Jonah ibn Janah

Jonah ibn Janah or ibn Janach,[1] born Abu al-Walīd Marwān ibn Janāḥ ( Arabic: أبو الوليد مروان بن جناح, Hebrew: ר׳ יוֺנָה אִבְּן גַּ֗נָאח,)[2] (c. 990 – c. 1055), was a Jewish rabbi, physician and Hebrew grammarian active in Al-Andalus, or Islamic Spain. Born in Córdoba, ibn Janah was mentored there by Isaac ibn Gikatilla and Isaac ibn Mar Saul, before he moved around 1012, due to the sacking of the city. He then settled in Zaragoza, where he wrote Kitab al-Mustalhaq, which expanded on the research of Judah ben David Hayyuj and led to a series of controversial exchanges with Samuel ibn Naghrillah that remained unresolved during their lifetimes.

Jonah ibn Janah | |

|---|---|

| Personal | |

| Born | between 985 and 990 Córdoba, Caliphate of Córdoba (modern-day Spain) |

| Died | 1055 Zaragoza, Taifa of Zaragoza (modern-day Spain) |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Occupation | Physician |

His magnum opus, Kitab al-Anqih, contained both the first complete grammar for Hebrew and a dictionary of Classical Hebrew, and is considered "the most influential Hebrew grammar for centuries"[3] and a foundational text in Hebrew scholarship. Ibn Janah is considered a very influential scholar in the field of Hebrew grammar; his works and theories were popular and cited by Hebrew scholars in Europe and the Middle East.

Name

The name in which he is known in Hebrew, Jonah ("dove", also spelled Yonah) was based on his Arabic patronymic ibn Janah ("the winged", also spelled ibn Janach).[4][5] His Arabic personal name was Marwan, with the kunyah Abu al-Walid. Latin sources, including Avraham ibn Ezra[6] referred to him as "Rabbi Marinus", a Latinization of his Arabic name Marwan.[4]

Early life

There is little information on his family or early life, mostly known from biographical details found in his writings.[4] He was born in Córdoba, in modern-day Spain and then-capital of the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba between 985 and 990.[4] He studied in the nearby Lucena; his teachers there included Isaac ibn Gikatilla and Isaac ibn Mar Saul.[1][4] His education included the languages of Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic, the exegesis of the Bible and the Quran, as well as rabbinic literature.[4] Ibn Mar Saul was a master of poetry and ibn Janah attempted to write some Hebrew poetry himself, but was not very successful at it.[7][4] Ibn Gikatilla was an expert in both Hebrew and Arabic grammar, and under his tutelage ibn Janah became fluent in Arabic, familiar with Arabic literature and "acquired an easy and graceful" Arabic writing style.[7] Arabic became his language of choice for most of his writings.[2][8] Ibn Janah also mentioned Judah ben David Hayyuj as one of his major influences, but he was unlikely to have met him, because Hayyuj was active in Córdoba and died before ibn Janah returned there.[7]

Around 1012, he returned to Córdoba, where he studied and practiced medicine.[2] By this time, Al-Andalus or the Islamic Iberia was in a period of instability and civil war, known as the Fitna of al-Andalus.[4] Córdoba was besieged and sacked by Berber rebels, who committed atrocities on its citizens, including the Jews.[4][9] The caliphate of Córdoba soon disintegrated into small states known as the taifas.[9] Ibn Janah and many other Jews were forced to leave the capital.[7] He moved to the Upper March region of Al-Andalus,[4] and – after a period of wandering there – settled in Zaragoza.[7] He had at least one son.[4]

Career in Zaragoza

He remained in Zaragoza until the end of his life, where he practiced medicine and wrote books.[4][2] He wrote at least one medical book, Kitab al-Takhlis (Arabic for "Book of the Extract"), on formulae and measures of medical remedies, which for decades was thought to be lost,[4] but recently discovered.[10] Today, the only extant manuscript of this work is preserved in the Süleymaniye Library in Istanbul, Turkey (MS Aya Sofia 3603).

Ibn Janah became known as a successful physician, often called by the epithet "the physician", and was mentioned by the 13th-century Syrian physician Ibn Abi Usaibia in his collection of biographies, Lives of the Physicians.[7][4]

Aside from his work in medicine, he also worked on the field of Hebrew grammar and philology, joining other scholars in Zaragoza including Solomon ibn Gabirol.[5]

Kitab al-Mustalhaq

Ibn Janah was deeply influenced by the works of Judah ben David Hayyuj.[2] Earlier Hebrew grammarians, such as Menahem ben Saruq and the Saadia Gaon, had believed that Hebrew words could have letter roots of any length.[2] Hayyuj argued that this was not the case, and Hebrew roots are consistently triliteral.[2] In his work, Kitab al-Mustalhaq ("Book of Criticism", variously translated as the "Book of Annexation"),[11] or what is also known as Sefer HaHasagh in Hebrew, Ibn Janah strongly supported Hayyuj's work, but proposed some improvements.[2] Among others, he added 54 roots to Hayyuj's 467, filled some gaps and clarified some ambiguities in his theories.[4] A follow-up of this work was written by Ibn Janah, entitled Kitāb al-Taswi'a ("Book of Reprobation"), which he composed as a response to critics of his previous work.[12]

Dispute with Hayyuj's supporters

In Kitab al-Mustalbag, ibn Janah praised Hayyuj's works and acknowledged them as the source for most of his knowledge on Hebrew grammar.[6] He intended for this work to be uncontroversial, and to be an extension to the works of Hayyuj, whom he deeply admired.[5][4] However, the work caused offense among Hayyuj's supporters.[4] They considered Hayyuj the greatest authority of all times, worthy of taqlid or unquestioning conformity.[4] They were offended when ibn Janah, a relatively junior scholar at the time, leveled a criticism on their master and found his works incomplete.[4] One of the disciples of Hayyuj was Samuel ibn Naghrillah, the vizier of the Taifa of Granada, a Muslim state which emerged in the city after the fall of Córdoba.[4] Ibn Janah subsequently wrote the brief Risalat al-Tanbih ("Letter of Admonition"), which defended his views, as well as Risalat al-Taqrib wa l-Tashil ("Letter of Approximation and Facilitation"), which sought to clarify Hayyuj's work for beginners.[4]

While visiting his friend, Abu Sulaiman ibn Taraka, he met a stranger from Granada who enumerated various attacks on ibn Janah's views. Ibn Janah wrote Kitab al-Taswi'a ("Book of Reprobation") to counter the arguments.[4][lower-alpha 1] Ibn Naghrilla then wrote Rasail al-rifaq ("Letters from Friends"), attacking ibn Janah, who then responded by writing Kitab al-Tashwir ("Book of Confusion").[4] Further pamphlets were exchanged between the two, which were later of great benefit to Hebrew grammarians.[13] The pamphlets were in Arabic and were never translated into Hebrew.[6] The debates were unresolved during their lifetimes.[6] Many were lost, but some were reprinted and translated into French.[6]

Kitab al-Anqih

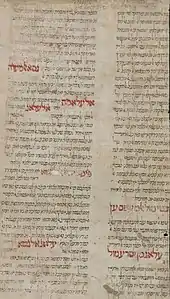

Towards the end of his life, ibn Janah wrote what is considered his magnum opus,[2] the Kitab al-Anqih ("Book of Minute Research"), known in Hebrew as Sefer HaDikduk.[4][13] The book is divided into two sections: Kitab al-Luma ("Book of Many-Colored Flower-Beds"[2]), or Sefer HaRikmah, which covered Hebrew grammar, and Kitab al-Usul ("Book of Roots"[4]), or Sefer HaShorashim, a dictionary of Classical Hebrew words arranged by root.[2]

Kitab al-Luma

Kitab al-Luma (the Book of Variegated Flower-beds) was the first complete Hebrew grammar ever produced.[2] During his time, works of Arabic grammar and Quranic exegesis had a large influence among Hebrew grammarians.[4] In this work, Ibn Janah drew from the Arabic grammatical works of Sibawayh, Al-Mubarrad and others, both referencing them and directly copying from them.[14] The book consisted of 54 chapters, inspired by how Arabic grammars were organized.[15] By using similarities between the two Semitic languages, he adapted existing rules and theories of the Arabic language and used them for Hebrew.[16] These introductions allowed the Bible to be analyzed by criteria similar to those used by Quranic scholars of the time.[4]

Ibn Janah also introduced the concept of lexical substitution in interpreting Classical Hebrew.[17] This concept, in which the meaning of a word in the Bible was substituted by a closely associated word, proved to be controversial.[18] Twelfth-century biblical commentator Abraham ibn Ezra strongly opposed it and called it "madness" close to heresy.[18]

Kitab al-Usul

Kitab al-Usul (The Book of Roots), the dictionary, was arranged into 22 chapters—one for each letter of the Hebrew alphabet.[19] The dictionary included more than 2,000 roots,[16] nearly all of them triliteral.[19] Less than five percent of the roots have more than three letters, and they were added as appendix in each chapter.[16] Definitions for the words were derived from the Talmud, Tanakh or other classical Jewish works, as well as similar Arabic and Aramaic words.[19][16] This approach was controversial and new in Hebrew scholarship.[19] Ibn Janah defended his method by pointing to precedents in the Talmud as well as previous works by Jewish writers in Babylonia and North Africa, which all used examples from other languages to define Hebrew words.[20]

Legacy

Ibn Janah died in approximately 1055,[2] his works quickly became popular among Hebrew scholars in Spain.[20] They were initially inaccessible in other parts of Europe, which did not read Arabic.[20] However, in late twelfth century, Spanish-Jewish scholars in Italy and southern France spread Ibn Janah's work there and to the rest of Europe.[20] Ibn Janah's main work, Kitab al-Anqih, was translated into Hebrew by Judah ben Saul ibn Tibbon in 1214.[21] This translation as well as others spread ibn Janah's methods and fame outside the Arabic-speaking Jews.[16] He was subsequently cited by Hebrew scholars and exegetes in the Iberian peninsula, the Middle East and southern France.[16]

In 1875 Kitab al-Usul was published in English as "The Book of Hebrew Roots", and a second printing with some corrections occurred in 1968. It was republished in Hebrew in 1876.[20]

His work, research and methodology are considered deeply important. The Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World (EJIW) describes him as "one of the best-known, most influential, closely followed, and highly praised scholars" of Hebrew. Professor of Judaic Studies Michael L. Satlow writes that Kitab al-Anqih is "fundamental to the study of Hebrew grammar";[22] Sephardic Studies Professor Zion Zohar calls it "the most influential Hebrew grammar for centuries", and an example of where "medieval Judeo-Arabic literary culture reached its apogee".[3] Writer David Tene "rhapsodizes" on Kitab al-Luna, calling it "the first complete description of Biblical Hebrew, and no similar work - comparable in scope, depth and precision - was written until modern times...[it was] the high point of linguistic thought in all [medieval grammatical] history".[23] The EJIW described Kitab al-Usul as "the basis of all other medieval Hebrew dictionaries".[16] The Jewish Encyclopedia, however, notes "serious gaps" in Kitab al-Tankih, because it does not discuss vowels and accents, and because it omits explaining Hayyuj's works on which it is based on.[24] The Encyclopædia Britannica calls him "perhaps the most important medieval Hebrew grammarian and lexicographer" and says that his works "clarif[ied] the meaning of many words" and contained the "origin of various corrections by modern textual critics".[8]

References

Notes

- According to Martínez-Delgado 2010, p. 501, the stranger was an adversary who attacked his view, while Scherman 1982, p. 64 says that the stranger merely relayed what he remembered from ibn Naghrillah's plan to attack him.

Citations

- Scherman 1982, p. 63

- Brisman 2000, p. 12

- Zohar 2005, p. 46

- Martínez-Delgado 2010, p. 501.

- Scherman 1982, p. 63.

- Scherman 1982, p. 64.

- Toy & Bacher 1906, p. 534.

- Encyclopædia Britannica 1998.

- Scherman 1982, p. 22.

- Fenton (2016), pp. 107–143

- Gallego (2000), p. 90

- Gallego (2000), pp. 90–95

- Scherman 1982, p. 64

- Becker 1996, p. 277.

- Martínez-Delgado 2010, pp. 501–502.

- Martínez-Delgado 2010, p. 502.

- Cohen 2003, pp. 79–80.

- Cohen 2003, p. 80.

- Brisman 2000, p. 12.

- Brisman 2000, p. 13.

- Scherman 1982, p. 65.

- Satlow 2006, p. 213

- Waltke & O'Connor 1990, p. 35

- Toy & Bacher 1906, p. 535.

Bibliography

- Becker, Dan (1996). "Linguistic Rules and Definitions in Ibn Janāḥ's "Kitāb Al-Lumaʿ (Sefer Ha-Riqmah)" Copied from the Arab Grammarians". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 86 (3): 275–298. JSTOR 1454908.

- Brisman, Shimeon (2000). A History and Guide to Judaic Dictionaries and Concordances, Part 1. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press. ISBN 0-88125-658-7.

- Cohen, Mordechai Z. (2003). Three approaches to biblical metaphor: from Abraham Ibn Ezra and Maimonides to David Kimhi (Revised ed.). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9004129715.

- Fenton, Paul B. (2016). "Jonah Ibn Ǧanāḥ's Medical Dictionary, the Kitāb al-Talḫīṣ: Lost and Found". Aleph. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. 16 (1): 107–143. JSTOR 10.2979/aleph.16.1.107.

- Gallego, María A. (2000). "The "Kitāb al-Taswi'a" or "Book of Reprobation" by Jonah ibn Janāḥ. A Revision of J. and H. Derenbourg's Edition". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. London: Cambridge University Press. 63 (1): 90–95. JSTOR 1559590.

- Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (1998). "Ibn Janāḥ". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 2018-03-05.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Martínez-Delgado, José (2010). "Ibn Janāḥ, Jonah (Abū ʾl-Walīd Marwān)". In Norman A. Stillman; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Two:D–I. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

- Satlow, Michael L. (2006). Creating Judaism history, tradition, practice ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-50911-1.

- Scherman, Nosson (1982). The Rishonim (1. ed.). Brooklyn, N.Y.: Mesorah Publ. u.a. ISBN 0-89906-452-3.

- Toy, Crawford Howell; Bacher, Wilhelm (1906). "Ibn Janah, Abu al-Walid Merwan". Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Co.

- Waltke, Bruce K.; O'Connor, M. (1990). An introduction to biblical Hebrew syntax ([Nachdr. ed.). Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-31-5.

- Zohar, Zion, ed. (2005). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry: from the Golden Age of Spain to the Modern Age. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-9705-9.