Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 227

Jesu, meine Freude (Jesus, my joy), BWV 227, is a motet in eleven movements for SSATB choir which was composed by Johann Sebastian Bach. It is named after the Lutheran hymn "Jesu, meine Freude", of which it contains, in its uneven movements, all six stanzas of Johann Franck's poetry and various versions of Johann Crüger's hymn tune. The text of the motet's even movements is taken from the Epistle to the Romans. The Biblical text, which contains key Lutheran teaching, is contrasted by the hymn, written in the first person with a focus on emotion, and Bach set both with attention to dramatic detail in a symmetrical structure. The composition is in E minor. Bach's treatment of the chorale tune ranges from a four-part setting which begins and ends the work, to a chorale fantasia and a free setting which only paraphrases the tune. Four verses from the Epistle are set in motet style, two for five voices, and two for three voices. The central movement is a five-part fugue. Bach used word painting to intensify the theological meaning of both hymn and Epistle texts.

| Jesu, meine Freude | |

|---|---|

BWV 227 | |

| Motet by J. S. Bach | |

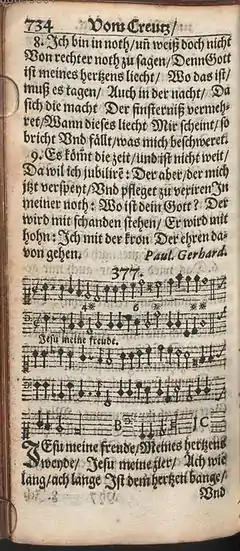

_Anfangstakte.png.webp) Beginning of the first movement | |

| Key | E minor |

| Bible text | Romans 8:1–2,9–11 |

| Chorale | |

| Movements | 11 |

| Vocal | SSATB five-part choir |

| Instrumental | lost colla parte? |

Jesu, meine Freude is one of the few works by Bach for five vocal parts. It may have been composed for a funeral, but scholars doubt a 1912 dating to a specific funeral in Leipzig on 18 July 1723, a few months after Bach had moved to Leipzig. Chorale settings from the motet were included in the Dietel manuscript, which dates from around 1735. At least one of the eleven movements seems to have been composed before Bach's tenure in Leipzig. Christoph Wolff suggested that the motet may have been composed for education in both choral singing and theology. Unique in its complex symmetrical structure juxtaposing hymn text and Bible text, it has been regarded as one of Bach's greatest motets.[1] It was the first of his motets to be recorded, in 1927.

History

Members of the Bach family of the generations before Johann Sebastian wrote motets in late 17th-century Protestant Germany. Several of these motets are preserved in the Altbachisches Archiv (ABA). In that context, motets are choral compositions, mostly with a number of independent voices exceeding that of a standard SATB choir of soprano, alto, tenor and bass and with a German text from sacred scripture and/or based on a Lutheran hymn. In the latter case, the corresponding chorale tune was usually adopted into the composition. Instrumental accompaniment was often limited to basso continuo and/or instruments playing colla parte. By the time Bach started to compose his motets in the 1710s or 1720s along the principles of these older compositions, motets were regarded as an antiquated genre. According to Philipp Spitta, Bach's 19th-century biographer, Johann Michael Bach's motet Halt, was du hast, ABA I, 10, which contains a setting of the "Jesu, meine Freude" chorale, may have been on Johann Sebastian's mind when he composed his motet named after the chorale, in E minor like his ancestor's.[2][3]

In Bach's time, the Lutheran liturgical calendar of the place where he lived indicated the occasions for which figural music was required. The bulk of the composer's sacred music, including almost all of his church cantatas, was written for such occasions. His other church music, such as sacred cantatas for weddings and funerals, and most, if not all, of his motets, was not tied to the liturgical calendar.[1] Among around 15 extant compositions which at some point or another were designated as a motet by Bach (BWV 118, 225–231, 1083, 1149, Anh. 159–165),[4][5][6][7] Jesu, meine Freude is one of only five (BWV 225–229) which, without exception, have always been considered as belonging in that category.[8] In eleven movements, Jesu, meine Freude is the longest and most musically complex of Bach's motets.[9][10] It is scored for SSATB voices.[11] Bach composed only very few works for a five-part choir: most of his other motets are for double SATB choir, while the large majority of his vocal church music is to be performed with one SATB choir.[8] Like for most of his other motets, no continuo or other instrumental accompaniment has survived for BWV 227, but it is surmised there used to be one.[11][12]

Epistle text and chorale

The text of Jesu, meine Freude is compiled from two sources, the 1653 hymn of the same name with words by Johann Franck, and Bible verses from the Epistle to the Romans, 8:1–2 and 9–11.[13] In the motet, the six hymn stanzas form the odd movement numbers, while the even numbers each take one verse from the Epistle as their text.[13] The hymn's first line, which Catherine Winkworth translated as "Jesu, priceless treasure" in 1869,[14] is repeated as the last line of its last stanza, framing the poetry.[15]

Johann Crüger's chorale melody for the hymn, Zahn 8032, was published for the first time in his Praxis pietatis melica of 1653, after which several variants of the hymn tune were published in other hymnals over the ensuing decades.[16] The tune is in bar form.[16][17] In the version of Vopelius's Neu Leipziger Gesangbuch of 1682, the hymnal used in Leipzig, the melody of the first line is the same as that of the last line.[16][18][17] The hymn tune appears in several variants in the uneven movements of the motet.[19]

As a key teaching of the Lutheran faith, the Gospel text reflects on Jesus Christ freeing man from sin and death, focused on the contrast of living "in the flesh" or "according to the Spirit".[20] The hymn text is written from an individual believer's point of view, addressing Jesus as joy and support, against enemies and the vanity of existence, which are expressed in stark images. The hymn adds a layer of individuality and emotions to Biblical teaching.[21]

Time of origin

Most of Bach's motets are difficult to date, and Jesu, meine Freude is no exception.[22][23] Spitta, Bach's early biographer, assigned the motets, including Jesu, meine Freude, to Bach's Leipzig years.[24] In 1912, Bernhard Friedrich Richter wrote that Jesu, meine Freude was likely written in Bach's first year as Thomaskantor in Leipzig, for the funeral of Johanna Maria Kees, the wife of the Leipzig postmaster, on 18 July 1723, because a scripture reading of verse 11 from the Epistle passage set in the motet, in the tenth movement, is documented for the funeral.[25][26] The Cambridge musicologist Daniel R. Melamed wrote in his 1995 book about Bach's motets that this is not conclusive evidence for a motet performance, but that the date was still "nearly universally accepted".[25] The order of that particular service was found in 1982, mentioning neither a motet nor even the chorale.[25]

Friedrich Smend was the first to analyse the motet's symmetrical structure, a feature which can also be found in Bach's St John Passion of 1724 and St Matthew Passion of 1727, which led Smend to suggest that the work was composed in the 1720s.[27] Looking at the four-part settings of the chorale movements 1, 7 and 11, which seem unusual for a five-part work, and at the older version of the chorale melody used as the cantus firmus in the ninth movement, which suggests an origin of that movement in Bach's Weimar period, or even earlier, Melamed thought that the motet was likely in part compiled from music Bach had composed before his Leipzig period.[19]

Christoph Wolff suggested that the motet might be intended not for a funeral but the education of the Thomanerchor, as also Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, BWV 225.[28] According to Richard D. P. Jones, several movements of the motet show a style too advanced to have been written in 1723, so that the final arrangement of the work likely happened in the late 1720s, around the time when two other motets which can be dated with more certainty, Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied and the funeral motet Der Geist hilft unser Schwachheit auf, BWV 226, were written.[29] The Dietel manuscript, written around 1735, contains three chorales extracted from the motet: the composition of the motet is supposed to have been completed before that time.[11][30]

Structure and scoring

The motet is structured in eleven movements, with text alternating a chorale stanza and a passage from the Epistle.[13] Bach scored it for a choir of two soprano parts (S or SS), alto (A), tenor (T), and bass (B). The number of voices in the movements varies from three to five. Only the alto, the middle voice in the motet's SSATB setting, sings in all movements. The motet was possibly meant to be accompanied by instruments playing colla parte in the practice at the time,[8] but no parts for them survived.[11]

The music is arranged in different layers of symmetry around the sixth movement.[31] The first and last movements are the same four-part setting of two different hymn stanzas (indicated with stanza numbers 1 and 6 in the diagram below). The second (Rom. 8:1) and penultimate (Rom. 8:11) movements use the same themes in fugal writing. The third (stanza 2) and fifth (stanza 3) movements, both five-part, mirror the seventh (stanza 4) and ninth (stanza 5) movements, both four-part. The fourth (Rom. 8:2) and eighth (Rom. 8:10) movements are both trios, the fourth for the three highest voices, the other for the three lowest voices. The central movement (Rom. 8:9) is a five-part fugue.[32][33]

| 1 chorale SATB (same as 11) |

Epistle Rom. 8:1 SSATB (similar to 10) |

|

Epistle Rom. 8:9 SSATB fugue |

|

Epistle Rom. 8:11 SSATB (similar to 2) |

6 chorale SATB (same as 1) |

Movements

In the following table, the movement number is followed by the beginning of the text, its source, the voices, and key and time signatures.

| No. | Title | Text source | Voices | Key | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jesu, meine Freude | verse 1 | SATB | E minor | |

| 2 | Es ist nun nichts Verdammliches | Romans 8:1 | SSATB | E minor | 3/2 |

| 3 | Unter deinen Schirmen | verse 2 | SSATB | E minor | |

| 4 | Denn das Gesetz | Romans 8:2 | SSA | G major | 3/4 |

| 5 | Trotz dem alten Drachen | verse 3 | SSATB | E minor | 3/4 |

| 6 | Ihr aber seid nicht fleischlich | Romans 8:9 | SSATB | G major | |

| 7 | Weg, weg mit allen Schätzen | verse 4 | SATB | E minor | |

| 8 | So aber Christus in euch ist | Romans 8:10 | ATB | C major | 12/8 |

| 9 | Gute Nacht, o Wesen | verse 5 | SSAT | A minor | 2/4 |

| 10 | So nun der Geist | Romans 8:11 | SSATB | E minor | 3/2 |

| 11 | Weicht, ihr Trauergeister | verse 6 | SATB | E minor |

1

The motet begins with a four-part setting of the first stanza of the hymn[34] "Jesu, meine Freude" (Jesus, my joy).[13][35] This and most other movements related to the hymn are in E minor. The text, in the first person, speaks of longing for Jesus.[13] Jones noted that the tenor part is particularly expressive.[29] The last movement has exactly the same music to the different text of the last stanza, creating a frame which encloses the whole work:[29]

2

The second movement begins with excerpts from the Epistle to the Romans with "Es ist nun nichts Verdammliches an denen, die in Christo Jesu sind" (Now there is nothing damnable in those who are in Christ Jesus).[13] The difference of living in the flesh and the spirit is an aspect that will be repeated throughout the motet.[13] The movement is also in E minor, but for five voices.[36] The text is rendered first in rhetorical homophony.[29]

In setting the first sentence, Bach accented the word "nichts" (nothing), repeating it twice, with long rests and echo dynamics. Jones noted that dramatic word painting of this kind was in the tradition of 17th-century motets, such as by Johann Christoph Bach and Johann Michael Bach.[37]

3

The third movement is a five-part setting of the second stanza of the hymn,[38] "Unter deinen Schirmen bin ich für den Stürmen aller Feinde frei" (Under your protection I am safe from the storms of all enemies).[13][39] While the soprano provides the chorale melody, the lower voices supply vivid lines expressing the text.[29]

4

The fourth movement sets the second verse from the Epistle, "Denn das Gesetz des Geistes, der da lebendig machet in Christo Jesu, hat mich frei gemacht von dem Gesetz der Sünde und des Todes" (For the law of the spirit, which gives life in Christ Jesus, has made me free from the law of sin and death).[13] The thought is set for the two sopranos and alto, beginning in G major.[40] The sopranos often move in "beatific" third parallels.[37]

5

The fifth movement is a setting of the third stanza of the hymn,[41] "Trotz dem alten Drachen" (Defiance to the old dragon).[13] The defiant opposition, also to death, fear and the rage of the world, is expressed in a free composition. The soprano melody quotes short motifs from the chorale, while keeping the bar form of the original melody.[3][29] Five voices take part in dramatic illustration of defiance, in the same rhetorical style as the beginning of the second movement,[29] here often expressed in powerful unison.[29] The voices also depict standing firmly and singing, again in rhetorical homophony and reinforced in unison.[42] John Eliot Gardiner noted that the firm stance against opposition could depict Martin Luther's attitude and also the composer's own stance.[43]

6

The central sixth movement sets verse 9 from the Epistle, "Ihr aber seid nicht fleischlich, sondern geistlich" (You, however, are not of the flesh, but rather of the Spirit).[13] Again beginning in G major, the tenor begins with a fugue theme that stresses the word "geistlich" (of the Spirit) by a long melisma in fast notes, while the opposite "fleischlich" is a long note stretched over the bar-line.[33] The alto enters during the melisma. All five voices participate in a lively fugue,[44] the only one within the motet.[29] It is a double fugue, with a first theme for the first line, another for the second,[37] "so anders Gottes Geist in euch wohnet" (since the Spirit of God lives otherwise in you),[13] and then both combined [37] in various ways, parallel and in stretti. By contrast, the third line of verse 9, "Wer aber Christ Geist nicht hat, der ist nicht sein" (Any one who does not have the spirit of Christ does not belong to him) is set in a homophonic adagio with deeply unsettling harmonies: "not of Christ".

7

The seventh movement is a four-part setting of the fourth stanza of the hymn,[45] "Weg mit allen Schätzen" (Away with all treasures).[13] While the soprano sings the chorale melody, the lower voices intensify the gesture dramatically: "weg" is repeated several times in fast succession.[45][46] Throughout the movement, the lower voices intensify the expressiveness of the text.[29]

8

The eighth movement sets verse 10 from the Epistle, "So aber Christus in euch ist, so ist der Leib zwar tot um der Sünde willen; der Geist aber ist das Leben um der Gerechtigkeit willen" (However if Christ is in you, then the body is dead indeed for the sake of sin; but the spirit is life for the sake of righteousness).[13] As in the fourth movement, it is set as a trio, this time for alto, tenor and bass, beginning in C major.[47] Third parallels in the upper voices resemble those in the fourth movement.[37]

9

The ninth movement is a setting of the fifth stanza of the hymn,[48] "Gute Nacht, o Wesen, das die Welt erlesen" (Good night, existence that cherishes the world).[13] For the rejection of everything earthly, Bach composed a chorale fantasia, with the cantus firmus in the alto voice and two sopranos and tenor repeating "Gute Nacht" often.[49] Jones pointed out that the absence of a bass may depict that "the world" lacks a firm foundation in Christ.[50] The chorale melody used in this movement is slightly different from the one in the other settings within the motet,[51] a version which Bach used mostly in his earlier time in Weimar and before.[19] For Gardiner, the "sublime" music suggests the style of Bach's Weimar period.[52]:10 Jones, however, found that the "bewitchingly lyrical setting" matched compositions from the mid-1720s in Leipzig,[53] comparing the music to the Sarabande from the Partita No. 3, BWV 827.[51]

10

The tenth movement sets verse 11 from the Epistle, "So nun der Geist des, der Jesum von den Toten auferwecket hat, in euch wohnet" (So now the spirit that awakened Jesus from the dead dwells in you).[13] In symmetry, the music recalls that of the second movement.[54]

11

The motet ends with the same four-part setting as the first movement, now with the text of the last stanza of the hymn,[55] "Weicht, ihr Trauergeister" (Hence, you spirits of sadness).[13][35] The final line repeats the beginning, on the same melody: "Dennoch bleibst du auch im Leide, / Jesu, meine Freude" (You stay with me even in sorrow, / Jesus, my joy).[13]

Reception

The structure of Jesu, meine Freude has been regarded as unique in its complex symmetrical structure juxtaposing hymn text and Bible text.[56] Bach's vivid setting of the contrasting texts, even illustrating single words, results in music of an unusual dramatic range.[57] Wolff summarised:

This diversified structure of five-, four-, and three-part movements, with shifting configurations of voices and a highly interpretive word-tone relationship throughout, wisely and sensibly combines choral exercise with theological education.[28]

Performers of Jesu, meine Freude have to decide if they will use a boys' choir (as Bach had in mind) or a mixed choir, a small vocal ensemble or a larger choir, a continuo group, and instruments playing colla parte.[58][59]

18th and 19th centuries

As for most of Bach's motets, there is no extant autograph of Jesu, meine Freude. The motet's SATB chorales were copied in several 18th-century manuscripts collecting chorale harmonisations by Bach.[60][61] The earliest extant of such chorale collections, the Dietel manuscript, also contains a SATB version of the motet's five-part third movement: Dietel's copy omitted the second soprano part of that movement.[30][62][63] Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach retained the two other chorales, based on the motet's first (=11th) and seventh movements, in the third volume of Breitkopf's 1780s edition of Bach's four-part chorales.[35][46][60][61]

After Bach's death, the motets, unlike much of his other music, were kept continuously in the repertoire of the Thomanerchor.[64] A choral version of the entire motet, that is without any indication of instrumental accompaniment, was first published in 1803, in the second volume of Breitkopf & Härtel's first edition of six motets by (or at least, attributed to) Bach.[65][66] Together with other motets edited by Franz Wüllner, Jesu, meine Freude was published in 1892 in volume 39 of the Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe (BGA).[67]

20th and 21st centuries

In the 1920s, the large Bach Choir in London performed Bach's works conducted by Ralph Vaughan Williams, while Charles Kennedy Scott performed Jesu, meine Freude with his Bach Cantata Club in chamber formation, which prompted a reviewer to write:

It would be absurd to forbid Bach's Motets to big choirs, but this performance left no doubt that the listener gets the truth of the music from voices few and picked.[68]

Scott and the Bach Cantata Club made the first recording of it, which was the first of any motet by Bach, in 1927, sung in English.[69]

The New Bach Edition (Neue Bach-Ausgabe, NBA) published the motet in 1965, edited by Konrad Ameln, with critical commentary published in 1967.[11] In 1995, Bärenreiter published the vocal parts of the six motets BWV 225–230 from the NBA in one volume, with a preface by Klaus Hofmann.[64] The motets were published by Carus-Verlag in 1975, edited by Günter Graulich, and again in 2003, edited by Uwe Wolf, as part of the Stuttgarter Bach-Ausgaben, a complete edition of Bach's vocal works.[70] Modern editions of the motet may supply a reconstructed instrumental accompaniment, such as a continuo realisation, and/or a singable translation of the lyrics, as for instance in Carus's 2003 publication of the motet.[71]

Jesu, meine Freude has been recorded more than 60 times, mostly in combination with other motets by Bach.[72] These recorded sets of motets are partially listed at Motets by Johann Sebastian Bach, discography and include:

- Philippe Herreweghe with the Collegium Vocale Gent and La Chapelle Royale, 1985

- Harry Christophers with The Sixteen, 1989

- Masaaki Suzuki with the Bach Collegium Japan, using instruments playing colla parte, 2009[1]

- Philippe Herreweghe, second set recorded in 2010.[73]

References

- Cookson 2010.

- Schneider 1935, 1: Motetten und Chorlieder.

- Spitta 1899, p. 601.

- Dürr & Kobayashi 1998, pp. 228–233, 459, 467.

- "D-B Mus.ms. 30199, Fascicle 14". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 2020-01-31.

- Der Gerechte kömmt um BWV deest (BC C 8) at Bach Digital.

- Instrumental and Supplement at www

.bach333 , p. 127.com - Jones 2013, p. 198.

- Ameln 1965.

- Robins 2020.

- Jesu, meine Freude BWV 227 at Bach Digital.

- Melamed 1995.

- Dellal 2020.

- CCEL 2020.

- Hymnary text 2020.

- Zahn 1891, p. 651.

- Hymnary tune 2020.

- Vopelius 1682, p. 780.

- Melamed 1995, pp. 86–87.

- May 2020.

- Schmidt 2011.

- Melamed 1995, p. 98.

- Wolf (score) 2002, p. V.

- Melamed 1995, pp. 85, 98.

- Melamed 1995, p. 85.

- Hofmann 1995, p. IV.

- Melamed 1995, p. 86.

- Wolff 2002, p. 249.

- Jones 2013, p. 203.

- Wolff 2002, p. 329.

- Jones 2013, pp. 202–203.

- Posner 2020.

- Gardiner 2013, p. 351.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, p. 2.

- Dahn 1 2018.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, p. 4.

- Jones 2013, p. 205.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, p. 13.

- Dahn 3 2018.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, p. 15.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, p. 16.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, pp. 16–22.

- Gardiner 2013, p. 352.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, pp. 22–28.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, p. 30.

- Dahn 7 2018.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, p. 33.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, p. 36.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, pp. 36–41.

- Jones 2013, pp. 203–204.

- Jones 2013, pp. 204–205.

- Gardiner 2012.

- Jones 2013, pp. 204.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, pp. 42–45.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003, p. 46.

- Jones 2013, p. 202.

- Eckerson 2020.

- Wolf (score) 2002, p. VII.

- Veen 2010.

- Jesu, meine Freude BWV 227/1 at Bach Digital.

- Jesu, meine Freude BWV 227/7 at Bach Digital.

- Jesu, meine Freude BWV 227/3 at Bach Digital.

- Schulze 1983, p. 91.

- Hofmann 1995, p. VII.

- Melamed 1995, p. 99.

- Wolf (article) 2002, p. 269.

- Dürr & Kobayashi 1998, pp. 229–230.

- Haskell 1996, p. 38.

- Elste 2000.

- Wolf (score) 2002, p. I.

- Graulich & Wolf 2003.

- ArkivMusic 2020.

- Riley 2012.

Cited sources

- "Der Gerechte kömmt um BWV deest (BC C 8)". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 2019-05-25.

- "Jesu, meine Freude BWV 227". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 2019-05-14.

- "Jesu, meine Freude BWV 227/1". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 2019-05-23.

- "Jesu, meine Freude BWV 227/3". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 2019-05-23.

- "Jesu, meine Freude BWV 227/7". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 2019-05-23.

Books

- Ameln, Konrad (1965). Bach, Johann Sebastian / Jesu, meine Freude for Five-part Mixed Choir in E minor BWV 227. Bärenreiter. ISMN 979-0-00-649848-2. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Dürr, Alfred; Kobayashi, Yoshitake, eds. (1998). Bach Werke Verzeichnis: Kleine Ausgabe – Nach der von Wolfgang Schmieder vorgelegten 2. Ausgabe [Bach Works Catalogue: Small Edition – After Wolfgang Schmieder's 2nd edition] (in German). Kirsten Beißwenger (collaborator). (BWV2a ed.). Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel. ISBN 9783765102493. Preface in English and German.

- Gardiner, John Eliot (2013). Music in the Castle of Heaven: A Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach. Penguin UK. pp. 350–352. ISBN 978-1-84-614721-0.

- Graulich, Günter; Wolf, Uwe, eds. (2003). Johann Sebastian Bach: Jesu, meine Freude / Jesus, My Salvation – BWV 227 (PDF) (Urtext, full score). Stuttgarter Bach-Ausgaben (in German and English). Translated by Lunn, Jean. Continuo realisation by Horn, Paul. Carus. CV 31.227.

- Haskell, Harry (1996). The Early Music Revival: A History. Courier Corporation. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-48-629162-8.

- Hofmann, Klaus (1995). "Preface". J. S. Bach / Motetten / Motets. Bärenreiter. pp. VII–IX. ISMN 979-0-00-649848-2

- Jones, Richard D. P. (2013). The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume II: 1717–1750: Music to Delight the Spirit. Oxford University Press. pp. 202–205. ISBN 978-0-19-969628-4.

- Melamed, Daniel R. (1995). Chronology, Style, and Performance Practise of Bach's Motets. J. S. Bach and the German Motet. Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–106. ISBN 978-0-52-141864-5.

- Schneider, Max, ed. (1935). Altbachisches Archiv: aus Johann Sebastian Bachs Sammlung von Werken seiner Vorfahren Johann, Heinrich, Georg Christoph, Johann Michael u. Johann Christoph Bach [Old-Bachian Archive: From Johann Sebastian Bach's Collection of Works by His Forefathers Johann, Heinrich, Georg Christoph, Johann Michael and Johann Christoph Bach]. Vol. I of Das Erbe deutscher Musik (in German). 1: Motetten und Chorlieder (Motets and choral songs) – 2: Kantaten (Cantatas). Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. Reprint: 1966.

- Spitta, Philipp (1899). Johann Sebastian Bach: His Work and Influence on the Music of Germany, 1685–1750. II. Translated by Bell, Clara; Fuller Maitland, John Alexander. Novello & Co.

- Vopelius, Gottfried (1682). Neu Leipziger Gesangbuch [New Leipzig hymnal] (in German). Christoph Klinger.

- Wolf, Uwe (2002). "Zur Schichtschen Typendruck-Ausgabe der Motetten Johann Sebastian Bachs und zu ihrer Stellung in der Werküberlieferung" [On Schicht's movable font edition of the motets of Johann Sebastian Bach, and on its place in the work transmission]. Musikalische Quellen, Quellen zur Musikgeschichte: Festschrift für Martin Staehelin zum 65. Geburtstag [Musical sources, sources for the history of music: commemorative paper for Martin Staehelin's 65th birthday] (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 269–286. ISBN 978-3-52-527820-8.

- Wolf, Uwe, ed. (2002). "Preface". Johann Sebastian Bach / Motetten / Motets (PDF) (Urtext, full score). Stuttgarter Bach-Ausgaben (in German and English). Translated by Coombs, John. Carus. CV 31.224.

- Wolff, Christoph (2002). Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician. Oxford University Press. pp. 278–279. ISBN 978-0-393-32256-9.

- Zahn, Johannes (1891). Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder [The melodies of the German evangelical hymns] (in German). IV. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann.

Journals

- Riley, Paul (2012). "Bach, JS: Motets BWV 225-230". BBC Music Magazine. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Schmidt, Eckart David (1 December 2011). "'Jesu, meine Freude'. Zu einer theologischen und pragmatischen Hermeneutik von Text und Musik in J. S. Bachs Motette BWV 227" ['Jesu, meine Freude': On a theological and practical hermeneutics of text and music of J. S. Bach's motet BWV 227]. International Journal of Practical Theology (in German). De Gruyter. 15 (2). doi:10.1515/IJPT.2011.034. S2CID 146854834. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Schulze, Hans-Joachim (1983). "'150 Stücke von den Bachischen Erben': Zur Überlieferung der vierstimmigen Choräle Johann Sebastian Bachs" ["150 pieces from the Bach estate": on the transmission of Johann Sebastian Bach's four-part chorales]. In Schulze, Hans-Joachim; Wolff, Christoph (eds.). Bach-Jahrbuch 1983 [Bach Yearbook 1983]. Bach-Jahrbuch (in German). 69. Neue Bachgesellschaft. Berlin: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt. pp. 81–100. doi:10.13141/bjb.v1983. ISSN 0084-7682.

Online sources

- Cookson, Michael (May 2010). "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) / Motets". musicweb-international.com. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Dahn, Luke (2018). "BWV 227.1=227.11". bach-chorales.com. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Dahn, Luke (2018). "BWV 227.3". bach-chorales.com. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Dahn, Luke (2018). "BWV 227.7". bach-chorales.com. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Dellal, Pamela (2020). "BWV 227 - "Jesu, meine Freude"". Emmanuel Music. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Eckerson, Sara (2020). "On J. S. Bach's Sublime 'Gute Nacht' of Jesu, meine Freude (BWV 227)". Forma de Vida. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Elste, Martin (2000). "Die Motetten BWV 225–230 und 118." [The motets BWV 225–230 and 118]. Meilensteine der Bach-Interpretation 1750–2000 (in German). J. B. Metzler. pp. 176–179. doi:10.1007/978-3-476-03792-3_16. ISBN 978-3-476-01714-7.

- Gardiner, John Eliot (2012). "Bach Motets" (PDF). mStuttgartonteverdi.org.uk. pp. 6, 10–11. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- May, Thomas (2020). ""Let All That Have Breath Praise": The Motets of J.S. Bach". Los Angeles Master Chorale. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Posner, Howard (2020). "Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 227 / Johann Sebastian Bach". Los Angeles Philharmonic. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Robins, Brian (2020). "Johann Sebastian Bach / Jesu, meine Freude, motet for 5-part chorus, BWV 227 (BC C5)". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Veen, Johan van (2010). "CD reviews / Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750): Motets". musica-dei-donum.org. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Composition Type: Sacred Music / Work: Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 227". arkivmusic.com. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Jesu, meine Freude, meines Herzens Weide". hymnary.org. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Jesu, meine Freude". ccel.org. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "Jesu, meine Freude". hymnary.org. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to BWV 227 – Motet "Jesu, meine Freude". |

- Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 227: performance by the Netherlands Bach Society (video and background information)

- Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 227 (Bach, Johann Sebastian): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 227: Free scores at the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Literature about Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 227 in the German National Library catalogue

- Johann Gottfried Schicht (ed.): Joh. Seb. Bach's Motetten in Partitur. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel. 1802 (Vol. 1: BWV 225, 228, Anh. 159); 1803 (Vol. 2: BWV 229, 227, 226)

- Recording of Jesu, meine Freude in MP3 format from Umeå Akademiska Kör