Jojoba

Jojoba /həˈhoʊbə/ (![]() listen), with the botanical name Simmondsia chinensis, and also known as goat nut, deer nut, pignut, wild hazel, quinine nut, coffeeberry, and gray box bush,[2] is native to the Southwestern United States. Simmondsia chinensis is the sole species of the family Simmondsiaceae, placed in the order Caryophyllales.

listen), with the botanical name Simmondsia chinensis, and also known as goat nut, deer nut, pignut, wild hazel, quinine nut, coffeeberry, and gray box bush,[2] is native to the Southwestern United States. Simmondsia chinensis is the sole species of the family Simmondsiaceae, placed in the order Caryophyllales.

| Jojoba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis) shrub | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Simmondsiaceae |

| Genus: | Simmondsia Nutt. |

| Species: | S. chinensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Simmondsia chinensis | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

List

| |

Jojoba is grown commercially to produce jojoba oil, a liquid wax ester extracted from its seed.

Distribution

The plant is a native shrub of the Sonoran Desert,[3] Colorado Desert, Baja California Desert, and California chaparral and woodlands habitats in the Peninsular Ranges and San Jacinto Mountains. It is found in southern California, Arizona, and Utah (U.S.), and Baja California state (Mexico).

Jojoba is endemic to North America, and occupies an area of approximately 260,000 square kilometers (100,000 sq mi) between latitudes 25° and 31° North and between longitudes 109° and 117° West.[3]

Description

Simmondsia chinensis, or jojoba, typically grows to 1–2 meters (3.3–6.6 ft) tall, with a broad, dense crown, but there have been reports of plants as tall as 3 meters (9.8 ft).[3]

The leaves are opposite, oval in shape, 2–4 centimeters (0.79–1.57 in) long and 1.5–3 centimeters (0.59–1.18 in) broad, thick, waxy, and glaucous gray-green in color.

The flowers are small and greenish-yellow, with 5–6 sepals and no petals. The plant typically blooms from March to May.[4]

Reproduction

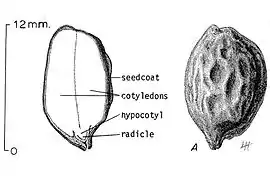

Each plant is dioecious, with hermaphrodites being extremely rare. The fruit is an acorn-shaped ovoid, three-angled capsule 1–2 centimeters (0.39–0.79 in) long, partly enclosed at the base by the sepals. The mature seed is a hard oval that is dark brown and contains an oil (liquid wax) content of approximately 54%. An average-sized bush produces 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) of pollen, to which few humans are allergic.[2]

The female plants produce seed from flowers pollinated by the male plants. Jojoba leaves have an aerodynamic shape, creating a spiral effect, which brings wind-born pollen from the male flower to the female flower. In the Northern Hemisphere, pollination occurs during February and March. In the Southern Hemisphere, pollination occurs during August and September.

Somatic cells of jojoba are tetraploid; the number of chromosomes is 2n = 4x = 52.[5]

Female flower

Female flower Close-up of male Simmondsia chinensis flowers

Close-up of male Simmondsia chinensis flowers Jojoba fruits

Jojoba fruits Jojoba seed

Jojoba seed

Genetics

The jojoba genome was sequenced in 2020 and reported to be 887-Mb, consisting of 26 chromosomes (2n = 26), and is predicted to have 23,490 protein-coding genes.[6]

Taxonomy

Despite its scientific name Simmondsia chinensis, the plant is not native to China. The botanist Johann Link originally named the species Buxus chinensis, after misreading a collection label "Calif", referring to California, as "China". Jojoba was collected again in 1836 by Thomas Nuttall who described it as a new genus and species in 1844, naming it Simmondsia californica, but priority rules require that the original specific epithet be used.

The common name "jojoba" originated from O'odham name Hohowi.[2] The common name should not be confused with the similarly written jujube (Ziziphus zizyphus), an unrelated plant species, which is commonly grown in China.

Uses

Jojoba foliage provides year-round food for many animals, including deer, javelina, bighorn sheep, and livestock. Its nuts are eaten by squirrels, rabbits, other rodents, and larger birds.

Only Bailey's pocket mouse, however, is known to be able to digest the wax found inside the jojoba nut. In large quantities, jojoba seed meal is toxic to many mammals, later this effect was found to be due to simmondsin, which inhibits hunger. The indigestible wax acts as a laxative in humans.

Native American uses

Native Americans first made use of jojoba. During the early 18th century Jesuit missionaries on the Baja California Peninsula observed indigenous peoples heating jojoba seeds to soften them. They then used a mortar and pestle to create a salve or buttery substance. The latter was applied to the skin and hair to heal and condition. The O'odham people of the Sonoran Desert treated burns with an antioxidant salve made from a paste of the jojoba nut.[2]

Native Americans also used the salve to soften and preserve animal hides. Pregnant women ate jojoba seeds, believing they assisted during childbirth. Hunters and raiders ate jojoba on the trail to keep hunger at bay.

The Seri, who utilize nearly every edible plant in their domain, do not regard the beans as real food and in the past ate it only in emergencies.[2]

Contemporary uses

.JPG.webp)

Jojoba is grown for the liquid wax, commonly called jojoba oil, in its seeds.[7] This oil is rare in that it is an extremely long (C36–C46) straight-chain wax ester and not a triglyceride, making jojoba and its derivative jojoba esters more similar to whale oil than to traditional vegetable oils. Hydrolyzed Jojoba Esters (HJE's) are created via a saponification reaction which liberates more than 12 natural long chain fatty alcohols making them available for anti-viral purposes. Natural HJE's have been shown to be 50 times stronger in in-vitro testing than synthetic docosanol (C22:0) in combating the Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1). Jojoba oil has also been discussed as a possible biodiesel fuel.[8][9][10] Jojoba cannot be cultivated on a scale to compete with traditional fossil fuels, and its use is relegated to personal care products.[11]

Cultivation

Plantations of jojoba have been established in a number of desert and semi-desert areas, predominantly in Argentina, Australia, Israel, Mexico, Peru and the United States. It is currently the Sonoran Desert's second most economically valuable native plant (overshadowed only by Washingtonia filifera—California fan palms, used as ornamental trees).

Jojoba prefers light, coarsely textured soils. Good drainage and water penetration is necessary. It tolerates salinity and nutrient-poor soils. Soil pH should be between 5 and 8.[12] High temperatures are tolerated by jojoba, but frost can damage or kill plants.[13] Requirements are minimal, so jojoba plants do not need intensive cultivation. Weed problems only occur during the first two years after planting and there is little damage by insects. Supplemental irrigation could maximize production where rainfall is less than 400 mm.[12] There is no need for high fertilisation, but, especially in the first year, nitrogen increases growth.[14] Jojoba is normally harvested by hand because seeds do not all mature in the same time. Yield is around 3.5 t/ha depending on the age of the plantation.[12]

Selective breeding is developing plants that produce more beans with higher wax content, as well as other characteristics that will facilitate harvesting.[2]

Its ability to withstand high salinity (up to 12 dS m−1 at pH 9) and the high value of jojoba products make jojoba an interesting plant for the use of desertification control. It has been used to combat and prevent desertification in the Thar Desert in India.[15]

References

- "Simmondsia chinensis (Link) C.K.Schneid". Plants of the World Online. Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Phillips, Steven J.; Comus, Patricia Wentworth, eds. (2000). A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert. University of California Press. pp. 256–257. ISBN 0-520-21980-5.

- Gentry, Howard Scott (July 1958). "The natural history of Jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis) and its cultural aspects". Economic Botany. 12 (3): 261–295. doi:10.1007/BF02859772. S2CID 20974482.

- "Simmondsia chinensis". Jepson eFlora (TJM2). The Jepson Herbarium.

- Tobe, Hiroshi; Yasuda, Sachiko; Oginuma, Kazuo (December 1992). "Seed coat anatomy, karyomorphology, and relationships of Simmondsia (Simmondsiaceae)". The Botanical Magazine Tokyo. 105 (4): 529–538. doi:10.1007/BF02489427. S2CID 31513316.

- Sturtevant, Drew; Lu, Shaoping; Zhou, Zhi-Wei; Shen, Yin; Wang, Shuo; Song, Jia-Ming; Zhong, Jinshun; Burks, David J.; Yang, Zhi-Quan; Yang, Qing-Yong; Cannon, Ashley E. (March 2020). "The genome of jojoba ( Simmondsia chinensis ): A taxonomically isolated species that directs wax ester accumulation in its seeds". Science Advances. 6 (11): eaay3240. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay3240. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7065883. PMID 32195345.

- "Jojoba" (PDF). IENICA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- Franke, Elsa; Lieberei, Reinhard; Reisdorff, Christoph (24 October 2012). Nutzpflanzen: Nutzbare Gewächse der gemäßigten Breiten, Subtropen und Tropen. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag. p. 399.

- Al-Hamamre, Z. (July 2013). "Jojoba is a Possible Alternative Green Fuel for Jordan". Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy. 8 (3): 217–226. doi:10.1080/15567240903330442. S2CID 154094908.

- Al-Widyan, Mohamad I.; Al-Muhtaseb, Mu’taz A. (August 2010). "Experimental investigation of jojoba as a renewable energy source". Energy Conversion and Management. 51 (8): 1702–1707. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2009.11.043.

- Uwe Wolfmeier, Hans Schmidt, Franz-Leo Heinrichs, Georg Michalczyk, Wolfgang Payer, Wolfram Dietsche, Klaus Boehlke, Gerd Hohner, Josef Wildgruber (2002). "Waxes". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a28_103. ISBN 3527306730.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link).

- Yermanos, D. M. (1979). "Jojoba – a crop whose time has come". California Agriculture.

- Borlaug, N. (1985). Jojoba. New Crop for Arid Lands, New Raw Material for Industry. National Academy Press.

- Nelson, M. (2001). "Nitrogen fertilization effects on jojoba seed production". Industrial Crops and Products. 13 (2): 145–154. doi:10.1016/s0926-6690(00)00061-3.

- Alsharhan, Abdulrahman S.; Fowler, Abdulrahman; Goudie, Andrew S.; Abdellatif, Eissa M.; Wood, Warren W. (2003). Desertification in the third millennium. Lisse: Balkema. pp. 151–172. ISBN 978-0-415-88943-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Simmondsia chinensis. |

- USDA Plants Profile for Simmondsia chinensis (jojoba)

- Calflora Database: Simmondsia chinensis (jojoba)

- Jepson Manual (TJM93) treatment of Simmondsia chinensis

- Selected Families of Angiosperms: Rosidae—an explanation of the scientific name

- Newscientist.com: Jojoba oil as biodiesel

- Hort.purdue.edu: Alternative Field Crops Manual

- "Glossary". International Jojoba Export Council. Archived from the original on 2006-07-20.

- Howser, Huell (January 14, 2009). "Jojoba – California's Gold (11014)". California's Gold. Chapman University Huell Howser Archive.

- Uses and Benefits of Jojoba Oils