History of slavery in Pennsylvania

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported African slaves for workers; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Slavery was documented in this area as early as 1639.[1] William Penn and the colonists who settled Pennsylvania tolerated slavery, but the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

During the American Revolutionary War, Pennsylvania passed the Gradual Abolition Act (1780), the first such law in the new United States. Pennsylvania's law established as free those children born to slave mothers after that date. They had to serve lengthy periods of indentured servitude until age 28 before becoming fully free as adults. Emancipation proceeded and, by 1810 there were fewer than 1,000 slaves in the Commonwealth. None appeared in records after 1847.

British colony

After the founding of Pennsylvania in 1682, Philadelphia became the region's main port for the import of slaves. Throughout the colony and state's history, the majority of slaves lived in or near that city. Although most slaves were brought into the colony in small groups, in December 1684 the slave ship Isabella unloaded a cargo of 150 slaves from Africa. Accurate population figures do not exist for the early colonial period, but more demographic data is available after 1750. Estate records from 1682 to 1705 reveal that during this period, less than 7% of families in Philadelphia owned slaves.[2]

The first recorded formal protest against slavery, the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery, was signed by German members of a Quaker congregation. Although a number of Quakers were slave-owners, the Quakers as a group continued a protest against slavery. (See: Quakers in the Abolition Movement)

William Penn, the proprietor of the Province of Pennsylvania, held 12 slaves as workers on his estate, Pennsbury. They took part in construction of the main house and outbuildings. Penn left the colony in 1701, and never returned.

Laws

Until 1700 slaves came under the same laws that governed indentured servants. Beginning that year, the colony passed laws to try slaves and free blacks in non-jury courts, rather than under the same terms as other residents of the colony.

Under An Act for the Better Regulating of Negroes in this Province (March 5, 1725–1726), numerous provisions restricted slaves and free blacks.

- (Section I) if a slave was sentenced to death, the owner would be paid full value for the slave.

- (Sec II) Duties on slaves transported from other colonies for a crime are doubled.

- (Sec III) If a slave is freed, the owner must have a sureties bond of £30 to indemnify the local government in case he/she becomes incapable of supporting himself.

- (Sec IV) A freed slave fit but unwilling to work shall be bound out [as an indentured servant] on a year-to-year basis as the magistrates see fit. And their male children may be bound out until 24 and women children until 21.

- (Sec V) Free Negroes and Mulattoes cannot entertain, barter or trade with slaves or bound servants in their homes without leave and consent of their master under penalty of fines and whipping.

- (Sec VI) If fines cannot be paid, the freeman can be bound out.

- (Sec VII) A minister, pastor, or magistrate who marries a negro to a white is fined £100.

- (Sec VIII) If a white cohabits under pretense of being married with a negro, the white will be fined 30 shillings or bound out for seven years, and the white person's children will be bound out until 31. If a free negro marries a white, they become slaves during life. If a free negro commits fornication or adultery with a white, they are bound out for 7 years. The white person shall be punished for fornication or adultery under existing law.

- (Sec IX) Slaves tippling or drinking at or near a liquor shop or out after nine, 10 lashes.

- (Sec X) If more than 10 miles from their master's home, 10 lashes.

- (Sec XI) Masters not allowed to have their slaves to find and or go to work at their own will receive a 20 shilling fine.

- (Sec XII) Harboring or concealing a slave: a 30 shillings a day fine.

- (Sec XIII) Fine to be used to pay the owners of slaves sentenced to death. This law was repealed in 1780.[3]

During the colonial period, Pennsylvania passed a series of laws to restrict the slave trade. Beginning in 1700, it imposed duties on the import of slaves. The Board of Trade in England rescinded the duties, which the Pennsylvania Assembly reimposed: 1700: 20 shillings per slave, 1750: 40 shillings, 1712: £20, 1715 to 1722 and again in 1725: £5: each time the Law was overturned in London it was re-established in Pennsylvania.[4]

Conditions

In the first years of the colony, masters used slaves to clear land and build housing. Once the colony was established, the slaves took on a wider variety of jobs. In Philadelphia, where the majority of slaves lived, many were household servants, while others were trained in different trades and as artisans. In 1767, the wealthiest 10% of the population owned 44% of slaves; the poorest 50% of residents owned 5% of slaves. The wealthy used them as domestic servants and expressions of their wealth. Middling merchants kept slaves as servants, while also using some as apprentices in the business, or other jobs also occupied by indentured servants. As Philadelphia was a port city, many slaves were used in jobs associated with shipping. They worked as gangs in rope-walks, and learned sail making. Some sailors took slaves with them as workers so that the sailors could increase their share of profits, as the slaves would be given none.[5]

In rural areas, slaves generally worked as household servants or farmhands, and sometimes both depending on need, just as farm families took on all jobs. In Southeastern Pennsylvania, iron masters who owned slaves sometimes leased them out locally to work at charcoal manufacture and the surface mining of limestone and iron ore.[6]

Due to lack of sanitation and understanding about transmission of disease, Philadelphia was an unhealthy place during the colonial period, with a death rate of 58 per 1,000. Many slaves were among those who died early. As more males were imported than females at the time, family formation was limited. Without the continued import of new slaves, the slave population would not have increased.[7]

Resistance and abolition

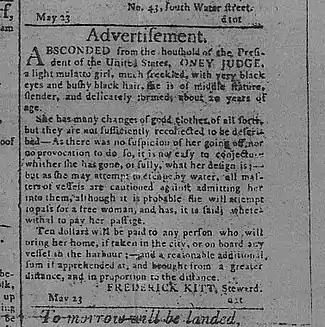

By the time of the French and Indian War, the number of slaves in the state was at its highest. More had been imported in the mid-18th century, as the improving economy in the British Isles had resulted in fewer immigrants coming as indentured servants. Given continued Anglo-European immigration to the colony, though, slaves as a percentage of the total population decreased over time.[2] By the time of the American Revolution, slavery had decreased in importance as a labor source in Pennsylvania. The Quakers had long disapproved of the practice on religious grounds, as did Methodists and Baptists, active in the Great Awakening. In addition, the wave of recent German immigrants were opposed to it based on their religious and political beliefs. The Scots-Irish, also recent immigrants, generally settled in the backcountry on subsistence farms. As a group, they were too poor to buy slaves. In the late colonial period, people found it economically viable to pay for free labor. Another factor against slavery was the rising fervor of revolutionary ideals about the rights of man.[1]

Religious resistance to slavery and the slave-import taxes led the colony to ban slave imports in 1767. Slaveholders among the state's Founding Fathers included Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, Robert Morris, Edmund Physick and Samuel Mifflin. Franklin and Dickinson both gradually became supporters of abolition.

In 1780 Pennsylvania passed the first state Abolition Act in the United States under the leadership of George Bryan. It followed Vermont's abolition of slavery in its constitution of 1777. The Pennsylvania law ended slavery through gradual emancipation, saying:

That all Persons, as well Negroes, and Mulattos, as others, who shall be born within this State, from and after the Passing of this Act, shall not be deemed and considered as Servants for Life or Slaves; and that all Servitude for Life or Slavery of Children in Consequence of the Slavery of their Mothers, in the Case of all Children born within this State from and after the passing of this Act as aforesaid, shall be, and hereby is, utterly taken away, extinguished and for ever abolished.[8]

This act repealed the acts of 1700 and 1726 that had established separate courts and laws specific to Negroes. At this point, slaves were given the same rights as bound servants. Free Negroes had, in theory, the same rights as free Whites. The law did not free those approximately 6,000 persons who were already slaves in Pennsylvania. Children born to slave mothers had to serve as indentured servants to their mother's master until they were 28 years old. [8] (Such indentures could be sold.)

Pennsylvania became a state with an established African-American community. Black activists understood the importance of writing about freedom, and were important participants in abolitionist groups. They gained access to papers run by anti-slave supporters and printed articles about freedom. Anti-slavery pamphlets and writings were rare in the South, but widely distributed in the state of Pennsylvania. African-American activists also began to hold meetings around the state, which were sometimes disrupted by white rioters. The activists continued to hold their meetings. African-American activists also contributed to operations of the Underground Railroad, and aiding slaves to freedom in the state. The activists created the Vigilant Association in Philadelphia, which helped refugees from slavery to escape from masters and get resettled in free states.[9]

Decline of slavery

In 1780, the abolition act provided for the children of slave mothers to remain in servitude until the age of 28. Section 2 of the Act stated, "Every negro and mulatto child born within this state after the passing of this act as aforesaid who would in case this act had not been made, have been born a servant for years or life or a slave, shall be deemed to be and shall be, by virtue of this act the servant of such a person or his or her assigns who would in such case have been entitled to the service of such child until such child shall attain unto the age of twenty-eight years...".[8] It required that they and children of African-descended indentured servants be registered at birth. Some Quarter Sessions records of Friends Meetings include births of children identified as mulatto or black.[10]

The federal censuses reflect the decline in slavery. In addition to the effects of the state law, many Pennsylvania masters freed their slaves in the first two decades after the Revolution, as did Benjamin Franklin. They were inspired by revolutionary ideals as well as continued appeals by Quaker and Methodist clergy for manumission of slaves. The first U.S. Census in 1790 recorded 3,737 slaves in Pennsylvania (36% of the Black population). By 1810, the total Black population had more than doubled, but the percentage who were slaves had dropped to 3%; only 795 slaves were listed in the state.[11]

The following table represents the growth in Pennsylvania's free black population and decline of its slave population.[12]

| Year | Free Blacks | Total Blacks | Slaves | Percentage of Blacks Free |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 6,537 | 10,274 | 3,737 | 63.62 |

| 1810 | 22,492 | 23,287 | 795 | 96.58 |

| 1820 | 30,202 | 30,413 | 211 | 99.31 |

| 1840 | 47,854 | 47,918 | 64 | 99.87 |

| 1860 | 56,949 | 56,949 | 0 | 100.00 |

See also

References

- Turner, E. R. The Negro In Pennsylvania, Slavery-Servitude-Freedom, 1639-1861, (1912), p. 1

- Trotter, J. W. and Smith, E. L, ed. African Americans in Pennsylvania (1997), p. 44

- Statutes at Large: Table of Contents

- Turner, The Negro In Pennsylvania (1912), pp. 3-6

- Trotter and Smith, African Americans in Pennsylvania (1997), pp. 55-58

- Walker Joseph E "Negro Labor in the Charcoal Iron Industry of Southeastern Pennsylvania", The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 93, No. 4 (October 1969), pp. 466-486; via JSTOR

- Trotter and Smith, African Americans in Pennsylvania (1997), p. 69

- "1780: AN ACT FOR THE GRADUAL ABOLITION OF SLAVERY", Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania

- Newman, Richard S. (7 September 2011). "'Lucky to be born in Pennsylvania': Free Soil, Fugitive Slaves and the Making of Pennsylvania's Anti-Slavery Borderland". America: History and Life.

- Robert L. Baker, "Slavery, Anti-Slavery and the Underground Railroad in Centre County, Pennsylvania", Historical Records Imaging Project, Centre County Government, accessed 16 August 2012

- Trotter and Smith, ed. African Americans in Pennsylvania (1997) p. 77

- Ira Berlin (2003), pp. 276-278

External links

- "Slavery in Pennsylvania", Slavery in the North website

- "Pennsylvania slavery by the numbers", USHistory.org

- "African Americans in Pennsylvania", President's House Museum Center

- Edward Raymond Turner, The Negro in Pennsylvania Slavery-Servitude-Freedom, American Historical Association, 1911

Bibliography

- Berlin, Ira. Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves. (2003) ISBN 0-674-01061-2