Lake Baikal

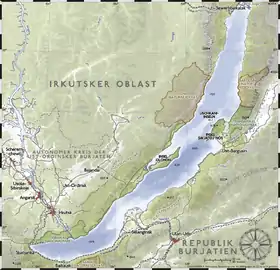

Lake Baikal (/baɪˈkɑːl, -ˈkæl/;[3] Russian: озеро Байкал, tr. Ozero Baykal, IPA: [ˈozʲɪrə bɐjˈkaɫ]; Buryat: Байгал нуур, Baigal nuur)[4] is a rift lake located in southern Siberia, Russia, between Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the Buryat Republic to the southeast.

| Lake Baikal | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

Lake Baikal | |

| |

| Location | Siberia, Russia |

| Coordinates | 53°30′N 108°0′E |

| Lake type | Ancient lake, Continental rift lake |

| Primary inflows | Selenga, Barguzin, Upper Angara |

| Primary outflows | Angara |

| Catchment area | 560,000 km2 (216,000 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Mongolia and Russia |

| Max. length | 636 km (395 mi) |

| Max. width | 79 km (49 mi) |

| Surface area | 31,722 km2 (12,248 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth | 744.4 m (2,442 ft)[1] |

| Max. depth | 1,642 m (5,387 ft)[1] |

| Water volume | 23,615.39 km3 (5,670 cu mi)[1] |

| Residence time | 330 years[2] |

| Shore length1 | 2,100 km (1,300 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 455.5 m (1,494 ft) |

| Frozen | January–May |

| Islands | 27 (Olkhon Island) |

| Settlements | Severobaykalsk, Slyudyanka, Baykalsk, Ust-Barguzin |

| Criteria | Natural: vii, viii, ix, x |

| Reference | 754 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th session) |

| Area | 8,800,000 ha |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Lake Baikal is the largest freshwater lake by volume in the world, containing 22 to 23% of the world's fresh surface water.[5][6] With 23,615.39 km3 (5,670 cu mi) of fresh water,[1] it contains more water than all of the North American Great Lakes combined.[7] With a maximum depth of 1,642 m (5,387 ft),[1] Baikal is the world's deepest lake.[8] It is among the world's clearest[9] lakes and is the world's oldest lake,[10] at 25–30 million years.[11][12] It is the seventh-largest lake in the world by surface area.

Lake Baikal formed as an ancient rift valley and has a long, crescent shape, with a surface area of 31,722 km2 (12,248 sq mi), slightly larger than Belgium. Baikal is home to thousands of species of plants and animals, many of them endemic to the region. It is also home to Buryat tribes, who raise goats, camels, cattle, sheep, and horses[13] on the eastern side of the lake,[14] where the mean temperature varies from a winter minimum of −19 °C (−2 °F) to a summer maximum of 14 °C (57 °F).[15]

The region to the east of Lake Baikal is referred to as Transbaikalia or as the Transbaikal, and the loosely defined region around the lake itself is sometimes known as Baikalia. UNESCO declared Lake Baikal a World Heritage Site in 1996.[16]

Geography and hydrography

Lake Baikal is in a rift valley, created by the Baikal Rift Zone, where the Earth's crust is slowly pulling apart.[17] At 636 km (395 mi) long and 79 km (49 mi) wide, Lake Baikal has the largest surface area of any freshwater lake in Asia, at 31,722 km2 (12,248 sq mi), and is the deepest lake in the world at 1,642 m (5,387 ft). The bottom of the lake is 1,186.5 m (3,893 ft) below sea level, but below this lies some 7 km (4.3 mi) of sediment, placing the rift floor some 8–11 km (5.0–6.8 mi) below the surface, the deepest continental rift on Earth.[17] In geological terms, the rift is young and active – it widens about 2 cm (0.8 in) per year. The fault zone is also seismically active; hot springs occur in the area and notable earthquakes happen every few years. The lake is divided into three basins: North, Central, and South, with depths about 900 m (3,000 ft), 1,600 m (5,200 ft), and 1,400 m (4,600 ft), respectively. Fault-controlled accommodation zones rising to depths about 300 m (980 ft) separate the basins. The North and Central basins are separated by Academician Ridge, while the area around the Selenga Delta and the Buguldeika Saddle separates the Central and South basins. The lake drains into the Angara, a tributary of the Yenisey. Notable landforms include Cape Ryty on Baikal's northwest coast.

Baikal's age is estimated at 25–30 million years, making it the most ancient lake in geological history.[11][12] It is unique among large, high-latitude lakes, as its sediments have not been scoured by overriding continental ice sheets. Russian, U.S., and Japanese cooperative studies of deep-drilling core sediments in the 1990s provide a detailed record of climatic variation over the past 6.7 million years.[18][19] Longer and deeper sediment cores are expected in the near future. Lake Baikal is the only confined freshwater lake in which direct and indirect evidence of gas hydrates exists.[20][21][22]

The lake is surrounded by mountains; the Baikal Mountains on the north shore, the Barguzin Range on the northeastern shore, and the taiga are protected as a national park. It contains 27 islands; the largest, Olkhon, is 72 km (45 mi) long and is the third-largest lake-bound island in the world. The lake is fed by as many as 330 inflowing rivers.[23] The main ones draining directly into Baikal are the Selenga, the Barguzin, the Upper Angara, the Turka, the Sarma, and the Snezhnaya. It is drained through a single outlet, the Angara.

Regular winds exist in Baikal's rift valley.[24] The Kultuk blows southwest and the Verkhovik blows north or northeast. Together, these winds cause waves as high as 6 meters. In addition, transverse winds blow locally and over shorter distances. The Sarma (named after the Sarma River) blows northwest in the autumn through the Sarma valley and the strait of Olkhon Island. The Barguzin (named after the Barguzin river) blows northeast in the spring.

Cliffs on Olkhon Island

Cliffs on Olkhon Island A sandy beach in the Kabansky District

A sandy beach in the Kabansky District Mountains on the Svyatoy Nos Peninsula, Zabaykalsky National Park

Mountains on the Svyatoy Nos Peninsula, Zabaykalsky National Park The river Turka at its mouth before joining Lake Baikal

The river Turka at its mouth before joining Lake Baikal

Water characteristics

Baikal is one of the clearest lakes in the world.[9] During the winter, the water transparency in open sections can be as much as 30–40 m (100–130 ft), but during the summer it is typically 5–8 m (15–25 ft).[25] Baikal is rich in oxygen, even in deep sections,[25] which separates it from distinctly stratified bodies of water such as Lake Tanganyika and the Black Sea.[26][27]

In Lake Baikal, the water temperature varies significantly depending on location, depth, and time of the year. During the winter and spring, the surface freezes for about 4–5 months; from early January to early May–June (latest in the north), the lake surface is covered in ice.[28] On average, the ice reaches a thickness of 0.5 to 1.4 m (1.6–4.6 ft),[29] but in some places with hummocks, it can be more than 2 m (6.6 ft).[28] During this period, the temperature slowly increases with depth in the lake, being coldest near the ice-covered surface at around freezing, and reaching about 3.5–3.8 °C (38.3–38.8 °F) at a depth of 200–250 m (660–820 ft).[30] After the surface ice breaks up, the surface water is slowly warmed up by the sun, and in May–June, the upper 300 m (980 ft) or so becomes homothermic (same temperature throughout) at around 4 °C (39 °F) because of water mixing.[25][30] The sun continues to heat up the surface layer, and at the peak in August can reach up to about 16 °C (61 °F) in the main sections[30] and 20–24 °C (68–75 °F) in shallow bays in the southern half of the lake.[25][31] During this time, the pattern is inverted compared to the winter and spring, as the water temperature falls with increasing depth. As the autumn begins, the surface temperature falls again and a second homothermic period at around 4 °C (39 °F) of the upper circa 300 m (980 ft) occurs in October–November.[25][30] In the deepest parts of the lake, from about 300 m (980 ft), the temperature is stable at 3.1–3.4 °C (37.6–38.1 °F) with only minor annual variations.[30]

The average surface temperature has risen by almost 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) in the last 50 years, resulting in a shorter period where the lake is covered by ice.[12] At some locations, hydrothermal vents with water that is about 50 °C (122 °F) have been found. These are mostly in deep water but locally have also been found in relatively shallow water. They have little effect on the lake's temperature because of its huge volume.[30]

Stormy weather on the lake is common, especially during the summer and fall, and can result in waves as high as 4.5 m (15 ft).[25]

Lake Baikal as seen from the OrbView-2 satellite

Lake Baikal as seen from the OrbView-2 satellite Spring ice melt underway on Lake Baikal, on 4 May: Notice the ice-covered north, while much of the south is already ice-free.

Spring ice melt underway on Lake Baikal, on 4 May: Notice the ice-covered north, while much of the south is already ice-free. Circle of thin ice, diameter of 4.4 km (2.7 mi) at the lake's southern tip, probably caused by convection

Circle of thin ice, diameter of 4.4 km (2.7 mi) at the lake's southern tip, probably caused by convection Delta of the Selenga River, Baikal's main tributary

Delta of the Selenga River, Baikal's main tributary

Fauna and flora

Lake Baikal is rich in biodiversity. It hosts more than 1,000 species of plants and 2,500 species of animals based on current knowledge, but the actual figures for both groups are believed to be significantly higher.[25][32] More than 80% of the animals are endemic.[32]

Flora

The watershed of Lake Baikal has numerous floral species represented. The marsh thistle (Cirsium palustre) is found here at the eastern limit of its geographic range.[33]

Submerged macrophytic vascular plants are mostly absent, except in some shallow bays along the shores of Lake Baikal.[34] More than 85 species of submerged macrophytes have been recorded, including genera such as Ceratophyllum, Myriophyllum, Potamogeton, and Sparganium.[31] The invasive species Elodea canadensis was introduced to the lake in the 1950s.[34] Instead of vascular plants, aquatic flora is often dominated by several green algae species, notably Draparnaldioides, Tetraspora, and Ulothrix in water shallower than 20 m (65 ft); although Aegagrophila, Cladophora, and Draparnaldioides may occur deeper than 30 m (100 ft).[34] Except for Ulothrix, there are endemic Baikal species in all these green algae genera.[34] More than 400 diatom species, both benthic and planktonic, are found in the lake, and about half of these are endemic to Baikal; however, significant taxonomic uncertainties remain for this group.[34]

Mammals

The Baikal seal or nerpa (Pusa sibirica) is found throughout Lake Baikal.[35] It is one of only three entirely freshwater seal populations in the world, the other two being subspecies of ringed seals.

A wide range of land mammals can be found in the habitats around the lake, such as Eurasian brown bear, Eurasian wolf, red fox, sable, stoat, elk, Siberian red deer, reindeer, Siberian roe deer, Siberian musk deer, wild boar, red squirrel, Siberian chipmunk, marmot, lemming, and Alpine hare.[36] Until the Early Middle Ages, the wisent (European bison) was present near the lake, which was the easternmost part of its range.[37]

Birds

There are 236 species of birds that inhabit Lake Baikal, 29 of which are waterfowl.[38] Although named after the lake, both the Baikal teal and Baikal bush warbler are widespread in eastern Asia.[39][40]

Fish

Fewer than 65 native fish species occur in the lake basin, but more than half of these are endemic.[25][43] The families Abyssocottidae (deep-water sculpins), Comephoridae (golomyankas or Baikal oilfish), and Cottocomephoridae (Baikal sculpins) are entirely restricted to the lake basin.[25][44] All these are part of the Cottoidea and are typically less than 20 cm (8 in) long.[34] Of particular note are the two species of golomyanka (Comephorus baicalensis and C. dybowskii). These long-finned, translucent fish typically live in open water at depths of 100–500 m (330–1,640 ft), but occur both shallower and much deeper. Together with certain abyssocottid sculpins, they are the deepest living freshwater fish in the world, occurring to near the bottom of Lake Baikal.[45] The golomyankas are the primary prey of the Baikal seal and represent the largest fish biomass in the lake.[46] Beyond members of Cottoidea, there are few endemic fish species in the lake basin.[25][43]

The most important local species for fisheries is the omul (Coregonus migratorius), an endemic whitefish.[25] It is caught, smoked, and then sold widely in markets around the lake. Also, a second endemic whitefish inhabits the lake, C. baicalensis.[47] The Baikal black grayling (Thymallus baicalensis), Baikal white grayling (T. brevipinnis), and Baikal sturgeon (Acipenser baerii baicalensis) are other important species with commercial value. They are also endemic to the Lake Baikal basin.[41][42][48][49]

Invertebrates

The lake hosts a rich endemic fauna of invertebrates. The copepod Epischura baikalensis is endemic to Lake Baikal and the dominating zooplankton species there, making up 80 to 90% of total biomass.[50] It is estimated that the epischurans filter as much as a thousand cubic kilometers of water a year, or the lake's entire volume every twenty-three years.[51]

Among the most diverse invertebrate groups are the amphipod and ostracod crustaceans, freshwater snails, annelid worms and turbellarian worms:

Amphipod and ostracod crustaceans

More than 350 species and subspecies of amphipods are endemic to the lake.[32] They are exceptionally diverse in ecology and appearance, ranging from the pelagic Macrohectopus to the relatively large deep-water Abyssogammarus and Garjajewia, the tiny herbivorous Micruropus, and the parasitic Pachyschesis (parasitic on other amphipods).[52] The "gigantism" of some Baikal amphipods, which has been compared to that seen in Antarctic amphipods, has been linked to the high level of dissolved oxygen in the lake.[53] Among the "giants" are several species of spiny Acanthogammarus and Brachyuropus (Acanthogammaridae) found at both shallow and deep depths.[54] These conspicuous and common amphipods are essentially carnivores (will also take detritus), and can reach a body length up to 7 cm (2.8 in).[52][54]

Similar to another ancient lake, Tanganyika, Baikal is a center for ostracod diversity. About 90% of the Lake Baikal ostracods are endemic,[55] meaning that there are c. 200 endemic species.[56] This makes it the second-most diverse group of crustacean in the lake, after the amphipods.[55] The vast majority of the Baikal ostracods belong in the families Candonidae (more than 100 described species) and Cytherideidae (about 50 described species),[55][57] but genetic studies indicate that the true diversity in at least the latter family has been heavily underestimated.[58] The morphology of the Baikal ostracods is highly diverse.[55]

Snails and bivalves

As of 2006, almost 150 freshwater snails are known from Lake Baikal, including 117 endemic species from the subfamilies Baicaliinae (part of the Amnicolidae) and Benedictiinae (part of the Lithoglyphidae), and the families Planorbidae and Valvatidae.[59] All endemics have been recorded between 20 and 30 m (66 and 98 ft), but the majority mainly live at shallower depths.[59] About 30 freshwater snail species can be seen deeper than 100 m (330 ft), which represents the approximate limit of the sunlight zone, but only 10 are truly deepwater species.[59] In general, Baikal snails are thin-shelled and small. Two of the most common species are Benedictia baicalensis and Megalovalvata baicalensis.[60] Bivalve diversity is lower with more than 30 species; about half of these, all in the families Euglesidae, Pisidiidae, and Sphaeriidae, are endemic (the only other family in the lake is the Unionidae with a single nonendemic species).[60][61] The endemic bivalves are mainly found in shallows, with few species from deep water.[62]

Aquatic worms

With almost 200 described species, including more than 160 endemics, the center of diversity for aquatic freshwater oligochaetes is Lake Baikal.[63] A smaller number of other freshwater annelids is known: 30 species of leeches (Hirudinea),[64] and 4 polychaetes.[63] Several hundred species of nematodes are known from the lake, but a large percentage of these are undescribed.[63]

More than 140 endemic flatworm (Plathelminthes) species are in Lake Baikal, where they occur on a wide range of bottom types.[65] Most of the flatworms are predatory, and some are relatively brightly marked. They are often abundant in shallow waters, where they are typically less than 2 cm (1 in) long, but in deeper parts of the lake, the largest, Baikaloplana valida, can reach up to 30 cm (1 ft) when outstretched.[34][65]

Sponges

At least 18 species of sponges occur in the lake,[66] including 14 species from the endemic family Lubomirskiidae (the remaining are from the nonendemic family Spongillidae).[67] In the nearshore regions of Baikal, the largest benthic biomass is sponges.[66] Lubomirskia baicalensis, Baikalospongia bacillifera, and B. intermedia are unusually large for freshwater sponges and can reach 1 m (3.3 ft) or more.[66][68] These three are also the most common sponges in the lake.[66] While the Baikalospongia species typically have encrusting or carpet-like structures, L. baikalensis often has branching structures and in areas where common may form underwater "forests".[69] Most sponges in the lake are typically green when alive because of symbiotic chlorophytes (zoochlorella), but can also be brownish or yellowish.[70]

History

The Baikal area, sometimes known as Baikalia, has a long history of human habitation. Near the village of Mal'ta, some 160 km northwest of the lake, remains of a young human male known as MA-1 or "Mal'ta Boy" are indications of local habitation by the Mal'ta–Buret' culture ca. 24,000 BP. An early known tribe in the area was the Kurykans.[71]

Located in the former northern territory of the Xiongnu confederation, Lake Baikal is one site of the Han–Xiongnu War, where the armies of the Han dynasty pursued and defeated the Xiongnu forces from the second century BC to the first century AD. They recorded that the lake was a "huge sea" (hanhai) and designated it the North Sea (Běihǎi) of the semimythical Four Seas.[72] The Kurykans, a Siberian tribe who inhabited the area in the sixth century, gave it a name that translates to "much water". Later on, it was called "natural lake" (Baygal nuur) by the Buryats and "rich lake" (Bay göl) by the Yakuts.[73] Little was known to Europeans about the lake until Russia expanded into the area in the 17th century. The first Russian explorer to reach Lake Baikal was Kurbat Ivanov in 1643.[74]

Russian expansion into the Buryat area around Lake Baikal[75] in 1628–58 was part of the Russian conquest of Siberia. It was done first by following the Angara River upstream from Yeniseysk (founded 1619) and later by moving south from the Lena River. Russians first heard of the Buryats in 1609 at Tomsk. According to folktales related a century after the fact, in 1623, Demid Pyanda, who may have been the first Russian to reach the Lena, crossed from the upper Lena to the Angara and arrived at Yeniseysk.[76]

Vikhor Savin (1624) and Maksim Perfilyev (1626 and 1627–28) explored Tungus country on the lower Angara. To the west, Krasnoyarsk on the upper Yenisei was founded in 1627. A number of ill-documented expeditions explored eastward from Krasnoyarsk. In 1628, Pyotr Beketov first encountered a group of Buryats and collected yasak (tribute) from them at the future site of Bratsk. In 1629, Yakov Khripunov set off from Tomsk to find a rumored silver mine. His men soon began plundering both Russians and natives. They were joined by another band of rioters from Krasnoyarsk, but left the Buryat country when they ran short of food. This made it difficult for other Russians to enter the area. In 1631, Maksim Perfilyev built an ostrog at Bratsk. The pacification was moderately successful, but in 1634, Bratsk was destroyed and its garrison killed. In 1635, Bratsk was restored by a punitive expedition under Radukovskii. In 1638, it was besieged unsuccessfully.

In 1638, Perfilyev crossed from the Angara over the Ilim portage to the Lena River and went downstream as far as Olyokminsk. Returning, he sailed up the Vitim River into the area east of Lake Baikal (1640) where he heard reports of the Amur country. In 1641, Verkholensk was founded on the upper Lena. In 1643, Kurbat Ivanov went further up the Lena and became the first Russian to see Lake Baikal and Olkhon Island. Half his party under Skorokhodov remained on the lake, reached the Upper Angara at its northern tip, and wintered on the Barguzin River on the northeast side.

In 1644, Ivan Pokhabov went up the Angara to Baikal, becoming perhaps the first Russian to use this route, which is difficult because of the rapids. He crossed the lake and explored the lower Selenge River. About 1647, he repeated the trip, obtained guides, and visited a 'Tsetsen Khan' near Ulan Bator. In 1648, Ivan Galkin built an ostrog on the Barguzin River which became a center for eastward expansion. In 1652, Vasily Kolesnikov reported from Barguzin that one could reach the Amur country by following the Selenga, Uda, and Khilok Rivers to the future sites of Chita and Nerchinsk. In 1653, Pyotr Beketov took Kolesnikov's route to Lake Irgen west of Chita, and that winter his man Urasov founded Nerchinsk. Next spring, he tried to occupy Nerchensk, but was forced by his men to join Stephanov on the Amur. Nerchinsk was destroyed by the local Tungus, but restored in 1658.

The Trans-Siberian Railway was built between 1896 and 1902. Construction of the scenic railway around the southwestern end of Lake Baikal required 200 bridges and 33 tunnels. Until its completion, a train ferry transported railcars across the lake from Port Baikal to Mysovaya for a number of years. The lake became the site of the minor engagement between the Czechoslovak legion and the Red Army in 1918. At times during winter freezes, the lake could be crossed on foot, though at risk of frostbite and deadly hypothermia from the cold wind moving unobstructed across flat expanses of ice. In the winter of 1920, the Great Siberian Ice March occurred, when the retreating White Russian Army crossed frozen Lake Baikal. The wind on the exposed lake was so cold, many people died, freezing in place until spring thaw. Beginning in 1956, the impounding of the Irkutsk Dam on the Angara River raised the level of the lake by 1.4 m (4.6 ft).[77]

As the railway was built, a large hydrogeographical expedition headed by F.K. Drizhenko produced the first detailed contour map of the lake bed.[10]

Russian map circa 1700, Baikal (not to scale) is at top

Russian map circa 1700, Baikal (not to scale) is at top Steam locomotive on the Circum-Baikal Railroad

Steam locomotive on the Circum-Baikal Railroad Angara was launched in 1900 and is one of the oldest surviving icebreakers

Angara was launched in 1900 and is one of the oldest surviving icebreakers

Research

Several organizations are carrying out natural research projects on Lake Baikal. Most of them are governmental or associated with governmental organizations. The Baikalian Research Centre is an independent research organization carrying out environmental, educational and research projects at Lake Baikal.[78]

In July 2008, Russia sent two small submersibles, Mir-1 and Mir-2, to descend 1,592 m (5,223 ft) to the bottom of Lake Baikal to conduct geological and biological tests on its unique ecosystem. Although originally reported as being successful, they did not set a world record for the deepest freshwater dive, reaching a depth of only 1,580 m (5,180 ft).[79] That record is currently held by Anatoly Sagalevich, at 1,637 m (5,371 ft) (also in Lake Baikal aboard a Pisces submersible in 1990).[79][80] Russian scientist and federal politician Artur Chilingarov, the leader of the mission, took part in the Mir dives[81] as did Russian leader Vladimir Putin.[82]

Since 1993, neutrino research has been conducted at the Baikal Deep Underwater Neutrino Telescope (BDUNT). The Baikal Neutrino Telescope NT-200 is being deployed in Lake Baikal, 3.6 km (2.2 mi) from shore at a depth of 1.1 km (0.68 mi). It consists of 192 optical modules.[83]

Economy

The lake, nicknamed "the Pearl of Siberia", drew investors from the tourist industry as energy revenues sparked an economic boom.[85] Viktor Grigorov's Grand Baikal in Irkutsk is one of the investors, who planned to build three hotels, creating 570 jobs. In 2007, the Russian government declared the Baikal region a special economic zone. A popular resort in Listvyanka is home to the seven-story Hotel Mayak. At the northern part of the lake, Baikalplan (a German NGO) built together with Russians in 2009 the Frolikha Adventure Coastline Track, a 100 km (62 mi)-long long-distance trail as an example for sustainable development of the region. Baikal was also declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996. Rosatom plans to build a laboratory near Baikal, in conjunction with an international uranium plant and to invest $2.5 billion in the region and create 2,000 jobs in the city of Angarsk.[85]

Lake Baikal is a popular destination among tourists from all over the world. According to the Russian Federal State Statistics Service, in 2013, 79,179 foreign tourists visited Irkutsk and Lake Baikal; in 2014, 146,937 visitors. The most popular places to stay by the lake are Listvyanka village, Olkhon Island, Kotelnikovsky cape, Baykalskiy Priboi, resort Khakusy and Turka village. The popularity of Lake Baikal is growing from year to year, but there is no developed infrastructure in the area. For the quality of service and comfort from the visitor's point of view, Lake Baikal still has a long way to go.

The ice road to Olkhon Island is the only legal ice road on Lake Baikal. The route is prepared by specialists every year and it opens when the ice conditions allow it. In 2015, the ice road to Olkhon was open from 17 February to 23 March. The thickness of the ice on the road is about 60 cm (24 in), maximum capacity allowed – 10 t (9.8 long tons; 11 short tons); it is open to the public from 9 am to 6 pm. The road through the lake is 12 km (7.5 mi) long and it goes from the village Kurkut on the mainland, to Irkutskaya Guba on Olkhon Island.[86]

Ecotourism

Baikal has a number of different tourist activities, depending on the season. Generally, Baikal has two top tourist seasons. The first season is ice season, which starts usually in mid-January and lasts till mid-April.[87] During this season ice depth increases up to 140 centimeters, that allows safe vehicle driving on the ice cover (except heavy vehicles, such as tourist buses, that do not take this risk). This allows access to the figures of ice that are formed at rocky banks of Olkhon Island, including Cape Hoboy, the Three Brothers rock, and caves to the North of Khuzhir. It also provides access to small islands like Ogoy Island and Zamogoy.

The ice itself has a transparency of one meter depth, having different patterns of crevasses, bubbles, and sounds. That is why this season is popular for hiking, ice-walking, ice-skating, and bicycle-riding.[88] An ice route around Olkhon is around 200 km. Some tourists may spot a Baikal seal along the route. Local entrepreneurs offer overnight in Yurt on ice. Also this season attracts fans of ice fishing. This activity is most popular on Buryatia side of Baikal (Ust-Barguzin). Non-fishermen may try fresh Baikal fish in local village markets. (Listvyanka, Ust-Barguzin).

The ice season ends in mid-April. Owing to increasing temperatures ice starts to melt and becomes shallow and fragile, especially in places with strong under-ice flows. Vehicles and people start to fall under ice. This leads to many casualties every year.

The second tourist season is summer, which lets tourists dive deeper into virgin Baikal nature. Hiking trails become open,[89] many of them cross two mountain ranges: Baikal Range on the western side and Barguzin Range on the eastern side of Baikal. The most popular trail starts in Listvyanka and goes along the Baikal coast to Bolshoye Goloustnoye. The total length of the route is 55 km, but the most part of tourists usually take only a part of it – a section of 25 km to Bolshie Koty. It has a lower difficulty level and could be passed by people without special skills and gear.

Small tourist vessels operate in the area, availing bird-watching, animal watching (especially Baikal seal), and fishing. Water in the lake stays extremely cold in most places (does not exceed 10 C most of the year), but in few gulfs like Chivirkuy it can be comfortable for swimming.[90]

Olkhon's most-populated village Khuzhir is an ecotourist destination.[91] Baikal has always been popular in Russia and CIS-countries, but for the last few years Baikal has seen an influx of visitors from China and Europe.[92]

Environmental concerns

Lake Baikal faces a series of detrimental phenomena including the disappearance of the omul fish, the rapid growth of putrid algae and the death of endemic species of sponges across its area.[93] Environmental advocacy for the lake began in the late 1950s.[94]

Baykalsk Pulp and Paper Mill

The Baykalsk Pulp and Paper Mill was constructed in 1966, directly on the shoreline of Lake Baikal. The plant bleached paper using chlorine and discharged waste directly into Lake Baikal. The decision to construct the plant on the Lake Baikal resulted in strong protests from Soviet scientists; according to them, the ultra-pure water of the lake was a significant resource and should have been used for innovative chemical production (for instance, the production of high-quality viscose for the aeronautics and space industries). The Soviet scientists felt that it was irrational to change Lake Baikal's water quality by beginning paper production on the shore. It was their position that it was also necessary to preserve endemic species of local biota, and to maintain the area around Lake Baikal as a recreation zone.[95] However, the objections of the Soviet scientists faced opposition from the industrial lobby and only after decades of protest, the plant was closed in November 2008 due to unprofitability.[96][97] In March 2009, the plant owner announced the paper mill would never reopen.[98] However, on 4 January 2010, production was resumed. Later that year on 13 January 2010, Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin introduced changes in the legislation legalising the operation of the plant; this action brought about a wave of protests from ecologists and local residents.[99] These changes were based on the determination President Putin made through a visual verification of Lake Baikal's condition from a miniature submarine, "I could see with my own eyes – and scientists can confirm – Baikal is in good condition and there is practically no pollution".[100] Despite this, in September 2013, the mill underwent a final bankruptcy, with the last 800 workers slated to lose their jobs by 28 December 2013.[101] On the day the plant was to close, 28 December 2013, the Russian government announced plans to build the Russian Nature Reserve's Expo Center in place of the closed paper mill.[102]

Cancelled East Siberia-Pacific Ocean oil pipeline

Russian oil pipelines state company Transneft[103] was planning to build a trunk pipeline that would have come within 800 m (2,600 ft) of the lake shore in a zone of substantial seismic activity. Environmental activists in Russia,[104] Greenpeace, Baikal pipeline opposition[105] and local citizens[106] were strongly opposed to these plans, due to the possibility of an accidental oil spill that might cause significant damage to the environment. According to the Transneft's president, numerous meetings with citizens near the lake were held in towns along the route, especially in Irkutsk.[107] Transneft agreed to alter its plans when Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered the company to consider an alternative route 40 kilometers (25 mi) to the north to avoid such ecological risks.[108] Transneft has since decided to move the pipeline away from Lake Baikal, so that it will not pass through any federal or republic natural reserves.[109][110] Work began on the pipeline two days after President Putin agreed to changing the route away from Lake Baikal.[111]

Proposed uranium enrichment centre

In 2006, the Russian government announced plans to build the world's first international uranium enrichment center at an existing nuclear facility in Angarsk, a city on the river Angara some 95 km (59 mi) downstream from the lake's shores. Critics and environmentalists argued it would be a disaster for the region and are urging the government to reconsider.[112]

After enrichment, only 10% of the uranium-derived radioactive material would be exported to international customers,[112] leaving 90% near the Lake Baikal region for storage. Uranium tailings contain radioactive and toxic materials, which if improperly stored, are potentially dangerous to humans and can contaminate rivers and lakes.[112]

An enrichment center was constructed in the 2010s.[113]

Chinese-owned bottled water plant

Chinese-owned AquaSib has been purchasing land along the lake and started building a bottling plant and pipeline in the town of Kultuk. The goal was to export 190 million liters of water to China even though the lake had been experiencing historically low water levels. This spurred protests by the local population that the lake would be drained of its water, at which point the local government halted the plans pending analysis.[114]

Other pollution sources

According to The Moscow Times and Vice, an increasing number of an invasive species of algae thrives in the lake from hundreds of tons of liquid waste, including fuel and excrement, regularly disposed into the lake by tourist sites, and up to 25,000 tons of liquid waste are disposed of every year by local ships.[115][116]

Historical traditions

The first European to reach the lake is said to have been Kurbat Ivanov in 1643.[117]

In the past, the Baikal was referred to by many Russians as the "Baikal Sea" (море Байкал, More Baikal), rather than merely "Lake Baikal" (озеро Байкал, Ozero Baikal).[118] This usage is attested already in the Life of Protopope Avvakum (1621–1682),[119] and on the late-17th-century maps by Semyon Remezov.[120] It is also attested in the famous song, now passed into the tradition, that opens with the words Славное море, священный Байкал (Glorious sea, [the] sacred Bajkal). To this day, the strait between the western shore of the Lake and the Olkhon Island is called Maloye More (Малое море), i.e. "the Little Sea".

Lake Baikal is nicknamed "Older sister of Sister Lakes (Lake Khövsgöl and Lake Baikal)".[121]

According to 19th-century traveler T. W. Atkinson, locals in the Lake Baikal Region had the tradition that Christ visited the area:

The people have a tradition in connection with this region which they implicitly believe. They say "that Christ visited this part of Asia and ascended this summit, whence he looked down on all the region around. After blessing the country to the northward, he turned towards the south, and looking across the Baikal, he waved his hand, exclaiming 'Beyond this there is nothing.'" Thus they account for the sterility of Daouria, where it is said "no corn will grow."[122]

Lake Baikal has been celebrated in several Russian folk songs. Two of these songs are well known in Russia and its neighboring countries, such as Japan.

- "Glorious Sea, Sacred Baikal" (Славное мope, священный Байкал) is about a katorga fugitive. The lyrics as documented and edited in the 19th century by Dmitriy P. Davydov (1811–1888).[123] See "Barguzin River" for sample lyrics.

- "The Wanderer" (Бродяга) is about a convict who had escaped from jail and was attempting to return home from Transbaikal.[124] The lyrics were collected and edited in the 20th century by Ivan Kondratyev.

The latter song was a secondary theme song for the Soviet Union's second color film, Ballad of Siberia (1947; Сказание о земле Сибирской).

References

- "A new bathymetric map of Lake Baikal. Morphometric Data. INTAS Project 99-1669. Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium; Consolidated Research Group on Marine Geosciences (CRG-MG), University of Barcelona, Spain; Limnological Institute of the Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Irkutsk, Russian Federation; State Science Research Navigation-Hydrographic Institute of the Ministry of Defense, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation". Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- M.A. Grachev. "On the present state of the ecological system of lake Baikal". Limnological Institute, Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- "Baikal". Collins English Dictionary.

- Dervla Murphy (2007) Silverland: A Winter Journey Beyond the Urals, London, John Murray, p. 173

- Schwarzenbach, Rene P.; Philip M. Gschwend; Dieter M. Imboden (2003). Environmental Organic Chemistry (2 ed.). Wiley Interscience. p. 1052. ISBN 9780471350538.

- Tyus, Harold M. (2012). Ecology and Conservation of Fishes. CRC Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-4398-9759-1.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Bright, Michael, ed. (2010). 1001 natural wonders : you must see before you die. preface by Koichiro Mastsuura (2009 ed.). London: Cassell Illustrated. p. 620. ISBN 9781844036745.

- "Deepest Lake in the World". geology.com. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- Jung, J., Hojnowski, C., Jenkins, H., Ortiz, A., Brinkley, C., Cadish, L., Evans, A., Kissinger, P., Ordal, L., Osipova, S., Smith, A., Vredeveld, B., Hodge, T., Kohler, S., Rodenhouse, N. and Moore, M. (2004). "Diel vertical migration of zooplankton in Lake Baikal and its relationship to body size" (PDF). In Smirnov, A.I.; Izmest'eva, L.R. (eds.). Ecosystems and Natural Resources of Mountain Regions. Proceedings of the first international symposium on Lake Baikal: The current state of the surface and underground hydrosphere in mountainous areas. "Nauka", Novosibirsk, Russia. pp. 131–140. Retrieved 9 August 2009.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Lake Baikal – A Touchstone for Global Change and Rift Studies". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- "Lake Baikal – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- "Lake Baikal: Protection of a unique ecosystem". ScienceDaily. 26 July 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- S. Hudgins (2003). The Other Side of Russia: A Slice of Life in Siberia and the Russian Far East. Texas A&M University Press. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- M. Hammer; T. Karafet (1995). "DNA & the peopling of Siberia". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Fefelov, I.; Tupitsyn, I. (August 2004). "Waders of the Selenga delta, Lake Baikal, eastern Siberia" (PDF). Wader Study Group Bulletin. 104: 66–78. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- "Lake Baikal – World Heritage Site". World Heritage. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- "The Oddities of Lake Baikal". Alaska Science Forum. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- Kravchinsky, V.A., M.A. Krainov, M.E. Evans, J.A. Peck, J.W. King, M.I. Kuzmin, H. Sakai, T. Kawai, and D. Williams. Magnetic record of Lake Baikal sediments: chronological and paleoclimatic implication for the last 6.7 Myr. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 195, 281–298, 2003. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(03)00362-6

- Kravchinsky, V.A., M.E. Evans, J.A. Peck, H. Sakai, M.A. Krainov, J.W. King, M.I. Kuzmin. A 640kyr geomagnetic and paleoclimatic record from Lake Baikal sediments. Geophysical Journal International, 170 (1), 101–116, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03411.x, 2007.

- M.I. Kuzmin et al. (1998). First find of gas hydrates in sediments of Lake Baikal. Doklady Adademii Nauk, 362: 541–543 (in Russian).

- M. Vanneste; M. De Batist; A. Golmshtok; A. Kremlev; W. Versteeg (2001). "Multi-frequency seismic study of gas hydrate-bearing sediments in Lake Baikal, Siberia". Marine Geology. 172 (1): 1–21. Bibcode:2001MGeol.172....1V. doi:10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00117-1.

- P. Van Rensbergen; M. De Batist; J. Klerkx; R. Hus; J. Poort; M. Vanneste; N. Granin; O. Khlystov; P. Krinitsky (2002). "Sublacustrine mud volcanoes and methane seeps caused by dissociation of gas hydrates in Lake Baikal". Geology. 30 (7): 631–634. Bibcode:2002Geo....30..631V. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0631:SMVAMS>2.0.CO;2.

- "Lake Baikal: the great blue eye of Siberia". CNN. Archived from the original on 11 October 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- Touchart, Laurent (2012), Bengtsson, Lars; Herschy, Reginald W.; Fairbridge, Rhodes W. (eds.), "Baikal, Lake", Encyclopedia of Lakes and Reservoirs, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 83–91, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4410-6_50, ISBN 978-1-4020-4410-6, retrieved 18 October 2020

- Freshwater Ecoregions of the World (2008). Lake Baikal. Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Hutter; Yongqi; Chubarenko (2011). Physics of Lakes: Foundation of the Mathematical and Physical Background. 1. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-642-15178-1.

- "Unique body of water". Black Sea Scene. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- "Ice Conditions". bww.irk.ru. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- "Baikal seal". baikal.ru. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- Gurulev, S.A. "Temperature of Lake Baikal Water". bww.irk.ru. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- Pomazkina, G.; L. Kravtsova; E. Sorokovikova (2012). "Structure of epiphyton communities on Lake Baikal submerged macrophytes". Limnological Review. 12 (1): 19–27. doi:10.2478/v10194-011-0041-1.

- Rivarola-Duartea; Otto; Jühling; Schreiber; Bedulina; Jakob; Gurkov; Axenov-Gribanov; Sahyoun; Lucassen; Hackermüller; Hoffmann; Sartoris; Pörtner; Timofeyev; Luckenbach; and Stadler (2014). A First Glimpse at the Genome of the Baikalian Amphipod Eulimnogammarus verrucosus. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 322(3): 177–189.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2009. Marsh Thistle: Cirsium palustre, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Strömberg Archived 13 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Mackay, A.; R. Flower; L. Granina (2002). "Lake Baikal". In Shahgedanova, M. (ed.). The Physical Geography of Northern Eurasia. Oxford University Press. pp. 403–421. ISBN 978-0-19-823384-8.

- Peter Saundry. 2010. Baikal seal. Encyclopedia of Earth. Topic ed. C. Michael Hogan, Ed. in chief C. NCSE, Washington D.C.

- "Wildlife of Lake Baikal". bww.irk.ru. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- Sipko P.T.. 2009. European bison in Russia – past, present and future (pdf). the European Bison Conservation Newsletter Vol 2 (2009). pp.148–159. the Institute of Problems Ecology and Evolution RAS. Retrieved on 31 March 2017

- "Животный мир Байкала. Озеро Байкал: экология. Озеро Байкал. Природа. Пресноводные водоемы, растительность, животный мир". www.zooeco.com. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- Flint, V.E.; R.L. Boehme; Y.V. Kostin; A.A. Kuznetsov (1984). Birds of the USSR. Princeton University Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-691-02430-8.

- BirdLife International (2016). "Bradypterus davidi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2014). "Thymallus baikalensis" in FishBase. April 2014 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2014). "Thymallus brevipinnis" in FishBase. April 2014 version.

- FishBase: Species in Lake Baikal. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Kontula, Tytti; Kirilchik, Sergei V.; Väinölä, Risto (2003). "Endemic diversification of the monophyletic cottoid fish species flock in Lake Baikal explored with mtDNA sequencing". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 27: 143–155. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00376-7. PMID 12679079.

- Hunt, D. M., et al. (1997). Molecular evolution of the cottoid fish endemic to Lake Baikal deduced from nuclear DNA evidence. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 8(3): 415–22.

- Pastukhov, V.D: Lake Baikal Seals – NERPA. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2014). "Coregonus baicalensis" in FishBase. April 2014 version.

- Baikal.ru: Baikal grayling. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Baikal.ru: Baikal sturgeon. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- "Зоопланктон в экосистеме озера Байкал / О Байкале.ру – Байкал. Научно и популярно". Baikal.mobi. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Sacred Sea: A Journey to Lake Baikal

- Sherbakov; Kamaltynov; Ogarkov; and Verheyen (1998). Patterns of Evolutionary Change in Baikalian Gammarids Inferred from DNA Sequences (Crustacea, Amphipoda). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 10(2): 160–167

- BBC News (13 May 1999). Oxygen boosts polar giants. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- Daneliya, M.E.; Kamaltynov, R.M.; and Väinölä, R. (2011). Phylogeography and systematics of Acanthogammarus s. str., giant amphipod crustaceans from Lake Baikal. Zoologica Scripta 40(6): 623–637.

- Karanovic, I.; and T.Y. Sitnikova (2017). Morphological and molecular diversity of Lake Baikal candonid ostracods, with a description of a new genus. Zookeys. 2017(684): 19–56. doi:10.3897/zookeys.684.13249

- Martens; Schön; Meisch; and Horne (2008). Global diversity of ostracods (Ostracoda, Crustacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 595: 185–193. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9245-4

- Karanovic, I.; and T.Y. Sitnikova (2017). Phylogenetic position and age of Lake Baikal candonids (Crustacea, Ostracoda) inferred from multigene sequence analyzes and molecular dating. Ecol Evol. 7(17): 7091–7103. doi:10.1002/ece3.3159

- Schön; Pieri; Sherbakov; and Martens (2017). Cryptic diversity and speciation in endemic Cytherissa (Ostracoda, Crustacea) from Lake Baikal. Hydrobiologia 800(1): 61–79. doi:10.1007/s10750-017-3259-3

- Sitnikova, T.Y. (2006). "Endemic gastropod distribution in Baikal". Hydrobiologia. 568 (S1): 207–211. doi:10.1007/s10750-006-0313-y. S2CID 35020631.

- Baikal.ru: Gastropoda. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- Slugina, Z.V. (2006). "Endemic Bivalvia in ancient lakes". Hydrobiologia. 568 (S1): 213–217. doi:10.1007/s10750-006-0312-z. S2CID 22330810.

- Slugina; Starobogatov; and Korniushin (1994). Bivalves (Bivalvia) of Lake Baikal. Ruthenica 4(2): 111-146.

- Segers, H.; and Martens, K; editors (2005). The Diversity of Aquatic Ecosystems. pp. 43–44. Developments in Hydrobiology. Aquatic Biodiversity. ISBN 1-4020-3745-7

- Kaygorodova, I.A.; and N.M. Pronin (2013). New Records of Lake Baikal Leech Fauna: Species Diversity and Spatial Distribution in Chivyrkuy Gulf. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013(2013): 206590. doi:10.1155/2013/206590

- Baikal.ru: Flatworms (Plathelminthes). Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Kaluzhnaya; Belikov; Schröder; Rothenberger; Zapf; Kaandorp; Borejko; Müller; and Müller (2005). Dynamics of skeleton formation in the Lake Baikal sponge Lubomirskia baicalensis. Part I. Biological and biochemical studies. Naturwissenschaften 92: 128–133.

- Paradina; Kulikova; Suturin; and Saibatalova (2003). The Distribution of Chemical Elements in Sponges of the Family Lubomirskiidae in Lake Baikal. International Symposium – Speciation in Ancient Lakes, SIAL III – Irkutsk 2002. Berliner Paläobiologische Abhandlungen 4: 151–157.

- Belikov; Kaluzhnaya; Schröder; Müller; and Müller (2007). Lake Baikal endemic sponge Lubomirskia baikalensis: structure and organization of the gene family of silicatein and its role in morphogenesis. Porifera Research: Biodiversity, Innovation and Sustainability, pp. 179–188.

- Kozhov, M. (1963). Lake Baikal and Its Life. Monographiae Biologicae. 11. pp. 63–67. ISBN 978-94-015-7388-7.

- Müller; and Grachev, eds. (2009). Biosilica in Evolution, Morphogenesis, and Nanobiotechnology: Case Study Lake Baikal, pp. 81–110. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-3-540-88551-1.

- Lincoln, W.B. (2007). The Conquest of a Continent: Siberia and the Russians. Cornell University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-8014-8922-8.

- Chang, Chun-shu (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Nation, State, and Imperialism in Early China, ca. 1600 B.C.-A.D. 8. University of Michigan Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-472-11533-4.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce (2007). The Conquest of a Continent: Siberia and the Russians. Cornell University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-8014-8922-8.

- "Research of the Baikal". Irkutsk.org. 18 January 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- George V. Lantzeff and Richard A. Price, 'Eastward to Empire',1973

- Открытие Русскими Средней И Восточной Сибири (in Russian). Randewy.ru. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- "Irkutsk Hydroelectric Power Station History". Irkutskenergo. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- Байкальский исследовательский центр (Baikal Research Centre; in Russian). www.baikal-research.org

- "Russians in landmark Baikal dive". BBC News. 29 July 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- Gallant, Jeffrey (29 July 2008) "Russian submersible dives in Lake Baikal do not establish new freshwater depth record". Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2009.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). DivingAlmanac.com

- PA News (19 July 2008). "Submarines to plumb deepest lake".

- Barry, Ellen (23 May 2011). "A Rugged Guys' heart to heart". International Herald Tribune.

- "Baikal Lake Neutrino Telescope". Baikalweb. 6 January 2005. Archived from the original on 31 August 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- "Lake Baikal". Global Great Lakes. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Tom Esslemont (7 September 2007). ""Pearl of Siberia" draws investors". BBC News. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- Daniil, Timin. "Driving on frozen Lake Baikal in the winter". Russian blogger.

- "Lake Baikal Travel Guide – Top Ten Attractions on Lake Baikal". 23 November 2017.

- "A Winter Bikepacking Journey Across Lake Baikal". BIKEPACKING.com. 18 May 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- https://greatbaikaltrail.org/en/tropi/

- "Самый теплый залив на Байкале – Чивыркуйский залив !". 17 December 2017.

- McGee, Rylin (17 April 2018). "Ecotourism in Siberia: Development and Challenges on Olkhon Island". GeoHistory. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Chinese tourists eager to visit Baikal". 18 March 2015.

- France-Presse, Agence (19 October 2017). "World's deepest lake crippled by putrid algae, poaching and pollution". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Brown, Kate Pride (2018). Saving the Sacred Sea: The Power of Civil Society in an Age of Authoritarianism and Globalization. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190660949.

- Sobisevich A. V., Snytko V. A. Some aspects of nature protection in the scientific heritage of academician Innokentiy Gerasimov // Acta Geographica Silesiana. 2018. Vol. 29, # 1. P. 55–60.

- Tom Parfitt in Moscow (12 November 2008). "Russia Water Pollution". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- "Sacred Land Film Project, Lake Baikal". Sacredland.org. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- "Economic crisis saves Lake Baikal from pollution". Russiatoday.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Clifford J. Levy (11 September 2010). "Russia Uses Microsoft to Suppress Dissent". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "Russians Debate Fate of Lake: Jobs Or Environment?". Npr.org. 10 May 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Tide of discontent sweeps through Russia's struggling 'rust belt' – NBC News Archived 15 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Worldnews.nbcnews.com (30 November 2013). Retrieved on 15 May 2014.

- "Байкальский ЦБК остановил производство". 16 September 2013.

- "Transneft". Transneft. Archived from the original on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- "Baikal Environmental Wave". Archived from the original on 25 August 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- "Baikal pipeline". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- "The Right to Know: Irkutsk Citizens Want to be Consulted". Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- "Тема: (ENWL) Власти Иркутской обл. выступили против прокладки нефтепровода к Тихому океану". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- "Putin orders oil pipeline shifted". BBC News. 26 April 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- "Transneft charged with Siberia-Pacific pipeline construction". BizTorg.ru. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- "New route". Transneft Press Center. Archived from the original on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- "Work starts on Russian pipeline". BBC News. 28 April 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- "Saving the Sacred Sea: Russian nuclear plant threatens ancient lake". Newint.org. 2 May 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- "The International Uranium Enrichment Center | JSC IUEC". eng.iuec.ru. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- "Siberian Authorities Halt Construction of Lake Baikal Bottling Plant After Backlash". 15 March 2019.

- "StephenMBland". StephenMBland.

- Russia's Baikal, Biggest Lake in the World, 'Becoming a Swamp'. 8 September 2014 19:35. The Moscow Times.

- Raymond H. Fisher, The Voyage of Semon Dezhnev, The Haklyut Society, 1981, p. 246 ISBN 0904180123

- Tooke, William (1800). View of the Russian empire during the reign of Catharine the Second, and to the close of the eighteenth century. Printed by A. Strahan, for T. N. Longman and O. Rees. p. 203.

- "On the Baikal Sea I was in a shipwreck again" (На Байкалове море паки тонул), in the Life of Protopope Avvakum, Written by Himself (Житие протопопа Аввакума, им самим написанное)

- L. Bagrov (1964). International Society for the History of Cartography (ed.). Imago mundi. 1. Brill Archive. p. 115.

- Lake Baikal: Siberia's Great Lake ISBN 978-1-84162-294-1 p. 4

- T. W. Atkinson (1861). Travels in the Regions of the Upper and Lower Amoor. Hurst and Blackett. p. 385.

- "The Glorious Sea, Sacred Baikal". Karaoke.ru. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- «По диким степям Забайкалья», Русланова Лидия. karaoke.ru (in Russian)

Literature

- Detlev Henschel: Kayak Adventure in Siberia: The first solo circumnavigation of Lake Baikal. Amazon ISBN 978-3-7375-6102-0.

- Colin Thubron In Siberia, https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/006095373X/ref=cm_sw_r_cp_api_Lj5pAb5G9RF4N

- Leonid Borodin: Year of Miracle And Grief, Quartet Books, 1988.

Martin Cruz Smith: "Siberian Dilemma," Simon & Schuster, 2019

Video

- Lake Baikal on Vimeo