Invasion of Algiers in 1830

The Invasion of Algiers in 1830 was a large-scale military operation by which the Kingdom of France, ruled by Charles X, invaded and conquered the Regency of Algiers. Algiers had been nominally part of the Ottoman Empire since the Capture of Algiers in 1529 by Hayreddin Barbarossa.

| Invasion of Algiers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Conquest of Algeria | |||||||

Attaque d'Alger par la mer 29 Juin 1830, Théodore Gudin | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

French army French navy | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

64,612 103 warships 464 transport ships | 10,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,575 killed and wounded[1] | 1,500 killed and wounded | ||||||

A diplomatic incident in 1827, the so-called Fan Affair (Fly Whisk Incident), served as a pretext to initiate a blockade against the port of Algiers. After three years of standstill and a more severe incident in which a French ship carrying an ambassador to the dey with a proposal for negotiations was bombarded, the French determined that more forceful action was required. Charles X was also in need of diverting attention from turbulent French domestic affairs that culminated with his deposition during the later stages of the invasion in the July Revolution.

The invasion of Algiers began on 5 July 1830 with a naval bombardment by a fleet under Admiral Duperré and a landing by troops under Louis Auguste Victor de Ghaisne, comte de Bourmont. The French quickly defeated the troops of Hussein Dey, the Ottoman ruler, but native resistance was widespread. This resulted in a protracted military campaign, lasting more than 45 years, to root out popular opposition to the colonisation. The so-called "pacification" was marked by resistance of figures such as Ahmed Bey, Abd El-Kader and Lalla Fatma N'Soumer.

The invasion marked the end of several centuries of Ottoman rule in Algeria and the beginning of French Algeria. In 1848, the territories conquered around Algiers were organised into three départements, defining the territories of modern Algeria.

Background

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Regency of Algiers had greatly benefited from trade in the Mediterranean, and of the massive imports of food by France, largely bought on credit. The Dey of Algiers attempted to remedy his steadily decreasing revenues by increasing taxes, which was resisted by the local peasantry, increasing instability in the country and leading to increased piracy against merchant shipping from Europe and the young United States of America. This, in turn, led to the First Barbary War and the Second Barbary War, which culminated in August 1816 when Edward Pellew executed a naval bombardment of Algiers in response to Algerian massacres of recently freed European slaves.

The widespread unpopularity of the Bourbon Restoration among the French populace at large also made France unstable. In an attempt to distract his people from domestic affairs, King Charles X decided to engage in a colonial expedition.

In 1827, Hussein Dey, Algeria's Ottoman ruler, demanded that the French pay a 28-year-old debt contracted in 1799 by purchasing supplies to feed the soldiers of the Napoleonic Campaign in Egypt. The French consul Pierre Deval refused to give answers satisfactory to the dey, and in an outburst of anger, Hussein Dey touched the consul with his fly-whisk. Charles X used this as an excuse to initiate a blockade against the port of Algiers. The blockade lasted for three years, and was primarily to the detriment of French merchants who were unable to do business with Algiers, while Barbary pirates were still able to evade the blockade. When France in 1829 sent an ambassador to the dey with a proposal for negotiations, he responded with cannon fire directed toward one of the blockading ships. The French then determined that more forceful action was required.[2]

King Charles X decided to organise a punitive expedition on the coasts of Algiers to punish the "impudence" of the dey, as well as to root out Barbary corsairs who used Algiers as a safe haven. The naval part of the operation was given to Admiral Duperré, who advised against it, finding it too dangerous. He was nevertheless given command of the fleet. The land part was under the orders of Louis Auguste Victor de Ghaisne, comte de Bourmont.

On 16 May, a fleet comprising 103 warships and 464 transports departed Toulon, carrying a 37,612-man strong army. The ground was well-known, thanks to observations made during the First Empire, and the Presque-isle of Sidi Ferruch was chosen as a landing spot, 25 kilometres (16 mi) west of Algiers. The vanguard of the fleet arrived off Algiers on 31 May, but it took until 14 June for the entire fleet to arrive.

Order of battle

French Navy

- Hercule (74), flagship. Admiral Duperré

- Marengo (74)

- Trident (74)

- Duquesne (80), captain Bazoche

- Algésiras (80)

- Conquérant (80)

- Breslaw (80)

- Couronne (74)

- Ville de Marseille (74), en flûte

- Pallas (60),

- Melpomène (60),

- Aréthuse (46), en flûte

- Pauline (44)

- Thétis (44)

- Proserpine (44)

- Sphinx

- Nageur

Invasion

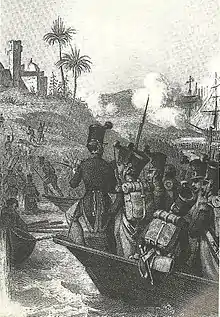

French troops landed at Sidi Fredj[3] on 14 June 1830 against minimal opposition. Within a few days, however, troops of Algerian caids started to rise against the invaders. On 18 June, Hussein Dey assembled a 10,000-man army, comprising 1,000 Janissaries, 5,000 Moors and 3,000 Arabs and Berbers from Oran, Titteri and Medea. Bourmont merely kept the counter-attacks at bay until 28 June, when siege weapons were landed, making it possible to attack Algiers itself.

Sultan-Khalessi, the main fort defending the city, was attacked on 29 June and fell on 4 July. The Bey then started negotiations, leading to his capitulation the next day. At the same time, in France, the July Revolution led to the deposition of Charles X. French troops entered the city on 5 July, and evacuated the Casbah on 7 July. The French had 415 killed.

The Dey was exiled to Naples, and some of the Janissaries to the Ottoman Empire. Bourmont immediately instituted a municipal council and a governmental commission to administer the city.

Before the new status of Algiers could be settled, Bourmont struck at Blida and occupied Bône and Oran in early August. On 11 August, news of the July Revolution reached Algiers, and Bourmont was required to pledge allegiance to Charles' successor Louis-Philippe, which he refused to do. He was relieved of command and replaced by general Bertrand Clauzel on 2 September. Negotiations were started with the beys of Titteri, Oran and Constantine to impose a French protectorate, spreading French influence over the entire former Regency.

Effects

With the French invasion of Algiers, a number of Algerians migrated west to Tetuan. They introduced baklava, coffee, and the warqa pastry now used in pastilla.[4][5]

References

- "Conquête d'Alger ou pièces sur la conquête d'Alger et sur l'Algérie". 1 January 1831 – via Google Books.

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-521-33767-0.

- "Sidi Fredj". www.sea-seek.com. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- Gaul, Anny (27 November 2019). "Bastila and the Archives of Unwritten Things". Maydan. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

I was especially interested in Tetouani baqlawa, a pastry typically associated with the eastern Mediterranean, not the west. The baqlawa we sampled was shaped in a spiral, unlike the diamond-shaped version I was more familiar with from Levantine food. But its texture and flavors––thin buttered layers of crisp papery pastry that crunch around sweet fillings with honeyed nuts––were unmistakable. Instead of the pistachios common in eastern baqlawa, El Mofaddal’s version was topped with toasted slivered almonds. Was baqlawa the vehicle that had introduced phyllo dough to Morocco?

There is a strong argument for the Turkic origin of phyllo pastry, and the technique of shaping buttered layers of it around sweet and nut-based fillings was likely developed in the imperial kitchens of Istanbul.[4] So my next step was to find a likely trajectory that phyllo dough might have taken from Ottoman lands to the kitchens of northern Morocco.

It so happened that one of Dr. Bejjit’s colleagues, historian Idriss Bouhlila, had recently published a book about the migration of Algerians to Tetouan in the nineteenth/thirteenth century. His work explains how waves of Algerians migrated to Tetouan fleeing the violence of the 1830 French invasion. It includes a chapter that traces the influences of Ottoman Algerians on the city’s cultural and social life. Turkish language and culture infused northern Morocco with new words, sartorial items, and consumption habits––including the custom of drinking coffee and a number of foods, especially sweets like baqlawa. While Bouhlila acknowledges that most Tetouanis consider bastila to be Andalusi, he suggests that the word itself is of Turkish origin and arrived with the Algerians."

...

"Bouhlila’s study corroborated the theory that the paper-thin ouarka used to make bastila, as well as the name of the dish itself, were introduced to Morocco by way of Tetouani cuisine sometime after 1830. - Idriss Bouhlila. الجزائريون في تطوان خلال القرن 13هـ/19م. pp. 128–129.

.png.webp)