Ljubinje

Ljubinje (Serbian Cyrillic: Љубиње) is a town and municipality located in Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is situated in south-eastern part of Herzegovina region. As of 2013, the town has a population of 2,744 inhabitants, while the municipality has 3,511 inhabitants.

Ljubinje

Љубиње | |

|---|---|

Town and municipality | |

Serbian Orthodox Church of the Nativity of the Virgin in Ljubinje | |

Coat of arms | |

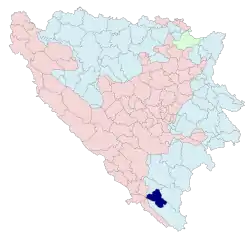

Location of Ljubinje within Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| |

| Coordinates: 42°57′05″N 18°05′25″E | |

| Country | Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Entity | Republika Srpska |

| Boroughs | 21 (2008) |

| Government | |

| • Municipality president | Stevo Drapić (SDS) |

| • Municipality | 319.07 km2 (123.19 sq mi) |

| Population (2013 census) | |

| • Town | 2,744 |

| • Municipality | 3,511 |

| • Municipality density | 11/km2 (28/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code(s) | 59 |

History

Ancient history

In antiquity, a road ran from Narona (near Metković) to Epidaurum (Cavtat) via Pardua, in present-day village Gradac near Ljubinje. The remains of a Roman settlement have been identified near Ljubinje. No systematic expert investigations have been conducted in the area (as of 1973).[1]

Middle Ages

In the early medieval period the area of present-day Ljubinje municipality belonged to the large župa (county) of Popovo, constituting the northernmost part of Popovo county, bordering with the counties of Dubrave and Dabar.[2] Politically, the area belonged to Zahumlje ("Hum"), ruled between the 12th and early 14th century with minor interruptions by the Nemanjić dynasty. After the War of Hum (1326–1329), this part of Hum was occupied by Bosnian Ban Stjepan II Kotromanić, whose heir Tvrtko I had by 1373 extended the Bosnian borders southwards to include all of Hum.[3] Tvrtko's reign saw the rise of the Kosača family, of whom Vlatko Vuković had already by that time begun to rule much of Hum. Hum was governed in the family through Sandalj Hranić (1392–1435), Stjepan Vukčić Kosača (1435–1466), and the latters sons, until 1482.

Ottoman period

The Ottoman Empire occupied the area around Ljubinje between 1465 and 1467, and the defter (tax registry) of the Bosnian sanjak for 1468/69 already included the nahiya of Ljubinje.[4]

Austro-Hungarian rule

Under article 29 of the Treaty of Berlin of 1878, Austria-Hungary received special rights in the Ottoman Empire's provinces of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Sanjak of Novi Pazar. On 14 August 1878,[5] Austro-Hungarian army marched in Ljubinje, ending Ottoman rule in the region. On 6 October 1908, Emperor Franz Joseph announced to the people of Bosnia-Herzegovina his intention to give them an autonomous and constitutional regime and the provinces were annexed. Bosnian annexation was not countenanced by the Treaty of Berlin and set off a flurry of diplomatic protests and discussions.[6] Ljubinje remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the liberation at the end of World War I, when the Serbian army marched into Ljubinje.

World War II

In June 1941 Ustaše soldiers killed 36 locals by throwing them live in a massive grave, which was a part of the wider Genocide of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia.[7][8]

Culture

Church of the Nativity of the Virgin

The Serbian Orthodox church of the Nativity of the Virgin in Ljubinje, was built between in 1867 (as recorded by the inscription incised on a plaque above the entrance to the church). The Church belongs to the type of Herzegovina single-nave stone-built church with semicircular apse and stone belltower of the type known as "na preslicu", perched over the main entrance facade.[9] A belltower na preslicu with three bells, made of finely finished limestone blocks, tops the west wall of the church. Belltowers of this form are one of the main characteristics of churches of this type in Herzegovina. The church is roofed with industrial tiles. Only the ends of the roof panes (by the belltower and the apse respectively) are clad with sheet copper. The apse is also clad with sheet copper. The nave is separated from the altar space by an iconostasis partition. The iconostasis of the church of the Nativity of the Most Holy Virgin in Ljubinje was installed in the early 20th century. The artist who painted the icons remains unidentified. The frame of the iconostasis is wooden, and to it are attached the icons, paintings on canvas with various scenes. The church contains a copy of the Gospels dating from 1793, in a metal cover with two metal clasps to the side, donated from Russia along with double-sided processional icon, made of copper, by Zorka Radonjić (1901).[10] The centre of one side of the processional icon is occupied by an embossed and engraved scene of the Nativity of Christ, and the other by the Evangelist Luke, also embossed and engraved.

To the north, east and west, the church is surrounded by an Orthodox cemetery in active use, and Necropolis with stećak tombstones. About 20 metres to the north of the church is a mausoleum in memory of World War II victims of fascist terror.

The Commission to Preserve National Monuments in 2005 issued a decision to add the architectural ensemble of the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin in Ljubinje to the List of National Monuments.[11]

Church of the Nativity of the Lord Jesus Christ

The Serbian Orthodox Church of the Nativity of the Lord Jesus Christ in Ljubinje was designed by Serbian architect Ljubiša Folić.[12] Church was named after the Nativity of Christ for the fact that its construction started in 2000, an important year in Christianity that actually commemorates its most important event and the reason why it exists in the first place. Completion of the work and consecration of the new Orthodox Cathedral was solemnly celebrated on 21 September 2004, on patron Saint’s Day of Ljubinje municipality (The feast day of the Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos ). The Holy Hierarchal Liturgy was served by episcope of Zahumlje, Herzegovina and the Littoral Grigorije.[10]

Demographics

Population

| Population of settlements – Ljubinje municipality | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Settlement | 1879. | 1885. | 1895. | 1910. | 1921. | 1931. | 1948. | 1953. | 1961. | 1971. | 1981. | 1991. | 2013. | |

| Total | 10,283 | 11,381 | 12,238 | 14,606 | 14,422 | 14,980 | 4,837 | 4,516 | 4,172 | 3,511 | ||||

| 1 | Bančići | 113 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Dubočica | 160 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Gleđevci | 74 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Grablje | 81 | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Gradac | 65 | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Ivica | 99 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | Kapavica | 42 | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Krajpolje | 134 | ||||||||||||

| 9 | Krtinje | 51 | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Kruševica | 233 | ||||||||||||

| 11 | Ljubinje | 503 | 469 | 621 | 796 | 1,660 | 2,265 | 2,744 | ||||||

| 12 | Mišljen | 65 | ||||||||||||

| 13 | Obzir | 48 | ||||||||||||

| 14 | Pocrnje | 37 | ||||||||||||

| 15 | Pustipusi | 64 | ||||||||||||

| 16 | Rankovci | 33 | ||||||||||||

| 17 | Ubosko | 142 | ||||||||||||

| 18 | Vlahovići | 169 | ||||||||||||

| 19 | Vođeni | 153 | ||||||||||||

| 20 | Žabica | 45 | ||||||||||||

| 21 | Žrvanj | 99 | ||||||||||||

Ethnic composition

| Ethnic composition – Ljubinje town | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013. | 1991. | 1981. | 1971. | ||||

| Total | 2,744 (100,0%) | 2,265 (100,0%) | 1,660 (100,0%) | 796 (100,0%) | |||

| Serbs | 2,114 (93,33%) | 1,448 (87,23%) | 710 (89,20%) | ||||

| Bosniaks | 103 (4,547%) | 74 (4,458%) | 49 (6,156%) | ||||

| Others | 28 (1,236%) | 1 (0,060%) | |||||

| Yugoslavs | 17 (0,751%) | 107 (6,446%) | 16 (2,010%) | ||||

| Croats | 3 (0,132%) | 5 (0,301%) | 5 (0,628%) | ||||

| Montenegrins | 22 (1,325%) | 8 (1,005%) | |||||

| Albanians | 3 (0,181%) | ||||||

| Roma | 8 (1,005%) | ||||||

| Ethnic composition– Ljubinje municipality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013. | 1991. | 1981. | 1971. | ||||

| Total | 3,511 (100,0%) | 4,172 (100,0%) | 4,516 (100,0%) | 4,837 (100,0%) | |||

| Serbs | 3,469 (98,80%) | 3,748 (89,84%) | 3,840 (85,03%) | 4,170 (86,21%) | |||

| Others | 20 (0,570%) | 34 (0,815%) | 11 (0,244%) | 16 (0,331%) | |||

| Bosniaks | 12 (0,342%) | 332 (7,958%) | 407 (9,012%) | 532 (11,00%) | |||

| Croats | 10 (0,285%) | 39 (0,935%) | 55 (1,218%) | 62 (1,282%) | |||

| Yugoslavs | 19 (0,455%) | 159 (3,521%) | 17 (0,351%) | ||||

| Montenegrins | 24 (0,531%) | 16 (0,331%) | |||||

| Roma | 17 (0,376%) | 8 (0,165%) | |||||

| Albanians | 3 (0,066%) | 1 (0,021%) | |||||

| Slovenes | 13 (0,269%) | ||||||

| Macedonians | 2 (0,041%) | ||||||

Economy

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2018):[13]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 80 |

| Mining and quarrying | - |

| Manufacturing | 48 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 19 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 13 |

| Construction | 4 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 70 |

| Transportation and storage | 8 |

| Accommodation and food services | 39 |

| Information and communication | 85 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 5 |

| Real estate activities | - |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 8 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 3 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 71 |

| Education | 78 |

| Human health and social work activities | 25 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 8 |

| Other service activities | 7 |

| Total | 571 |

Notable residents

- Đorđe Đurić, Serbian volleyball player, Olympic bronze medalist

- Gojko Đogo, poet and dissident

- Miroslav Toholj, writer and politician, Information Minister, Minister without portfolio (Government of Republika Srpska)

- Nektarije Krulj, Metropolitan Bishop of Dabar and Bosnia (Serbian Orthodox Church)

- Admir Vladavić, football player

See also

Notes

- Bojanovski (1973: 137-187)

- Anđelić (1983: 8–69)

- Ćirković (1964: 88–90, 162)

- Aličić (1985: various).

- "Tardy Peace In The Orient - Austria'S Struggle With Bonnia. The So-Called Insurgents Fighting Obstinately-Mehemet Ali'S Mission To The Provinces-Austrian Suspicion Of Servia And Panslavism-Hungarian Restriction On The Sale Of Arms. - View Article - Nytimes.Com" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- Albertini (2005: 218–219).

- "ЈАМА ПАНДУРИЦА, 13. ЈУН 2019. ГОДИНЕ: Помен за 36 мученика страдалих од усташа". Слободна Херцеговина (in Serbian). 2019-06-12. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- "Ustaški holokaust nad Srbima u Hercegovini | Herceg Televizija Trebinje". www.herceg.tv. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- "Commission to preserve national monuments". Kons.gov.ba. Archived from the original on 2013-10-14. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- "Епархија ЗХиП - ПАРОХИЈА ЉУБИЊСКА | Епархија захумско-херцеговачка и приморска". Arhiva.eparhija-zahumskohercegovacka.com. 1982-04-13. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- "Commission to preserve national monuments". Kons.gov.ba. Archived from the original on 2013-10-14. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- Milan Maksimovic. "Folic Archiitects - Portfolio - Religious - St. Resurection Cathedral". Folicarchitects.com. Archived from the original on 2013-03-26. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- "Cities and Municipalities of Republika Srpska" (PDF). rzs.rs.ba. Republika Srspka Institute of Statistics. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Secondary sources

- Anđelić, Pavao. 1983. Srednjovjekovna župa Popovo (The mediaeval county of Popovo), Tribunia, no. 7, Trebinje.

- Ćirković, Simo. 1964. Istorija srednjovjekovne bosanske države (History of the mediaeval Bosnian state), Belgrade.

- Aličić, Ahmed. 1985. Poimenični popis sandžaka vilajeta Hercegovina.(Name lists of the sandžak of the vilayet of Herzegovina) Oriental Institute in Sarajevo, Sarajevo.

- Albertini, Luigi. 2005. Origins of the War of 1914 – Vol. 1, Enigma Books, New York.

- Bojanovski, Ivo. 1973. Rimska cesta Narona - Leusinium kao primjer saobraćajnog kontinuiteta. Godišnjak ANUBiH, Centar za balkanološka ispitivanja 10/8, Sarajevo.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ljubinje Municipality. |