Igorot people

The Igorot (Tagalog for 'mountaineer'), or ethnolinguistic groups in the Cordilleras, are any of various ethnic groups in the mountains of northern Luzon, Philippines, all of whom keep or have kept until recently, their traditional religion and way of life. Some live in the tropical forests of the foothills, but most live in rugged grassland and pine forest zones higher up. The Igorot numbered about 1.5 million in the early 21st century. Their languages belong to the northern Luzon subgroup of the Philippine languages, which belong to the Austronesian (Malayo-Polynesian) family. There are nine main ethnolinguistic groups in the Cordilleras. The Cordillera Administrative Region is located in Luzon and is the largest region in the Philippines.

A group of elderly Igorots. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,500,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(Cordillera Administrative Region, Ilocos Region, Cagayan Valley) | |

| Languages | |

| Bontoc, Ilocano, Itneg, Ibaloi, Isnag, Kankanaey, Bugkalot language | |

| Religion | |

| Animism (Indigenous Philippine folk religions), Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Episcopalianism, other Protestant sects) |

Etymology

From the root word golot, which means "mountain", Igolot means "people from the mountains" (Tagalog: “Mountaineer”), a reference to any of various ethnic groups in the mountains of northern Luzon. During the Spanish colonial era, the term was variously recorded as Igolot, Ygolot, and Igorrote, compliant to Spanish orthography.[2]

The endonyms Ifugao or Ipugaw (also meaning "mountain people") are used more frequently by the Igorots themselves, as igorot is viewed by some as slightly pejorative,[3] except by the Ibaloys.[4] The Spanish borrowed the term Ifugao from the lowland Gaddang and Ibanag groups.[3]

Cordillera ethnic groups

The Igorots may be roughly divided into two general subgroups: the larger group lives in the south, central and western areas, and is very adept at rice-terrace farming; the smaller group lives in the east and north. Prior to Spanish colonisation of the islands, the peoples now included under the term did not consider themselves as belonging to a single, cohesive ethnic group.[3]

Bontoc

_(14579727919).jpg.webp)

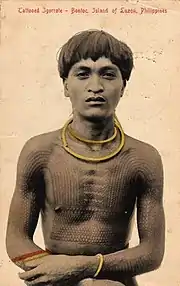

The Bontok ethnolinguistic group can be found in the central and east portions of the Mountain Province. It mainly consists of the Balangaos and Gaddangs, with a significant portion who identify as part of the Kalinga group. The Bontok live in a mountainous territory, particularly close to the Chico River and its tributaries. Mineral resources (gold, copper, limestone, gypsum) can be found in the mountain areas. Gold, in particular, has been traditionally extracted from the Bontoc municipality. The Chico River provides sand, gravel, and white clay, while the forests of Barlig and Sadanga within the area have rattan, bamboo and pine trees.[5] They are the second largest group in the Mountain Province.[5] The Bontoc live on the banks of the Chico River. They speak Bontoc and Ilocano. They formerly practiced head-hunting and had distinctive body tattoos. The Bontoc describe three types of tattoos: The chak-lag′, the tattooed chest of the head taker; pong′-o, the tattooed arms of men and women; and fa′-tĕk, for all other tattoos of both sexes. Women were tattooed on the arms only.

In the past, the Bontoc engaged in none of the usual pastimes or games of chance practiced in other areas of the country but did perform a circular rhythmic dance acting out certain aspects of the hunt, always accompanied by the gang′-sa or bronze gong. There was no singing or talking during the dance drama, but the women took part, usually outside the circumference. It was a serious but pleasurable event for all concerned, including the children.[6] Present-day Bontocs are a peaceful agricultural people who have, by choice, retained most of their traditional culture despite frequent contacts with other groups. Music is also important to Bontoc life, and is usually played during ceremonies. Songs and chants are accompanied by nose flutes (lalaleng), gongs (gangsa), bamboo mouth organ (affiliao), and Jew's harp (ab-a-fiw). Wealthy families make use of jewelry, which are commonly made of gold, glass beads, agate beads (appong), or shells, to show their status.[5]

The pre-Christian Bontoc belief system centers on a hierarchy of spirits, the highest being a supreme deity called Intutungcho, whose son, Lumawig, descended from the sky (chayya), to marry a Bontoc girl. Lumawig taught the Bontoc their arts and skills, including irrigation of their land. The Bontoc also believe in the anito, spirits of the dead, who are omnipresent and must be constantly consoled. Anyone can invoke the anito, but a seer (insup-ok) intercedes when someone is sick through evil spirits.[5]

The Bontok hero Lumawig instituted their ator, a political institution identified with a ceremonial place adorned with headhunting skulls. Lumawig also gave the Bontok their irrigation skills, Taboos, rituals, and ceremonies after he descended from the sky (chayya) and married a Bontok girl. Each ator has a council of elders, called ingtugtukon, who are experts in custom laws (adat). Decisions are by consensus.[5]

_(14579912297).jpg.webp)

The Bontoc social structure used to be centered around village wards containing about 14 to 50 homes. Traditionally, young men and women lived in dormitories and ate meals with their families. This gradually changed with the advent of Christianity. Bontoks have three different indigenous housing structures: the residence place of the family (katyufong), the dormitories for females (olog), and the dormitories for males (ato/ator). Different structures are mostly associated with agricultural needs, such as rice granaries (akhamang) and pigpens (khongo). Traditionally, all structures have inatep, cogon grass roofs. Bontok houses also have numerous utensils, tools, and weapons: like cooking tools; agricultural tools like bolos, trowels, and plows, bamboo or rattan fish traps. Weapons include battleaxes (pin-nang/pinangas), knives and spears (falfeg, fangkao, sinalawitan), and shields (kalasag).[5]

The Bontok take pride in their kinship ties and oneness as a group (sinpangili) based on affiliations, history together against intruders, and community rituals for agriculture and matters which affect the entire province, like natural disasters. Kinship groups have two main functions: controlling property and regulating marriage. However, they are also important for the mutual cooperation of the group's members.[5]

There are generally three social classes in Bontok society, the kakachangyan (rich), the wad-ay ngachanna (middle-class), and the lawa (poor). The rich sponsor feasts, and assist those in distress, as a demonstration of their wealth. The poor usually work as sharecroppers or as laborers for the rich.[5]

Men wear g-strings (wanes) and a rattan cap (suklong). Women wear skirts (tapis).[5]

Ibaloi

The Ibaloi (also Ibaloi, Ibaluy, Nabaloi, Inavidoy, Inibaloi, Ivadoy) and Kalanguya (also Kallahan and Ikalahan) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Philippines who live mostly in the southern part of Benguet, located in the Cordillera of northern Luzon, and Nueva Vizcaya in the Cagayan Valley region. They were traditionally an agrarian society. Many of the Ibaloi and Kalanguya people continue with their agriculture and rice cultivation.

Their native language belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian languages family and is closely related to the Pangasinan language, primarily spoken in the province of Pangasinan, located southwest of Benguet.

Baguio, the major city of the Cordillera, dubbed the "Summer Capital of the Philippines," is located in southern Benguet.

The largest feast of the Ibaloi is the Peshit or Pedit, a public feast mainly sponsored by people of prestige and wealth. Peshit can last for weeks and involves the killing and sacrifice of dozens of animals.

One of the more popular dances of the Ibaloi is the bendian, a mass dance participated in by hundreds of male and female dancers. Originally a victory dance in time of war, it evolved into a celebratory dance. It is used as entertainment (ad-adivay) in the cañao feasts, hosted by the wealthy class (baknang).[7]

Ifugao

Ifugaos, commonly known as Igorots in Filipino, are the people inhabiting Ifugao Province. They come from the municipalities of Lagawe (Capital Town), Aguinaldo, Alfonso Lista, Asipulo, Banaue, Hingyon, Hungduan, Kiangan, Lamut, Mayoyao, and Tinoc. The province is one of the smallest provinces in the Philippines with an area of only 251,778 hectares, or about 0.8% of the total Philippine land area. It has a temperate climate and is rich in mineral and forest products.[8]

The term "Ifugao" is derived from "ipugo" which means "earth people", "mortals" or "humans", as distinguished from spirits and deities. It also means "from the hill", as pugo means hill.[8] The term Igorot or Ygolote was the term used by Spanish conquerors for mountain people. The Ifugaos, however, prefer the name Ifugao.

Although a majority of them already converted to Roman Catholic from their original animistic religion, from their mythology, they believed that they descended from Wigan and Bugan, who are the children of Bakkayawan and Bugan of the Skyworld (Kabunyan). Henry Otley Beyer thought the Ifugaos originated from Indo-China 2,000 years ago. Felix Keesing thought they came from the Magat area because of the Spanish, hence the rice terraces are only a few hundred years old. The Ifugao popular epic, The Hudhud of Dinulawan and Bugan of Gonhadan supports this interpretation. Dulawan thought the Ifugaos came from the western Mountain Province due to similarities with Kankana-eys culture and language.[8]

Wet rice terraces characterize their farming, supplemented with swidden farming of camote.[8] They are famous for their Banaue Rice Terraces, which became one of the main tourist attractions in the country.

The Ifuago are known for their rich oral literary traditions of hudhud and the alim. In 2001, the Hudhud Chants of the Ifugao was chosen as one of the 11 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. It was then formally inscribed as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2008.

The Ifugao language consists of four dialects. Due to being isolated by the terrain, Ifugaos usually speak in English and Ilocano as their alternative to their mother tongue. Most Ifugaos are fluent in Filipino/Tagalog.

The Ifugaos’ highest prestige feasts are the hagabi, sponsored by the elite (kadangyan); and the uyauy, a marriage feast sponsored by those immediately below the wealthiest (inmuy-ya-uy). The middle class are the tagu, while the poor are the nawotwot.[8]

As of 1995, the population of the Ifugaos was counted to be 131,635. Although the majority of them are still in Ifugao province, some of them already transferred to Baguio, where they worked as woodcarvers, and to other parts of the Cordillera region.[8] They are divided into subgroups based on the differences in dialects, traditions, and design/color of costumes. The main subgroups are Ayangan, Kalangaya, and Tuwali. Furthermore, the Ifugao society is divided into 3 social classes: the kadangyans or the aristocrats, the tagus or the middle class, and the nawotwots or the poor ones. The kadangyans sponsor the prestige rituals called hagabi and uyauy and this separates them from the tagus who cannot sponsor feasts but are economically well off. The nawotwots are those who have limited land properties and are usually hired by the upper classes to do work in the fields and other services.[8]

The Ifugaos host a number of similarities with the Bontocs in terms of agriculture, but the Ifugao tend to have more scattered settlements, and recognize their affiliation mostly towards direct kin in households closer to their fields [9]

From a person's birth to his death, the Ifugaos follow a lot of traditions. Pahang and palat di oban are performed to a mother to ensure safe delivery. After delivery, no visitors are allowed to enter the house until among is performed when the baby is given a name. Kolot and balihong are then performed to ensure the health and good characteristics of the boy or the girl, respectively. As they grow older, they sleep in exclusive dormitories because it is considered indecent for siblings of different genders to sleep in the same house. The men are the ones who hunt, recite myths, and work in the fields. Women also work in the fields, aside from managing the homes and reciting ballads. Betrothals are also common, especially among the wealthy class; and like other Filipinos, they perform several customs in marriage like bubun (providing a pig to the woman's family). Lastly, the Ifugaos do not mourn for the elderly who died, nor for the baby or the mother who died in a conception. This is to prevent the same event from happening again in the family. Also, the Ifugaos believe in life after death so those who are murdered are given a ritual called opa to force their souls into the place where his ancestors dwell.[8]

Ifugao houses (Bale) are built on four wooden posts 3 meters from the ground, and consist of one room, a front door (panto) and back door (awidan), with a detachable ladder (tete) to the front door. Temporary huts (abong) give shelter to workers in the field or forest. Rice granaries (alang) are protected by a wooden guardian (bulul).[8]

Men wear a loincloth (wanoh) while women wear a skirt (ampuyo). On special occasions, men wear a betel bag (pinuhha) and their bolo (gimbattan). Musical instruments include gongfs (gangha), a wooden instrument that is struck with another piece of wood (bangibang), a thin brass instrument that is plucked (bikkung), stringed instruments (ayyuding and babbong), nose flutes (ingngiing) and mouth flutes (kupliing or ippiip).[8]

Criminal cases are tried by ordeal. They include duels (uggub/alao), wrestling (bultong), hot bolo ordeal and boiling water ordeal (da-u). Ifugaos believe in 6 worlds, Skyworld (Kabunyan), Earthworld (Pugaw), Underworld (Dalom), the Eastern World (Lagud), the Western World (Daya), and the Spiritual World (Kadungayan). Talikud carries the Earthworld on his shoulders and cause earthquakes. The ifugaos include nature and ancestor worship, and participate in rituals (baki) presided over by a mumbaki. Priests (munagao and mumbini) guide the people in rites for good fortune.[8]

Kalanguya/Ikalahan

The Kalaguya or Ikalahan people are a small group distributed amongst the mountain ranges of Sierra Madre, the Caraballo, and the eastern part of the Cordillera mountain range. The main population resides in the Nueva Vizcaya province, with Kayapa as the center. They are considered to be part of the Igorot (mountain people) but distinguish themselves with the name Ikalahan, the name taken from the forest trees that grow in the Caraballo Mountain.[10]

They are among the least studied ethnic groups, thus their early history is unknown. However, Felix M. Keesing suggests that, like other groups in the mountains, they fled from the lowlands to escape Spanish persecution.[10]

There are two classes of society, the rich (baknang or Kadangyan) and the poor (biteg or abiteng). Ikalahan practice swidden (“slash-and-burn”) farming (inum-an) of camote, and yam (gabi).[10]

Ikalahan houses, traditionally made for one nuclear family, have of reeds (pal-ot) or cogon (gulon) for roofs, barks or slabs of trees for the walls, and palm strips (balagnot) for the floor. The houses are traditionally rectangular and raised from the ground 3–5 feet, with one main room for general activities and one window and door. There is usually a separate room (duwag) for visitors or single family members only, opposite the kitchen area. Two stone stoves are on a hearth, one cooks meals for the pigs in a copper cauldron (gambang), the other for the household. Shelves (pagyay) keep household utensils, including wooden bowls (duyo) and camote trays (ballikan or tallaka) made of rattan. Camote peelings (dahdah) or rejects (padiw) are fed to the pigs, which are herded under the living area or in a sty near the house.[10]

The Ikalahan, like many ethnic groups, enjoy using musical instruments in celebration, most of which are made out of bamboo. Gongs (gangha) are the primary instruments used, and are complemented by drums. They also use a native guitar, or galdang, and a vibrating instrument called the pakgong played by striking, besides the Jew's harp (Ko-ling).[10]

For clothing, Ikalahan men wear a loincloth or G-string (kubal), and carry backpacks (akbot) made out of deer hide. Men almost always carry a bolo when leaving the house. Women wear woven skirts (lakba) around the waist, made up of flaps of different color combinations. They wear a blouse from the same material. They use a basket (kayabang) carried on the back for carrying their farming tools. Body ornaments include brass coiled bracelets (gading or batling).[10]

Society authority rests with the elders (nangkaama), with the tongtongan conference being the final say in matters. Feats include the keleng for healing the sick, ancestor remembrance, and other occasions. A sponsor may also hold a ten-day feast, padit.[10]

Isneg

The Isnag, also Isneg or Apayao, live at the northwesterly end of northern Luzon, in the upper half of the Cordillera province of Apayao. The term "Isneg" derives from itneg, meaning inhabitants of the Tineg River. Apayao derives from the battle cry Ma-ap-ay-ao as their hand is clapped rapidly over their mouth. They may also refer to themselves as Imandaya if they live upstream, or Imallod if they live downstream. The municipalities in the Isneg domain include Pudtol, Kabugao, Calanasan, Flora, Conner, Sta. Marcela, and Luna. Two major river systems, the Abulog River and the Apayao River, run through Isnag country.[11]

Jars of basi are half-buried in the ground within a small shed, abulor, constructed of 4 posts and a shed. This abulor is found within the open space, linong or sidong, below their houses (balay). They grow upland rice, while also practicing swidden farming and fishing.[11]:99–100,102

Say-am was an important ceremony after a successful headhunting, or other important occasions, hosted by the wealthy, and lasting one to five days or more. Dancing, singing, eating, and drinking mark the feast, and Isnegs wear their finest clothes. The shaman, Anituwan, prays to the spirit Gatan, before the first dog is sacrificed, if a human head had not been taken, and offered at the sacred tree, ammadingan. On the last day, a coconut is split in honor of the headhunter guardian, Anglabbang.The Pildap is an equivalent say-am but hosted by the poor. Conversion to Christianity grew after 1920, and today, the Isnegs are divided in their religious beliefs, with some still being animistic.[11]:107–108,110–111,113

Itneg/Tingguian

The Itneg people, also known as Tingguian people, live in the mountainous area of Abra in northwestern Luzon who descended from immigrants from Kalinga, Apayao, and the Northern Kankana-ey. They are large in stature, have mongoloid eyes, aquiline nose, and are effective farmers. They refer to themselves as Itneg, though the Spaniards called them Tingguian when they came to the Philippines because they are mountain dwellers. The Tingguians are further divided into nine distinct subgroups which are the Adasen, Mabaka, Gubang, Banao, Binongon, Danak, Moyodan, Dawangan, and Ilaud. Wealth and material possessions (such as Chinese jars, copper gongs called gangsa, beads, rice fields, and livestock) determine the social standing of a family or person, as well as the hosting of feasts and ceremonies. Despite the divide of social status, there is no sharp distinction between rich (baknang) and poor. Wealth is inherited but the society is open for social mobility of the citizens by virtue of hard work. Medium are the only distinct group in their society, but even then it is only during ceremonial periods.[12]

Kalinga

The Kalingas are mainly found in Kalinga province which has an area of 3,282.58 sq. km. Some of them, however, already migrated to Mountain Province, Apayao, Cagayan, and Abra. As of 1995, they were counted to be 105,083, not including those who have migrated outside the Cordillera region.[13]

Kalinga territory includes floodplains of Tabuk, and Rizal, plus the Chico River. Gold and copper deposits are common in Pasil and Balbalan. Tabuk was settled in the 12th century, and from there other Kalinga settlements spread, practicing wet rice (papayaw) and swidden (uwa) cultivation. Kalinga houses (furoy, buloy, fuloy, phoyoy, biloy)are either octagonal for the wealthy, or square, and are elevated on posts (a few as high as 20–30 feet), with a single room. Other building include granaries (alang) and field sheds (sigay).[13][14]

The name Kalinga came from the Ibanag and Gaddang term kalinga, which means headhunter. Edward Dozier divided Kalinga geographically into three sub-cultures and geographical position: Balbalan (north); Pasil, Lubuagan, and Tinglayan (south); and Tanudan (east). Teodoro Llamzon divided the Kalinga based on their dialects: Guinaang, Lubuagan, Punukpuk, Tabuk, Tinglayan, and Tanudan.[13]

Like other ethnic groups, families and kinship systems are also important in the social organizations of Kalingas. They are, however, stratified into two economic classes only which are determined by the number of their rice fields, working animals, and heirlooms: the kapos (poor) and the baknang (wealthy). The wealthy employ servants (poyong). Politically, the mingol and the papangat have the highest status. The mingols are those who have killed many in headhunting and the papangats are those former mingols who assumed leadership after the disappearance of headhunting. They are usually the peacemakers, and the people ask advice from them, so it is important that they are wise and have good oratorical ability. The Kalinga developed an institution of peace pacts called Bodong which has minimised traditional warfare and headhunting and serves as a mechanism for the initiation, maintenance, renewal, and reinforcement of kinship and social ties.[13]

Like the other ethnic groups, they also follow a lot of customs and traditions. For example, pregnant women and their husbands are not allowed to eat beef, cow’s milk, and dog meat. They must also avoid streams and waterfalls as these cause harm to unborn children. Other notable traditions are the ngilin (avoiding the evil water spirit) and the kontad or kontid (ritual performed to the child to avoid harms in the future). Betrothals are also common, even as early as birth, but one may break this engagement if he/she is not in favour of it. Upon death, sacrifices are also made in honour of the spirit of the dead and kolias is celebrated after one year of mourning period.[13]

They use the uniquely shaped Kalinga head ax (sinawit), bolo (gaman/badang), spears (balbog/tubay/say-ang), and shields (kalasag). They also carry a rattan backpack (pasiking) and betel nut bag (buyo).[13]

Kalinga men wear ba-ag (loincloths) while the women wear saya (colourful garment covering the waist down to the feet). The women are also tattooed on their arms up to their shoulders and wear colourful ornaments like bracelets, earrings, and necklaces, especially on the day of festivities. Heirlooms include Chinese plates (panay), jars (gosi), and gongs (gangsa). Key dances include the courtship dance (salidsid) and war dance (pala-ok or pattong).[13]

The Kalinga belief in a Supreme Being, Kabuniyan, the creator and giver of life, who once lived amongst them. They also believe in numerous spirits and deities, including those associated with nature (pinaing and aran), and dead ancestors (kakarading and anani). The priestess (manganito, mandadawak, or mangalisig) communicate with these spirits.[13]

Kankanaey

.jpg.webp)

The Kankanaey domain includes Western Mountain Province, northern Benguet and southeastern Ilocos Sur. Like most Igorot ethnic groups, the Kankanaey built sloping terraces to maximize farm space in the rugged terrain of the Cordilleras.

Kankanaey houses include the two-story innagamang, the larger binangi, the cheaper tinokbob, and the elevated tinabla. Their granaries (agamang) are elevated to avoid rats. Two other institutions of the Kankanaey of Mountain Province are the dap-ay, or the men's dormitory and civic center, and the ebgan, or the girls' dormitory.[15][16]

Kankanaey's major dances include tayaw, pat-tong, takik (a wedding dance), and balangbang. The tayaw is a community dance that is usually done in weddings it maybe also danced by the Ibaloi but has a different style. Pattong, also a community dance from Mountain Province which every municipality has its own style, while Balangbang is the dance's modern term. There are also some other dances like the sakkuting, pinanyuan (another wedding dance) and bogi-bogi (courtship dance).

Northern Kankanaey

The Northern Kankanaey live in Sagada and Besao, west of Mountain province, and constitute a linguistic group. They are referred to with the generic name Igorot, but call themselves Aplai. H. Otley Beyer believed they originated from a migrating group from Asia who landed on the coasts of Pangasinan before moving to Cordillera. Beyer's theory has since been discredited, and Felix Keesing speculated the people were simply evading the Spanish. Their smallest social unit is the sinba-ey, which includes the father, mother, and children. The sinba-eys make up the dap-ay/ebgan which is the ward. Their society is divided into two classes: the kadangyan (rich), who are the leaders and who inherit their power through lineage or intermarriage, and the kado (poor). They practice bilateral kinship.[15]

The Northern Kankana-eys believe in many supernatural beliefs and omens, and in gods and spirits like the anito (soul of the dead) and nature spirits.[15]

They also have various rituals, such as the rituals for courtship and marriage and death and burial. The courtship and marriage process of the Northern Kankana-eys starts with the man visiting the woman of his choice and singing (day-eng), or serenading her using an awiding (harp), panpipe (diw-as), or a nose flute (kalelleng). If the parents agree to their marriage, they exchange work for a day (dok-ong and ob-obbo), i.e. the man brings logs or bundled firewood as a sign of his sincerity, the woman works on the man’s father’s field with a female friend. They then undergo the preliminary marriage ritual (pasya) and exchange food. Then comes the marriage celebration itself (dawak/bayas)inclusive of the segep (which means to enter), pakde (sacrifice), betbet (butchering of pig for omens), playog/kolay (marriage ceremony proper), tebyag (merrymaking), mensupot (gift giving), sekat di tawid (giving of inheritance), and buka/inga, the end of the celebration. The married couple cannot separate once a child is born, and adultery is forbidden in their society as it is believed to bring misfortune and illness upon the adulterer. On the other hand, the Northern Kankana-eys honor their dead by keeping vigil and performing the rituals sangbo (offering of 2 pigs and 3 chickens), baya-o (singing of a dirge by three men), menbaya-o (elegy) and sedey (offering of pig). They finish off the burial ritual with dedeg (song of the dead), and then, the sons and grandsons carry the body to its resting place.[15]

The Northern Kankana-eys have rich material culture among which is the four types of houses: the two-story inhagmang, binang-iyan, tinokbobo and the elevated tinabla. Other buildings include the granary (agamang), male clubhouse (dap-ay or abong), and female dormitory (ebgan). Their men wear rectangular woven cloths wrapped around their waist to cover the buttocks and the groin (wanes). The women wear native woven skirts (pingay or tapis) that cover their lower body from waist to knees and is held by a thick belt (bagket).[15]

Their household is sparsely furnished with only a bangkito/tokdowan, po-ok (small box for storage of rice and wine), clay pots, and sokong (carved bowl). Their baskets are made of woven rattan, bamboo or anes, and come in various shapes and sizes.[15]

The Kankana-eys have three main weapons, the bolo (gamig), the axe (wasay) and the spear (balbeg), which they previously used to kill with but now serve practical purposes in their livelihood. They also developed tools for more efficient ways of doing their work like the sagad (harrow), alado (plow dragged by carabao), sinowan, plus sanggap and kagitgit for digging. They also possess Chinese jars (gosi) and copper gongs (gangsa).[15]

For a living, the Northern Kankana-eys take part in barter and trade in kind, agriculture (usually on terraces), camote/sweet potato farming, slash-and-burn/swidden farming, hunting, fishing and food gathering, handicraft and other cottage industry. They have a simple political life, with the Dap-ay/abong being the center of all political, religious, and socials activities, with each dap-ay experiencing a certain degree of autonomy. The council of elders, known as the Amam-a, are a group of old, married men expert in custom law and lead in the decision-making for the village. They worship ancestors (anitos) and nature spirits.[15]

Southern Kankanaey

The Southern Kankanaey are one of the ethnolinguistic groups in the Cordillera. They live in the mountainous regions of Mountain Province and Benguet, more specifically in the municipalities of Tidian, Bauko, Sabangan, Bakun, Kibungan and Mankayan. They are predominantly a nuclear family type (sinbe-ey,buma-ey, or sinpangabong), which are either patri-local or matri-local due to their bilateral kinship, composed of the husband, wife and their children. The kinship group of the Southern Kankana-eys consists of his descent group and, once he is married, his affinal kinsmen. Their society is divided into two social classes based primarily on the ownership of land: The rich (baknang) and the poor (abiteg or kodo). The baknang are the primary landowners to whom the abiteg render their services to. The Mankayan Kankana-eys, however, has no clear distinction between the baknang and the abiteg and all have equal access to resources such as the copper and gold mines.[16]

Contrary to popular belief, the Southern Kankana-eys do not worship idols and images. The carved images in their homes only serve decorative purposes. They believe in the existence of deities, the highest among which is Adikaila of the Skyworld whom they believe created all things. Next in the hierarchy is the Kabunyan, who are the gods and goddesses of the Skyworld, including their teachers Lumawig and Kabigat. They also believe in the spirits of ancestors (ap-apo or kakkading), and the earth spirits they call anito. They are very superstitious and believe that performing rituals and ceremonies help deter misfortunes and calamities. Some of these rituals are pedit (to bring good luck to newlyweds), pasang (cure sterility and sleeping sickness, particularly drowsiness) and pakde (cleanse community from death-causing evil spirits).[16]

The Southern Kankana-eys have a long process for courtship and marriage which starts when the man makes his intentions of marrying the woman known to her. Next is the sabangan, when the couple makes their wish to marry known to their family. The man offers firewood to the father of the woman, while the woman offers firewood to the man’s father. The parents then talk about the terms of the marriage, including the bride price to be paid by the man’s family. On the day of the marriage, the relatives of both parties offer gifts to the couple, and a pig is butchered to have its bile inspected for omens which would show if they should go on with the wedding. The wedding day for the Southern Kankana-eys is an occasion for merrymaking and usually lasts until the next day. Though married, the bride and groom are not allowed to consummate their marriage and must remain separated until such a time that they move to their own separate home.[16]

The funeral ritual of the Southern Kankana-eys lasts up to ten days, when the family honors their dead by chanting dirges and vigils and sacrificing a pig for each day of the vigil. Five days after the burial of the dead, those who participated in the burial take a bath in a river together, butcher a chicken, then offer a prayer to the soul of the dead.[16]

The Southern Kankana-eys have different types of houses among which are binang-iyan (box-like compartment on 4 posts 5 feet high), apa or inalpa (a temporary shelter smaller than bingang-iyan), inalteb (has a gabled roof and shorter eaves allowing for the installation of windows and other opening at the side), allao (a temporary built in the fields), at-ato or dap-ay (a clubhouse or dormitory for men, with a long, low gable-roofed structure with only a single door for entrance and exit), and ''ebgang or olog (equivalent to the at-ato, but for women). Men traditionally wear a G-string (wanes) around the waist and between the legs which is tightened at the back. Both ends hang loose at the front and back to provide additional cover. Men also wear a woven blanket for an upper garment and sometimes a headband, usually colored red like the G-string. The women, on the other hand, wear a tapis, a skirt wrapped around to cover from the waist to the knees held together by a belt (bagket) or tucked in the upper edges usually color white with occasional dark blue color. As adornments, both men and women wear bead leglets, copper or shell earrings, and beads of copper coin. They also sport tattoos which serve as body ornaments and “garments”.[16]

Southern Kankana-eys are economically involved in hunting and foraging (their chief livelihood), wet rice and swidden farming, fishing, animal domestication, trade, mining, weaving and pottery in their day-to-day activities to meet their needs. The leadership structure is largely based on land ownership, thus the more well-off control the community's resources. The village elders (lallakay/dakay or amam-a) who act as arbiters and jurors have the duty to settlements between conflicting members of the community, facilitate discussion among the villagers concerning the welfare of the community and lead in the observance of rituals. They also practice trial by ordeal. Native priests (mansip-ok, manbunong, and mankotom) supervise rituals, read omens, heal the sick, and remember genealogies.[16]

Gold and copper mining is abundant in Mankayan. Ore veins are excavated, then crushed using a large flat stone (gai-dan). The gold is separated using a water trough (sabak and dayasan), then melted into gold cakes.[16]

Musical instruments include the tubular drum (solibao), brass or copper gongs (gangsa), Jew's harp (piwpiw), nose flute (kalaleng), and a bamboo-wood guitar (agaldang).[16]

There is no more pure Southern Kankana-ey culture because of culture change that modified the customs and traditions of the people. The socio-cultural changes are largely due to a combination of factors which include the change in the local government system when the Spaniards came, the introduction of Christianity, the education system that widened the perspective of the individuals of the community, and the encounters with different people and ways of life through trade and commerce.[16]

Ethnic groups by linguistic classification

Below is a list of northern Luzon ethnic groups organized by linguistic classification.

- Northern Luzon languages

- Ilokano (Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur)

- Northern Cordilleran

- Isneg (northern Apayao Province)

- Gaddang (Nueva Vizcaya Province and Isabela Province)

- Ibanagic

- Ibanag (Cagayan Province and Isabela Province)

- Itawis (southern Cagayan Province)

- Yogad (Isabela Province)

- Central Cordilleran

- Kalinga–Itneg

- Nuclear

- Ifugao (Ifugao Province)

- Balangao (eastern Mountain Province)

- Bontok (central Mountain Province)

- Kankanaey (western Mountain Province, northern Benguet Province)

- Southern Cordilleran

- Ibaloi (southern Benguet Province)

- Kalanguya/Kallahan (eastern Benguet Province, Ifugao Province, northwestern Nueva Vizcaya Province)[17]

- Karao (Karao, Bokod, Benguet)

- Ilongot (eastern Nueva Vizcaya Province, western Quirino Province)

- Pangasinan (Pangasinan Province)

History

The gold found in the land of the Igorot was an attraction for the Spanish.[21] Originally gold was exchanged at Pangasinan by the Igorot.[22] The gold was used to buy consumable products by the Igorot.[23] Both gold and desire to Christianize the Igorot were given as reasons for Spanish conquest.[24] In 1572 the Spanish started hunting for the gold.[25] Benguet Province was entered by the Spanish with the intention of obtaining gold.[26] The fact that the Igorots managed to stay out of Spanish dominion vexed the Spaniards.[27] The gold evaded the hands of the Spaniards due to Igorot opposition.[28]

Samuel E. Kane wrote about his life amongst the Bontoc, Ifugao, and Kalinga after the Philippine–American War, in his book Thirty Years with the Philippine Head-Hunters (1933).[29] The first American school for Igorot girls was opened in Baguio in 1901 by Alice McKay Kelly.[29]:317 Kane noted that Dean C. Worcester "did more than anyone man to stop head-hunting and to bring the traditional enemy tribes together in friendship."[29]:329 Kane wrote of the Igorot people, "there is a peace, a rhythm and an elemental strength in the life...which all the comforts and refinements of civilization can not replace...fifty years hence...there will be little left to remind the young Igorots of the days when the drums and ganzas of the head-hunting canyaos resounded throughout the land.[29]:330–331

In 1904, a group of Igorot people were brought to St. Louis, Missouri, United States for the St. Louis World's Fair. They constructed the Igorot Village in the Philippine Exposition section of the fair, which became one of the most popular exhibits. The poet T. S. Eliot, who was born and raised in St. Louis, visited and explored the Village. Inspired by their tribal dance and others, he wrote the short story, "The Man Who Was King" (1905).[30] In 1905, 50 tribespeople were on display at a Brooklyn, New York amusement park for the summer, ending in the custody of the unscrupulous Truman K. Hunt, a showman "on the run across America with the tribe in tow."[31]

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, Igorots fought against Japan. Donald Blackburn's World War II guerrilla force had a strong core of Igorots.[32]:148–165

In 2014, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, an indigenous rights advocate, of Igorot ethnicity, was appointed UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[33]

On February the 4th, 2021, a letter was written by Representative Maximo Y. Dalog, Jr of the lone district of Mountain Province, to the Philippine Department of Education Secretary Leonor Magtolis Briones, calling the agency to look into some books and learning modules allegedly made and published to discriminate and malign the Igorots. Examples of frustrations listed in the letter include descriptions of Igorots having dark and curly hair, looking differently to the other FIlipino peoples (in terms of fashion, attire), and capacity to finish a sound education. A reply came from the Department of Education through its Regional Director Estela L. Casino on Friday, sincerely apologising for making use of the Igorot tribe as example in the learning material. It acknowledged that various posts portraying Igorots in learning resources went viral on Facebook citing one material from another region which was immediately traced because the reference and author was captured. Carino said that when such was printed from one school, however, the copies were immediately retrieved when brought to the Department of Education’s attention. Director Carino also furthered that DepEd-CAR remains steadfast in its stand to rally against any form of prejudice. [34]

See also

References

- The Editors (2015-03-26). "Igorot | people". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- Albert Ernest Jenks (2004). The Bontoc Igorot (PDF). Kessinger Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4191-5449-2.

- Carol R. Ember; Melvin Ember (2003). Encyclopedia of sex and gender: men and women in the world's cultures, Volume 1. Springer. p. 498. ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6.

- Communication, UP College of Mass. "Ibaloys "Reclaiming" Baguio: The Role of Intellectuals". Plaridel Journal.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "1 The Bontoks". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 1–27. ISBN 9789711011093.

- "The Bontoc Igorot".

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "2 The Ibaloys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 28–51. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "4 The Ifugaos". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 71–91. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Goda, Toh (2001). Cordillera: Diversity in Culture Change, Social Anthropology of Hill People in Northern Luzon, Philippines. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "3 The Ikalahans". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 52–69. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "5 The Isnegs". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 92–93. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "9 The Tingguians/Itnegs". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 177–194. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "5 The Kalingas". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 115–135. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Scott, William Henry (1996). On the Cordilleras: A look at the peoples and cultures of the Mountain Province. 884 Nicanor Reyes, Manila, Philippines: MCS Enterprises, Inc. p. 16.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "7 The Northern Kankana-eys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 136–155. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "8 The Southern Kankana-eys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 156–175. ISBN 9789711011093.

- "Kalanguya Archives - Intercontinental Cry".

- "Kallahan, Keley-i".

- "Kalanguya".

- Project, Joshua. "Kalanguya, Tinoc in Philippines".

- Barbara A. West (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. pp. 300–. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- "Ifugao - Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life - Encyclopedia.com".

- Linda A. Newson (2009). Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-0-8248-3272-8.

- "Benguet mines, forever in resistance by the Igorots – Amianan Balita Ngayon".

- "Ethnic History (Cordillera) - National Commission for Culture and the Arts". ncca.gov.ph.

- Melanie Wiber (1993). Politics, Property and Law in the Philippine Uplands. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-0-88920-222-1.

igorot gold spanish.

- "The Igorot struggle for independence: William Henry Scott".

- Habana, Olivia M. (1 January 2000). "Gold Mining in Benguet to 1898". Philippine Studies. 48 (4): 455–487. JSTOR 42634423.

- Kane, S.E., 1933, Life and Death in Luzon or Thirty Years with the Philippine Head-Hunters, New York: Grosset & Dunlap

- Narita, Tatsushi. "How Far is T. S. Eliot from Here?: The Young Poet's Imagined World of Polynesian Matahiva," In How Far is America from Here?, ed. Theo D'haen, Paul Giles, Djelal Kadir and Lois Parkinson Zamora. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2005, pp .271-282.

- Prentice, Claire, 2014, The Lost Tribe of Coney Island: Headhunters, Luna Park, and the Man Who Pulled Off the Spectacle of the Century, New Harvest. The Lost Tribe of Coney Island: Product Details. October 14, 2014. ISBN 978-0544262287.

- Harkins, P., 1956, Blackburn's Headhunters, London: Cassell & Co. LTD

- James Anaya Victoria Tauli-Corpuz begins as new Special Rapporteur, 02 June 2014

- Ora (2021-02-05). "DepEd responds to Social Content Issues on learning materials about Igorots". Igorotage. Retrieved 2021-02-07.

Further reading

- Boeger, Astrid. 'St. Louis 1904'. In Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions, ed. John E. Findling and Kimberly D. Pelle. McFarland, 2008.

- Conklin, Harold C., Pugguwon Lupaih, Miklos Pinther, and the American Geographical Society of New York. (1980). American Geographical Society of New York (ed.). Ethnographic Atlas of Ifugao: A Study of Environment, Culture, and Society in Northern Luzon. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02529-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jones, Arun W, “A View from the Mountains: Episcopal Missionary Depictions of the Igorot of Northern Luzon, The Philippines, 1903-1916” in Anglican and Episcopal History 71.3 (Sep 2002): 380-410.

- Narita, Tatsushi."How Far is T. S. Eliot from Here?: The Young Poet's Imagined World of Polynesian Matahiva". In How Far is America from Here?, ed. Theo D'haen, Paul Giles, Djelal Kadir and Lois Parkinson Zamora. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2005, pp. 271–282.

- Narita, Tatsushi. T. S. Eliot, the World Fair of St. Louis and 'Autonomy' (Published for Nagoya Comparative Culture Forum). Nagoya: Kougaku Shuppan Press, 2013.

- Rydell, Robert W. All the World's a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916. The University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Cornélis De Witt Willcox (1912). The head hunters of northern Luzon: from Ifugao to Kalinga, a ride through the mountains of northern Luzon : with an appendix on the independence of the Philippines. Volume 31 of Philippine culture series. Franklin Hudson Publishing Co. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Igorot. |