Internet in the Philippines

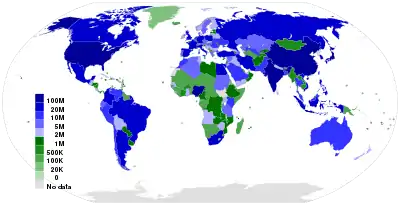

Internet in the Philippines first became available on March 29, 1994, with the Philippine Network Foundation (PHNet) connecting the country and its people to Sprint in the United States via a 64 kbit/s link.[1][2][3] As of January 2020, there are 73,000,000 people using the internet in the country, penetrating 67% of the total population.[4]

History

A year after the connection, the Public Telecommunications Act of the Philippines was made into law. Securing a franchise is now optional for value-added service providers. This law enabled many other organizations to establish connections to the Internet, to create Web sites and have their own Internet services or provide Internet service and access to others.

However the growth of the Internet in the Philippines was hindered by many obstacles including unequal distribution of Internet infrastructure throughout the country, its cost and corruption in the government.[6] But these obstacles did not altogether halt all the developments. More connection types were made available to more Filipinos. Increasing bandwidth and a growing number of Filipino Internet users were proof of the continuing development of the Internet in the country.

The Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012, codified as Republic Act No. 10175, criminalized cybersquatting, cybersex, child pornography, identity theft, illegal access to data and libel.[7] The act has been criticized for its provision on criminalizing libel, which is perceived to be a curtailment in freedom of expression. After several petitions submitted to the Supreme Court of the Philippines questioned the constitutionality of the Act,[8] the Supreme Court issued a temporary restraining order on October 9, 2012, stopping implementation of the Act for 120 days.[9]

A Magna Carta for Philippine Internet Freedom was filed in the Philippine legislature in 2013 to, among others, repeal Republic Act No. 10175.[10] The Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act No 10175 were promulgated on August 12, 2015.[11]

Timeline

The early history of the Internet in the Philippines started with the establishment of Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) by computer hobbyist and enthusiast. They were able to link their BBS’s using a dial-up connection protocol enabling them to participate in discussion forums, send messages and share files.[12][13]

1986: Establishment of first BBS in the Philippines, Star BBS was formed by Efren Tercias and James Chua of Wordtext Systems. Fox BBS was operated by Johnson Sumpio. First-Fil RBBS a public-access BBS went online with an annual subscription fee of P1,000. A precursor to the local online forum, it ran an open-source BBS software on an IBM XT Clone PC with a 1200bit/s modem and was operated by Dan Angeles and Ed Castañeda.

1987: The Philippine FidoNet Exchange, a local network for communication between several BBSes in Metro Manila, was formed.

1990: A committee helmed by Arnie del Rosario of the Ateneo Computer Technology Center was tasked with exploring the possibility of creating an academic network of universities and government institutions by the National Computer Center under Dr. William Torres. Recommendations were made but not implemented.

1991–1993: Emergence of email gateways and services in the Philippines, including some from multinational companies like Intel, Motorola, and Texas Instruments, which used a direct Internet connection, X.25, or UUCP protocol. Local firms ETPI, Philcom, and PLDT (Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company) also operated commercial X.25 networks. Another milestone: Local and international email to FidoNet users was introduced.

June 1993: With the support of the Department of Science and Technology and the Industrial Research Foundation, the Philnet project (now PHNET) was born. The Philnet technical committee, composed of computer buffs working at the DOST [MIS (Joseph Andres), PCASTRD (Merl Opena, Winnefredo Aggabao) and Advanced Science and Technology Institute (Miguel Dimayuga)] and representatives from the Ateneo de Manila University (Richie Lozada and Arnie del Rosario), De La Salle University (Kelsey Hartigan-Go), University of the Philippines Diliman (Rodel Atanacio), University of the Philippines Los Baños (Alfonso Carandang), Xavier University (Bombim Cadiz) and St. Louis University (Ian Generalao); would eventually play a significant role in connecting the Philippines to the global Internet.[14]

July 1993: Phase one of the Philnet project shifted into full gear after receiving funding from the DOST. It proved to be successful, as students from partner universities were able to send emails to the Internet by routing them through Philnet's gateway at the Ateneo de Manila University, which was connected to another gateway at the Victoria University of Technology in Australia via IDD Dial-Up (Hayes Modem).[15]

November 1993: An additional P12.5-million grant for the first year's running cost was awarded by the DOST to buy equipment and lease communication lines needed to kickstart the second phase of Philnet, now led by Dr. Rudy Villarica.

March 29, 1994, 1:15 a.m.: Benjie Tan, who was working for ComNet, a company that supplied Cisco routers to the Philnet project, established the Philippine's first connection to the Internet at a PLDT network center in Makati City. Shortly thereafter, he posted a short message to the Usenet newsgroup soc.culture.filipino to alert Filipinos overseas that a link had been made. His message read: "As of March 29, 1994 at 1:15 am Philippine time, unfortunately 2 days late due to slight technical difficulties, the Philippines was FINALLY connected to the Internet via SprintLink. The Philippine router, a Cisco 7000 router was attached via the services of PLDT and Sprint communications to SprintLink's router at Stockton Ca. The gateway to the world for the Philippines will be via NASA Ames Research Center. For now, a 64K serial link is the information highway to the rest of the Internet world."

March 29, 1994, 10:18 a.m.: "We're in," Dr. John Brule, a Professor Emeritus in Electrical and Computer Engineering at the Syracuse University, announced at The First International E-Mail Conference at the University of San Carlos in Talamban, Cebu, signifying that Philnet's 64 kbit/s connection was live.

Statistics

In 2011, according to AGB Nielsen Philippines, about one of three Filipinos in the Philippines have access to the internet.[17] Among the findings in this report were:

- 43.5% of Filipinos accessed the Internet,[18] five percentage points higher than the Southeast Asian regional average of 38%.

- Internet penetration amongst consumers aged 15 to 19 was close to two-thirds (65%) and nearly half of those in their 20s were online (48%).

- There was still much room for growth for those aged 30+ – less than one quarter of consumers aged in their 30s (24%) access the Internet, 13% of consumers in their 40s, and just 4% of consumers aged 50+.

- 52% of Filipinos had a computer with high speed Internet connection at home.

- Home was the most common Internet access point for those aged 30 years and above close to nine in ten Internet users aged 50 years and above (86%) cite "home" as their main point of access.

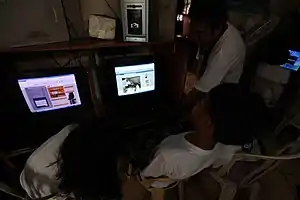

- 74% of 15–19 years identified Internet cafés as their main point of Internet access.

- Close to one quarter of Filipinos Internet users (24%) accessed the Internet on a daily basis via a mobile phone and 56% intend to access the Internet via a mobile phone in the next 12 months.

- Over two thirds of Filipino digital consumers (67%) had visited social networking sites, compared to 40% who used email.

- The Philippines ranked second highest for the number of people who had ever "liked" or followed a brand, company or celebrity on a social networking site (75%).

- 61% of Filipino Internet users said they trusted consumer opinions posted online, higher than any other market in Southeast Asia and seven points above the regional average.

- Online product reviews and discussion forums were one of the most trusted sources of recommendations in purchase decision making, second only to recommendations from family and friends.

- Close to two thirds of digital Filipinos (64%) used social media as a resource in purchase decision making.

Wireless broadband

TD-LTE

As the number of subscribers grew, both PLDT and Globe Telecom rapidly expanded their Time-Division Duplex-Long Term Evolution (TD-LTE) services for Fixed Wireless Broadband. According to PLDT, they spent P2 billion of its P28.8 billion capital expenditure for 2013 to bring TD-LTE technology to customers’ homes. According to industry data, the Philippines’ TD-LTE network was one of the largest deployments in Asia Pacific with over 200 base stations and an allocated bandwidth of 100 megabits per second (Mbps).[19]

In January 2015, both PLDT and Globe Telecom began phasing out WiMax services in favor for TD-LTE.

Bandwidth caps

In October 2015, PLDT introduced so-called "volume boosters" (instead of 30% bandwidth throttling in 2014 and 256kbit/s bandwidth throttling in 2015) when exceeding monthly 30GB to 70GB bandwidth cap for TD-LTE connection plans (Ultera). "In case your usage exceeds your monthly volume allowance, you can still enjoy the internet by purchasing additional volume boosters. Otherwise, connectivity will be halted until your monthly volume is refreshed on your next billing cycle."[20] Globe followed suit with a similar "volume boost" arrangement.[21]

Lock-in period

In 2015, PLDT increased lock-in period for TD-LTE connection plans from 24 to 36 months (3 years) with the pre-termination fee equal to the full balance for the remaining period. After the lock-in period the contract is automatically renewed for another 36 months subject to the same terms and conditions.[22] As of now the Globe lock-in period is still 2 years with no pre-termination fee outside of the lock-in period.[23] The PLDT TD-LTE contract allows PLDT to change the terms and conditions at any time with the only way left for subscribers to opt out of the altered service through paying the full pre-termination fee: "8.3 Modification. SBI reserves the right at its discretion to modify, delete or add to any of the terms and conditions of this Agreement at any time without further notice. It is the Subscriber’s responsibility to regularly check any changes to these Terms and Conditions. The Subscriber’s continued use of the Service after any such changes constitutes acceptance of the new Terms and Conditions."[22] Even as the Consumer Act of the Philippines states "Unfair or Unconscionable Sales Act or Practice ... the following circumstances shall be considered ... that the transaction that the seller or supplier induced the consumer to enter into was excessively one-sided in favor of the seller or supplier",[24] the practice of inducing extremely long term contracts with the ultimate pre-termination penalty has not been legally challenged yet.

IP peering

The Philippines have six Internet Exchange points in the Country. Philippine Open Internet Exchange (PhOPENIX), Philippine Internet Exchange (PhIX), Philippine Common Routing Exchange (PHNET CORE), Globe Internet Exchange (GIX), Bayan Telecommunications Internet and Gaming Exchange and Manila Internet Exchange (Manila IX).

On June 16, 2016, Globe Telecom and PLDT agreed on a bilateral domestic IP peering arrangement.[25]

Internet speed

The Akamai Technologies Q1 2017 State of the Internet report contained information that, though average internet connection speed had increased 20% year-on-year, the Philippines, at 5.5 Mbit/s, once again had the lowest average connection speeds among surveyed Asia Pacific countries/regions. The report noted that Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte had approved a plan with a three to five-year timeline for completion to deploy a national broadband network at an estimated cost of US$1.5 billion to $4.0 billion.[26]

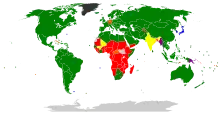

Internet censorship

Access to the Internet in the Philippines stays as unrestricted as the constitutional legislative framework. There are neither overt Internet access government restrictions nor reports that the government monitors e-mail or Internet chat rooms without appropriate legal authority or judicial oversight. Individuals and groups are permitted to engage in the peaceful expression of views via the Internet, including by e-mail.

The constitution and law broadly provide for the right of freedom of thought, expression and press, and the government generally respects these rights in practice. Around 6.5% of the country's population got access to the Internet according to International Telecommunication Union statistics.[27] The constitution and law prohibit arbitrary interference with privacy, family, home, or correspondence, and the authorities generally prohibit those from happening in practice. Internet access is widely available and free to use without any limitations regardless of circumstances.[28]

See also

References

- Miguel A. L. Paraz: Developing a Viable Framework for Commercial Internet Operations in the Asia-Pacific Region: The Philippine Experience. ISOC, INET 1997

- Jim Ayson (29 February 2012). "The Philippine Internet turns 18: Is anyone still counting". GMA News. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Jose Bimbo F. Santos (20 March 2014). "PHNET – Philippine Internet connection turns 20 years old this month". InterAksyon.com. Archived from the original on 2014-03-28. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- "Digital 2020: The Philippines". DataReportal – Global Digital Insights. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- "Percentage of Individuals using the Internet 2000–2012", International Telecommunications Union (Geneva), June 2013, retrieved 22 June 2013

- Philippines – Public Access Landscape Study Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Research Team Emmanuel Lallana, University of Washington Center for Information & Society (CIS), 2009.

- Republic Act No. 10175, An Act Defining Cybercrime, Providing for the Prevention, Investigation, Suppression and the Imposition of Penalties therefor and for Other Purposes. Approved by President of the Philippines BENIGNO S. AQUINO III on September 12, 2012

- Canlas, Jonas (27 September 2012). "Suits pile up assailing anti-cybercrime law". The Manila Times. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- Torres, Tetch (9 October 2012). "SC issues TRO vs cyber law". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Philippine Daily Inquirer, Inc. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- "The Wisdom of Crowds: Crowdsourcing Net Freedom", Jonathan de Santos, Yahoo! News Philippines, 21 January 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act No 1017.

- "RP marks 7th year on the Internet : Digital Life by Chin Wong". www.chinwong.com.

- "#20PHnet: A timeline of Philippine Internet".

- "Villarica: The day the Philippines ‘discovered’ the world", Dr. Rodolfo M. Villarica, Newsbytes.ph, 05 April 2014.

- "About PHNET". www.ph.net.

- Top 5 browsers in Philippines on February 2013 Statcounter Global Stats

- One in three consumers in the Philippines are now accessing the Internet. social networking playing an increasing role in consumer purchasing decisions AGB Nielsen Philippines Manila, 12 July 2011. The report is a pre-release of data from Nielsen's inaugural Southeast Asia Digital Consumer Report available September 30, 2011.

- "Internet Users by Country (2016)". internetlivestats.com.

- "PLDT, Globe in race to modernize networks – The Manila Times Online". The Manila Times Online.

- "PLDT HOME Ultera support library, FAQ".

- "Globe – FAQ – Volume Boost".

- "Terms and Conditions".

- "Tattoo Free Installation Promo>FAQs". Archived from the original on 2016-06-26. Retrieved 2016-06-29.

- "Republic Act No. 7925: the Consumer Act of the Philippines".

- "Three ways you will feel the effects of Globe-PLDT IP Peering". The Philippine Star. June 20, 2016.

- akamai's [state of the internet] Q1 2017 report (PDF) (Report). Akamai Technologies. pp. 27, 28.

- "2010 Human Rights Report: Philippines", Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State. 2011-04-08

- "2010 Human Rights Report: Philippines", Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State. 2011-04-08

External links

Media related to Internet in the Philippines at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Internet in the Philippines at Wikimedia Commons