History of the Cape Colony from 1870 to 1899

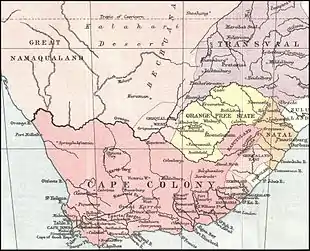

The year 1870 in the history of the Cape Colony marks the dawn of a new era in South Africa, and it can be said that the development of modern South Africa began on that date. Despite political complications that arose from time to time, progress in Cape Colony continued at a steady pace until the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer Wars in 1899. The discovery of diamonds in the Orange River in 1867 was immediately followed by similar finds in the Vaal River. This led to the rapid occupation and development of huge tracts of the country, which had hitherto been sparsely inhabited. Dutoitspan and Bultfontein diamond mines were discovered in 1870, and in 1871 the even richer mines of Kimberley and De Beers were discovered. These four great deposits of mineral wealth were incredibly productive, and constituted the greatest industrial asset that the Colony possessed.

| Part of a series on |

| Cape Colony history |

|---|

This period also witnessed the increasing tensions between the English-dominated Cape Colony and the Afrikaner-dominated Transvaal. These conflicts led to the outbreak of the First Boer War. These tensions mainly concerned the easing of trade restrictions between the different colonies, as well as the construction of railways.

Socio-economic Background

At the time of the beginning of the diamond industry, all of South Africa was experiencing depressed economic conditions. Ostrich-farming was in its infancy, and agriculture had only been lightly developed. The Boers, except those in the immediate vicinity of Cape Town, lived in impoverished conditions. They only traded marginally with the Colony for durable goods. Even the British colonists were far from wealthy. The diamond industry was therefore considerably attractive, especially to colonists of British origin. It was also a means to demonstrate that South Africa, which appeared to be barren and poor on the surface, was rich below the ground. It takes 10 acres (40,000 m2) of Karoo to feed a sheep, but it was now possible that a few square metres of diamondiferous blue ground would be able to feed a dozen families. By the end of 1871, a large population had already gathered on the diamond fields, and immigration increased dramatically, which brought in many newcomers. Among the first to seek a fortune on the diamond fields was Cecil Rhodes.

The Beginning of Responsible Government

The Cape Colony was brought under "responsible government" in 1872. Under its previous political system, the government ministers of the Cape reported to the appointed British Governor of Cape Colony, and not to the locally elected Cape Parliament. A popular movement arose in the early 1860s, led by local leader John Molteno, to make the government of the country accountable (or "responsible") to parliament and the local electorate, thereby gaining a degree of independence from Britain. Throughout most of the 1860s, the Cape was dominated by a political struggle between the British Governor and the growing responsible government movement. The political deadlock was accompanied by economic stagnation and bitter regional divisions between the Cape's provinces.[1][2]

Finally in 1872, Molteno – with the backing of a new Governor Henry Barkly – instituted responsible government, making ministers responsible to Parliament, and becoming the Cape's first Prime Minister. The ensuing years saw a rapid surge in economic growth, a country-wide expansion of infrastructure as well as a period of regional integration and social development. Though the Confederation wars were soon to interrupt this new stability, the Cape remained under responsible government for the remainder of its history, until it became the Cape Province within the new Union of South Africa in 1910. An important point to be made about the political system of the Cape under responsible government, was that it was the only state of southern Africa to have a non-racial system of voting. In the following century however – after the Act of Union of 1910 to form the Union of South Africa – this multi-racial universal suffrage was steadily eroded, and eventually abolished by the Apartheid government in 1948. [3][4]

Failed Attempt at Confederation

The idea of melding the states of southern Africa into a Confederation was not new. An earlier plan by Sir George Grey for a federation of all the various colonies in South Africa had been rejected by the home authorities in 1858 as not being viable. Later, the 4th Earl of Carnarvon, secretary of state for the colonies, having successfully federated Canada, drew up a new plan to impose the same system of confederation on the (very different) states of Southern Africa. Southern Africa, seen as vital for the security of the Empire, was only partially under British control at the time. Black African and Boer states remained uncolonised, and the Cape Colony had just attained a degree of independence.[5]

Confederating the various states under British rule was seen as the best way of establishing overall British control with the minimum blood-shed, and ending the autonomy of the remaining independent states.[6] The imposition of a federation upon Southern Africa was, however, doomed to failure and led to resentment across the region (culminating disastrously in the Anglo-Zulu War, the First Boer War and other conflicts).

The Cape Colony's response

There was little local enthusiasm for the confederation project. Prominent Cape politicians, while acknowledging the success of the Confederation model in Canada, questioned its suitability for Southern Africa. They also criticised the timing of the scheme as particularly unfortunate – coming when the different states of Southern Africa were still unstable and simmering after the last bout of British imperial expansion. The Cape Prime Minister John Molteno correctly warned that the imposition of a lop-sided confederation would cause instability and resentment. He advised full union as a better model for Southern Africa – but only at a later date, once it was economically viable and tensions had died down.

Direct British rule in the Cape Colony had recently been replaced by responsible government, and the newly elected Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope in Cape Town, under the liberal Molteno-Merriman government, resented the perceived high-handed manner in which Lord Carnarvon presented his proposals from afar without an understanding of local affairs. It also suspected him of manoeuvring to consolidate British control over the region's states, reverse the Cape's independence, and bring on a war with the neighbouring Xhosa Chiefs. Molteno's government raised the additional concern, transmitted to London by Sir Henry Barkly, that any federation with the illiberal Boer republics would endanger the rights and franchise of the Cape's black citizens; if there was to be any form of union, the Cape's non-racialism would need to be implemented in the Boer republics, and could not be compromised.[7] A resolution was passed in the Cape Parliament on 11 June 1875, stating that any scheme in favour of confederation must originate locally, from among southern African states, and not be imposed by London.

Lord Carnarvon responded by sending the distinguished historian James Anthony Froude to Southern Africa, with orders to push discreetly for confederation, test popular opinion about it and report all information directly back to Carnarvon. However, the general public in South Africa saw him as a representative of the British government and local suspicion of his agenda ensured that his trip was not a success; in fact he entirely failed to induce Southern Africans to adopt Lord Carnarvon's confederation system.

The Molteno Unification Plan (1877), put forward by the Cape government as a more feasible unitary alternative to confederation, largely anticipated the final act of Union in 1909. A crucial difference was that the Cape's constitution and multiracial franchise were to be extended to the other states of the union. These smaller states would gradually accede to the much larger Cape Colony through a system of treaties, whilst gaining elected seats in the Cape parliament. The entire process would be locally driven, with Britain's role restricted to policing any set backs. While subsequently acknowledged to be more viable, this model was rejected at the time by London.[8]

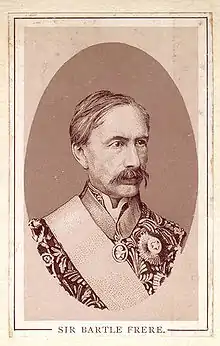

Lord Carnarvon, still bent on imposing confederation on Southern Africa, now appointed his political ally Sir Bartle Frere as governor of Cape Colony and high commissioner of South Africa. Frere was appointed on the understanding that he would work to enforce Carnarvon's confederation plan and, in return, he could then become the first British governor of a united southern African confederation.

Serious African insurrections began soon afterwards, in Zululand and on the Xhosa frontier of the Cape Colony. In 1876, the British had annexed Fingoland, the Idutywa reserve and other Xhosa lands, on the understanding that the Cape government should take them over and provide for their government, however there was a serious rebellion by the amaGcaleka and the amaNgqika (or Gaikas) and a considerable force of imperial and colonial troops was required to put down the uprising. The war was subsequently known as the Ninth Xhosa War and the famous Xhosa chief, Sandile, lost his life during its course. After the war ended, the Transkei (the territory of the Gcaleka tribe, who were led by Sarhili “Kreli”), was annexed by the British.

Frere's dissolving of the elected Cape Government removed any constitutional obstructions to the colonial office's confederation plan, but was overshadowed by growing unrest and anti-British agitation across the whole region.

Anglo-Zulu and Anglo-Boer Wars

The Transvaal had been brought under British control through a peacefully annexation from the south-east in 1877, under Sir Theophilus Shepstone. The remaining Xhosa Kingdoms had all been annexed, though upheavals continued. With the Cape government removed and a puppet Prime Minister (John Gordon Sprigg) installed, Frere turned to the Zulu Kingdom to the east, under its King, Cetshwayo. As an independent state, it needed to be brought under British control in order to be melded into the planned Confederation.

Frere impressed upon the Colonial Office his belief that Cetshwayo's army had to be eliminated, an idea that was generally accepted until Frere sent Cetshwayo a provocative and impossible ultimatum in December 1878 and the home government began to realise the problems inherent in a native war. Cetshwayo was unable to comply with Frere's ultimatum-even if he had wanted to; Frere ordered Lord Chelmsford to invade Zululand, and so the Anglo-Zulu War began. Fourteen days later the disaster of Isandlwana was reported, and the House of Commons demanded that Frere be recalled. Beaconsfield supported him, however, and in a strange compromise he was censured but allowed to stay on. The Zulu trouble, and disaffection brewing in the Transvaal, reacted upon each other most disastrously. The delay in giving the country a constitution afforded a pretext for agitation to the discontented Boers, a rapidly increasing minority, while the reverse at Isandlwana had lowered British prestige. On his return to Cape Town, Frere found that his achievement had been eclipsed—first by 1 June 1879 death of Napoleon Eugene, Prince Imperial, in Zululand, and then by the news that the government of the Transvaal and Natal, together with the high commissionership for the south-eastern part of South Africa, had been transferred from him to Sir Garnet Wolseley. Meanwhile, Boer resentment had boiled over and full-blown rebellion broke out in the Transvaal, leading to the First Boer War(1880–1881) and the independence of the Boer republics.

While the war was being fought, Lord Carnarvon resigned his position in the British cabinet and his scheme for confederation was abandoned.

Effects of the confederation wars

Lord Carnarvon had failed to appreciate the geo-political differences between Canada and Southern Africa, and how inappropriate a Canadian-style confederation was for the Southern African political landscape. The timing of the scheme was also inauspicious, as at the time the relations between the different states of Southern Africa was still fragile after the previous wave of British imperial expansion.

A new wave of discontent spread amongst the different Xhosa tribes on the colonial frontier, and there was another uprising in Basutoland under Moirosi after the Gaika-Galeka War. The Xhosa under Moirosi were put down with severe fighting by a colonial force, but their defeat notwithstanding, the Basotho remained restless and aggressive for several years. In 1880, the British colonial authorities attempted to extend the Peace Preservation Act of 1878 to Basutoland, attempting a general disarmament of the Basotho. Further fighting followed the proclamation, which did not have a conclusive end, although peace was declared in December 1882. The imperial government took over Basutoland as a crown colony, on the understanding that Cape Colony should contribute £18,000 annually for administrative purposes. The authorities of the Colony were glad to be relieved in 1884 of the administration of Basutoland, whose administration had already cost them more than £3,000,000.

Sir Bartle Frere had been recalled in 1880 to face charges of misconduct, by the 1st Earl of Kimberley (secretary of state for the colonies). He was succeeded by Sir Hercules Robinson. Griqualand West, which included most of the diamond fields, also became an incorporated portion of Cape Colony.

A long-lasting consequence of the Confederation wars was the solidification of hostilities between the Boer and British inhabitants of southern Africa. These were later to feed into the far larger Second Boer War.[9]

Origin of the Afrikander Bond

The disastrous end of the First Anglo-Boer War of 1881 had repercussions that spread throughout South Africa. One of the most important results was the first Afrikander Bond congress that was held in 1882 at Graaff-Reinet. The Bond developed to include both the Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and Cape Colony. Each country had a provincial committee with district committees, and branches were distributed through South Africa. Later on, the Bond in the Cape Colony dissociated itself from its Republican branches. The policy of the Bond is best summarised by an excerpt from De Patriot, a paper published in the colony and an avowed supporter of the Bond.

- “The Afrikander Bond has for its object the establishment of a South African nationality by spreading a true love for what is really our fatherland. No better time could be found for establishing the Bond than the present, when the consciousness of nationality has been thoroughly aroused by the Transvaal war . . . The British government keeps on talking about a confederation under the British flag, but that will never be brought about. They can be quite certain of that. There is just one obstacle in the way of confederation, and that is the British flag. Let them remove that, and in less than a year the confederation would be established under the Free Afrikander flag.

- After a time the English will realise that the advice given them by Froude was the best – they must just have Simon's Bay as a naval and military station on the way to India, and give over all the rest of South Africa to the Afrikanders . . . Our principal weapon in the social war must be the destruction of English trade by our establishing trading companies for ourselves . . . It is the duty of each true Afrikander not to spend anything with the English that he can avoid.” (De Patriot. 1882.)

In addition to its press organs, the Bond published official statements from time to time that were less frank in their tone than the statements from its press. Some of the articles of the Bond's original manifesto can be considered entirely neutral, e.g. those referring to the administration of justice, honouring people, etc. However, these clauses were meaningless in the view of the government in Cape Colony, for Article 3 on the manifesto advocated complete independence (Zelfstandieheid) for South Africa, which was tantamount to treason against the Crown.

If the Bond prompted disloyalty and insubordination in some of the Cape inhabitants, it also caused loyalty and patriotism in another group. A pamphlet written in 1885 for an association called the Empire League on the behalf of the Bond, stated the following:

- "(1) That the establishment of the English government here was beneficial to all classes; and

- (2) that the withdrawal of that government would be disastrous to every one having vested interests in the colony. . . . England never can, never will, give up this colony, and we colonists will never give up England. Let us, the inhabitants of the Cape Colony, be swift to recognise that we are one people, cast together under a glorious flag of liberty, with heads clear enough to appreciate the freedom we enjoy, and hearts resolute to maintain our true privileges; let us desist from reproaching and insulting one another, and, rejoicing that we have this goodly land as a common heritage, remember that by united action only can we realise its grand possibilities. We belong both of us to a home-loving stock, and the peace and prosperity of every home in the land is at stake. On our action now depends the question whether our children shall curse or bless us; whether we shall live in their memory as promoters of civil strife, with all its miserable consequences, or as joint architects of a happy, prosperous, and united state. Each of us looks back to a noble past. United, we may ensure to our descendants a not unworthy future. Disunited, we can hope for nothing but stagnation, misery and ruin. Is this a light thing?"

It is probable that many Englishmen who read the Empire League's manifesto at the regarded it as unduly alarmist, but subsequent events proved the soundness of the views it expressed. From 1881 onwards, two great rival ideas came into being, each strongly opposed to the other. One was that of Imperialism — full civil rights for every "civilized" man, whatever his race might be, under the supremacy and protection of Britain. The other was nominally republican, but in fact exclusively oligarchic and Dutch. The policy of the extremists of this last party was summed up in the appeal, which President Kruger made to the Free State in February 1881, when he bade them: "Come and help us. God is with us. It is his will to unite us as a people ... to make a united South Africa free from British authority."

The two actual founders of the Bond party were a German man named Borckenhagen who lived in Bloemfontein, and an Afrikaner named Reitz, who afterwards became the state secretary of the Transvaal. There are two recorded interview that show the true aims of the founders of the Bond from the very beginning. One occurred between Borckenhagen and Cecil Rhodes, the other between Reitz and T. Schreiner, whose brother later became prime minister of Cape Colony. In the first interview, Borckenhagen remarked to Rhodes: "We want a united Africa," and Rhodes replied: "So do I". Mr Borckenhagen then continued: "There is nothing in the way; we will take you as our leader. There is only one small thing: we must, of course, be independent of the rest of the world." Rhodes replied: "You take me either for a rogue or a fool. I should be a rogue to forfeit all my history and my traditions; and I should be a fool, because I should be hated by my own countrymen and mistrusted by yours." But as Rhodes said in Cape Town in 1898, "the only chance of a true union is the overshadowing protection of a supreme power, and any German, Frenchman, or Russian would tell you that the best and most liberal power is that over which Her Majesty reigns."

The other interview took place just as the Bond was being established. Being approached by Reitz, Schreiner objected to the fact that the Bond aimed ultimately to overthrow British rule and remove the British flag from South Africa. To this, Reitz replied: "Well, what if it is so?" Schreiner expostulated in the following terms: "You do not suppose that that flag is going to disappear without a tremendous struggle and hard fighting?" "Well, I suppose not, but even so, what of that?" rejoined Reitz. In the face of this testimony with reference to two of the most prominent of the Bond's promoters, it is impossible to deny that from its beginning the great underlying idea of the Bond was an independent South Africa.

Rhodes and Dutch sentiment

Cecil Rhodes recognised the difficulties of his position and showed a desire to conciliate Dutch sentiment by considerate treatment from the outset of his political career. Rhodes was first elected as member of the House of Assembly for Barkly West in 1880 to a loyal constituency. He supported the bill permitting the use of Dutch in the House of Assembly in 1882, and, early in 1884, he was appointed to his first ministerial post as treasurer-general under Sir Thomas Scanlen. Rhodes had only held this position for six weeks when Sir Thomas Scanlen resigned. Sir Hercules Robinson sent him to British Bechuanaland in August 1884 as deputy-commissioner to succeed Reverend John Mackenzie, the London Missionary Society's representative at Kuruman, who proclaimed Queen Victoria's authority over the district in May 1883. Rhodes's efforts to conciliate the Boers failed, hence the necessity for the Warren mission. In 1885, the territories of Cape Colony were farther extended, and Tembuland, Bomvanaland, and Galekaland were formally added to the colony. Sir Gordon Sprigg became prime minister in 1886.

South African Customs Union

There was considerable unrest in Cape Colony in the period from 1878 to 1885 – sparked in part by the attempts of the British Colonial Office to impose a system of confederation on Southern Africa and to disarm all Africans in the Cape. In a short period of time, there was the Anglo-Zulu War, chronic troubles with the Basutos (which prompted the Cape to relinquish control of Basutoland to the imperial authorities) as well as a series of conflicts with the Xhosa which were followed by the First Boer War of 1881 and the Bechuanaland disturbances of 1884.

In spite of these drawbacks, the development of the country continued. The diamond industry was flourishing. A conference was held in London in 1887 for "promoting a closer union between the various parts of the British empire by means of an imperial tariff of customs". At this conference, Hofmeyr proposed a sort of "Zollverein" scheme, in which imperial customs were to be levied independently of the duties payable on all goods entering the empire from abroad. In making the proposition, he stated that his objective was "to promote the union of the empire, and at the same time to obtain revenue for the purposes of general defence". The scheme was found to be impractical at the time. But its wording, as well as the sentiments accompanying it, created a favourable view of Hofmeyr.

In spite of the disastrous failure of political confederation, the members of the Cape parliament set about establishing a South African Customs Union in 1888. A Customs Union Bill was passed and, shortly afterwards, the Orange Free State joined the union. There was the first of many attempts to get the Transvaal to join, but President Kruger, who was pursuing his own policy, hoped to make the South African Republic entirely independent of Cape Colony through the Delagoa Bay railway. The plan to create a customs union that included the Transvaal was also little to the taste of President Kruger's Hollander advisers as they were invested in the plans of the Netherlands Railway Company, who owned the railways of the Transvaal.

Diamonds and railways

Another event of considerable commercial importance to the Cape Colony, and indeed to all of South Africa, was the amalgamation of the diamond-mining companies which was chiefly brought about by Cecil Rhodes, Alfred Beit and “Barney” Barnato in 1889. One of the principal and most beneficial results of the discovery and development of the diamond mines was the great impetus that it gave to railway expansion. Lines were opened up to Worcester, Beaufort West, Grahamstown, Graaff-Reinet, and Queenstown. Kimberley was reached in 1885. In 1890 the line was extended northwards on the western frontier of the Transvaal as far as Vryburg in British Bechuanaland. In 1889, the Free State entered into an arrangement with the Cape Colony whereby the main trunk railway was extended to Bloemfontein, the Free State receiving half the profits. Subsequently, the Free State bought at cost price the portion of the railway in its own territory. In 1891, the Free State railway was still farther extended to Viljoen's Drift on the Vaal River, and in 1892 it reached Pretoria and Johannesburg.

Rhodes as Prime Minister

In 1889 Sir Henry Loch was appointed high commissioner and governor of Cape Colony after succeeding Sir Hercules Robinson. In 1890 Sir Gordon Sprigg, the premier of the colony, resigned, and a government under Rhodes was formed. Prior to the formation of this ministry, and while Sir Gordon Sprigg was still in office, Hofmeyr had approached Rhodes and offered to put him in office as a Bond nominee, but the offer was declined. When Rhodes was invited to take office after the downfall of the Sprigg ministry, however, he asked the Bond leaders to meet him and discuss the situation. His policy of customs and railway unions between the various states when added to the personal esteem which many Dutchmen at the time had for him, enabled him to undertake and to successfully carry out the business of government.

The colonies of British Bechuanaland and Basutoland were now included in the customs union between the Orange Free State and Cape Colony. Pondoland, another native territory, was added to the colony in 1894. The act dealt with natives who resided in certain native reserves and provided for their interests and holdings. It also awarded them certain privileges that they had hitherto not enjoyed, and also required them to pay a small labour tax. This was in many respects the most statesmanlike act dealing with natives on the statue-book. In the parliamentary sitting of 1895, Rhodes was able to report that the Act had been applied to 160,000 natives. The labour clauses of the act, which were not being applied, were repealed in 1905. The clauses had some success as they prompted many thousands of natives to fulfil their labour requirements to be exempted from the labour tax.

In other regards, Rhode's native policy was marked by a combination of consideration and firmness. Ever since the granting of self-government, the natives had enjoyed the right to vote. An act passed in 1892, on Rhodes' insistence, imposed an educational test on applications who wanted to register to vote as well as creating several other restrictions on the native vote as there were fears that "tribal" natives would possibly "endanger" the current system of government.

Rhodes opposed native liquor trafficking and suppressed it entirely on the diamond mines at the risk of offending some of his supporters among the brandy-farmers of the western provinces. He also restricted it as much as he could on native reserves and territories. Nevertheless, liquor trafficking continued on colonial farms and to some extent on in native territory and reserves. The Khoikhoi were particularly fond of the drink as they had been almost completely demoralised from their military losses.

A little-known instance of Rhode's keen insight in native affairs that had lasting results on the history of the colony is his actions in an inheritance case. After the territories east of the Kei River were added to the Cape Colony, an inheritance claim came up for trial. In accordance with the law of the colony, the court held that the eldest son of a native was his heir. This decision was strongly resented among the natives of the territory, as it directly contradicted native tribal law which recognised the great son, or the son of the chief wife, as heir. The government was threatened with further native rebellions when Rhodes telegraphed his assurance that compensation would be granted and that such a decision would never be made again. His assurance was accepted and tranquillity was restored.

At the end of the next parliamentary sitting after this incident occurred, Rhodes tabled a bill that he had drafted that was the shortest in the history of the House. It stated that all civil cases were to be tried by magistrates and that appeals could be launched to the chief magistrate of the territory with an assessor. Criminal cases were to be tried before supreme court judges on circuit. The bill passed with the effect that, inasmuch as the magistrates practised according to native law, that native marriage customs and laws, including polygamy, were legalised in the colony.

Sir Hercules Robinson was reappointed governor in 1895 and high commissioner of South Africa to succeed Sir Henry Loch. In the same year, Mr Chamberlain became secretary of state for the colonies.

Movement for commercial federation

With the development of railways and the increase in trade between Cape Colony and the Transvaal, politicians in both places began to debate forming a closer relationship. While acting as Premier of Cape Colony, Rhodes endeavoured to bring about the friendly gesture of commercial federation among the states and colonies of South Africa by means of a customs union. He hoped to established both a commercial and a railway union, which is illustrated by a speech he gave in 1894 in Cape Town:

- "With full affection for the flag which I have been born under, and the flag I represent, I can understand the sentiment and feeling of a republican who has created his independence, and values that before all; but I can say fairly that I believe in the future that I can assimilate the system, which I have been connected with, with the Cape Colony, and it is not an impossible idea that the neighbouring republics, retaining their independence, should share with us as to certain general principles. If I might put it to you, I would say the principles of tariffs, the principle of railway connection, the principle of appeal in law, the principle of coinage, and in fact all those principles which exist at the present moment in the United States, irrespective of the local assemblies which exist in each separate state in that country."

President Kruger and the Transvaal government found every possible objection to this policy. Their actions in what became known as the Vaal River Drift Question best illustrates the plan of action that the Transvaal government thought best. A series of disagreements arose over the termination of the 1894 agreement between the Cape government railway and the Netherlands railway. The Cape government had advanced the sum of £600,000 to the Netherlands railway and the Transvaal government conjointly for the purposes of extending the railway from the Vaal River to Johannesburg. At the same time, it was stipulated that the Cape government have the right to fix the rate of traffic until the end of 1894, or until the Delagoa Bay-Pretoria line was completed.

The rate of traffic was fixed by the Cape government at 2d. per ton per mile, but at the beginning of 1895 the rate for the 52 miles (84 km) of railway from the Vaal River to Johannesburg was raised by the Netherlands railway to no less than 8d. per ton per mile. It is evident from President Kruger's subsequent actions that these changes were based upon his personal approval with the goal of compelling traffic to the Transvaal to use the Delagoa route instead of the colonial railway. To compete with this very high rate, the merchants of Johannesburg began moving their goods across the Vaal River with wagons. In a direct response, President Kruger closed the drifts or fords on the Vaal River, preventing through-wagon traffic. This created an enormous block of wagons on the banks of the Vaal. There were several protests launched by the Cape government against the actions of the Transvaal because it was a breach of the London Convention.

President Kruger was not moved by these protests, and an appeal was made to the imperial government. The imperial government made an agreement with the Cape Government to the effect that if the Cape would bear half the cost of any necessary expedition, assist with troops, and give full use of the Cape railway for military purposes if required, a protest would be sent to President Kruger on the subject. These terms were accepted by Rhodes and his colleagues, of whom W. P. Schreiner was one, and a protest was sent by Chamberlain stating that the government regarded the closing of the drifts as a breach of the London Convention, and as an unfriendly action that called for the gravest of responses. President Kruger reopened the drifts at once, and stated that he would issue no further directives on the subject except after consultation with the imperial government.

Leander Starr Jameson made his famous raid into the Transvaal on 29 December 1895, and Rhode's complicity in the action compelled him to resign the premiership of Cape Colony in January 1896. Sir Gordon Sprigg took the vacant post. As Rhode's complicity in the raid became known, there was a strong feeling of resentment and astonishment among his colleagues in the Cape ministry who had been ignorant of his connections with such schemes. The Bond and Hofmeyr denounced him particularly strongly, and the Dutch became even more embittered against the English in Cape Colony, which influenced their subsequent attitude towards the Transvaal Boers.

There was another native uprising under a Bantu chief named Galeshwe in Griqualand West in 1897, but Galeshwe was arrested and the rebellion ended. Upon examination, Galeshwe stated that Bosman, a Transvaal magistrate, supplied him with ammunition and encouraged him to rebel against the government of Cape Colony. There was sufficient evidence to believe the charge to be true, and it was consistent with the methods the Boers sometimes used among the natives.

Sir Alfred Milner was appointed high commissioner of South Africa and governor of Cape Colony in 1897, succeeding Sir Hercules Robinson, who was made a peer under the title of Baron Rosmead in August 1896.

Schreiner’s policy

Commercial federation advanced another state in 1898 when Natal entered the customs union. A new convention was drafted at the time, creating a “uniform tariff on all imported goods consumed within such union, and an equitable distribution of the duties collected on such goods among the parties to such union, and free trade between the colonies and state in respect of all South African products”. Another Cape parliamentary election was held in the same year, which elected another Bond ministry under W. P. Schreiner. Schreiner remained as head of the Cape Government until June 1900.

During the negotiations that proceeded the outbreak of the Second Boer War in 1899, feelings were running very high at the Cape. As the head of a party that depended upon the Bond for its support, he had to balance several different influences. However, as prime minister of a British colony, loyal colonists strongly felt that he should have refrained from openly interfering with Transvaal government and the imperial government. His public statements were hostile in tone to the policy that Chamberlain and Sir Alfred Milner pursued. The effect of Schreiner's hostility is believed by some to have encouraged President Kruger in his rejection of the British proposals. In private, Schreiner directly used whatever influence he possessed to induce President Kruger to adopt a "reasonable" course, but however excellent his intentions, his publicly expressed disapproval of the Chamberlain/Milner policy did more harm than his private influence with Kruger could possibly do good.

Schreiner asked the high commissioner on 11 June 1899 to inform Chamberlain that he and his colleagues decided to accept President Kruger's Bloemfontein proposals as “practical, reasonable and a considerable step in the right direction”. Later in June, however, Cape Dutch politicians began to realise that President Kruger's attitude was not as reasonable as they had believed, and Hofmeyr, along with a Mr Herholt, the Cape Minister of Agriculture, visited Pretoria. After they arrived, they found the Transvaal Volksraad to be in a spirit of defiance and that it had just passed a resolution that offered four new seats in the Volksraad to represent the mining districts, and 15 exclusive burgher districts. Hofmeyr, upon meeting the executive, freely expressed indignation at these proceedings. Unfortunately, Hofmeyr's influence was more than counterbalanced by an emissary from the Free State named Abraham Fischer who while purporting to be a peacemaker, practically encouraged the Boer executive to take extreme measures.

Hofmeyr's established reputation as an astute diplomat and the leader of the Cape Dutch Party made him a powerful delegate. If anyone could convince Kruger to change his plan, it was Hofmeyr. The moderates on all sides of the issue looked to Hofmeyr expectantly, but none as much as Schreiner. But Hofmeyr's mission, like every other such mission to induce Kruger to take a "reasonable" and equitable course, proved entirely fruitless. He returned to Cape Town disappointed, but not altogether surprised at the failure of his mission. Meanwhile, the Boer executive drafted a new proposal which prompted Schreiner to write a letter on 7 July to the South African News, in which while referring to his own government, he said: “While anxious and continually active with good hope in the cause of securing reasonable modifications of the existing representative system of the South African Republic, this government is convinced that no ground whatever exists for active interference in the internal affairs of that republic.”

The letter proved to be precipitate and unfortunate. On 11 July, after meeting with Hofmeyr after his return, Schreiner personally appealed to President Kruger to approach the imperial government with a friendly spirit. Another incident happened at the same time that caused public feeling to become extremely hostile towards Schreiner. On 7 July 500 rifles and 1,000,000 rounds of ammunition were off shored at Port Elizabeth, consigned to the Free State government, and forwarded to Bloemfontein. The consignment was brought to Schreiner's attention, but he refused to stop it. He justified his decision by saying that since Britain was at peace with the Free State, he had no right to stop the shipment of arms through the Cape Colony. However, his inaction won him the sobriquet "Ammunition Bill" among British colonists. He was later accused of a delay in forwarding artillery and rifles to defend Kimberley, Mafeking, and other towns in the colony. He gave the excuse that he did not anticipate war, and that he did not want to create unwarranted suspicions in the minds of the Free State government. His conduct in both instances was perhaps technically correct, but was much resented by loyal colonists.

Chamberlain sent a conciliatory message to President Kruger on 28 July, suggesting a meeting of delegates to consider the latest set of proposals. On 3 August, Schreiner telegraphed Fischer begging the Transvaal to accept Chamberlain's proposal. Later, after receiving an inquiry from the Free State amount the movements of British troops, Schreiner curtly refused to disclose any information, and referred the Free State to the high commissioner. On 28 August, Sir Gordon Sprigg moved the adjournment in the House of Assembly to discuss the removal of arms from the Free State. In reply, Schreiner used expression which demanded the strongest possible censure of Sprigg possible, both in the colony and in Britain. Schreiner stated that should troubles arise, Sprigg would keep the colony aloof in regard to both its military and its people. In the course of his speech, he read a telegram from President Steyn in which the president repudiated all possible aggressive action on any part of the Free State as absurd. The speech created a scandal in the British press.

It is quite obvious from a review of Schreiner's conduct through the latter half of 1899 that he was entirely mistaken in his view of the Transvaal situation. He demonstrated the same inability to understand the uitlanders’ grievances, the same futile belief in the eventual fairness of President Kruger as premier of Cape Colony as he had shown when giving evidence before the British South Africa Select Committee into the causes of the Jameson Raid. Experience should have taught him that President Kruger was beyond any appeal to reason, and that the protestations of President Steyn were insincere.

References

- R.W. Murray (Limner): Pen and Ink Sketches in Parliament & South African Reminiscences. Cape Town: UCT Libraries. 1965.

- J.L. McCracken: The Cape Parliament, 1854-1910. London: Caledon Press. 1967.

- Wilmot, A. The History of our own Times in South Africa, Volume 2. J.C. Juta & co., 1899

- Molteno, P. A. The Life and Times of John Charles Molteno. Comprising a History of Representative Institutions and Responsible Government at the Cape, Volume II. London: Smith, Elder & Co., Waterloo Place, 1900. p.214.

- F. Statham: Blacks, Boers, & British: A Three-cornered Problem. MacMillan & Co. 1881.

- V.C.Malherbe: What They Said. 1795–1910 History Documents. Cape Town: Maskew Miller. 1971. p.144-145.

- N. Mostert: Frontiers: The Epic of South Africa's Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People. Pimlico: London, 1993. ISBN 0-7126-5584-0, p.1247.

- Frank Richardson Cana: South Africa: From the Great Trek to the Union. London: Chapman & Hall, ltd., 1909. Chapter VII "Molteno’s Unification Plan". p.89

- Illustrated History of South Africa. The Reader's Digest Association South Africa (Pty) Ltd, 1992. ISBN 0-947008-90-X. p.182, "Confederation from the Barrel of a Gun"

Further reading

- The Migrant Farmer in the History of the Cape Colony.P.J. Van Der Merwe, Roger B. Beck. Ohio University Press. 1 January 1995. 333 pages. ISBN 0-8214-1090-3.

- History of the Boers in South Africa; Or, the Wanderings and Wars of the Emigrant Farmers from Their Leaving the Cape Colony to the Acknowledgment of Their Independence by Great Britain. George McCall Theal. Greenwood Press. 28 February 1970. 392 pages. ISBN 0-8371-1661-9.

- The Life and Times of John Charles Molteno. Comprising a History of Representative Institutions and Responsible Government at the Cape. P. A. Molteno. London: Smith, Elder & Co., Waterloo Place, 1900.

- Illustrated History of South Africa. The Reader's Digest Association South Africa (Pty) Ltd, 1992. ISBN 0-947008-90-X.

- Status and Respectability in the Cape Colony, 1750–1870 : A Tragedy of Manners. Robert Ross, David Anderson. Cambridge University Press. 1 July 1999. 220 pages. ISBN 0-521-62122-4.

- The War of the Axe, 1847: Correspondence between the governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Henry Pottinger, and the commander of the British forces at the Cape, Sir George Berkeley, and others. Basil Alexander Le Cordeur. Brenthurst Press. 1981. 287 pages. ISBN 0-909079-14-5.

- Blood Ground: Colonialism, Missions, and the Contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 1799–1853. Elizabeth Elbourne. McGill-Queen's University Press. December 2002. 560 pages. ISBN 0-7735-2229-8.

- Recession and its aftermath: The Cape Colony in the eighteen eighties. Alan Mabin. University of the Witwatersrand, African Studies Institute. 1983. 27 pages. ASIN B0007B2MXA.