Kildare Poems

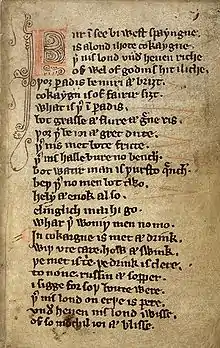

The Kildare Poems or Kildare Lyrics[1] (British Library Harley MS 913) are a group of sixteen poems written in an Irish dialect of Middle English and dated to the mid-14th century. Together with a second, shorter set of poems in the so-called Loscombe Manuscript, they constitute the first and most important linguistic document of the early development of Irish English in the centuries after the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland.[2] The sixteen poems contain both religious and satirical contents. They are preserved in a single manuscript (British Library, Harley 913), where they are scattered between a number of Latin and Old French texts. The conventional modern designation "Kildare poems" refers both to the town of Kildare in Ireland, which has been proposed as their likely place of origin, and to the name of the author of at least one of the poems, who calls himself "Michael (of) Kildare" (Frere Michel Kyldare). The poems have been edited by W. Heuser (1904)[3] and A. Lucas (1995).[4]

History

The Kildare Poems are found in a manuscript that was produced around 1330.[5] It is a small parchment book, measuring only 140 mm by 95 mm, and may have been produced as "a travelling preacher’s 'pocket-book'"[6] The authors or compilers were probably Franciscan friars. Scholars have debated whether the poems' likely place of origin is Kildare in eastern Ireland or Waterford in the south.[7][8] The case for Kildare is based mostly on the reference to the authorship of "Michael of Kildare", and a reference to one "Piers of Birmingham", who is known to have lived in Kildare and who was buried in the Franciscan church in Kildare. The case for Waterford is based, among other things, on a reference to "yung men of Waterford" in one (now lost) part of the manuscript, as well as on certain dialectal features.[2][5] It has also been surmised that a core of the work was produced in Kildare and then copied and expanded with further material in Waterford.[6]

The manuscript was in the possession of George Wyse (Mayor of Waterford in 1571) during the 16th century. In 1608, the manuscript was noted by the antiquarian Sir James Ware, who described it as "a smale olde booke in parchment called the booke of Rose or of Waterford". Ware made several excerpts from the book, including the "Yung men of Waterford" poem that is no longer found in Harley 913 today. Ware's manuscript copy has been preserved as Ms. Landsdowne 418 in the British Library.[6][9] Later, the original book came into the possession of Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, whose library was acquired by the British Museum in 1754.

A first modern printed edition of the text was published by Thomas Wright in Reliquiae Antiquae I in 1841. A standard philological edition of the text is that by Wilhelm Heuser (1904);[3] a more recent edition was offered by Angela Lucas in 1995.[4]

Contents

The religious and satirical contents of the Kildare poems are thought to display ideas characteristic of Franciscan concerns, including a concern for the poor and a dislike of older, established monastic orders.[5] The Kildare poems comprise the following items:

- The Land of Cokaygne: a satirical piece about a corrupt community of monks, who lead a life of fantastic luxury and dissipation in the mythical land of Cockaigne. This satire may be directed against the Cistercian abbey at Inislounaght, near Waterford.[5]

- Five hateful things: a short, seven-line poem expressing a gnomic saying about human vices

- Satire ("Hail, Seint Michel"): a satirical piece about human vices, in twenty short stanzas, each in the form of an incantation to a different saint

- Song of Michael of Kildare: a religious poem, considered the most ambitious literary work among this group of poems,[3] and the only one that names its author ("Frere Michel Kyldare", who also describes himself as a "frere menour", i.e. a minorite).

- Sarmun ("sermon"), Fifteen Signs before Judgment, Fall and Passion, Ten Commandments: four religious verse sermons, in rhymed quatrains

- Christ on the Cross: a religious poem in irregular rhymed long lines

- Lollai, Lollai, litil child: a religious poem in the form of a lullaby song directed to a child

- Song of the Times: a satirical poem criticizing political and social disorder, containing a moral animal fable.

- Seven Sins: a religious poem in six-line stanzas

- Piers of Bermingham: an obituary of an English knight, Sir Piers of Birmingham (of Tethmoy, the region around Edenderry)[10]), who is praised for his military exploits against the Irish and whose death is dated to 13 April 1308.[11]

- Elde, a poem about the problems of old age

- Repentance of Love, a brief poem of three quatrains expressing a lover's complaint

- Nego, a moral poem about denial, symbolized by the Latin word negō ('I deny/reject/refuse')

- Erth a moral poem about earth, in two parallel versions in English and Latin

Linguistic features

The Kildare Poems show many linguistic features common to the Middle English dialects of the west and south-west of England, from which most English-speaking settlers in medieval Ireland had come, but they also display a number of unique features that point towards an independent development of English dialects in Ireland, either because of levelling between different source dialects of English, or because of the influence of Irish. Among the conspicuous features are:[2]

- Occasional replacement of th (þ) with t (e.g. growit for growiþ). This may reflect fortition of /θ/ to a dental stop, as found in some later forms of Irish English.

- Voicing of initial /f/ to /v/ (as in southern Middle English: uadir for father, uoxe for fox), while older /v/ is rendered as <w> (representing [w] or [β], wysage for visage)

- Loss of nasals before coronal stops: fowden for founden, powde for pound

- h-dropping in words like is for his, abbiþ for habbiþ

- raising of short /e/ to /i/ in unstressed final syllables

- metathesis in words like fryst < first, gradener < gardener, possibly related to similar phenomena in Irish

- epenthesis of <e> in consonant clusters in some words like Auerill < April, uerisse < freshe, also possibly related to similar phenomena in Irish and in later forms of Irish English

Text sample

The following is a passage from the Land of Cokaygne, describing the immoral conduct of monks and nuns:

| Middle English text[4] | Modern English translation |

|---|---|

An-other abbei is ther-bi, |

There is another abbey nearby, |

References

- http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=18695

- Hickey, Raymond (2007). Irish English: History and Present-Day Forms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 54–66.

- Heuser, Wilhelm (1904). Die Kildare-Gedichte: die ältesten mittelenglischen Denkmäler in anglo-irischer Überlieferung. Bonn: Hanstein.

- Lucas, Angela (1995). Anglo-Irish Poems of the Middle Ages. Dublin: Columba.

- Dolan, Terence. "Kildare poems". The Oxford Companion to Irish History. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- Lucas, Angela. "British Library Manuscript Harley 913". Medieval Ireland: an Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- Benskin, Michael (1989). "The style and authorship of the Kildare Poems". In Mackenzie, J. L.; Todd, R. (eds.). In Other Words: Transcultural Studies in Philology, Translation and Lexicology. Dordrecht: Foris. pp. 57–75.

- McIntosh, Angus; Samuels, Michael (1968). "Prolegomena to a study of medieval Anglo-Irish". Medium Ævum. 37: 1–11.

- Heuser 1904, p. 11.

- http://oracleireland.com/Ireland/chronology/berminghan.htm

- Fitzmaurice, E.B.; Little; A.G. (1920). Materials for the History of the Franciscan Province of Ireland, AD 1230–1450. Manchester: University Press. pp. 88–89.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT): Online text of the Kildare Poems, based on the edition of Lucas (1995). Cork: University College.

- Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse: Online text of the Kildare Poems, based on the edition of Heuser (1904). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

- Wessex Parallel Web Texts: The Land of Cockaigne, with modern English translation and image of the manuscript