Homestake Mine (South Dakota)

The Homestake Mine was a deep underground gold mine located in Lead, South Dakota. Until it closed in 2002 it was the largest and deepest gold mine in North America. The mine produced more than forty million troy ounces (43,900,000 oz; 1,240,000 kg) of gold during its lifetime.[1] This is about 70.75 m3 or a volume of gold roughly equal to 18 677 gallons (a cube with each side being roughly 4.14 metres).

The Homestake Mine is famous in scientific circles because of the work of a deep underground laboratory that was set up there in the mid-1960s. This was the site where the solar neutrino problem was first discovered, in what is known as the Homestake Experiment. Raymond Davis Jr. conducted this experiment in the mid-1960s, which was the first to observe solar neutrinos.

On July 10, 2007, the mine was selected by the National Science Foundation as the location for the Deep Underground Science and Engineering Laboratory (DUSEL).[2] It won over several candidates, including the Henderson Mine near Empire, Colorado.

History

The Homestake deposit was discovered by Fred and Moses Manuel, Alex Engh, and Hank Harney in April 1876, during the Black Hills Gold Rush, when gold was discovered in the Black Hills, an area that had been guaranteed to the Lakota Nation by the Fort Laramie Treaty. A trio of mining entrepreneurs, George Hearst, Lloyd Tevis, and James Ben Ali Haggin, bought the claim from them for $70,000 in 1877.

George Hearst reached Deadwood in October 1877, and took active control of the mine property. Hearst had to arrange to haul in all the mining equipment by wagons from the nearest railhead in Sidney, Nebraska. Arthur De Wint Foote worked as an engineer.[3] Despite the remote location, deep mines were dug and ore began to be brought out. An 80-stamp mill was built and began crushing Homestake ore by July 1878.

In 1879 the partners sold shares in the Homestake Mining Company, and listed it on the New York Stock Exchange. The Homestake would become one of the longest-listed stocks in the history of the NYSE, as Homestake operated the mine until 2001.

Hearst consolidated and enlarged the Homestake property by fair and foul means. He bought out some adjacent claims, and secured others in the courts. A Hearst employee killed a man who refused to sell his claim, but was acquitted in court after all the witnesses disappeared. Hearst purchased newspapers in Deadwood to influence public opinion. An opposing newspaper editor was physically attacked on a Deadwood street. Hearst realized that he might be on the receiving end of violence, and wrote a letter to his partners asking them to provide for his family should he be murdered. But within three years, Hearst had established the mine and acquired significant claims; he walked out alive, and very rich.[4]

By the time Hearst left the Black Hills in March 1879, he had added the claims of Giant, Golden Star, Netty, May Booth, Golden Star No. 2, Crown Point, Sunrise, and General Ellison to the original two claims of the Manuel Brothers, Golden Terra and Old Abe, totaling 30 acres (12 ha). The ten-stamp mill had become 200, and 500 employees worked in the mine, mills, offices and shops. Hearst owned the Boulder Ditch and water rights to Whitewood Creek, monopolizing the region. His railroad, Black Hills & Fort Pierre Railroad, gave him access to eastern Dakota Territory.[5]

By 1900, Homestake owned 300 claims, on 2,000 acres (810 ha), and was worked by more than 2000 employees.[5]:35,40,42 In 1901, the mine started using compressed air locomotives, fully replacing mules and horses by the 1920s. Charles Washington Merrill introduced cyanidization to augment mercury-amalgamation for gold recovery. "Cyanide Charlie" achieved 94 per cent recovery. The gold was shipped to the Denver Mint.[5]:49–51

By 1906, the Ellison Shaft reached 1,550 feet (472 m), the B&M 1,250 feet (381 m), the Golden Star 1,100 feet (335 m), and the Golden Prospect 900 feet (274 m), producing 1,500,000 short tons (1,300,000 long tons; 1,400,000 metric tons) of ore. A disastrous fire struck on 25 March 1907, which took forty days to extinguish after the mine was flooded. Another disastrous fire struck in 1919.[5]:52–53,59

In 1927, company geologist Donald H. McLaughlin used a winze from the 2,000 level to demonstrate that ore reached the 3,500 foot level. The Ross shaft was started in 1934, a second winze from the 3,500-foot (1,100 m) level reached 4,100 feet (1,250 m), and a third winze from 4,100 feet (1,250 m) was started in 1937. The Yates shaft was started in 1938. Production ceased during World War II from 1943 until 1945, due to Limitation Order L-208 from the War Production Board. By 1975, mining operations had reached the 6,800-foot (2,073 m) level, and two winzes were planned to 8,000 feet (2,438 m).[5]:63–66,73–74

The gold ore mined at Homestake was considered low grade (less than one ounce per ton), but the body of ore was very large.[6] Through 2001, the mine produced 39,800,000 troy ounces (43,700,000 oz; 1,240,000 kg) of gold and 9,000,000 troy ounces (9,870,000 oz; 280,000 kg) of silver. In terms of total production, the Lead mining district, of which the Homestake mine is the only producer, was the second-largest gold producer in the United States, after the Carlin district in Nevada. Homestake was the longest continually operating mine in United States history.

_(14736672692).jpg.webp)

The Homestake mine ceased production at the end of 2001. Reasons included low gold prices, poor ore quality, and high costs.

Conversion to use for scientific research

The Barrick Gold corporation (which had merged with the Homestake Mining Company in mid-2001) agreed in early 2002 to keep dewatering the mine while owners were negotiating with the National Science Foundation over the mine as a potential site for a new deep underground laboratory (DUSEL). But progress was slow and maintaining the pumps and ventilation was costing $250,000 per month.[7] The owners switched the equipment off on June 10, 2003 and closed the mine completely.[8]

The Homestake Mine was selected in 2007 by NSF for the Deep Underground Science and Engineering Laboratory (DUSEL). In June 2009, researchers at University of California Berkeley announced that Homestake would be reopened for scientific research on neutrinos and dark matter particles using DUSEL and Large Underground Xenon experiment.[9]

Research into enhanced geothermal systems is also being prepared in the mine.[10]

Geology

The gold at Homestake is almost exclusively confined to the Homestake Formation, an Early Proterozoic layer with iron carbonate and iron silicate. The original 20–30 m thick Homestake Formation, has been deformed and metamorphosed, resulting in upper greenschist facies of siderite-phyllite, and lower amphibolite facies of grunerite schists.[11]:J15

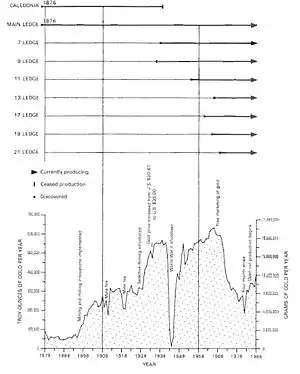

The iron may have been deposited by volcanic exhalation, perhaps in the presence of microorganisms[11]:J17 as a banded iron formation. Gold ore mineralization is most intense in the Main Ledge, at the surface, and the 9 Ledge, at the 3200 level (feet below the Incline Shaft, at 1594 m above sea level).[11]:J36

Geologic map of the Black Hills[11]

Geologic map of the Black Hills[11] Geologic cross section. The Homestake Formation has been deformed into synclines, odd numbers, and anticlines, even numbers. Ore mineralization occurred mainly in the synclines, called Ledges.[11]:J36

Geologic cross section. The Homestake Formation has been deformed into synclines, odd numbers, and anticlines, even numbers. Ore mineralization occurred mainly in the synclines, called Ledges.[11]:J36 Lead Geologic Map. Note the locations of the Ellison, Old Abe, Highland, Deadwood Terra, and DeSmet shafts, south to north. The Caledonia Cut is labelled with a "1".[12]:14

Lead Geologic Map. Note the locations of the Ellison, Old Abe, Highland, Deadwood Terra, and DeSmet shafts, south to north. The Caledonia Cut is labelled with a "1".[12]:14 Lead Geologic Map Legend[12]

Lead Geologic Map Legend[12]

See also

- Raymond Davis Jr.

- Solar neutrino problem

- Colorado Mineral Belt, regarding the Henderson Mine

- Volcanogenic massive sulfide ore deposit (VMS), the base-metal rich equivalent to Homestake

- Cash, Joseph H. (1973). Working the Homestake. Ames: Iowa State University Press. ISBN 0-8138-0755-7.

References

- Yarrow, Andrew L. (August 9, 1987). "Beneath South Dakota's Black Hills". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

Homestake, which is the largest, deepest and most productive gold mine in North America, has yielded more than $1 billion in gold over the years.

- "Team Selected for the Proposed Design of the Deep Underground Science and Engineering Laboratory" (Press release). The National Science Foundation. July 10, 2007. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- Rickard, Thomas Arthur (1922). Interviews with Mining Engineers. San Francisco: Mining and Scientific Press. pp. 173–174. OCLC 2664362.

- Smith, Duane A. (September 2003). "Here's to low-grade ore and plenty of it, the Hearsts and the Homestake Mine". Mining Engineering: 23–27.

- Bronson, W., and Watkins, T.H., Homestake, San Francisco: Homestake Mining Company, 1977

- Slaughter, A.L. (1968). "The Homestake Mine". In Ridge, John Drew (ed.). Ore Deposits of the United States, 1933-1967. New York: American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers. pp. 1436–1459.

- Chang, Kenneth (June 11, 2003). "Flooding of S. Dakota Mine Stalls Plans for Laboratory". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- "The Drive for DUSEL". South Dakota Ready to Work. August 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2011. Retrieved 2010-02-23. A history of the Homestake mine as it applies to DUSEL.

- Sanders, Robert (June 17, 2009). "Berkeley stakes science claim at Homestake gold mine". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- Metcalfe, Elisabet (2017-11-28). "A Group of Scientists Walk Into a Mine ..." Energy.gov. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- Caddey, S.W., Bachman, R.L., Campbell, T.J., Reid, R.R., and Otto, R.P., 1991, The Homestake Gold Mine, An Early Protozoroic Iron-Formation-Hosted Gold Deposit, Lawrence County, South Dakota, in Geology and Resources of Gold in the United States, USGS Bulletin 1857, Washington: United States Government Printing Office

- Paige, S., 1924, Geology of the Region Around Lead South Dakota, USGS Bulletin 765, Washington:Government Printing Office

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homestake Mine. |

- Homestake mine visitors center website

- Sanford Underground Laboratory at Homestake

- Homestake DUSEL

- Black Hills Geology photo album, mostly of the mine area, by geologist James St. John