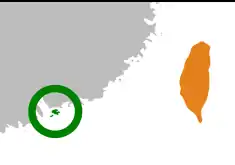

Hong Kong–Taiwan relations

Relations between the government of Hong Kong and the Republic of China (Taiwan) encompass both when the Republic of China controlled mainland China, and afterwards, when the Republic of China fled to Taiwan.

| |

Hong Kong |

Taiwan |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Hong Kong | Hong Kong Economic, Trade and Cultural Office, Taipei |

History

Before 1842, both regions were part of the Qing dynasty; in 1842, Hong Kong Island was ceded to the British Empire as a result of the First Opium War, and in 1895, Taiwan was ceded to the Empire of Japan as a result of the First Sino-Japanese War. Sun Yat-sen was a student in Hong Kong in the late 1800s and believed that the Qing dynasty's ineffectiveness and loss in the First Sino-Japanese War necessitated a revolution to replace Chinese dynasties with a modern republic. In 1888, he was pictured in Hong Kong as a member of the Four Bandits, a group that met to discuss overthrowing the Qing dynasty,[1] and in 1894, he began the formation of the Revive China Society to overthrow the Qing dynasty. On 21 February 1895, while at a Revive China Society meeting in Hong Kong, Lu Haodong presented his Blue Sky with a White Sun design, which became the emblem of the Republic of China.[2] The Revive China Society was headquartered at 13 Staunton Street[3] in Hong Kong, and in 1905 it was merged with other groups to form the Tongmenghui. This organization had wide support among Chinese, and played a key role[4] in uprisings started by revolutionaries, including the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, which overthrew the Qing dynasty. After the success of the Xinhai Revolution, Sun Yat-sen declared the establishment of the Republic of China on 1 January 1912, and was inaugurated as the first provisional president. Later that same year in August 1912, the Tongmenghui merged with other groups to create the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party), and Sun Yat-sen was chosen as its leader.

Sun Yat-sen returned to Hong Kong in 1923 to visit the University of Hong Kong, which had incorporated the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese as its medical school, of which Sun Yat-sen was an early alumni. During his visit at HKU, he gave a speech[5] and declared Hong Kong's inspiration to him in the revolutions that eventually created the Republic of China: "That is the answer to the question, where did I get my revolutionary ideas: it is entirely in Hong Kong." In addition to being the origin of his revolutionary ideas, Hong Kong also offered protection to some of his family members; Sun Yat-sen's mother, Lady Yang, resided with his eldest brother, Dezhang, in Kowloon City, after Sun Yat-sen was placed on a wanted list by the Qing government.[6] With Sun Yat-sen's death in 1925, Chiang Kai-shek became leader of the KMT and Sun Yat-sen's successor, eventually unifying China under the Nationalist government in 1928.

The United States and Decolonization

Longstanding United States policy held the belief that China should not be colonized; the United States, in 1899 had advocated the Open Door Policy, which communicated that China should not be partitioned and colonized. The Nine-Power Treaty in 1922, signed by the British, affirmed the Open Door Policy and territorial integrity of China. In July of 1940, Winston Churchill declared in Parliament that "We desire to see China's status and integrity preserved, and as was indicated in our Note of 14th January, 1939, we are ready to negotiate with the Chinese Government, after the conclusion of peace, the abolition of extraterritorial rights, the rendition of concessions and the revision of treaties on the basis of reciprocity and equality[7]," affirming territorial integrity and relinquishment of extra-territorial rights in China. The idea of territorial integrity and decolonization was further encapsulated in the August 1941 Atlantic Charter statement, issued by Franklin Roosevelt (who was staunchly against colonialism[8]) and Winston Churchill, stipulating that "territorial adjustments must be in accord with the wishes of the peoples concerned." Though Winston Churchill did not want British colonies to decolonize, he agreed to the Atlantic Charter's decolonization provisions "to get the Americans into the war" with military aid on the side of the Allies.[9] On 1 January 1942, the Declaration of the United Nations was signed by the Big Four (the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Republic of China), stipulating that the Atlantic Charter's pledges should be upheld, which later became the basis of the Charter of the United Nations in 1945.

Hong Kong during World War II

In January 1941,[10] as the Japanese military advanced in mainland China towards Hong Kong, UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill was reluctant to defend the colony, and said that defensive troops should be reduced to a "symbolical scale" there.[11] With a quick victory by the Japanese against the weakly-defended colony in December 1941, the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong began, and both Hong Kong and Taiwan were subjects of the Empire of Japan.

Also that same month in December 1941, the United States entered World War II, several months after issuing the Atlantic Charter and having Churchill agree to decolonize. Despite the weak protection of Hong Kong and agreements by the British to the Nine-Power Treaty, Atlantic Charter, and Declaration of the United Nations, the British refused to decolonize and have Hong Kong handed over to the Republic of China. In 1942, the Republic of China repealed the unequal treaties and began negotiations with the United Kingdom on the establishment of a new, fairer treaty. Chiang Kai-Shek attempted to put the issue of Hong Kong onto the two parties' agenda, suggesting that the Kowloon concession should be returned to the Republic of China along with the other foreign concessions. This was fiercely rejected by Winston Churchill, and the United Kingdom also demanded that the Republic of China give their written consent that the Kowloon concession was not included within the unequal treaties, or else they would refuse to sign, and so the Republic of China was forced to drop the concession of Kowloon from the agenda. In 1943, the two sides signed the Sino-British New Equal Treaty, with the Republic of China writing a formal letter to the United Kingdom and securing the right to raise the issue of Hong Kong on a later occasion.[12]

After World War II

Before the surrender of Japan at the end of World War II, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt promised Soong Mei-ling, wife of Chiang Kai-shek, that Hong Kong would be restored to Republic of China control. However, at the end of the war, the British moved quickly to regain control of Hong Kong[13] in August 1945, preventing the unification of Hong Kong and the Republic of China (ROC). After the loss in the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the Kuomintang-ruled Republic of China government, started by Sun Yat-sen, fled to Taiwan in the Great Retreat. Shortly after, on 6 January 1950, the UK recognized the People's Republic of China (PRC) as the government of China due to economic interests, and blocked the Republic of China government from participating in the Treaty of San Francisco in 1951, which introduced the issue of which government Taiwan was to be surrendered to. In 1957, UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had a secret agreement with the United States, where the United States agreed to defend Hong Kong with the British as a "joint defense problem" in case it was attacked by communist China.[14] In exchange, the British pledged to not push for communist China's membership in the United Nations,[14] which would leave the UN seat with Taiwan. However, in 1971, United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758 was supported by the British and passed, recognizing the PRC as the legitimate government of China in the UN rather than the Republic of China. Afterwards, the British and People's Republic of China began negotiations on the Handover of Hong Kong, ultimately sealing Hong Kong's future with the PRC rather than the ROC.

Both during and after the Chinese Civil War, many people from Mainland China, including pro-Kuomintang refugees and former soldiers, fled to both Hong Kong and Taiwan. By mid-1950, around 10,000 Nationalist soldiers had arrived in Hong Kong, temporarily held on a fort on Mount Davis.[14] In June of 1950, the soldiers were targeted by pro-Communists in violent clashes, leading to the relocation of 6,000 of the targeted soldiers a week later to Rennie's Mill.[14] An additional 10,000-20,000 Nationalist refugees settled at Rennie's Mill, where the Hong Kong Rennie's Mill Refugee Camp Relief Committee (HKRMRC) was set up with Nationalist funds from Taiwan's Free China Relief Association (FCRA).[14] The FCRA began setting up a permanent pro-Nationalist, anti-Communist community in Hong Hong, earning Rennie's Mill the nickname "Little Taiwan."[14] Several thousand of the most enthusiastic pro-Nationalists were transported by the FCRA to Taiwan.[14]

Nationalists and refugees also settled at the Kowloon Walled City, attracting 2,000 squatters by 1947, who were convinced that the area was under jurisdiction by the ROC.[15] Earlier in 1933, the Nationalist government claimed jurisdiction over the area and began pressuring the British government over the issue.[16] In late 1946, Nationalist government officials visited the site and made a plan to administer the area, creating the "Draft Outline Plan for Reinstatement of Administration."[17] Shortly after in January 1948, KMT officials entered the area and encouraged residents to resist eviction by the colonial government, eventually leading to riots in the Walled City and student protests in ROC-controlled mainland China, where the British consulate in Canton was looted and set on fire.[16]

After the Civil War, the Pro-Taiwan camp was a major political force in Hong Kong. Additionally, operations against communists by pro-Nationalists in Hong Kong were particularly intense in the late 1950s to the early 1960s.[14] On Double Ten Day, flags of the Republic of China were frequently seen in Hong Kong; the ordering of the removal[18] of one flag by a junior government official caused the Hong Kong 1956 Riots, when pro-Nationalists (called "Rightists") fought against Pro-Communists (called "Leftists"). Though the flying of the Republic of China flag during Double Ten Day flag has decreased since the 1997 handover, it can still be seen to this day[19][20] at places including Hung Lau in Tuen Mun, where an obelisk and bust of Sun Yat-sen are located.

Official relations and politics

Since 2010, the relationship between Hong Kong and the ROC is managed through the Hong Kong-Taiwan Economic and Cultural Co-operation and Promotion Council (ECCPC) and Taiwan-Hong Kong Economic and Cultural Co-operation Council (THEC). Meanwhile, the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Hong Kong (TECO) is the representative office of the Republic of China in Hong Kong, while the Hong Kong Economic, Trade and Cultural Office (HKETCO) is the representative office of Hong Kong in the Republic of China.[21] In addition, the relations with Hong Kong is also conducted by the Mainland Affairs Council, although not all regulations applicable to mainland China are automatically applied to those territories.

In recent times, both regions have been involved with each other politically. In 2014, students from Hong Kong supported Taiwan's Sunflower Student Movement, and students from Taiwan supported the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong.[22][23] The 2018 murder by a Hong Kong citizen while in Taiwan caused the Hong Kong government to propose the Hong Kong extradition bill in 2019, which would have allowed suspected criminals to be extradited to not just Taiwan, but Mainland China and Macau as well. This began massive protests in Hong Kong, with the government of Taiwan supporting the protesters, not wanting the proposal to become law.[24] The government of Taiwan sees the extradition bill, now withdrawn, as an infringement of the one country, two systems principle, which has been the PRC's proposal for unification with Taiwan. Tens of thousands of Taiwanese citizens marched in Taipei on 29 September 2019 in support of Hong Kong's pro-democracy movement.[25] Because of Taiwan's support of the protests, ROC flags have been frequently seen at protests.[19]

In July 2020, TECO's highest officer in Hong Kong, Kao Ming-tsun, was not granted a renewal of his work visa by the Hong Kong government because he refused to sign a statement supporting the "One China" principle.[26] The Mainland Affairs Council of Taiwan mentioned that other government representatives in TECO had experienced major visa delays from the Hong Kong government as well.[26]

Refugee Status

Joshua Wong, a politician from Hong Kong, has also traveled to Taiwan to meet with the government to discuss the potential for Hong Kong protesters to seek political asylum in Taiwan.[27][28] Keith Fong Chung-yin, president of the Hong Kong Baptist University Student Union, also echoed Joshua Wong's remarks about the lack of an asylum process in Taiwan and says the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has not enacted specific laws to help refugees.[29][30] Though Tsai Ing-wen, the president of Taiwan, has regularly supported the protesters on social media and Article 18 of Taiwan's Laws and Regulations Regarding Hong Kong & Macao Affairs stipulates that "Necessary assistance shall be provided to Hong Kong or Macau Residents whose safety and liberty are immediately threatened for political reasons[31]," the government of Taiwan has not created a process for political refugees yet.[32][33] Joseph Wu, Taiwan's Minister of Foreign Affairs, has said that existing legislation to deal with refugees is sufficient,[34] even though a New York Times video[35] has shown that some refugees from Hong Kong have entered Taiwan illegally, providing evidence that existing legislation is not sufficient. A Hong Kong Free Press article mentions that people usually use speed boats to flee from Hong Kong to Taiwan.[36] In response to the New York Times video, the Mainland Affairs Council warned protesters to not enter Taiwan illegally, and reiterated the statement that existing laws are sufficient,[37] even though they only cover special cases, such as student, investment, and tourist visas. For student visas, Taiwan's Ministry of Education in November of 2019 announced that university students in Hong Kong would be allowed to attend lectures and continue their studies in Taiwan.[38] For refugees who do not qualify for student and investment visas, this lack of a formal asylum process means that they enter Taiwan on 30-day tourist visas[39][40] and cannot legally work in Taiwan.

In contrast to the DPP's position of believing current laws are adequate, Han Kuo-yu, the Kuomintang's losing candidate for the 2020 Taiwan presidential election, has said that he fully supports the passage of a refugee law to help asylum seekers from Hong Kong.[41] In addition, the New Power Party (NPP) in April 2020 requested that the DPP and Legislative Yuan pass a refugee act, as well as amend Article 18 so that procedures are clearly defined for political refugees from Hong Kong.[42][43] As of May 2020, despite DPP President Tsai Ing-wen and Minister of Foreign Affairs Joseph Wu claiming that existing legislation is sufficient, no resident of Hong Kong of Macau has received official assistance from Taiwan under Article 18.[36] Chairman of the KMT, Johnny Chiang, has also said that the DPP administration under Tsai has been vocal about helping those from Hong Kong but has failed to provide any meaningful help, and that legislation should be passed to grant political asylum to those from Hong Kong. In regards to the failure of the DPP to enact laws regarding this, Chiang also said that "Don't let 'supporting Hong Kong' only be a slogan of empty promises... Bring up your thoughts on legislation. Support Hong Kong with real actions."[44]

Despite Taiwan's lack of progress on officially granting refugee status, some in Hong Kong have fled to Taiwan, including Causeway Bay Books founder Lam Wing-kee. Lam has said that Taiwan is the "last fortress" for Hong Kong residents against mainland Chinese oppression, and that young Hong Kongers should leave to Taiwan.[43] However, without refugee laws in Taiwan, it is not clear on how young Hong Kongers would accomplish this; Lam himself fundraised $200,000 US Dollars for his new bookstore,[43] which is the amount needed for an investment visa in Taiwan.[45]

As Taiwan's Mainland Affairs Council does not provide assistance to those who flee to Taiwan, NGOs have taken a more active role in helping those people.[36] Chè-lâm Presbyterian Church in Taiwan has assisted those fleeing from Hong Kong to Taiwan by providing shelter to them, as well as sending supplies to protesters still in Hong Kong.[36] Goobear Chen, Chairman of the National Students’ Union of Taiwan, says, "The fundamental mission of Taiwan NGOs is to put pressure on the government to amend the refugee law," as NGOs cannot provide assistance on a long-term basis, and lawfully admitting refugees would be most effective.[36]

On 27 May 2020, President Tsai Ing-wen announced that a plan would be created to provide humanitarian support to those from Hong Kong.[46] On 18 June 2020, the plan's details were revealed; a Taiwan-Hong Kong Service and Exchange Office is set to open on 1 July 2020 in Taipei under the THEC, which intends to work with human rights and civil groups to help people with basic living expenses, residency, settlement, employment, and protection issues.[46] Any support from the office is to be provided only after people enter Taiwan.[46] No announcement was made regarding implementation of a refugee/asylum law, and those seeking help are referred to by the government as "shelter seekers" rather than "refugees."[46]

In late July 2020, 5 people from Hong Kong were found at sea by Taiwan's Coast Guard, drifting towards Pratas Island after their ship had run out of fuel.[47] Hong Kong's security chief, John Lee, warned Taiwan against "harbouring criminals" and asked for the 5 to be returned to Hong Kong, despite the lack of an extradition agreement.[48] On 26 August 2020, 12 people from Hong Kong were found by the mainland Chinese Coast Guard; in both incidents, the passengers are believed to have wanted to flee to Taiwan.[49]

According to Taiwan's National Immigration Agency (NIA), there has been an upward trend in residency permits for Hong Kongers moving to Taiwan under the 16 different programs for obtaining a residency permit.[50] In 2018, there were 4,148 issued residency permits and an additional 1,090 permanent residency grants, and in 2019, 5,858 residency permits were issued along with 1,474 permanent residency grants.[51] In 2020, 10,813 residency permits were issued.[52] An official from the NIA stated that the upward trend has a lot to do with the recent political situation in Hong Kong.[50]

Cultural and economic relations

Culturally, though the primary regional language of Hong Kong is Cantonese and the primary language of Taiwan is Mandarin, both regions continue to use Traditional Chinese characters, in contrast to Simplified Chinese characters.

As a result of the war, no direct flights were allowed between Taiwan and Mainland China; thus many passengers transferred through Hong Kong until 2003, when the Cross-Strait charter was created. Travel between nationals of the two regions is popular; in 2018, there were approximately 1.7 million nationals of Taiwan who traveled to Hong Kong, the third-most destination after Japan (4.8 million) and Mainland China (4.1 million).[53] These 1.7 million nationals represented Hong Kong's second-most inbound tourists, only after tourists from Mainland China.[54] Non-stop flights are operated between Hong Kong and Taipei (Taoyuan), Taichung, Tainan, and Kaohsiung airports.

Hong Kong and Taiwan invested heavily in education and infrastructure after World War II, causing both economies to significantly improve and be part of the Four Asian Tigers.

See also

References

- "The 130-year history of the faculty of medicine at HKU". South China Morning Post. 24 December 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "National flag". english.president.gov.tw. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- "Original Site of Xing Zhong Hui (Revive China Society) Hong Kong Headquarters".

- "Xinhai Revolution | Facts, Summary, Uprising, Revolution & Aftermath". School History. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "The Man.The University.The History - Sun Yat-sen". 100.hku.hk. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- "Dr Sun Yat-sen Museum tells story of Dr Sun's first wife, Lu Muzhen (with photos)". www.info.gov.hk. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "TRANSIT OF WAR MATERIAL TO CHINA. (Hansard, 18 July 1940)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ""That Hell-hole Of Yours" | AMERICAN HERITAGE". www.americanheritage.com. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Milestones: 1937–1945 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "The Fall of Hong Kong". www.hksw.org. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Why Churchill didn't want Hong Kong defended against Japanese". South China Morning Post. 7 January 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- 大陸委員會 (22 March 2009). "中華民國大陸委員會". 大陸委員會. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Liberating Hong Kong". End of Empire. 28 August 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Hong Kong in the Cold War. Hong Kong University Press. 2016. ISBN 978-988-8208-00-5.

- Crawford, James (6 January 2020). "The Strange Saga of Kowloon Walled City". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Miners, N. J. (1982). "A Tale of Two Walled Cities: Kowloon and Wiehaiwei". Hong Kong Law Journal. 12: 179.

- "The History of Planning for Kowloon City" (PDF). HKU.

- "What sparked Hong Kong's Double Tenth riots". South China Morning Post. 7 October 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Hong Kong protesters gather to mark Taiwan's 'Double Tenth' holiday". South China Morning Post. 10 October 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Double Tenth day: the disappearing flags of the Republic of China in Hong Kong". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Taiwanese Overseas 'Embassies' Abroad

- "Occupy takes seed of an idea from sunflower movement". South China Morning Post. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "US-China Economic and Security Review Commission 2014 report on Hong Kong" (PDF).

- Steger, Isabella. "Why Taiwan is the most outspoken critic of Hong Kong's extradition law". Quartz. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Huge crowd rallies in Taipei to support Hong Kong democracy movement". focustaiwan.tw. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Taiwan official leaves Hong Kong after refusing to sign 'One China' statement - report". Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. 17 July 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- hermesauto (3 September 2019). "Activist Joshua Wong urges Taiwanese to show support for Hong Kong". The Straits Times. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Refugee bill does not apply to Hong Kong protesters for now, Taiwan says". South China Morning Post. 5 September 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "HK student leader says Taiwan's asylum ..." Taiwan News. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Taiwanese president Tsai denies 'using' Hong Kong protests for election". South China Morning Post. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Act Governing Relations with Hong Kong and Macau". Mainland Affairs Council. 14 August 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Friends from Hong Kong: Taiwan's Refugee Problem". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Some Hong Kong Protesters Are Seeking Refuge In Taiwan. For Taiwan, It's Complicated". NPR.org. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "AP Interview: Taiwan may help if Hong Kong violence expands". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Times, The New York (8 December 2019). "Protesters Are Fleeing Hong Kong. A Secret Network Is Helping Them". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Today's Hong Kong, tomorrow's Taiwan: Protesters find help and sympathy across the strait". Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. 24 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "HK protesters warned not to flee to Taiwan illegally - RTHK". news.rthk.hk. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Taiwan universities open doors to students fleeing Hong Kong". South China Morning Post. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "'We Are Fleeing the Law': Hong Kong Protesters Escape to Taiwan". The New York Times. 8 December 2019. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Aspinwall, Nick (6 December 2019). "Why Taiwan Won't Welcome China's Dissidents". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Enact refugee law to help Hong Kong, Taiwan presidential hopeful says". Reuters. 12 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "NPP calls for Tsai to make clear stance on HK arrests - Taipei Times". www.taipeitimes.com. 19 April 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Bookseller urges external HK resistance - Taipei Times". www.taipeitimes.com. 26 April 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Reuters (24 May 2020). "Taiwan Promises 'Necessary Assistance' to Hong Kong's People". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Immigrate to Taiwan and apply for Resident visa for investment | Residencies.IO". residencies.io. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Taiwan announces humanitarian aid plan for people fleeing Hong Kong". South China Morning Post. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Hong Kong steps up maritime patrols amid reports of activists fleeing to Taiwan". South China Morning Post. 29 August 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "Hong Kong steps up pressure on Taiwan over five detained residents". South China Morning Post. 14 September 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Woman among 12 Hongkongers in sea arrest 'denied right to meet lawyer'". South China Morning Post. 6 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "Hong Kongers granted residency in Taiwan jump 116% - Focus Taiwan". focustaiwan.tw (in Chinese). Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "Hong Kong residents, protesters flock to Taiwan, but is it the right destination?". South China Morning Post. 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- "National security law prompts record number of Hongkongers to move to Taiwan: report | Apple Daily". Apple Daily 蘋果日報 (in Chinese). Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- 交通部觀光局行政資訊網. "Tourism Statistics". admin.taiwan.net.tw. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Tourism Commission - Tourism Performance". www.tourism.gov.hk. Retrieved 29 October 2019.