Japanese craft

Craft (工芸, kōgei, lit. engineered art) in Japan has a long tradition and history. Included are handicraft by an individual or a group, and a craft is work produced by independent studio artists, working with traditional craft materials and/or processes.

History

Japanese craft dates back since humans settled on its islands. Handicrafting has its roots in the rural crafts – the material-goods necessities – of ancient times. Handicrafters used natural, indigenous materials, which continues to be emphasised today for the most part. Traditionally, objects were created to be used and not just to be displayed and thus, the border between craft and art was not always very clear. Crafts were needed by all strata of society and became increasingly sophisticated in their design and execution. Craft had close ties to folk art, but developed into fine art as well as the concept of wabi-sabi aesthetics. Craftsmen and women therefore became artisans with increasing sophistication. However wares were not just produced for domestic consumption, but at some point items such as ceramics made by studio craft were produced for export and became an important pillar of the economy.

Family affiliations or bloodlines are of special importance to the aristocracy and the transmission of religious beliefs in various Buddhist schools. In Buddhism, the use of the term "bloodlines" likely relates to a liquid metaphor used in the sutras: the decantation of teachings from one "dharma vessel" to another, describing the full and correct transference of doctrine from master to disciple. Similarly, in the art world, the process of passing down knowledge and experience formed the basis of familial lineages. For ceramic, metal, lacquer, and bamboo craftsmen, this acquisition of knowledge usually involved a lengthy apprenticeship with the master of the workshop, often the father of the young disciple, from one generation to the next. In this system called Dentō (伝 統), traditions were passed down within a teacher-student relationship (shitei 師弟). It encompassed strict rules that had to be observed in order to enable learning and teaching of a way (dō 道). The wisdom could be taught either orally (Denshō 伝承), or in writing (Densho 伝書). Living in the master's household and participating in household duties, apprentices carefully observed the master, senior students, and workshop before beginning any actual training. Even in the later stages of an apprenticeship it was common for a disciple to learn only through conscientious observation. Apprenticeship required hard work from the pupil almost every day in exchange for little or no pay. It was quite common that the mastery in certain crafts were passed down within the family from one generation to the next, establishing veritable dynasties. In that case the established master's name was assumed instead of the personal one. Should there be an absence of a male heir, a relative or a student could be adopted in order to continue the line and assume the prestigious name.

With the end of the Edo period and the advent of the modern Meiji era, industrial production was introduced; western objects and styles were copied and started replacing the old. On the fine art level, patrons such as feudal daimyō lords were unable to support local artisans as much as they had done in the past. Although handmade Japanese craft was once the dominant source of objects used in daily life, modern era industrial production as well as importation from abroad sidelined it in the economy. Traditional craft began to wane, and disappeared in many areas, as tastes and production methods changed. Forms such as swordmaking became obsolete. Japanese scholar Okakura Kakuzō wrote against the fashionable primacy of western art and founded the periodical Kokka (國華, lit. Flower of the Nation) to draw attention to the issue. Specific crafts that had been practiced for centuries were increasingly under threat, while others that were more recent developments introduced from the west, such as glassmaking, saw a rise.

Although these objects were designated as National Treasures – placing them under the protection of the imperial government – it took some time for their intangible cultural value to be fully recognized. In order to further protect traditional craft and arts, the government, in 1890, instituted the guild of Imperial Household Artists (帝室技芸員, Teishitsu Gigei-in), who were specially appointed to create works of art for the Tokyo Imperial Palace and other imperial residences. These artists were considered most famous and prestigious and worked in the areas such as painting, ceramics, and lacquerware. Although this system of patronage offered them some kind of protection, craftsmen and women on the folk art level were left exposed. One reaction to this development was the mingei (民芸, "folk arts" or "arts of the people") – the folk art movement that developed in the late 1920s and 1930s, whose founding father was Yanagi Sōetsu (1889–1961). The philosophical pillar of mingei was "hand-crafted art of ordinary people" (民衆的な工芸 (minshū-teki-na kōgei)). Yanagi Sōetsu discovered beauty in everyday ordinary and utilitarian objects created by nameless and unknown craftspersons.

The Second World War left the country devastated and as a result, craft suffered. The government introduced a new program known as Living National Treasure to recognise and protect craftspeople (individually and as groups) on the fine and folk art level. Inclusion in the list came with financial support for the training of new generations of artisans so that the art forms could continue. In 1950, the national government instituted the intangible cultural properties categorization, which is given to cultural property considered of high historical or artistic value in terms of the craft technique. The term refers exclusively to the human skill possessed by individuals or groups, which are indispensable in producing cultural property. It also took further steps: in 2009, for example, the government inscribed yūki-tsumugi into the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists. Prefectural governments, as well as those on the municipal level, also have their own system of recognising and protecting local craft. Although the government has taken these steps, private sector artisans continue to face challenges trying to stay true to tradition whilst at the same time interpreting old forms and creating new ideas in order to survive and remain relevant to customers. They also face the dilemma of an ageing society wherein knowledge is not passed down to enough pupils of the younger generation, which means dentō teacher-pupil relationships within families break down if a successor is not found.[1] As societal rules changed and became more relaxed, the traditional patriarchal system has been forced to undergo changes as well. In the past, males were predominantly the holders of "master" titles in the most prestigious crafts. Ceramist Tokuda Yasokichi IV was the first female to succeed her father as a master, since he did not have any sons and was unwilling to adopt a male heir. Despite modernisation and westernisation, a number of art forms still exist, partly due to their close connection to certain traditions: examples include the Japanese tea ceremony, ikebana, and to a certain degree, martial arts (in the case of swordmaking).

The Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition (日本伝統工芸展) takes place every year with the aim of reaching out to the public.[2] In 2015, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York exhibited a number of modern kōgei artists in an effort to introduce Japanese craft to an international audience.[3][4]

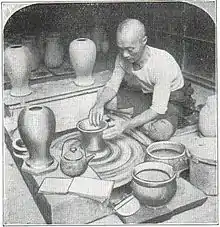

Ceramics

Japanese pottery and porcelain, one of the country's oldest art forms, dates back to the Neolithic period. Kilns have produced earthenware, pottery, stoneware, glazed pottery, glazed stoneware, porcelain, and blue-and-white ware. Japan has an exceptionally long and successful history of ceramic production. Earthenware was created as early as the Jōmon period (10,000–300 BCE), giving Japan one of the oldest ceramic traditions in the world. Japan is further distinguished by the unusual esteem that ceramics holds within its artistic tradition, owing to the enduring popularity of the tea ceremony.

Some of the recognised techniques of Japanese ceramic craft are:[5]

- Iro-e (色絵), colour painting

- Neriage (練上げ), using different colours of clay together

- Sansai (三彩), three colours of brown, green, and a creamy off-white

- Saiyū (彩釉), glaze technique with dripping effect

- Seihakuji (青白磁), a form of blue-white hakuji porcelain

- Sometsuke (染付), blue and white pottery

- Tetsu-e (鉄絵) (also known as Tetsugusuri), iron glazing

- Yūri-kinsai (釉裏金彩), metal-leaf application

- Zōgan (象嵌), damascening and champlevé

There are many different types of Japanese ware. Those more identified as being close to the craft movement include:[5]

- Bizen ware (備前焼), from Imbe in Bizen province

- Hagi ware (萩焼), from Hagi, Yamaguchi prefecture

- Hasami ware (波佐見焼), from Hasami, Nagasaki prefecture

- Kakiemon (柿右衛門), porcelain developed by Sakaida Kakiemon in Arita, Saga prefecture

- Karatsu ware (唐津焼), from Karatsu, Saga prefecture

- Kutani ware (九谷焼), from Kutani, Ishikawa prefecture

- Mashiko ware (益子焼), from Mashiko, Tochigi prefecture

- Mumyōi ware (無名異焼), from Sado, Niigata prefecture

- Onta ware (小鹿田焼), from Onta, Ōita prefecture

- Setoguro (瀬戸黒), from Seto, Aichi prefecture

- Shigaraki ware (信楽焼), from Shigaraki, Shiga prefecture

- Shino ware (志野焼), from Mino province

- Tokoname ware (常滑焼), from Tokoname, Aichi prefecture

- Tsuboya ware (壺屋焼), from Ryūkyū Islands

Textiles

Textile crafts include silk, hemp, and cotton woven (after spinning and dyeing) into various forms—from timeless folk designs to complex court patterns. Village crafts that evolved from ancient folk traditions also continued in the form of weaving and indigo dyeing—by the Ainu people of Hokkaidō (whose distinctive designs have prehistoric prototypes) and by other remote farming families in northern Japan.

Textiles were used primarily for Japanese clothing and include furisode, jūnihitoe, kimono, sokutai, yukata, obi, and many other items. Headgear could include kanzashi while footwear such as geta also needed textiles.

The different techniques for dyeing designs onto fabric are:[6]

The weaving technique for dyed threads to make fabric are:[6]

- Kasuri (絣織)

- Pongee (紬織)

- Echigo jofu (越後上布)

- Saga-nishiki brocade (佐賀錦)

- Kumihimo braid-making (組紐)

- embroidery (刺繍)

Amongst the more well-known regional types are:[6]

- Nishijin-ori (西陣織), silkwork from Nishijin, Kyoto city

- Yūki-tsumugi (結城紬), silkwork from Yūki, Ibaraki prefecture

- Kumejima-tsumugi (久米島紬), silkwork from Kumejima, Okinawa

- Kagayūzen (加賀友禅), dyeing from Kaga, Ishikawa prefecture

- Kyōyūzen (京友禅), dyeing from Kyoto

Lacquerware

Japanese lacquerware can be traced to prehistoric finds. It is most often made from wooden objects, which receive multiple layers of refined lac juices, each of which must dry before the next is applied. These layers make a tough skin impervious to water damage and resistant to breakage, providing lightweight, easy-to-clean utensils of every sort. The decoration on such lacquers, whether carved through different colored layers or in surface designs, applied with gold or inlaid with precious substances, has been a prized art form since the Nara period (A.D. 710-94).

Items produced are for daily necessities like bowls and trays, but also as tea ceremony utensils such as chaki tea caddies and kōgō incense containers. Items included in the past were also netsuke and inrō.

Japanese lacquerware is closely entwined with wood and bamboo work; the base material is usually wood, but bamboo (藍胎 rantai) or linen (乾漆 kanshitsu) can also be used.[7]

The different techniques to coat and paint are:[7]

- Urushi-e (漆絵), which is the oldest and most basic decorative technique

- Maki-e (蒔絵)

- Raden (螺鈿)

- Chinkin (沈金)

- Kinma (蒟醤)

- Choshitsu (彫漆)

- Hiramon (平文)

- Rankaku (卵殻)

- Kamakura-bori (鎌倉彫)

Amongst the more well-known types are:[7]

- Wajima-nuri (輪島塗), lacquerware from Wajima, Ishikawa prefecture

- Tsugaru-nuri (津軽塗), lacquerware from Tsugaru region around Hirosaki, Aomori prefecture

Wood and bamboo

.jpg.webp)

Wood and bamboo have had a place in Japanese architecture and art since the beginning due to an abundance of this plant material on the Japanese island, and its relative ease of use. Japanese carpentry has a long tradition. Secular and religious buildings were made out of this material as well as items used in the household—normally dishes and boxes.

Other items of woodwork are yosegi and the making of furniture such as tansu. The Japanese tea ceremony is closely entwined with bamboowork for spoons, and woodwork and lacquerware for natsume.

Types of woodwork include:[8]

- Sashimono (指物)

- Kurimono (刳物)

- Hikimono (挽物)

- Magemono (曲物)

Japanese bamboowork implements are produced for tea ceremonies, ikebana flower arrangement and interior goods. The types of bamboowork are:[8]

- Amimono (編物)

- Kumimono (組物)

The art of basket weaving such as kagome (籠目) is well known; its name is composed from the words kago (basket) and me (eyes), referring to the pattern of holes in a woven basket. It is a woven arrangement of laths composed of interlaced triangles such that each point where two laths cross has four neighboring points, forming the pattern of trihexagonal tiling. The weaving process gives the kagome a chiral wallpaper group symmetry, p6 (632).

Other materials such as reeds can also be included. Neko Chigura is a traditional form of weaving basket for cats.

Amongst the more well-known types are:[8]

- Hakoneyosegizaiku (箱根寄木細工), wooden marquetry from Hakone, Ashigarashimo district, and Odawara, Kanagawa prefecture

- Iwayadotansu (岩谷堂箪笥), wooden chests of drawers, from Oshu, Iwate prefecture

Metalwork

Early Japanese iron-working techniques date back to the 3rd to 2nd century BCE. Japanese swordsmithing is of extremely high quality and greatly valued. These swords originated before the 1st century BCE and reached their height of popularity as the chief possession of warlords and samurai. The production of a sword has retained something of the religious quality it once had in symbolizing the soul of the samurai and the martial spirit of Japan. Swordsmithing is considered a separate art form and moved beyond the craft it once started out as.

Items for daily use were also made out of metal and a whole section of craft developed around it.

Casting is creating the form by melting. The techniques include:[9]

- Rogata (蝋型)

- Sogata (惣型)

- Komegata (込型)

Another form is smithing (鍛金), which is creating forms by beating.

And the most important japanese technique is forge welding(鍛接), which is a type of welding to join iron and carbon steel. The technique is used to make a cutlery such as chisel and plane. One of the most famous producing erea is Yoita, Nagaoka City, Niigata Prefecture, and it is called "Echigo Yoita Uchihamono"(越後与板打刃物).

To create various patterns on the surface, metal carving is used to apply decorative designs. The techniques include carving (彫り), metal inlay (象嵌), and embossing (打ち出し).[9]

Amongst the more well-known types are:[9]

- Nambutekki (南部鉄器), ironware from Morioka and Oshu, Iwate prefecture

- Takaoka Doki (高岡銅器), copperware from Takaoka, Toyama prefecture

Dolls

There are various types of traditional Japanese dolls (人形, ningyō, lit. "human form"), some representing children and babies, some the imperial court, warriors and heroes, fairy-tale characters, gods and (rarely) demons, and also people of the daily life of Japanese cities. Many have a long tradition and are still made today, for household shrines, for formal gift-giving, or for festival celebrations such as Hinamatsuri, the doll festival, or Kodomo no Hi, Children's Day. Some are manufactured as a local craft, to be purchased by pilgrims as a souvenir of a temple visit or some other trip.

There are four different base materials used to make dolls:[10]

- Wooden dolls (木彫人形)[11]

- Toso dolls (桐塑人形), made out of toso, a substance made out of paulownia sawdust mixed with paste that creates a clay-like substance[12]

- Harinuki dolls (張抜人形), made out of papier-mache[13]

- Totai dolls (陶胎人形), made out of ceramic[14]

The painting or application techniques are:[10]

- Nunobari (布貼り)

- Kimekomi (木目込み)[15]

- Hamekomi (嵌込み)[16]

- Kamibari (紙貼り)[17]

- Saishiki (彩色)[18]

- Saicho (彩彫)[19]

Known types are, for example, Hakata ningyō (博多人形).[20]

Paper making

The Japanese art of making paper from the mulberry plant called washi (和紙) is thought to have begun in the 6th century. Dyeing paper with a wide variety of hues and decorating it with designs became a major preoccupation of the Heian court, and the enjoyment of beautiful paper and its use has continued thereafter, with some modern adaptations. The traditionally made paper called Izumo (after the shrine area where it is made) was especially desired for fusuma (sliding panels) decoration, artists' papers, and elegant letter paper. Some printmakers have their own logo made into their papers, and since the Meiji period, another special application has been western marbleized end papers (made by the Atelier Miura in Tokyo).

Others

Glass

The tradition of glass production goes back far in history into the Kofun period, but was used very rarely and more for decorative purposes such as being included in hair needles. Only relatively late in the Edo period did it experience increased popularity and with the beginning of modernisation during the Meiji era did large-scale industrial production of glassware commence. Nevertheless, glassware continues to exist as a craft – for example Edo kiriko (江戸切子) and Satsuma kiriko (薩摩切子). The various techniques used are:[21]

- Glassblowing (吹きガラス)

- Cut glass (切子)

- Gravure (グラヴィール)

- Pâte de verre (パート・ド・ヴェール)

- Enameling (エナメル絵付け)

Cloisonné

Cloisonné (截金, shippō) is a glass-like glaze that is applied on a metal framework, and then fired in a kiln.[21] It developed especially in Owari province around Nagoya in the late Edo period and going into the Meiji era. One of the leading traditional producing companies that still exists is the Ando Cloisonné Company.

Techniques of shippō include:

Gem carving

Gem carving (砡, gyoku) is carving naturally patterned agate or various hard crystals into tea bowls and incense containers.[25]

Decorative metal cutting

Kirikane (截金) is a decorative technique used for paintings and Buddhist statues, which applies gold leaf, silver leaf, platinum leaf cut into geometric patterns of lines, diamonds and triangles.[21]

Inkstone carving

Calligraphy is considered one of the classical refinements and art forms. The production on inkstone was therefore greatly valued.[21]

See also

- Intangible Cultural Properties of Japan for a full listing of protected crafts on the national, prefectural, and municipal levels

- Japanese dolls

- Meibutsu

References

- http://wsimag.com/architecture-and-design/4457-shippo-cloisonne-radiance-of-japan

- http://ichinen-fourseasonsinjapan.blogspot.ch/2016/09/the-63rd-japan-traditional-kogei.html

- http://madmuseum.org/exhibition/japanese-k%C5%8Dgei-future-forward

- http://www.architecturaldigest.com/gallery/japanese-kogei-future-forward-mad-museum/all

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/ceramics/

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/textiles/

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/urushiwork/

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/wood-bamboowork/

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/metalwork/

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/dolls/

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/dolls/60101/

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/dolls/60102/

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/work/list/?subject_category=6&technique_category=60105

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/work/list/?subject_category=6&technique_category=60106

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/work/list/?subject_category=6&technique_category=60202

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/work/list/?subject_category=6&technique_category=60204

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/work/list/?subject_category=6&technique_category=60206

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/work/list/?subject_category=6&technique_category=60207

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/work/list/?subject_category=6&technique_category=60208

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/dolls/hakataningyo/

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/otherwork/

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/work/list/?subject_category=7&technique_category=70101

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/work/list/?sort=2&subject_category=7&technique_category=70104

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/work/list/?sort=2&subject_category=7&technique_category=70103

- http://galleryjapan.com/locale/en_US/technique/otherwork/70304/

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/. – Japan

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/. – Japan

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crafts of Japan. |