Hornepayne

Hornepayne is a township of 980 people (Canada 2016 Census) in the Algoma District of Ontario, Canada. The town was established in 1915 as Fitzback when the Canadian Northern Railway's transcontinental line was built through the area. It was renamed Hornepayne in 1920 after British financier Robert Horne-Payne.[2][3] The municipality was originally named Wicksteed Township after the geographic township in which it is located. It was renamed Hornepayne, after its primary community, in 1986.

Hornepayne | |

|---|---|

| Township of Hornepayne | |

| |

Logo of the Township of Hornepayne | |

Hornepayne | |

| Coordinates: 49°13′N 84°47′W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| District | Algoma |

| Established | 1915 |

| Incorporated | 1927 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Township |

| • Mayor | Cheryl T. Fort |

| • Federal riding | Algoma—Manitoulin—Kapuskasing |

| • Prov. riding | Algoma—Manitoulin |

| Area | |

| • Land | 204.52 km2 (78.97 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

| • Total | 980 |

| • Density | 4.8/km2 (12/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Postal Code | P0M |

| Area code(s) | 807 |

| Highways | |

| Website | www.townshipofhornepayne.ca |

History

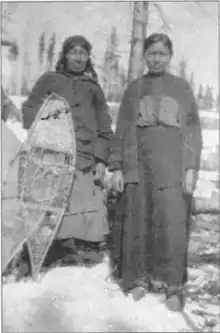

Indigenous First Nations people have lived in the area for centuries, as indicated by archaeological evidence such as potsherd fragments.[4] These are concentrated in the areas around Lake Nagagamisis, which is 30 kilometres (19 mi) to the north of Hornepayne, as well as the Shekak River to the west, rather than near Hornepayne itself, which before the arrival of the railway was largely remote and uninhabited.[3]:87 In the 19th century, they became involved in the fur trade and the mercantile activities of the Hudson's Bay Company.[4] By the early 1900s, they consisted of three Cree families living at Lake Nagagamisis, along with a number of Ojibwe who were possibly originally from Heron Bay.[3]:87 With the opening of the railway, they abandoned their existing trading post on Lake Nagagamisis in 1926 for a new settlement on Shekak Lake, which was closer to the rail line.[3]:87 By the 1940s, many of them had moved to Hornepayne to work in the railway and timber industries based in the town.[4] A number of their descendants are members of the Hornepayne First Nation, a member organization of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation.

Hornepayne differs from a number of older Northern Ontario settlements due to its distance from major waterways, making it relatively inaccessible before the advent of rail transportation in the north.[3]:87 The townsite was originally surveyed in 1877, when possible routes for the Canadian Pacific Railway transcontinental mainline were being explored.[3]:87 Instead of Canadian Pacific, however, Hornepayne would become associated with the Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR), one of several railways which were later amalgamated into the Canadian National Railways (CN) system during the 20th century. The Canadian Northern built its line through the area in 1915 and established a divisional point on the line called Fitzback. In 1919, the Canadian Northern was amalgamated into the Canadian National system. A year later, in 1920, the point was renamed Hornepayne, after the railway financier Robert Montgomery Horne-Payne.[3]:87

In the steam era, the railway system was labour-intensive and required many workers for maintenance of way, crew changes, and to resupply trains with coal and water at fixed intervals. This circumstance fostered the growth of "railway towns", as railway workers began to create permanent settlements to live in with their families. Sections of track were broken up into subdivisions, which were approximately 200 kilometres (120 mi) long and were separated by divisional points. Divisional points acted as a sort of local "headquarters" for the railways, and were very important for their operations. Additionally, most steam trains needed to be resupplied with coal at least once and water at least three times when passing through each subdivision, requiring railways to maintain even more permanent or semi-permanent settlements to support these operations. Hornepayne, as a divisional point, sat at the joining place between the CN Oba Subdivision (east to Foleyet) and the CN Caramat Subdivision (west to Nakina).[3]:78

Hornepayne initially had few permanent structures aside from the railway station, but was inhabited mostly by railway workers, who were young and well-paid for the era. A one-room schoolhouse was constructed in 1921 at the corner of First and Front streets, partially replacing the railway coach which was previously used as a school, though senior students were shifted to the old railway station. A new railway station, which was demolished in 2020, was also constructed in 1921. The situation was resolved when town ratepayers authorized $30,000 be spent on the construction of a new four-room school in the winter of 1923.[3]:88

Throughout the 1920s, Hornepayne grew, and soon was home to several grocery and general stores, as well as a butcher shop, a dress shop, a pharmacy, a Hudson's Bay Company store, two barbershops, a town hall, two restaurants, a bowling alley, two pool halls, and two hotels, one of which was owned by CN and one of which was independent.[3]:88 The town lacked in fresh fruit and vegetables early on, which were imported by rail from Port Arthur. Later, two farms, one of which was a dairy farm, were established in the area to feed the town. By the 1930s, one farm had around four hundred chickens.[3]:89 Due to its remote location, household electricity was slow to arrive in Hornepayne. Diesel-generated power was available from CN for most of the town starting in the 1930s, but the town would only be connected with the Ontario electrical grid in 1962.[3]:89

The town was incorporated in 1927–28 by local petition, and was poised to become a regional centre. A series of devastating fires in 1929–31, however, destroyed many of the town's commercial buildings, as well as the CNR shops. Rail traffic slowed during the Great Depression, and the town struggled, with some residents finding employment on highway construction under government public works funding.[3]:90 This difficult and slow work culminated in the opening of the northern section of Highway 631 in 1959, linking Hornepayne with Highway 11. In 1973, the highway was extended to the south to connect to Highway 17 at White River.[3]:91

In the 1970s and 1980s, Hornepayne underwent a considerable redevelopment push, spurring the southern highway extension, the opening of the Hornepayne Municipal Airport, and the creation of the mixed use Hallmark Centre "mall", merging together a number of commercial, recreational, and institutional aspects of the town. At various times, it included residences for CN temporary workers (an evolution of the CN bunkhouses which were demolished in the 1950s), a post office, the local high school, a hotel, a library, a swimming pool, a gym, apartments, and a Hudson's Bay Company department store. Many existing businesses relocated to the complex, though some remained at their old locations.[3]:92 Over the years, the complex became less and less commercially viable, and closed entirely in 2011.

Geography

Geology

Hornepayne is situated in the Horseshoe of Rock, which forms the Pre-Cambrian area, which surrounds Hudson Bay. It is the oldest rock in the world, containing the famous Keewatin Greenstone. Massive Granite intrusions, of which Tank Hill to is a good example, is the predominate rock in the area.

Greenstone can be found six miles north along highway 631 and in numerous bands along Government Lake Road. Volcanoes were numerous, and specimens of their eruptions in the soil today. The Pre-Cambrian was covered by at least three Ice Ages which, with glaciers miles high, bulldozed the mountains away just as a bulldozer today would level a small hill. The rock and earth were moved as far south as Wisconsin.

Evidence of glacial scratches can be found on Tank Hill. The sand hills near Cedar Point are eskers left by the Glaciers. Boulders, small rocks, and clay, are scattered throughout the area, part of the glacial wash. A typical volcanic core is to be found about five miles north. The highway runs through it. Samples of volcanics, such as garnets, serpentine, and rhyolite, can be found. Most of the Pre-Cambrian is covered by a thin layer of organic soil and clay. Hornepayne is approximately eight miles north of the height of land. Drainage is poor in the area, which has many muskeg swamps.

Climate

Hornepayne experiences a unique subarctic microclimate (Dfc) due to its elevation of 336 meters (1,101 feet) and location in Northern Ontario. Winters are long, snowy, and very cold for Ontario. Summers are generally warm with cool nights. Winter usually begins around Halloween, lasting through March, into April, though wintry days can sometimes be experienced even later in the season. Snowfall is abundant, starting to fall usually sometime in October, and keeps falling into April, with snowfalls in May not uncommon. Hornepayne is one of the driest communities in Ontario, receiving only 656.4 mm (25.84 inches) of precipitation falling on only 105.5 days.[5]

| Climate data for Hornepayne, Ontario (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 6.7 (44.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

37.2 (99.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

37.2 (99.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −13.1 (8.4) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

6.8 (44.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −19.7 (−3.5) |

−16 (3) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

0.4 (32.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−14.5 (5.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −26.1 (−15.0) |

−22.7 (−8.9) |

−15.7 (3.7) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

1.5 (34.7) |

5.7 (42.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−20.3 (−4.5) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −49.4 (−56.9) |

−52.2 (−62.0) |

−43.9 (−47.0) |

−37.2 (−35.0) |

−15 (5) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

−40 (−40) |

−52.2 (−62.0) |

−52.2 (−62.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 53.4 (2.10) |

38.5 (1.52) |

38.9 (1.53) |

28.7 (1.13) |

51.4 (2.02) |

81.5 (3.21) |

65.4 (2.57) |

67.2 (2.65) |

70.3 (2.77) |

60.8 (2.39) |

49.3 (1.94) |

51.0 (2.01) |

656.4 (25.84) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.1 (0.00) |

1.6 (0.06) |

3.9 (0.15) |

11.1 (0.44) |

45.3 (1.78) |

81.5 (3.21) |

65.4 (2.57) |

67.2 (2.65) |

69.4 (2.73) |

48.9 (1.93) |

15.1 (0.59) |

0.9 (0.04) |

410.5 (16.16) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 53.3 (21.0) |

36.9 (14.5) |

35.0 (13.8) |

17.6 (6.9) |

6.1 (2.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.9 (0.4) |

12.6 (5.0) |

34.3 (13.5) |

50.1 (19.7) |

246.7 (97.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8.6 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 5.9 | 7.3 | 9.2 | 8.6 | 9.4 | 12.9 | 10.9 | 9.2 | 9.4 | 105.5 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.12 | 0.38 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 6.5 | 9.2 | 8.6 | 9.4 | 12.8 | 8.6 | 2.6 | 0.41 | 62.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 8.5 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.22 | 2.9 | 7.1 | 9.3 | 45.7 |

| Source: Environment Canada[6] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Canada census – Hornepayne community profile | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2011 | 2006 | |

| Population: | 980 (-6.7% from 2011) | 1,050 (-13.2% from 2006) | 1,209 (-11.2% from 2001) |

| Land area: | 204.07 km2 (78.79 sq mi) | 204.52 km2 (78.97 sq mi) | 204.52 km2 (78.97 sq mi) |

| Population density: | 4.8/km2 (12/sq mi) | 5.1/km2 (13/sq mi) | 5.9/km2 (15/sq mi) |

| Median age: | 42.9 (M: 43.1, F: 42.4) | 41.2 (M: 41.0, F: 41.5) | 38.6 (M: 39.5, F: 38.1) |

| Total private dwellings: | 514 | 518 | 539 |

| Median household income: | $99,584 | $68,217 | |

| References: 2016[7] 2011[8] 2006[9] earlier[10] | |||

Population:[11]

- Population in 2011: 1,050

- Population in 2006: 1,209

- Population in 2001: 1,362

- Population in 1996: 1,480

- Population in 1991: 1,610

Mother tongue:[12]* English as first language: 78.3%

- French as first language: 16.3%

- English and French as first language: 0%

- Other as first language: 5.4%

Economy

Hornepayne serves as a railway divisional point on the main Canadian National Railway line. The forestry industry (by way of Haavaldsrud's Timber Company[13]) is the major employer to the local economy. Hunting- and fishing-related tourism in the area (particularly just north of the town in nearby Nagagami Lake Provincial Park) is served by several small companies.[14][15][16]

The township of Hornepayne has been the proposed site of a low level nuclear waste storage facility for some time. The town's community liaison group chose to withdraw from this development in the early 1990s,[17] but as of May 2010 the township is still being considered for nuclear waste management/storage.[18]

Transportation

Highway 631 runs through Hornepayne, connecting it to Highway 11 in the north and Highway 17 at White River in the south, both of which are part of the Trans-Canada Highway system.

Hornepayne is served by the Canadian, Canada's transcontinental passenger rail service, which is operated by Via Rail and which stops at Hornepayne station. The rail line through the town is part of the Canadian National Railway, and was originally constructed by the Canadian Northern Railway in 1915.[3]:87 Hornepayne is a divisional point on the railway, marking the point where two rail subdivisions join with each other: the CN Caramat Subdivision to the west (ending at Nakina) and the CN Ruel Subdivision.[3]:78

The town is also home to the Hornepayne Municipal Airport.

The CN rail yard; the old station in the background had been abandoned and was demolished in 2020. |

Passengers milling around the train at the station stop in Hornepayne. |

Popular culture

- Retired ice hockey player Mike McEwen was born in Hornepayne.

- Retired ice hockey player Goldie Goldthorpe (who served as the inspiration for Ogie Ogilthorpe in the 1977 film Slap Shot) was born in Hornepayne.

- Senior Vice President of Hockey Operations for NHL Kris King, was raised in Hornepayne.

- Gordon Lightfoot's song "On the High Seas" mentions Hornepayne with the following lyric "Was it up in Hornepayne, where the trains run on time?"

- Hornepayne was featured on an episode of Survivorman with Les Stroud and a slew of NHL hockey players.

See also

References

- "Hornepayne census profile". 2016 Census of Population. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- Roy, Patricia. "Robert Montgomery Horne-Payne". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- Douglas, Dan (1995). Northern Algoma: A People's History. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55002-235-0.

- "History". Hornepayne First Nation. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- "Hornepayne, Ontario, Canada Weather Forecast and Conditions - The Weather Channel | Weather.com". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- "Hornepayne, Ontario". Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000. Environment Canada. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- "2016 Community Profiles". 2016 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. February 21, 2017. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- "2011 Community Profiles". 2011 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. July 5, 2013. Retrieved 2012-02-16.

- "2006 Community Profiles". 2006 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. March 30, 2011. Retrieved 2012-02-16.

- "2001 Community Profiles". 2001 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. February 17, 2012.

- Statistics Canada: 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011 census

- Statistics Canada 2006 Census

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2011-09-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.pronorthoutfitters.com/

- http://flyinfishingcamps.com/

- http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/73397/1/j.1754-7121.1994.tb00885.x.pdf

- http://www.nwmo.ca/uploads_managed/MediaFiles/1797_hornepayne-summaryreport.pdf