Invasion of Martinique (1809)

The Invasion of Martinique of 1809 was a successful British amphibious operation against the French West Indian island of Martinique that took place between 30 January and 24 February 1809 during the West Indies Campaign 1804–1810 of the Napoleonic Wars. Martinique, like nearby Guadeloupe, was a major threat to British trade in the Caribbean, providing a sheltered base from which privateers and French Navy warships could raid British shipping and disrupt the trade routes that maintained the British economy. The islands also provided a focus for larger scale French operations in the region and in the autumn of 1808, following the Spanish alliance with Britain, the Admiralty decided to order a British squadron to neutralise the threat, beginning with Martinique.

| Invasion of Martinique | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

The Taking of the French Island of Martinique in the French West Indies on Feb 24th 1809, George Thompson | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

10,000 6 ships of the line 8 frigates 9 brigs |

4,900 3 brigs | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 97 killed, 365 wounded, 18 missing | 900 killed, wounded and missing | ||||||

The British mustered an overwhelming force under Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane and Lieutenant-General George Beckwith, who collected 29 ships and 10,000 men – almost four times the number of French regular forces garrisoning Martinique. Landing in force on both the southern and northern coasts of the island, British troops pushed inland, defeating French regulars in the central highlands and routing local militia units in the south of the island. By 9 February, the entire island was in British hands except Fort Desaix, a powerful position intended to protect the capital Fort-de-France, which had been bypassed during the British advance. In a siege lasting 15 days the Fort was constantly bombarded, the French suffering 200 casualties before finally surrendering.

The capture of the island was a significant blow to French power in the region, eliminating an important naval base and denying safe harbours to French shipping in the region. The consequences of losing Martinique were so severe, that the French Navy sent a battle squadron to reinforce the garrison during the invasion. Arriving much too late to affect the outcome, these reinforcements were intercepted off the islands and scattered during the Action of 14–17 April 1809: half the force failed to return to France. With Martinique defeated, British attention in the region turned against Guadeloupe, which was captured the following year.

Background

During the Napoleonic Wars, the British Royal Navy was charged with limiting the passage and operations of the French Navy, French merchant ships and French privateers. To achieve this objective, the Royal Navy imposed a system of blockades on French ports, especially the major naval bases at Toulon and Brest. This stranglehold on French movement off their own coastline seriously affected the French colonies, including those in the West Indies, as their produce could not reach France and supplies and reinforcements could not reach them without the risk of British interception and seizure.[1] These islands provided excellent bases for French ships to raid the British trade routes through the Caribbean Sea: in previous conflicts, the British had countered the threat posed by French West Indian colonies by seizing them through force, such as Martinique, which had been previously captured by armed invasion in 1762 and 1794.[2] An attempt in 1780 was defeated by a French battle squadron at the Battle of Martinique. By 1808 there were no French squadrons at sea: any that left port were eliminated or driven back in a series of battles, culminating at the disastrous defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. The fleet that was destroyed at Trafalgar had visited Martinique the year before and was the last full-scale French fleet to visit the Caribbean for the rest of the war.[3]

With the bulk of the French Navy confined to port, the British were able to strike directly at French colonies, although their reach was limited by the significant resources required in blockading the French coast and so the size and quality of operations varied widely. In 1804, Haiti fell to a nationalist uprising supported by the Royal Navy, and in 1806 British forces secured most of the northern coast of South America from its Dutch owners. In 1807 the Danish West Indies were invaded and in 1808 Spain changed sides and allied with Britain, while Cayenne fell to an improvised force under Captain James Lucas Yeo in January 1809.[4] The damage done to the Martinique economy during this period was severe, as British frigates raided coastal towns and shipping, and merchant vessels were prevented from trading Martinique's produce with France or allied islands. Disaffection grew on the island, especially among the recently emancipated black majority, and during the summer of 1808 the island's governor, Vice-amiral Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse, sent urgent messages back to France requesting supplies and reinforcements.[5] Some of these messages were intercepted by British ships and the low morale on Martinique was brought to the attention of the Admiralty, who ordered their commander on the West Indian Station, Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, to raise an expeditionary force from the ships and garrisons available to him and invade the island.[6]

During the winter of 1808–1809, Cochrane gathered his forces off Carlisle Bay, Barbados, accumulating 29 ships and 10,000 soldiers under the command of Lieutenant-General George Beckwith.[7] Landings were planned on the island's southern and northern coasts, with the forces ordered to converge on the capital Fort-de-France. The soldiers would be supported and supplied by the Royal Navy force, which would shadow their advance offshore. Beckwith's army was more than twice the size of the French garrison, half of which was composed of an untrained and irregular black militia which could not be relied on in combat.[6] News of the poor state of Martinique's defences also reached France during the autumn of 1808. Attempts were made to despatch reinforcements and urgently needed food supplies, but on 30 October 1808 Circe captured the 16-gun French Curieux class brig Palinure. The British then captured the frigate Thétis in the Bay of Biscay at the Action of 10 November 1808. Another relief attempt was destroyed in December off the Leeward Islands and HMS Aimable captured the corvette Iris, carrying flour to Martinique, off the Dutch coast on 2 January 1809.[8] Only the frigate Amphitrite, whose stores and reinforcements were insignificant compared to the forces under Cochrane and Beckwith, managed to reach Martinique.[9]

Invasion

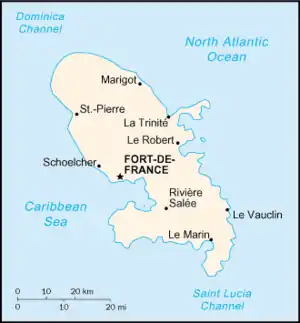

Cochrane's fleet sailed from Carlisle Bay on 28 January, arriving off Martinique early on 30 January. The force was then divided, one squadron anchoring off Sainte-Luce on the southern coast and another off Le Robert on the northern.[10] The invasion began the same morning, 3,000 soldiers going ashore at Sainte-Luce under the command of Major-General Frederick Maitland, supervised by Captain William Charles Fahie, while 6,500 landed at Le Robert under Major-General Sir George Prevost, supervised by Captain Philip Beaver. Beckwith remained on Cochrane's flagship HMS Neptune, to direct the campaign from offshore.[11] A third force, under a Major Henderson and consisting entirely of 600 soldiers from the Royal York Rangers, landed at Cape Salomon near Les Anses-d'Arlet on the southwestern peninsula to secure the entrance to Fort-de-France Bay.[12]

During the first day of the invasion, the two main forces made rapid progress inland, the militia troops sent against them retreating and deserting without offering resistance. Serious opposition to the British advance did not begin until 1 February, when French defenders on the heights of Desfourneaux and Surirey were attacked by Prevost's troops, under the direct command of Brigadier-General Daniel Hoghton. Fighting was fierce throughout the next two days, as the outnumbered French used the fortified high ground to hold back a series of frontal assaults. The British lost 84 killed and 334 wounded to French losses of over 700 casualties, and by 3 February the French had been forced back, withdrawing to Fort Desaix near the capital.[13] Progress was also made at Cape Salomon, where the appearance of British troops panicked the French defenders into burning the naval brig Carnation and retreating to the small island, Ilot aux Ramiers, offshore. Henderson's men, assisted by a naval brigade under Captain George Cockburn, set up batteries on the coast and by 4 February had bombarded the island into surrender, opening the principal harbour of Martinique to naval attack.[11]

A small naval squadron, consisting of HMS Aeolus, HMS Cleopatra and the brig HMS Recruit, advanced into Fort-de-France Bay on 5 February. This advance spread panic among the French militia defending the bay and Amphitrite and the other shipping anchored there were set on fire and destroyed, while the forts in the southern part of the island were abandoned.[12] On 8 February, Maitland's force, which had not yet fired a shot, arrived on the western side of Fort Desaix and laid siege to it. Minor detachments spread across the remainder of the island: Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Barnes captured Saint-Pierre and another force occupied Fort-de-France and seized the corvette Diligente in the harbour. By 10 February, when Prevost's force linked up with Maitland's, Fort Desaix was the only remaining point of resistance.[11]

For nine days, the British soldiers and sailors of the expeditionary force constructed gun batteries and trenches around the fort, bringing ashore large quantities of supplies and equipment in readiness for a lengthy siege. At 16:30 on 19 February the preparations were complete and the bombardment began, 14 heavy cannon and 28 mortars beginning a continuous attack on the fort which lasted for the next four days. French casualties in the overcrowded fort were severe, with 200 men killed or wounded. British casualties were minimal, with five killed and 11 wounded, principally in an explosion in an ammunition tent manned by sailors from HMS Amaranthe.[14] At 12:00 on 23 February, Villaret de Joyeuse's trumpeter was sent to the British camp with a message proposing surrender terms. These were unacceptable to Beckwith and the bombardment resumed at 22:00, continuing until 09:00 the following morning when three white flags were raised over the fort and the French admiral surrendered unconditionally. The bombardment had cracked the roof of the fort's magazine, and there were fears that further shelling might have ignited the gunpowder and destroyed the building completely.[14]

Aftermath

_Monument%252C_St._George's_Church%252C_Halifax%252C_Nova_Scotia.jpg.webp)

With the surrender of Fort Desaix, British forces solidified their occupation of the island of Martinique. The remaining shipping and military supplies were seized and the regular soldiers of the garrison taken as prisoners of war. The militia were disbanded and Martinique became a British colony, remaining under British command until the restoration of the French monarchy in 1814, when it was returned to French control.[15] British losses in the campaign were heavy, with 97 killed, 365 wounded and 18 missing. French total losses are uncertain but the garrison suffered at least 900 casualties, principally in the fighting in the central highlands on 1 and 2 February and during the siege of Fort Desaix.[14] Upon his return to France, Villaret's conduct was condemned by an inquiry council; he requested in vain a Court-martial to clear his name, and lived in disgrace for two years.[16]

In Britain, both Houses of Parliament voted their thanks to Cochrane and Beckwith, who immediately began planning the invasion of Guadeloupe, executed in January 1810. Financial and professional rewards were provided for the junior officers and enlisted men and in 1816 the battle honour Martinique was awarded to the ships and regiments involved, with the date 1809 added in 1909 to distinguish the campaign from the earlier operations of 1762 and 1794.[17] Four decades later the operation was among the actions recognised by a clasp attached to the Naval General Service Medal and the Military General Service Medal, awarded upon application to all British participants still living in 1847.[18] In France, the defeat was the subject of a court martial in December 1809, at which Villaret de Joyeuse and a number of his subordinates were stripped of their commissions, honours, and ranks for inadequately preparing for invasion, in particular for failing properly to strengthen and disperse the magazine at Fort Desaix.[11]

There was a subsequent French effort to reach Martinique, launched in February 1809 before news of the British invasion had reached Europe. Three ships of the line and two disarmed frigates were sent with soldiers and supplies towards the island, but learned of Villaret de Joyeuse's surrender in late March and instead took shelter in the Îles des Saintes, blockaded by Cochrane's squadron.[19] On 14 April, Cochrane seized the Saintes and the French fled, the three ships of the line drawing away Cochrane's forces so that the frigates could slip away and reach Guadeloupe. During the ensuing Action of 14–17 April 1809, the French flagship Hautpoult was chased down and captured, but two ships of the line escaped and the frigates reached Guadeloupe, although neither would ever return to France.[20]

British order of battle

| Admiral Cochrane's squadron | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ship | Rate | Guns | Navy | Commander | Notes |

| HMS Neptune | Second rate | 98 | Rear-Admiral Hon. Sir Alexander Cochrane Captain Charles Dilkes |

||

| HMS Pompee | Third rate | 74 | Commodore George Cockburn | ||

| HMS York | Third rate | 74 | Captain Robert Barton | ||

| HMS Belleisle | Third rate | 74 | Captain William Charles Fahie | ||

| HMS Captain | Third rate | 74 | Captain James Athol Wood | ||

| HMS Intrepid | Third rate | 64 | Captain Christopher Nesham | ||

| HMS Ulysses | Fifth rate | 44 | Captain Edward Woollcombe | ||

| HMS Acasta | Fifth rate | 40 | Captain Philip Beaver | ||

| HMS Penelope | Fifth rate | 36 | Captain John Dick | ||

| HMS Ethalion | Fifth rate | 38 | Captain Thomas John Cochrane | ||

| HMS Aeolus | Fifth rate | 32 | Captain Lord William FitzRoy | ||

| HMS Circe | Fifth rate | 32 | Captain Hugh Pigot | ||

| HMS Cleopatra | Fifth rate | 38 | Captain Samuel John Broke Pechell | ||

| HMS Eurydice | Sixth rate | 24 | Captain James Bradshaw | ||

| HMS Cherub | Brig | 18 | Commander Thomas Tudor Tucker | ||

| HMS Goree | Brig | 18 | Commander Joseph Spear | ||

| HMS Starr | Brig | 18 | Commander Francis Augustus Collier | ||

| HMS Stork | Brig | 18 | Commander George Le Geyt | ||

| HMS Amaranthe | Brig | 18 | Commander Edward Pelham Brenton | ||

| HMS Forester | Brig | 18 | Commander John Richards | ||

| HMS Frolic | Brig | 18 | Commander Thomas Whinyates | ||

| HMS Recruit | Brig | 18 | Commander Charles John Napier | ||

| HMS Wolverine | Brig | 18 | Commander John Simpson | ||

| In addition, the invasion fleet included 21 smaller warships and a number of transports. The British Army troops attached to the force included soldiers from the 7th Foot, 8th Foot, 23rd Foot, 13th Foot, 90th Foot, 15th Foot, 60th Rifles, 63rd Foot, 25th Foot, 1st West India Regiment and the Royal York Rangers. The expeditionary force was commanded by Lieutenant-General George Beckwith who remained offshore. Direct command of the land campaign was given to Major-General Frederick Maitland and Major-General Sir George Prevost, who delegated tactical command to Brigadier-General Daniel Hoghton. | |||||

| Sources: James Vol. 5, p. 206, Clowes, p. 283, Gardiner, p. 77, Rodger, p. 36 | |||||

Notes

- Gardiner, p. 17

- Rodger, p. 74

- Gardiner, p. 59

- Gardiner, p. 76–77

- James, p. 206

- Clowes, p. 283

- Woodman, p. 242

- Clowes, p. 430

- Gardiner, p. 75

- James, p. 207

- Clowes, p. 284

- Gardiner, p. 77

- James, p. 208

- James, p. 209

- Chandler, p. 328

- Hennequin, p.220

- Rodger, p. 36

- "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 242.

- Gardiner, p. 78

- Woodman, p. 243

References

- Chandler, David (1999) [1993]. Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. Wordsworth Military Library. ISBN 1-84022-203-4.

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume V. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-014-0.

- Gardiner (ed.), Robert (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Hennequin, Joseph François Gabriel (1835). Biographie maritime ou notices historiques sur la vie et les campagnes des marins célèbres français et étrangers (in French). 2. Paris: Regnault éditeur.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 5, 1808–1811. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-909-3.

- Rodger, Alexander (2003). Battle Honours of the British Empire and Commonwealth Land Forces. Marlborough: The Crowood Press. ISBN 1-86126-637-5.

- Woodman, Richard (2001). The Sea Warriors. Constable Publishers. ISBN 1-84119-183-3.