tiles.

Many traces of Fatimid architecture exist in Cairo today, the most defining examples include the Al Azhar University and the Al Hakim mosque.

Decline

Invasions

In 1206, Genghis Khan established a powerful dynasty among the Mongols of central Asia. During the 13th century, this Mongol Empire conquered most of the Eurasian land mass, including China in the east and much of the old Islamic caliphate (as well as Kievan Rus') in the west. The destruction of Baghdad and the House of Wisdom by Hulagu Khan in 1258 has been seen by some as the end of the Islamic Golden Age.[142]

The Ottoman conquest of the Arabic-speaking Middle East in 1516–17 placed the traditional heart of the Islamic world under Ottoman Turkish control. The rational sciences continued to flourish in the Middle East during the Ottoman period.[143]

Economics

To account for the decline of Islamic science, it has been argued that the Sunni Revival in the 11th and 12th centuries produced a series of institutional changes that decreased the relative payoff to producing scientific works. With the spread of madrasas and the greater influence of religious leaders, it became more lucrative to produce religious knowledge.

Ahmad Y. al-Hassan has rejected the thesis that lack of creative thinking was a cause, arguing that science was always kept separate from religious argument; he instead analyzes the decline in terms of economic and political factors, drawing on the work of the 14th-century writer Ibn Khaldun. Al-Hassan extended the golden age up to the 16th century, noting that scientific activity continued to flourish up until then.[3] Several other contemporary scholars have also extended it to around the 16th to 17th centuries, and analysed the decline in terms of political and economic factors.[1][2] More recent research has challenged the notion that it underwent decline even at that time, citing a revival of works produced on rational scientific topics during the seventeenth century.[144][145]

Current research has led to the conclusion that "the available evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that an increase in the political power of these elites caused the observed decline in scientific output."[146]

Culture

Economic historian Joel Mokyr has argued that Islamic philosopher al-Ghazali (1058–1111) "was a key figure in the decline in Islamic science", as his works contributed to rising mysticism and occasionalism in the Islamic world.[147] Against this view, Saliba (2007) has given a number of examples especially of astronomical research flourishing after the time of al-Ghazali.[148]

See also

- Baghdad School

- Christian influences in Islam

- Danish Golden Age

- Dutch Golden Age

- Emirate of Sicily

- Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain

- Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences

- Islamic astronomy

- Islamic studies

- List of Iranian scientists

- Ophthalmology in medieval Islam

- Spanish Golden Age

- Timeline of Islamic science and technology

Notes

-

- "...regarded by some Westerners as the true father of historiography and sociology".[n 3]

- "Ibn Khaldun has been claimed the forerunner of a great number of European thinkers, mostly sociologists, historians, and philosophers".(Boulakia 1971)

- "The founding father of Eastern Sociology".[n 4]

- "This grand scheme to find a new science of society makes him the forerunner of many of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries system-builders such as Vico, Comte and Marx." "As one of the early founders of the social sciences...".[n 5]

-

- "He is considered by some as a father of modern economics, or at least a major forerunner. The Western world recognizes Khaldun as the father of sociology but hesitates in recognizing him as a great economist who laid its very foundations. He was the first to systematically analyze the functioning of an economy, the importance of technology, specialization and foreign trade in economic surplus and the role of government and its stabilization policies to increase output and employment. Moreover, he dealt with the problem of optimum taxation, minimum government services, incentives, institutional framework, law and order, expectations, production, and the theory of value".Cosma, Sorinel (2009). "Ibn Khaldun's Economic Thinking". Ovidius University Annals of Economics (Ovidius University Press) XIV:52–57

- Gates, Warren E. (1967). "The Spread of Ibn Khaldûn's Ideas on Climate and Culture". Journal of the History of Ideas. 28 (3): 415–22. doi:10.2307/2708627. JSTOR 2708627.

- Dhaouadi, M. (1 September 1990). "Ibn Khaldun: The Founding Father of Eastern Sociology". International Sociology. 5 (3): 319–35. doi:10.1177/026858090005003007. S2CID 143508326.

- Haddad, L. (1 May 1977). "A Fourteenth-Century Theory of Economic Growth and Development". Kyklos. 30 (2): 195–213. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6435.1977.tb02006.x.

References

- George Saliba (1994), A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam, pp. 245, 250, 256–57. New York University Press, ISBN 0-8147-8023-7.

- King, David A. (1983). "The Astronomy of the Mamluks". Isis. 74 (4): 531–55. doi:10.1086/353360. S2CID 144315162.

- Hassan, Ahmad Y (1996). "Factors Behind the Decline of Islamic Science After the Sixteenth Century". In Sharifah Shifa Al-Attas (ed.). Islam and the Challenge of Modernity, Proceedings of the Inaugural Symposium on Islam and the Challenge of Modernity: Historical and Contemporary Contexts, Kuala Lumpur, August 1–5, 1994. International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization (ISTAC). pp. 351–99. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- Medieval India, NCERT, ISBN 81-7450-395-1

- Vartan Gregorian, "Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith", Brookings Institution Press, 2003, pp. 26–38 ISBN 0-8157-3283-X

- Islamic Radicalism and Multicultural Politics. Taylor & Francis. 2011-03-01. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-136-95960-8. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Science and technology in Medieval Islam" (PDF). History of Science Museum. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Ruggiero, Guido (15 April 2008). A Companion to the Worlds of the Renaissance, Guido Ruggiero. ISBN 9780470751619. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- Barlow, Glenna. "Arts of the Islamic World: the Medieval Period". Khan Academy. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Josias Leslie Porter, A Handbook for Travelers in Syria and Palestine, 1868, p. 49.

- "For six centuries and a half, through the golden age of Islam, lasted this Caliphate, till extinguished by the Osmanli sultans and in the death of the last of the blood of the house of Mahomet. The true Caliphate ended with the fall of Bagdad". New Outlook, Volume 45, 1892, p. 370.

- "the golden age of Islam, as Mr. Gilman points out, ended with Omar, the second of the Kalifs." The Literary World, Volume 36, 1887, p. 308.

- "The Ninth, Tenth and Eleventh centuries were the golden age of Islam" Life magazine, 9 May 1955, .

- so Linda S. George, The Golden Age of Islam, 1998: "from the last years of the eighth century to the thirteenth century."

- Arshad Khan, Islam, Muslims, and America: Understanding the Basis of Their Conflict, 2003, p. 19.

- Groth, Hans, ed. (2012). Population Dynamics in Muslim Countries: Assembling the Jigsaw. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 45. ISBN 978-3-642-27881-5.

- Rafiabadi, Hamid Naseem, ed. (2007). Challenges to Religions and Islam: A Study of Muslim Movements, Personalities, Issues and Trends, Part 1. Sarup & Sons. p. 1141. ISBN 978-81-7625-732-9.

- Salam, Abdus (1994). Renaissance of Sciences in Islamic Countries. p. 9. ISBN 978-9971-5-0946-0.

- "In Our Time – Al-Kindi, James Montgomery". bbcnews.com. 28 June 2012. Archived from the original on 2014-01-14. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- Brentjes, Sonja; Robert G. Morrison (2010). "The Sciences in Islamic societies". The New Cambridge History of Islam. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 569.

- Hill, Donald. Islamic Science and Engineering. 1993. Edinburgh Univ. Press. ISBN 0-7486-0455-3, p. 4

- "Nestorian – Christian sect". Archived from the original on 2016-10-28. Retrieved 2016-11-05.

- Rashed, Roshdi (2015). Classical Mathematics from Al-Khwarizmi to Descartes. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-415-83388-2.

- "Hunayn ibn Ishaq – Arab scholar". Archived from the original on 2016-05-31. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- O'Leary, Delacy (1949). How Greek Science Passed On To The Arabs. Nature. 163. p. 748. Bibcode:1949Natur.163Q.748T. doi:10.1038/163748c0. ISBN 978-1-317-84748-9. S2CID 35226072.

- Sarton, George. "History of Islamic Science". Archived from the original on 2016-08-12.

- Nancy G. Siraisi, Medicine and the Italian Universities, 1250–1600 (Brill Academic Publishers, 2001), p 134.

- Beeston, Alfred Felix Landon (1983). Arabic literature to the end of the Umayyad period. Cambridge University Press. p. 501. ISBN 978-0-521-24015-4. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- "Compendium of Medical Texts by Mesue, with Additional Writings by Various Authors". World Digital Library. Archived from the original on 2014-03-04. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (15 December 1998). "Eutychius of Alexandria". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2017-01-02. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- Anna Contadini, 'A Bestiary Tale: Text and Image of the Unicorn in the Kitāb naʿt al-hayawān (British Library, or. 2784)', Muqarnas, 20 (2003), 17–33 (p. 17), JSTOR 1523325.

- Bonner, Bonner; Ener, Mine; Singer, Amy (2003). Poverty and charity in Middle Eastern contexts. SUNY Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-7914-5737-5.

- Ruano, Eloy Benito; Burgos, Manuel Espadas (1992). 17e Congrès international des sciences historiques: Madrid, du 26 août au 2 septembre 1990. Comité international des sciences historiques. p. 527. ISBN 978-84-600-8154-8.

- Rémi Brague, Assyrians contributions to the Islamic civilization Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Britannica, Nestorian Archived 2014-03-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Foster, John (1939). The Church of the T'ang Dynasty. Great Britain: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 31.

The school was twice closed, in 431 and 489

- The School of Edessa Archived 2016-09-02 at the Wayback Machine, Nestorian.org.

- Frew, Donald (2012). "Harran: Last Refuge of Classical Paganism". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 13 (9): 17–29. doi:10.1558/pome.v13i9.17.

- "Harran University". Archived from the original on 2018-01-27.

- University of Tehran Overview/Historical Events Archived 2011-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Kaser, Karl The Balkans and the Near East: Introduction to a Shared History p. 135.

- Yazberdiyev, Dr. Almaz Libraries of Ancient Merv Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Dr. Yazberdiyev is Director of the Library of the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan, Ashgabat.

- Hyman and Walsh Philosophy in the Middle Ages Indianapolis, 1973, p. 204' Meri, Josef W. and Jere L. Bacharach, Editors, Medieval Islamic Civilization Vol. 1, A–K, Index, 2006, p. 304.

- Lewis, Bernard (2004). From Babel to Dragomans: Interpreting the Middle East. Oxford University Press. p. 44.

- Kühnel E., in Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenländischen Gesell, Vol. CVI (1956)

- Khaldun, Ibn (1981) [1377], Muqaddimah, 1, translated by Rosenthal, Franz, Princeton University Press, pp. 429–430

- "In Our Time – Al-Kindi, Hugh Kennedy". bbcnews.com. 28 June 2012. Archived from the original on 2014-01-14. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- "Islam's Gift of Paper to the West". Web.utk.edu. 2001-12-29. Archived from the original on 2015-05-03. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- Kevin M. Dunn, Caveman chemistry : 28 projects, from the creation of fire to the production of plastics. Universal-Publishers. 2003. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-58112-566-5. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- Jonathan Berkey (2004). "Education". In Richard C. Martin (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. MacMillan Reference USA.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 210. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- Berkey, Jonathan Porter (2003). The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600–1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 227.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 217. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- Hallaq, Wael B. (2009). An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 50.

- The Guinness Book Of Records, Published 1998, ISBN 0-553-57895-2, p. 242

- Halm, Heinz. The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning. London: The Institute of Ismaili Studies and I.B. Tauris. 1997.

- Donald Malcolm Reid (2009). "Al-Azhar". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 125. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- Hallaq, Wael B. (2009). An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–35.

- Vikør, Knut S. (2014). "Sharīʿah". In Emad El-Din Shahin (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 130. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- Calder, Norman (2009). "Law. Legal Thought and Jurisprudence". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2017-07-31. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- Ziadeh, Farhat J. (2009). "Uṣūl al-fiqh". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5.

- Kamali, Mohammad Hashim (1999). John Esposito (ed.). Law and Society. The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press (Kindle edition). pp. 121–22.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). pp. 130–31. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- Blankinship, Khalid (2008). Tim Winter (ed.). The early creed. The Cambridge Companion to Classical Islamic Theology. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 53.

- Tamara Sonn (2009). "Tawḥīd". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5.

- Dag Nikolaus Hasse (2014). "Influence of Arabic and Islamic Philosophy on the Latin West". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2017-10-20. Retrieved 2017-07-31.

- "In Our Time: Existence". bbcnews.com. 8 November 2007. Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- Boyer, Carl B., 1985. A History of Mathematics, p. 252. Princeton University Press.

- S Gandz, The sources of al-Khwarizmi's algebra, Osiris, i (1936), 263–277

- https://eclass.uoa.gr/modules/document/file.php/MATH104/20010-11/HistoryOfAlgebra.pdf, "The first true algebra text which is still extant is the work on al-jabr and al-muqabala by Mohammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, written in Baghdad around 825"

- Esposito, John L. (2000-04-06). The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-19-988041-6.

- Mathematical Masterpieces: Further Chronicles by the Explorers, p. 92

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Sharaf al-Din al-Muzaffar al-Tusi", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Victor J. Katz, Bill Barton; Barton, Bill (October 2007). "Stages in the History of Algebra with Implications for Teaching". Educational Studies in Mathematics. 66 (2): 185–201 [192]. doi:10.1007/s10649-006-9023-7. S2CID 120363574.

- Peter J. Lu; Paul J. Steinhardt (2007). "Decagonal and Quasi-crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture". Science. 315 (5815): 1106–10. Bibcode:2007Sci...315.1106L. doi:10.1126/science.1135491. PMID 17322056. S2CID 10374218.

- "Advanced geometry of Islamic art". bbcnews.com. 23 February 2007. Archived from the original on 2013-02-19. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- Ball, Philip (22 February 2007). "Islamic tiles reveal sophisticated maths". News@nature. doi:10.1038/news070219-9. S2CID 178905751. Archived from the original on 2013-08-01. Retrieved July 26, 2013. "Although they were probably unaware of the mathematical properties and consequences of the construction rule they devised, they did end up with something that would lead to what we understand today to be a quasi-crystal."

- "Nobel goes to scientist who knocked down 'Berlin Wall' of chemistry". cnn.com. 16 October 2011. Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- Castera, Jean Marc; Peuriot, Francoise (1999). Arabesques. Decorative Art in Morocco. Art Creation Realisation. ISBN 978-2-86770-124-5.

- van den Hoeven, Saskia, van der Veen, Maartje (2010). "Muqarnas-Mathematics in Islamic Arts" (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Muadh Al-Jayyani". University of St.Andrews. Archived from the original on 2016-05-29. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Katz, Victor J. (1995). "Ideas of Calculus in Islam and India". Mathematics Magazine. 68 (3): 163–74 [165–69, 173–74]. doi:10.2307/2691411. JSTOR 2691411.

- El-Bizri, Nader, "A Philosophical Perspective on Ibn al-Haytham's Optics", Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 15 (2005-08-05), 189–218

- Haq, Syed (2009). "Science in Islam". Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. ISSN 1703-7603. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- Sabra, A.I. (1989). The Optics of Ibn al-Haytham. Books I–II–III: On Direct Vision. London: The Warburg Institute, University of London. pp. 25–29. ISBN 0-85481-072-2.

- Toomer, G.J. (1964). "Review: Ibn al-Haythams Weg zur Physik by Matthias Schramm". Isis. 55 (4): 463–65. doi:10.1086/349914.

- Al-Khalili, Jim (2009-01-04). "BBC News". Archived from the original on 2015-05-03. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- "The Islamic roots of modern pharmacy". aramcoworld.com. Archived from the original on 2016-05-18. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- Hajar, R (2013). "The Air of History (Part IV): Great Muslim Physicians Al Rhazes". Heart Views. 14 (2): 93–95. doi:10.4103/1995-705X.115499. PMC 3752886. PMID 23983918.

- Henbest, N.; Couper, H. (1994). The guide to the galaxy. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-45882-5.

- Craig G. Fraser, 'The cosmos: a historical perspective', Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006 p. 39

- George Saliba, 'Revisiting the Astronomical Contacts Between the World of Islam and Renaissance Europe: The Byzantine Connection', 'The occult sciences in Byzantium', 2006, p. 368

- Alexakos, Konstantinos; Antoine, Wladina (2005). "The Golden Age of Islam and Science Teaching: Teachers and students develop a deeper understanding of the foundations of modern science by learning about the contributions of Arab-Islamic scientists and scholars". The Science Teacher. 72 (3): 36–39. ISSN 0036-8555. JSTOR 24137786.

- J J O'Connor; E F Robertson (1999). "Abu Arrayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Kraus, Paul (1942–1943). Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque. Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. ISBN 9783487091150. OCLC 468740510. vol. II, p. 1, note 1; Weisser, Ursula (1980). Das "Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung" von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana. Berlin: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110866933. p. 199. On the dating and historical background of the Sirr al-khalīqa, see Kraus 1942−1943, vol. II, pp. 270–303; Weisser 1980, pp. 39–72. On the dating of the writings attributed to Jābir, see Kraus 1942−1943, vol. I, pp. xvii–lxv.

- Norris, John (2006). "The Mineral Exhalation Theory of Metallogenesis in Pre-Modern Mineral Science". Ambix. 53 (1): 43–65. doi:10.1179/174582306X93183.

- Weisser, Ursula (1980). Das "Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung" von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana. Berlin: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110866933. p. 46. On Newton's alchemy, see Newman, William R. (2019). Newton the Alchemist: Science, Enigma, and the Quest for Nature's Secret Fire. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691174877.

- Karpenko, Vladimír; Norris, John A. (2002). "Vitriol in the History of Chemistry". Chemické listy. 96 (12): 997–1005.

- See Newman, William R. (2004). Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226575247.

- Kraus, Paul (1942–1943). Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque. Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. ISBN 9783487091150. OCLC 468740510. Vol. II, pp. 41–42.

- Karpenko, Vladimír; Norris, John A. (2002). "Vitriol in the History of Chemistry". Chemické listy. 96 (12): 997–1005.

- Pingree, David (1985). "Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān iv. Geography". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Columbia University. ISBN 978-1-56859-050-9.

- West, John (2008). "Ibn al-Nafis, the pulmonary circulation, and the Islamic Golden Age". Journal of Applied Physiology. 105 (6): 1877–80. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.91171.2008. PMC 2612469. PMID 18845773.

- Souayah, N; Greenstein, JI (2005). "Insights into neurologic localization by Rhazes, a medieval Islamic physician". Neurology. 65 (1): 125–28. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000167603.94026.ee. PMID 16009898. S2CID 36595696.

- Zirkle, Conway (25 April 1941). "Natural Selection before the "Origin of Species"". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 84 (1): 71–123. JSTOR 984852.

- Farid Alakbarov (Summer 2001). A 13th-Century Darwin? Tusi's Views on Evolution Archived 2010-12-13 at the Wayback Machine, Azerbaijan International 9 (2).

- "Rediscovering Arabic Science". Saudi Aramco Magazine. Archived from the original on 2014-10-30. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Koetsier, Teun (2001), "On the prehistory of programmable machines: musical automata, looms, calculators", Mechanism and Machine Theory, 36 (5): 589–603, doi:10.1016/S0094-114X(01)00005-2.

- Banu Musa (authors), Donald Routledge Hill (translator) (1979), The book of ingenious devices (Kitāb al-ḥiyal), Springer, pp. 76–77, ISBN 978-90-277-0833-5

-

- Spengler, Joseph J. (1964). "Economic Thought of Islam: Ibn Khaldun". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 6 (3): 268–306. doi:10.1017/s0010417500002164. JSTOR 177577. .

• Boulakia, Jean David C. (1971). "Ibn Khaldûn: A Fourteenth-Century Economist". Journal of Political Economy. 79 (5): 1105–18. doi:10.1086/259818. JSTOR 1830276. S2CID 144078253..

- Spengler, Joseph J. (1964). "Economic Thought of Islam: Ibn Khaldun". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 6 (3): 268–306. doi:10.1017/s0010417500002164. JSTOR 177577. .

- Posner, Ernest (1972). "Archives in Medieval Islam". American Archivist. 35 (3–4): 291–315. doi:10.17723/aarc.35.3-4.x1546224w7621152.

- Savage-Smith, Emilie, Klein-Franke, F. and Zhu, Ming (2012). "Ṭibb". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1216.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "The Islamic Roots of the Modern Hospital". aramcoworld.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-21. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Rise and spread of Islam. Gale. 2002. p. 419. ISBN 978-0-7876-4503-8.

- Alatas, Syed Farid (2006). "From Jami'ah to University: Multiculturalism and Christian–Muslim Dialogue". Current Sociology. 54 (1): 112–32. doi:10.1177/0011392106058837. S2CID 144509355.

- "Pioneer Muslim Physicians". aramcoworld.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-21. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Philip Adler; Randall Pouwels (2007). World Civilizations. Cengage Learning. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-111-81056-6. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- Bedi N. Şehsuvaroǧlu (2012-04-24). "Bīmāristān". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; et al. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Archived from the original on 2016-09-20. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- Mohammad Amin Rodini (7 July 2012). "Medical Care in Islamic Tradition During the Middle Ages" (PDF). International Journal of Medicine and Molecular Medicine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- King, Anya (2015). "The New materia medica of the Islamicate Tradition: The Pre-Islamic Context". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 135 (3): 499–528. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.135.3.499. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.135.3.499.

- De Vos, Paula (2013). "The "Prince of Medicine": Yūḥannā ibn Māsawayh and the Foundations of the Western Pharmaceutical Tradition". Isis. 104 (4): 667–712. doi:10.1086/674940. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 10.1086/674940. PMID 24783490. S2CID 25175809.

- "Abu Bakr Mohammad Ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Rhazes) (c. 865-925)". sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2015-05-06. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- "Rhazes Diagnostic Differentiation of Smallpox and Measles". ircmj.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- Cosman, Madeleine Pelner; Jones, Linda Gale (2008). Handbook to Life in the Medieval World. Handbook to Life Series. 2. Infobase Publishing. pp. 528–30. ISBN 978-0-8160-4887-8.

- Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), p. 3.

- K. Mangathayaru (2013). Pharmacognosy: An Indian perspective. Pearson education. p. 54. ISBN 978-93-325-2026-4.

- Lock, Stephen (2001). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 607. ISBN 978-0-19-262950-0.

- A.C. Brown, Jonathan (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-78074-420-9.

- Ahmad, Z. (St Thomas' Hospital) (2007), "Al-Zahrawi – The Father of Surgery", ANZ Journal of Surgery, 77 (Suppl. 1): A83, doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04130_8.x, S2CID 57308997

- Ignjatovic M: Overview of the history of thyroid surgery. Acta Chir Iugosl 2003; 50: 9–36.

- "History of the caravel". Nautarch.tamu.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-05-03. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- "Islam in China". bbcnews.com. 2 October 2002. Archived from the original on 2016-01-06. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Houben, 2002, pp. 102–104.

- Haviland, Charles (2007-09-30). "The roar of Rumi – 800 years on". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2012-07-30. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- "Islam: Jalaluddin Rumi". BBC. 2009-09-01. Archived from the original on 2011-01-23. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Amber Haque (2004), "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists", Journal of Religion and Health 43 (4): 357–377 [363].

- Epstein, Joel, The Language of the Heart (2019, Juwal Publishing, ISBN 978-1070100906)

- John Stothoff Badeau and John Richard Hayes, The Genius of Arab civilization: source of Renaissance. Taylor & Francis. 1983-01-01. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-262-08136-8. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- "Great Mosque of Kairouan (Qantara mediterranean heritage)". Qantara-med.org. Archived from the original on 2015-02-09. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- Cooper, William W.; Yue, Piyu (2008). Challenges of the Muslim world: present, future and past. Emerald Group Publishing. ISBN 978-0-444-53243-5. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- El-Rouhayeb, Khaled (2015). Islamic Intellectual History in the Seventeenth Century: Scholarly Currents in the Ottoman Empire and the Maghreb. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-1-107-04296-4.

- El-Rouayheb, Khaled (2008). "The Myth of "The Triumph of Fanaticism" in the Seventeenth-Century Ottoman Empire". Die Welt des Islams. 48 (2): 196–221. doi:10.1163/157006008x335930.

- El-Rouayheb, Khaled (2006). "Opening the Gate of Verification: The Forgotten Arab-Islamic Florescence of the 17th Century". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 38 (2): 263–81. doi:10.1017/s0020743806412344.

- "Religion and the Rise and Fall of Islamic Science". scholar.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- "Mokyr, J.: A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy. (eBook and Hardcover)". press.princeton.edu. p. 67. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- "The Fountain Magazine – Issue – Did al-Ghazali Kill the Science in Islam?". www.fountainmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-30. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

Further reading

- George Makdisi "Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West". Journal of the American Oriental Society 109, no.2 (1982)

- Josef W. Meri (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96690-6. p. 1088.

- Tamara Sonn: Islam: A Brief History. Wiley 2011, ISBN 978-1-4443-5898-8, pp. 39–79 (online copy, p. 39, at Google Books)

- Maurice Lombard: The Golden Age of Islam. American Elsevier 1975

- George Nicholas Atiyeh; John Richard Hayes (1992). The Genius of Arab Civilization. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-3485-5, 978-0-8147-3485-8. p. 306.

- Falagas, M. E.; Zarkadoulia, Effie A.; Samonis, George (1 August 2006). "Arab science in the golden age (750–1258 C.E.) and today". The FASEB Journal. 20 (10): 1581–86. doi:10.1096/fj.06-0803ufm. PMID 16873881. S2CID 40960150.

- Starr, S. Frederick (2015). Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane. Princeton University. ISBN 978-0-691-16585-1.

- Allsen, Thomas T. (2004). Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60270-9.

- Dario Fernandez-Morera (2015) The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise. Muslims, Christians, and Jews under Islamic Rule in Medieval Spain. ISI Books ISBN 978-1-61017-095-6 (hardback)

- Joel Epstein (2019) The Language of the Heart Juwal Publications ISBN 978-1070100906

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Islamic Golden Age. |

- Islamicweb.com: History of the Golden Age

- Khamush.com: Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate – Chapter 5, by Gaston Wiet.

- U.S. Library of Congress.gov: The Kirkor Minassian Collection – contains examples of Islamic book bindings.