History of the Assyrian people

The history of the Assyrian people begins with the appearance of Akkadian speaking peoples in Mesopotamia at some point between 3500 and 3000 BC, followed by the formation of Assyria in the 25th century BC. During the early Bronze Age period Sargon of Akkad united all the native Semitic-speakers and the Sumerians of Mesopotamia (including the Assyrians) under the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC). Assyria essentially existed as part of a unified Akkadian nation for much of the period from the 24th century BC to the 22nd century BC, and a nation-state from the mid 21st century BC until its destruction as an independent state between 615–599 BC.

The Assyrians are culturally, linguistically, genetically and ethnically distinct from their neighbours in the Middle East – the Arabs, Syrians, Persians/Iranians, Kurds, Jews, Turks, Israelis, Azeris, Shabaks, Yezidis, Kawliya, Mandeans and Armenians.

Assyrian nationalism emphasizes their indigeneity to the Assyrian homeland, together with cultural, historical and ethnic Assyrian continuity since the Iron Age Neo-Assyrian Empire, and Achaemenid Persian, Greek, Roman, Parthian, and Sassanid ruled Athura/Assuristan. Assyria was a land stretching from Tkrit in the south to Amida, Kultepe and Harran in the north, and from Edessa in the west to the border of Persia (Iran) in the east.

The Assyrians are indigenous to modern northern Iraq, southeast Turkey, northwest Iran and northeast Syria.[1] These modern areas encompassed ancient Assyria between the 21st century BC and 7th century AD. Much of this land is now also inhabited by much later arriving Kurds, Arabs, Turks, Yezidis, Armenians, Shabakis, Turcomans and others.

The Assyrians are a Semitic people, with many (estimates range between 575,000 and 1,000,000) still speaking, reading and writing Akkadian influenced dialects of East Aramaic. Today they are a Christian people, with most being followers of the Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Ancient Church of the East, Assyrian Pentecostal Church and Assyrian Evangelical Church.

Ancient Assyria

In prehistoric times, the region that was to become known as Assyria (and Subartu) was home to a Neanderthal culture such as has been found at the Shanidar Cave. The earliest Neolithic sites in Assyria were the Jarmo culture c. 7100 BC and Tell Hassuna, the centre of the Hassuna culture, c. 6000 BC.

The cities of Assur (also spelled Ashur or Aššur) and Nineveh, together with a number of other towns and cities, existed as early as the 26th century BC, although they appear to have been Sumerian-ruled administrative centers at this time, rather than independent states. The Assyrian king list records kings dating from the 25th century BC onwards, the earliest being Tudiya, who was a contemporary of Ibrium of Ebla. However, many of these early kings would have been local rulers, and from the late 24th century BC to the early 22nd century BC, usually subject to the Akkadian Empire based in the city of Akkad, which united all of the Akkadian speaking Semites (including the Assyrians) under one rule.. The Sumerians were eventually absorbed into the Akkadian (Assyro-Babylonian) population.[2][3]

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, the Akkadians once more fragmented into smaller nation-states, with Assyria coming to dominate northern Mesopotamia, and states such as Ur, Kish, Isin and Larsa the south. In the 18th century BC the south Mesopotamian states were subsumed into a new power, that of Babylonia. However, Babylonia unlike Assyria, was founded and originally ruled by non indigenous Amorites, and was to be more often than not ruled by other waves of non indigenous peoples such as Kassites, Hittites, Elamites, Arameans and Chaldeans, as well as by the indigenous Assyrians.

Assyria was for most of this period a powerful and highly advanced nation, and a major center of Mesopotamian civilization and Mesopotamian religion. Assyria had three periods of empire; the Old Assyrian Empire (2025–1750 BC) which saw it emerge as the most powerful state in the region, extending colonies into southeast Anatolia, the northern Levant, central Mesopotamia and northwestern Ancient Iran. The Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC) saw Assyria emerge as the most powerful military and political force in the known world, destroying the Mitanni-Hurrian empire, largely annexing the Hittite Empire, forcing the Egyptian Empire from the region, conquering Babylonia and besting the Elamites, Kassites, Phrygians, Amorites, Arameans, Phoenicians and Cilicians among others. Middle Assyrian Empire kings extended Assyrian domination from Mount Ararat in the north to Dilmun (modern Bahrain) in the south, and from the Eastern Mediterranean and Antioch in the west to the Zagros (in modern northern Iran) in the east.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC) was the largest the world had yet seen; in the north, it extended to the Transcaucasia (modern Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan), to the south it encompassed Egypt, northern Nubia (modern Sudan), Libya and much of the Arabian peninsula, to the west it extended into parts of Ancient Greece, Cyprus, Cilicia, Phoenicia western Anatolia etc., and the East Mediterranean, and to the east into Persia, Media, Gutium, Parthia, Elam, Cissia and Mannea (the modern western half of Iran).[4] In 626 BC it descended into a bitter series of civil wars conducted by rival claimants to the throne, weakening it severely, and allowing it to be eventually conquered by a coalition of former subject peoples. In 615 BC combined attacks by an alliance of its former subjects; namely the Medes, Babylonians, Persians, Chaldeans, Scythians, Sagartians and Cimmerians, gradually led to its fall by 599 BC. However, Assyria was to survive as a geo-political entity until the mid 7th century AD. The Assyrians today speak dialects of Eastern Aramaic, which still contain an Akkadian grammatical structure and hundreds of Akkadian loanwords. This language was originally introduced to Assyria as the lingua franca of the Neo Assyrian Empire in the mid 8th century BC by Tiglath-pileser III.

Post Assyrian Empire

After the defeat of Ashur-uballit II in 608 BC at Haran, at Carchemish in 605 BC, and after the last center of Assyrian imperial records at Dūr-Katlimmu in 599 BC, the Assyrian empire was divided up by the key invading forces, the Babylonians and the Medes, with the Medes ruling Assyria proper. The Assyrian people, after the fall of their empire, fell under foreign domination ever since. Assyria came under the rule of the short-lived Median Empire until 546 BC. The last king of Babylon, Nabonidus (together with his son and co-regent Belshazzar), was ironically an Assyrian from Harran. Assyria then became an Achaemenid province named Athura (Assyria).[5]

The Median Empire was then conquered by Cyrus in 547 BC,[6] under the Achaemenid dynasty, and the Persian Empire was thus founded, which consumed the entire Neo-Babylonian or "Chaldean" Empire in 539 BC.[7] King Cyrus changed Assyria's capital from Nineveh to Arbela. Assyrians became front line soldiers for the Persian empire under King Xerxes, playing a major role in the Battle of Marathon under King Darius I in 490 BC.[8] Cyrus II returned the sacred images of the Assyrians to Nineveh and Assur, established for them permanent sanctuaries, gathered all their former inhabitants and returned them to their habitations. At the news of the assassination of Bardiya (son of Cyrus II), and this connection, Darius the Great declared that several satrapies including the Assyrian satrapy revolted.[7] In 482 BC, Babylonia and Assyria were joined together in the same administrative division.[7]

The Assyrian people were Christianized in the 1st to 3rd centuries,[9] in Roman Syria and Roman Assyria.[5] They were divided by the Nestorian Schism in the 5th century, and from the 8th century, they became a religious minority following the Islamic conquest of Mesopotamia. They suffered a genocide at the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, and today to a significant extent live in diaspora.

Early Christian period

In Assyrian Church of the East tradition, the Assyrians are descended from Abraham's grandson (Dedan son of Jokshan), progenitor of the ancient Assyrians.[10] Along with the Arameans, Phoenicians, Armenians, Greeks and Nabateans, they were among the first people to convert to Christianity and spread Eastern Christianity to the Far East.

The Council of Seleucia of c. 325 dealt with jurisdictional conflicts among the leading bishops. At the subsequent Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon of 410, the Christian communities of Mesopotamia renounced all subjection to Antioch and the "Western" bishops and the Bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon assumed the rank of Catholicos.

The Nestorian and Monophysite schisms of the 5th century divided the church into separate denominations. With the rise of Syriac Christianity, eastern Aramaic enjoyed a renaissance as a classical language in the 2nd to 8th centuries, and the modern Assyrian people continue to speak eastern Neo-Aramaic dialects which still retain a number of Akkadian loan words to this day.

Whereas Latin and Greek Christian cultures became protected by the Roman and Byzantine empires respectively, Assyrian/Syriac Christianity often found itself marginalized and persecuted. Antioch was the political capital of this culture, and was the seat of the patriarchs of the church. However, Antioch was heavily Hellenized, and the cities of Edessa, Nisibis, Arbela and Ctesiphon became Syriac cultural centres.

The Seleucid Greek hegemony

At the end of the Achaemenid Persian rule in 330 BC, Mesopotamia was partitioned into the satrapy of Babylon in the south, while the northern part of Mesopotamia was joined with Syria in another satrapy. It is not known how long this division lasted, but by the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, the north was removed from Syria and made into a separate satrapy. Generally speaking, the Seleucid rulers respected the native priesthood of Mesopotamia, and there is no record of persecutions.[7] There is proof that the Parthians, when establishing their sovereignty over different parts in the empire, retained the dynasts that had become independent or had been acting on behalf of the Seleucids, as long as they accepted Parthian sovereignty. Full overlordship of the Parthians was established since the full establishment of the empire under Arsaces I of Parthia. Aramaic was the official language of the Achaemenid Persian Empire; after the conquests of Alexander the Great, Greek replaced Aramaic, including up to the Seleucid empire. However, both Greek and Aramaic were used throughout the empire, although Greek was the principal language of the government. Aramaic changed different parts of the empire, and in Mesopotamia, under the subsequent rule of the Parthians it evolved into Syriac.[7]

Roman Empire

Syria became a Roman province in 64 BC, following the Third Mithridatic War. The Assyria-based army accounted for three legions of the Roman army, defending the Parthian border. In the 1st century, it was the Assyria-based army that enabled Vespasian's coup. Syria was of crucial strategic importance during the crisis of the third century. From the later 2nd century, the Roman senate included several notable Assyrians, including Claudius Pompeianus and Avidius Cassius. In the 3rd century, Assyrians even reached for imperial power, with the Severan dynasty.

From the 1st century BC, Assyria was the theatre of the protracted Perso-Roman Wars. It would become a Roman province (Assyria Provincia) between 116 and 363 AD, although Roman control of this province was unstable and was often returned to the Parthians and Persians.

Parthian hegemony

When the Seleucids passed, it was the Iranian Parthians who took their place, wielding the scepter over much of West Asia for some 400 years.[11] It is during the Parthian period that the Christianisation of Adiabene began. Despite the influx of foreign elements, despite the changes in architecture, the presence of Assyrians is confirmed by the worship of God Ashur, all proof of the continuity of the Assyrians.[7] The conclusion to be drawn from this is that the Greeks, Parthians, and Romans had a rather low-level of integration with the local population in Mesopotamia, which allowed their cultures to survive. Therefore, the large influx of Greek and Iranian Parthian elements did not wipe out the local population and culture.

The Parthians exercised only loose control over Assyria, and it saw a major cultural revival, with Ashur once more becoming independent, and other Assyrian states arising, such as Adiabene, Osroene, Beth Nuhadra and Beth Garmai, together with the partly Assyrian state of Hatra.

At the dawn of Christianity in the 1st century AD the people living in Assyria were Assyrians, bordered by Parthians, Persians, Greeks, and Armenians.[11]

Sassanid Persian hegemony

In 225 AD Parthian rule over the Assyrian territories straightly moved to the newly established and vibrant Sassanid Persian Empire.[12]

The population of Asorestan was a mixed one, composed of Assyrians, Arameans (in the far south, and western deserts), and Persians.[13][14] The Greek element in the cities, still strong in the Parthian period, was absorbed by the Semites in Sasanian times.[13] The majority of the population were Assyrian people, speaking Eastern Aramaic dialects. As the breadbasket of the Sasanian Empire, most of the population were engaged in agriculture or worked as traders and merchants. The Persians were found in the administrative class of society, as army officers, civil servants, and feudal lords, living partly in the country, partly in Ctesiphon.[13] At least three dialects of Eastern Aramaic were in spoken and liturgical use: Syriac mainly in the north and among Assyrian Christians, Mandaic in the south and among Mandaeans, and a dialect in the central region, of which the Judaic subvariety is known as Jewish Babylonian Aramaic. Aside from the liturgical scriptures of these religions which exist today, archaeological examples of all three of these dialects can be found in the collections of thousands of Aramaic incantation bowls—ceramic artifacts dated to this era—discovered in Iraq. While the Jewish Aramaic script retained the original "square" or "block" form of the Aramaic alphabet used in Imperial Aramaic (the Ashuri alphabet), the Syriac alphabet and the Mandaic alphabet developed when cursive styles of Aramaic began to appear. The Mandaic script itself developed from the Parthian chancellery script.

The religious demography of Mesopotamia was very diverse during Late Antiquity. From the 1st and 2nd centuries Syriac Christianity became the primary religion, while other groups practiced Mandaeism, Judaism, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, and the old Mesopotamian religion. Christians were probably the most numerous group in the province. The Sasanian state religion, Zoroastrianism, was largely confined to the Persian administrative class.[15] Asorestan, and particularly Assyria proper, were the centers for the Church of the East (continuity with which is now claimed by several churches), which at times (partially due to the vast areas the Sasanian empire covered) was the most widespread Christian church in the world, reaching well into Central Asia, China and India. The Church of the East went through major consolidation and expansion in 410 during the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, held at the Sasanian capital (in Asorestan). Selucia-Ctesiphon remained a location of the Patriarchate of the Church of the East for over 600 years.

This period of Sassanid hegemony lasted till the advent of the invading Rashidun Arabs between 633 and 638 AD after which Assuristan got annexed by the Islamic Arabs. Together with Mayshan became the province of al-'Irāq. A century later, the area became the capital province of the Abbasid Caliphate and the center of Islamic civilization for five hundred years; from the 8th to the 13th centuries.

Islamic empires

After the Arab Islamic Conquest of the mid 7th century AD Assuristan (Assyria) was dissolved as an entity. The Arab culture and language greatly influence the Assyrian minorities at this point the Assyrians were only a religious sect and a mixture of all middle eastern ethnicities also many of them had Greek or roman blood due to previous occupations.

Assyrian Christians especially Nestorian were highly inflonced by the Arab Civilization during the Ummayads and the Abbasids they played role by translating works of Greek philosophers to Syriac and (many of them spoke Greek) afterwards to Arabic.[16] They also excelled in philosophy, science (such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq, Qusta ibn Luqa, Masawaiyh, Patriarch Eutychius, Jabril ibn Bukhtishu etc.) and theology (such as Tatian, Bar Daisan, Babai the Great, Nestorius, Toma bar Yacoub etc.) [17][18]

However, despite this, Assyrians became second class citizens in a greater Arab Islamic state, and those who resisted conversion to Islam were subject to religious, ethnic and cultural discrimination, and had certain restrictions imposed upon them.[19] They were excluded from specific duties and occupations reserved for Muslims, did not enjoy the same political rights as Muslims, their word was not equal to that of a Muslim in legal and civil matters, as Christians they were subject to payment of a special tax (jizyah), they were banned from spreading their religion further in Muslim ruled lands, men were banned from marrying Muslim women, but at the same time they were also expected to adhere to the same laws of property, contract and obligation as the Muslim Arabs.[20] The ancient Assyrian capital of Nineveh had its bishop of the Church of the East at the time of the Arab conquest of Mesopotamia. The Arabs still recognised Assyrian identity in the Medieval period, describing them as Ashuriyun.[21]

Assyrian people, still retaining Akkadian infused and influenced Eastern Aramaic and Church of the East Christianity, remained dominant in the north of Mesopotamia (what had been Assyria) as late as the 14th century AD[22] and the city of Assur was still occupied by Assyrians during the Islamic period until the mid-14th century when the Muslim Turco-Mongol ruler Tamurlane conducted a religiously-motivated massacre of indigenous Assyrian Christians. After that, there are no traces of a settlement at Ashur in the archaeological and numismatic record, and from this point, the Assyrian population was dramatically reduced in their homeland.[23] However, another theory posits that the migration of many Assyrians out of Ashur began in the fourteenth century during the Mongol conquests.[1]

In 1552, a schism occurred within the Church of the East: the established "Eliya line" of patriarchs was opposed by a rival patriarch, Sulaqa, who initiated what is called the "Shimun line". He and his early successors entered into communion with the Catholic Church, but in the course of over a century their link with Rome grew weak and was openly renounced in 1672, when Shimun XIII Dinkha adopted a profession of faith that contradicted that of Rome, while he maintained his independence from the "Eliya line". Leadership of those who wished to be in communion with Rome passed to the Archbishop of Amid Joseph I, recognized first by the Turkish civil authorities (1677) and then by Rome itself (1681). A century and a half later, in 1830, headship of the Catholics was conferred on Yohannan Hormizd. Yohannan was a member of the "Eliya line" family, but he opposed the last of that line to be elected in the normal way as patriarch, Ishoʿyahb (1778–1804), most of whose followers he won over to communion with Rome, after he himself was irregularly elected in 1780, as Sulaqa was in 1552. The "Shimun line" that in 1553 entered communion with Rome and broke it off in 1672 is now that of the church that in 1976 officially adopted the name "Assyrian Church of the East",[24][25][26][27] while a member of the "Eliya line" family is one of the patriarchs of the Chaldean Catholic Church.

For many centuries, from at least the time of Jerome (c. 347 – 420),[28] the term "Chaldean" indicated the Aramaic language and was still the normal name in the nineteenth century.[29][30][31] Only in 1445 did it begin to be used to mean Aramaic speakers in communion with the Catholic Church, on the basis of a decree of the Council of Florence,[32] which accepted the profession of faith that Timothy, metropolitan of the Aramaic speakers in Cyprus, made in Aramaic, and which decreed that "nobody shall in future dare to call [...] Chaldeans, Nestorians".[33][34][35] Previously, when there were as yet no Catholic Aramaic speakers of Mesopotamian origin, the term "Chaldean" was applied with explicit reference to their "Nestorian" religion. Thus Jacques de Vitry wrote of them in 1220/1 that "they denied that Mary was the Mother of God and claimed that Christ existed in two persons. They consecrated leavened bread and used the 'Chaldean' (Syriac) language".[36] Until the second half of the 19th century. the term "Chaldean" continued in general use for East Syriac Christians, whether "Nestorian" or Catholic:[37][38][39][40] it was the West Syriacs who were reported as claiming descent from Asshur, the second son of Shem.[41]

Starting from the 19th century after the rise of nationalism in the Balkans, the Ottomans started viewing Assyrians and other Christians in their eastern front as a potential threat. Furthermore, constant wars between The Ottomans and the Shiite Safavids encouraged the Ottomans into settling their allies, the nomadic Sunni Kurds, in what is today Northern Iraq and South-eastern Turkey.[42] Starting from then, Kurdish tribal chiefs established semi-independent emirates. The Kurdish Emirs sought to consolidate their power by attacking Assyrian communities which were already well established there. Scholars estimate that tens of thousands of Assyrian in the Hakkari region were massacred in 1843 when Badr Khan the emir of Bohtan invaded their region.[43] After a later massacre in 1846 The Ottomans were forced by the western powers into intervening in the region, and the ensuing conflict destroyed the Kurdish emirates and reasserted the Ottoman power in the area. The Assyrians of Amid were also subject to the massacres of 1895.

20th century

The Assyrians suffered a further catastrophic series of massacres known as the Assyrian Genocide, at the hands of the Ottomans and their Kurdish and Arab allies from 1915–1918. The genocide (committed in conjunction with the Armenian Genocide and Greek Genocide) accounted for up to 750,000 unarmed Assyrian civilians and the forced deportations of many more. The sizable Assyrian presence in southeastern Asia Minor which had endured for over four millennia was reduced to a few thousand. As a consequence, the surviving Assyrians took up arms, and an Assyrian war of independence was fought during World War I, For a time, the Assyrians fought successfully against overwhelming numbers, scoring a number of victories over the Ottomans and Kurds, and also hostile Arab and Iranian groups; then their Russian allies left the war following the Russian Revolution, and Armenian resistance broke. The Assyrians were left cut off, surrounded, and without supplies, forcing those in Asia Minor and Northwest Iran to fight their way, with civilians in tow, to the safety of British lines and their fellow Assyrians in the Assyrian homeland of northern Iraq. Assyrians prominently served in Iraq Levies organized by the British in 1919, and after 1928, these became the Assyrian Levies.

Many Assyrians from Hakkari settled in Syria after they were displaced and driven out by Ottoman Turks in southeast Turkey in the early 20th century.[44] During the 1930s and 1940s, many Assyrians resettled in northeastern Syrian villages, such as Tel Tamer, Al-Qahtaniyah Al Darbasiyah, Al-Malikiyah, Qamishli and a few other small towns in Al-Hasakah Governorate.[45]

In 1932, Assyrians refused to become part of the newly formed state of Iraq and instead demanded their recognition as a nation within a nation. The Assyrian leader Mar Shimun XXI Eshai asked the League of Nations to recognize the right of Assyrians to govern the area known as the "Assyrian triangle" in northern Iraq. The Assyrians suffered the Simele Massacre, where thousands of unarmed villagers (men, women, and children) were slaughtered by joint Arab-Kurdish forces of the Iraqi Army. These massacres followed a clash between Assyrian tribesmen and the Iraqi army, where the Iraqi forces suffered a defeat after trying to disarm the Assyrians, whom they feared would attempt to secede from Iraq. Armed Assyrian Levies were prevented by the British from going to the aid of these defenseless civilians.[46] Eventually this led to the Iraqi government to commit its first of many massacres against its unarmed minority populations (see Simele massacre).[47]

The Assyrian Levies were founded by the British in 1928, with ancient Assyrian military rankings, such as Rab-shakeh, Rab-talia and Tartan, being revived for the first time in millennia for this force. The Assyrians were prized by the British rulers for their fighting qualities, loyalty, bravery and discipline, and were used to help the British put down insurrections among the Arabs and Kurds, guard the borders with Iran and Turkey and protect British military installations.[48]

The Assyrians were allied with the British during World War II, with eleven Assyrian companies seeing action in Palestine/Israel and another four serving in Cyprus. The Parachute Company was attached to the Royal Marine Commando and Assyrian Paratroopers were involved in fighting in Albania, Italy and Greece. Assyrians played a major role in the victory over Arab-Iraqi forces at the Battle of Habbaniya and Anglo-Iraq war in 1941, when the Iraqi government decided to join WW2 on the side of Nazi Germany. The British presence in Iraq lasted until 1954, and Assyrian Levies remained attached to British forces until this time.

The period from the 1940s through to 1963 saw a period of respite for the Assyrians. The regime of President Kassim, in particular, saw the Assyrians accepted into mainstream society. Many urban Assyrians became successful businessmen, others were well represented in politics and the military, their towns and villages flourished undisturbed, and Assyrians came to excel, and be over-represented in sports such as Boxing, Football, Athletics, Wrestling and Swimming.

However, in 1963, the Ba'ath Party took power by force in Iraq. The Baathists, though secular, were Arab Nationalists, and set about attempting to Arabize the many on Arab peoples of Iraq, including the Assyrians. Other ethnic groups targeted for forced Arabization included Kurds, Armenians, Turcomans, Mandeans, Yezidi, Shabaki, Kawliya, Persians and Circassians. This policy included refusing to acknowledge the Assyrians as an ethnic group, banning the publication of written material in Eastern Aramaic, and banning its teaching in schools, banning parents giving Assyrian names to their children, banning Assyrian political parties, taking control of Assyrian churches, attempting to divide Assyrians on denominational lines (e.g. Assyrian Church of the East vs Chaldean Catholic Church vs Syriac Orthodox) and forced relocations of Assyrians from their traditional homelands to major cities.

In response to Baathist persecution, the Assyrians of the Zowaa movement within the Assyrian Democratic Movement took up armed struggle against the Iraqi regime in 1982 under the leadership of Yonadam Kanna,[49] and then joined up with the IKF in the early 1990s. Yonadam Kanna, in particular, was a target of the Saddam Hussein Ba'ath regime for many years.

The policies of the Baathists have also long been mirrored in Turkey, whose governments have refused to acknowledge the Assyrians as an ethnic group since the 1920s, and have attempted to Turkify the Assyrians by calling them Semitic Turks and forcing them to adopt Turkic names. In Syria too, the Assyrian/Syriac Christians have faced pressure to identify as Arab Christians.

Many persecutions have befallen the Assyrians since, such as the Anfal campaign and Baathist, Arab and Kurdish nationalist and Islamist persecutions.

Post-Ba'thist Iraq

With the fall of Saddam Hussein and the 2003 invasion of Iraq, no reliable census figures exist on the Assyrians in Iraq (as they do not for Iraqi Kurds or Turkmen), though the number of Assyrians is estimated to be approximately 800,000.

The Assyrian Democratic Movement (or ADM) was one of the smaller political parties that emerged in the social chaos of the occupation. Its officials say that while members of the ADM also took part in the liberation of the key oil cities of Kirkuk and Mosul in the north, the Assyrians were not invited to join the steering committee that was charged with defining Iraq's future. The ethnic make-up of the Iraq Interim Governing Council briefly (September 2003 – June 2004) guided Iraq after the invasion included a single Assyrian Christian, Younadem Kana, a leader of the Assyrian Democratic Movement and an opponent of Saddam Hussein since 1979.

In October 2008 many Iraqi Christians(about 12,000 almost Assyrians) have fled the city of Mosul following a wave of murders and threats targeting their community. The murder of at least a dozen Christians, death threats to others, the destruction of houses forced the Christians to leave their city in hurry. Some families crossed the borders to Syria and Turkey while others have been given shelters in Churches and Monasteries. Accusations and blames have been exchanged between Sunni fundamentalists and some Kurdish groups for being behind this new exodus. For the time the motivation of these culprits remains mysterious, but some claims related it to the provincial elections due to be held at the end of January 2009, and especially connected to Christian's demand for wider presentation in the provincial councils.[50]

In recent years, the Assyrians in northern Iraq and northeast Syria have become the target of extreme unprovoked Islamic terrorism. As a result, Assyrians have taken up arms, alongside other groups (such as the Kurds, Turcomans and Armenians) in response to unprovoked attacks by Al Qaeda, ISIS/ISIL, Nusra Front and other terrorist Islamic Fundamentalist groups. In 2014 Islamic terrorists of ISIS attacked Assyrian towns and villages in the Assyrian Homeland of northern Iraq, together with cities such as Mosul and Kirkuk which have large Assyrian populations. There have been reports of atrocities committed by ISIS terrorists since, including; beheadings, crucifixions, child murders, rape, forced conversions, Ethnic Cleansing, robbery, and extortion in the form of illegal taxes levied upon non-Muslims. Assyrians in Iraq have responded by forming armed Assyrian militias to defend their territories.

Assyrian continuity

Thus far, the only people who have been attested with a high level of genetic, historical, linguistic and cultural research to be the descendants of the ancient Mesopotamians are the Assyrian Christians of Iraq and its surrounding areas in northwest Iran, northeast Syria and southeastern Turkey (see Assyrian continuity), although others have made unsubstantiated claims of continuity. Assyria continued to exist as a geopolitical entity until the Arab-Islamic conquest in the mid-7th century, and Assyrian identity, personal, family and tribal names, and both spoken and written evolutions of Mesopotamian Aramaic (which still contain many Akkadian loan words and an Akkadian grammatical structure) have survived among the Assyrian people from ancient times to this day (see Assyrian people).

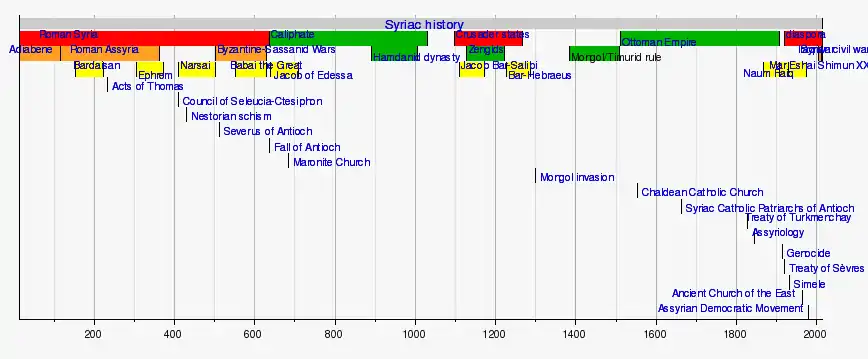

Timeline

See also

- Assyrian continuity

- Assyrian people

- Assyria

- Old Assyrian Empire

- Middle Assyrian Empire

- Neo Assyrian Empire

- Akkadian Empire

- Sumer

- Achaemenid Assyria

- Athura

- Seleucid Syria

- Roman Province of Assyria

- Assuristan

- Adiabene

- Osroene

- Assur

- Beth Nuhadra

- Beth Garmai

- Hatra

- Babylonia

- Chaldea

- Assyrian homeland

- List of Assyrians

- Assyrian struggle for independence

- Archaeogenetics of the Near East

- Assyrian nationalism

- Syriac language

- Name of Syria

- Eastern Aramaic languages

- Syriac language

- Names of Syriac Christians

- History of Syriac Christianity

- Assyrian Genocide

- Assyrian diaspora

- Assyrian culture

- Assyrian cuisine

- Assyrian music

- Assyrian levies

- Mesopotamian Religion

- Assyrian Church of the East

- Syriac Orthodox Church

- Nestorian Church

- Chaldean Catholic Church

- Assyrian Pentecostal Church

- Ancient Church of the East

- Assyrian Evangelical Church

External links

References

- Carl Skutsch (2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-135-19388-1.

- Deutscher, Guy (2007). Syntactic Change in Akkadian: The Evolution of Sentential Complementation. Oxford University Press US. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-19-953222-3.

- Woods C. 2006 "Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian". In S. L. Sanders (ed) Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture: 91–120 Chicago

- "Assyrian Eponym List". Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- Frye, Richard N. (1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms" (PhD., Harvard University). Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 51 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1086/373570. S2CID 161323237.

The ancient Greek historian, Herodotus, wrote that the Greeks called the Assyrians, by the name Syrian, dropping the A and first S. And that's the first instance we know of, of the distinction in the name, of the same people. Then the Romans, when they conquered the western part of the former Assyrian Empire, they gave the name Syria, to the province, they created, which is today Damascus and Aleppo. So, that is the distinction between Syria, and Assyria. They are the same people, of course. And the ancient Assyrian empire, was the first real, empire in history. What do I mean, it had many different peoples included in the empire, all speaking Aramaic, and becoming what may be called, "Assyrian citizens." That was the first time in history, that we have this. For example, Elamite musicians, were brought to Nineveh, and they were 'made Assyrians' which means, that Assyria, was more than a small country, it was the empire, the whole Fertile Crescent.

- Olmatead, History of the Persian Empire, Chicago University Press, 1959, p.39

- Yana, George V. (10 April 2008). Ancient and Modern Assyrians: A Scientific Analysis. ISBN 9781465316295. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- Artifacts show rivals Athens and Sparta, Yahoo News, December 5, 2006.

- Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. JAAS. 18 (2): 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17.

From the 3rd century AD on, the Assyrians embraced Christianity in increasing numbers

- Genesis 25:3

- Wigram, W. A. (2002). The Assyrians and Their Neighbors. ISBN 9781931956116. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- Wigram, W. A. (2002). The Assyrians and Their Neighbors. ISBN 9781931956116. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- "ĀSŌRISTĀN". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

ĀSŌRISTĀN, name of the Sasanian province of Babylonia.

- Buck, Christopher (1999). Paradise and Paradigm: Key Symbols in Persian Christianity and the Baháí̕ Faith. SUNY Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780791497944.

- Etheredge, Laura (2011). Iraq. Rosen Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 9781615303045.

- Hill, Donald. Islamic Science and Engineering. 1993. Edinburgh Univ. Press. ISBN 0-7486-0455-3, p.4

- Rémi Brague, Assyrians contributions to the Islamic civilization

- Britannica, Nestorian

- Clinton Bennett (2005). Muslims and Modernity: An Introduction to the Issues and Debates. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 163. ISBN 082645481X. Retrieved 2012-07-07

- H. Patrick Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World. Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 219.

- Hannibal Travis Archived 2012-05-23 at Archive.today (2006), "Native Christians Massacred": The Ottoman Genocide of the Assyrians During World War I, Genocide Studies and Prevention, vol. 1.3, pp. 329

- According to Georges Roux and Simo Parpola

- "History of Ashur". Assur.de. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (8 December 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2.

- Eckart Frahm (24 March 2017). A Companion to Assyria. Wiley. p. 1132. ISBN 978-1-118-32523-0.

- Joseph, John (July 3, 2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: A History of Their Encounter with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers. BRILL. ISBN 9004116419 – via Google Books.

- "Fred Aprim, "Assyria and Assyrians Since the 2003 US Occupation of Iraq"" (PDF). Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- Edmon Louis Gallagher (23 March 2012). Hebrew Scripture in Patristic Biblical Theory: Canon, Language, Text. BRILL. pp. 123, 124, 126, 127, 139. ISBN 978-90-04-22802-3.

- Julius Fürst (1867). A Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament: With an Introduction Giving a Short History of Hebrew Lexicography. Tauchnitz.

- Wilhelm Gesenius; Samuel Prideaux Tregelles (1859). Gesenius's Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament Scriptures. Bagster.

- Benjamin Davies (1876). A Compendious and Complete Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament, Chiefly Founded on the Works of Gesenius and Fürst ... A. Cohn.

- Coakley, J. F. (2011). Brock, Sebastian P.; Butts, Aaron M.; Kiraz, George A.; van Rompay, Lucas (eds.). Chaldeans. Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-59333-714-8.

- "Council of Basel-Ferrara-Florence, 1431-49 A.D.

- Braun-Winkler, p. 112

- Michael Angold; Frances Margaret Young; K. Scott Bowie (17 August 2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 5, Eastern Christianity. Cambridge University Press. p. 527. ISBN 978-0-521-81113-2.

- Wilhelm Braun, Dietmar W. Winkler, The Church of the East: A Concise History (RoutledgeCurzon 2003), p. 83

- Ainsworth, William (1841). "An Account of a Visit to the Chaldeans, Inhabiting Central Kurdistán; and of an Ascent of the Peak of Rowándiz (Ṭúr Sheïkhíwá) in Summer in 1840". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 11. e.g. p. 36. doi:10.2307/1797632. JSTOR 1797632.

- William F. Ainsworth, Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Chaldea and Armenia (London 1842), vol. II, p. 272, cited in John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East (BRILL 2000), pp. 2 and 4

- Layard, Austen Henry (July 3, 1850). Nineveh and its remains: an enquiry into the manners and arts of the ancient assyrians. Murray. p. 260 – via Internet Archive.

Chaldaeans Nestorians.

- Simon (oratorien), Richard (July 3, 1684). "Histoire critique de la creance et des coûtumes des nations du Levant". Chez Frederic Arnaud – via Google Books.

- Southgate, Horatio (July 3, 1844). Narrative of a Visit to the Syrian [Jacobite] Church of Mesopotamia. D. Appleton. p. 141 – via Internet Archive.

southgate papal chaldean.

- Hirmis Aboona, Assyrians, Kurds, and Ottomans: Intercommunal Relations on the Periphery of the Ottoman Empire, pp. 105

- David Gaunt, Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern, pp. 32

- Betts, Robert Brenton, Christians in the Arab East (Atlanta, 1978)

- Dodge, Bayard, "The Settlement of the Assyrians on the Khabur," Royal Central Asian Society Journal, July 1940, pp. 301-320.

- Ye'or, Bat; Miriam Kochan; David Littman (2002). Islam, and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 148. ISBN 0-8386-3943-7. OCLC 47054791.

- Iraq Between the Two World Wars: The Militarist Origins of Tyranny, by Reeva Spector Simon

- Len Deighton (1993), Blood, Tears and Folly

- "زوعا". www.zowaa.org. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- "Iraqi Christians' fear of exile". BBC. 2008-10-28. Retrieved 2016-09-10.