Lucha libre

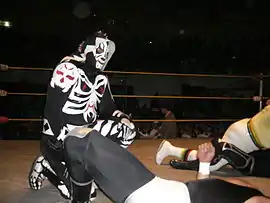

Lucha libre (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈlutʃa ˈliβɾe], meaning "freestyle wrestling"[1] or literally translated as "free fight") is the term used in Mexico for professional wrestling. Since its introduction to Mexico in the early 20th century, it has developed into a unique form of the genre, characterized by colorful masks, rapid sequences of holds and maneuvers, as well as "high-flying" maneuvers, some of which have been adopted in the United States and elsewhere. The wearing of masks has developed special significance, and matches are sometimes contested in which the loser must permanently remove his mask, which is a wager with a high degree of weight attached. Tag team wrestling is especially prevalent in lucha libre, particularly matches with three-member teams, called trios.

Although the term today refers exclusively to professional wrestling, it was originally used in the same style as the American and English term "freestyle wrestling",[2][3][4] referring to an amateur wrestling style without the restrictions of Greco-Roman wrestling.

Lucha libre wrestlers are known as luchadores (singular luchador, meaning "wrestler"). They usually come from extended wrestling families who form their own stables. One such line integrated to the United States professional wrestling scene is Los Guerreros.

Lucha libre has become a loanword in English, as evidenced by works such as Los Luchadores, ¡Mucha Lucha!, Lucha Mexico and Nacho Libre. Lucha libre also appears in other pop culture such as mainstream advertising: in Canada, Telus' Koodo Mobile Post Paid cell service uses a cartoon lucha libre wrestler as its spokesperson/mascot.

On July 21, 2018, Mexican Lucha libre was declared an intangible cultural heritage of Mexico City.[5]

Rules

The rules of lucha libre are similar to American singles matches. Matches can be won by pinning the opponent to the mat for the count of three, making him submit, knocking him out of the ring for a predetermined count (generally twenty) or by disqualification. Using the ropes for leverage is illegal, and once a luchador is on the ropes, his opponent must release any holds and he will not be able to pin him.

Disqualifications occur when an opponent uses an illegal hold, move (such as the piledriver, which is an illegal move in lucha libre and grounds for immediate disqualification, though some variations are legal in certain promotions), or weapon, hits his opponent in the groin (faul), uses outside interference, attacks the referee, or rips his opponent's mask completely off. Most matches are two out of three falls (dos de tres caídas), which had been abandoned for title bouts in North America and Japan in the 1970s.

A rule unique to lucha libre applies during tag team matches, which is when the legal wrestler of a team touches the floor outside the ring, a teammate may enter the ring to take his place as the legal competitor. As the legal wrestler can step to the floor willingly, there is essentially no need for an actual tag to a teammate to bring him into a match. This often allows for much more frenetic action to take place in the ring than would otherwise be possible under standard tag rules.

History

The antecedents of Mexican wrestling date back to 1863, during the French Intervention in Mexico, Enrique Ugartechea, the first Mexican wrestler, developed and invented the Mexican lucha libre from the Greco-Roman wrestling.[6][7]

.jpg.webp)

In the early 1900s, professional wrestling was mostly a regional phenomenon in Mexico until Salvador Lutteroth founded the Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre (Mexican Wrestling Enterprise) in 1933, giving the sport a national foothold for the first time. The promotion flourished and quickly became the premier spot for wrestlers. As television surfaced as a viable entertainment medium during the 1950s, Lutteroth was then able to broadcast his wrestling across the nation, subsequently yielding a popularity explosion for the sport. Moreover, it was the emergence of television that allowed Lutteroth to promote lucha libre's first breakout superstar into a national pop-culture phenomenon.[8]

In 1942, lucha libre would be forever changed when a silver-masked wrestler, known simply as El Santo (The Saint), first stepped into the ring. He made his debut in Mexico City by winning an 8-man battle royal. The public became enamored by the mystique and secrecy of Santo's personality, and he quickly became the most popular luchador in Mexico. His wrestling career spanned nearly five decades, during which he became a folk hero and a symbol of justice for the common man through his appearances in comic books and movies, while the sport received an unparalleled degree of mainstream attention.[9]

Other legendary luchadores who helped popularize the sport include Gory Guerrero, who is credited with developing moves and holds which are now commonplace in professional wrestling; Blue Demon, a contemporary of Santo and possibly his greatest rival; and Mil Máscaras (Man of A Thousand Masks), who is credited with introducing the high flying moves of lucha libre to audiences around the world. He achieved international fame as one of the first high-flyers, something he was not considered in Mexico, where he fell under the mat-power category.[10][11][12]

Style of wrestling

Luchadores are traditionally more agile and perform more aerial maneuvers than professional wrestlers in the United States, who more often rely on power and hard strikes to subdue their opponents. The difference in styles is due to the independent evolution of the sport in Mexico beginning in the 1930s and the fact that luchadores in the cruiserweight division (peso semicompleto) are often the most popular wrestlers in Mexican lucha libre.[13] Luchadores execute characteristic high flying attacks by using the wrestling ring's ropes to catapult themselves towards their opponents, using intricate combinations in rapid-fire succession, and applying complex submission holds. Rings used in lucha libre generally lack the spring supports added to U.S. and Japanese rings; as a result, lucha libre does not emphasize the "flat back" bumping style of other professional wrestling styles. For this same reason, aerial maneuvers are almost always performed to opponents outside the ring, allowing the luchador to break his fall with an acrobatic tumble.

Lucha libre has several different weight classes, many catered to smaller agile fighters, who often make their debuts in their mid-teens. This system enables dynamic high-flying luchadores such as Rey Mysterio, Jr., Juventud Guerrera, Super Crazy and Místico, to develop years of experience by their mid-twenties.[14] A number of prominent Japanese wrestlers also started their careers training in Mexican lucha libre before becoming stars in Japan. These include Gran Hamada, Satoru Sayama, Jushin Thunder Liger, and Último Dragón.

Lucha libre is also known for its tag team wrestling matches. The teams are often made up of three members, instead of two as is common in the United States. These three man teams participate in what are called trios matches, for tag team championship belts. Of these three members, one member is designated the captain. A successful fall in a trios match can be achieved by either pinning the captain of the opposing team or by pinning both of the other members. A referee can also stop the match because of "excessive punishment". He can then award the match to the aggressors. Falls often occur simultaneously, which adds to the extremely stylized nature of the action. In addition, a wrestler can opt to roll out of the ring in lieu of tagging a partner or simply be knocked out of the ring, at which point one of his partners may enter. As a result, the tag team formula and pacing which has developed in U.S. tag matches is different from lucha libre because the race to tag is not a priority. There are also two-man tag matches (parejas), as well as "four on four" matches (atomicos).[15]

Masks

Masks (máscaras) have been used dating back to the beginnings of lucha libre in the early part of the 20th century, and have a historical significance to Mexico in general, dating to the days of the Aztecs.[16] Early masks were very simple with basic colors to distinguish the wrestler. In modern lucha libre, masks are colorfully designed to evoke the images of animals, gods, ancient heroes and other archetypes, whose identity the luchador takes on during a performance. Virtually all wrestlers in Mexico will start their careers wearing masks, but over the span of their careers, a large number of them will be unmasked. Sometimes, a wrestler slated for retirement will be unmasked in his final bout or at the beginning of a final tour, signifying loss of identity as that character. Sometimes, losing the mask signifies the end of a gimmick with the wrestler moving on to a new gimmick and mask. The mask is considered sacred to a degree, so much so that fully removing an opponent's mask during a match is grounds for disqualification.[17]

During their careers, masked luchadores will often be seen in public wearing their masks and keeping up the culture of Lucha Libre, while other masked wrestlers will interact with the public and press normally. However, they will still go to great lengths to conceal their true identities; in effect, the mask is synonymous with the luchador. El Santo continued wearing his mask after retirement, revealed his face briefly only in old age, and was buried wearing his silver mask.

More recently, the masks luchadores wear have become iconic symbols of Mexican culture. Contemporary artists like Francisco Delgado and Xavier Garza incorporate wrestler masks in their paintings.[18]

Although masks are a feature of lucha libre, it is a misconception that every Mexican wrestler uses one. There have been several maskless wrestlers who have been successful, particularly Tarzán López, Gory Guerrero, Perro Aguayo and Negro Casas. Formerly masked wrestlers who lost their masks, such as Satánico, Cien Caras, Cibernético and others, have had continued success despite losing their masks.

Luchas de apuestas

With the importance placed on masks in lucha libre, losing the mask to an opponent is seen as the ultimate insult, and can at times seriously hurt the career of the unmasked wrestler. Putting one's mask on the line against a hated opponent is a tradition in lucha libre as a means to settle a heated feud between two or more wrestlers. In these battles, called luchas de apuestas ("matches with wagers"), the wrestlers "wager" either their mask or their hair.[19]

"In a lucha de apuesta (betting match), wrestlers make a public bet on the outcome of the match. The most common forms are the mask-against-mask, hair-against-hair, or mask-against-hair matches. A wrestler who loses his or her mask has to remove the mask after the match. A wrestler who loses their hair is shaved immediately afterward."[20] If the true identity of a person losing his mask is previously unknown, it is customary for that person to reveal his real name, hometown and years as a professional upon unmasking.

The first lucha de apuestas was presented on July 14, 1940 at Arena México. The defending champion Murciélago (Velázquez) was so much lighter than his challenger (Octavio Gaona), he requested a further condition before he would sign the contract: Octavio Gaona would have to put his hair on the line. Octavio Gaona won the match and Murciélago unmasked, giving birth to a tradition in lucha libre.[21]

Variants

- Máscara contra máscara ("mask versus mask"): two masked luchadores bet their masks, the loser is unmasked by the winner.

- Máscara contra cabellera ("mask versus hair"): a masked wrestler and an unmasked one compete, sometimes after the unmasked one has lost his mask to the masked one in a prior bout. If the masked luchador wins, the unmasked one shaves his head as a sign of humiliation. If the unmasked luchador is the winner, he keeps his hair and the loser is unmasked. An example of this variation occurred at Over the Limit 2010, the match was Rey Mysterio versus CM Punk, Mysterio won the match, and Punk got his head shaved.

- Cabellera contra cabellera ("hair versus hair"): the loser of the match has his head shaved bald. This can occur both between unmasked wrestlers and between masked wrestlers who have to remove their mask enough to be shaved after the match. An example of this occurred in the WWF, where Roddy Piper defeated Adrian Adonis at WrestleMania III.

- Máscara o cabellera contra campeonato ("mask or hair versus title"): if the title challenger loses, they are unmasked or shaved. But if the champion loses, the challenger is crowned the new champion. An example of this occurred in WWE, where Rey Mysterio, a masked luchador, beat the Intercontinental Champion Chris Jericho at The Bash. A different result happened on Raw in 2003, where Kane failed to defeat Triple H for the World Heavyweight Championship, and unmasked per the stipulation.

- Máscara o cabellera contra retiro ("mask or hair versus career"): if the masked or haired luchador loses, his opponent wins the mask or hair. But if he wins, his opponent must retire.

- Carrera contra carrera ("career versus career"): Loser must retire. An example of this occurred in the WWF, where The Ultimate Warrior defeated "Macho Man" Randy Savage at WrestleMania VII.

- Apuesta por el nombre ("bet for the name"): A rare case, two luchadores with the same or similar name battle among them for the right to use a name or identity. This occurs mostly when the original luchador leaves a wrestling company but the company retains the name and character (often despite the disagreement of the luchador) and the company gives that gimmink to another luchador. If after a while the original owner returns to the company, it's frequent that he or she claims to be the rightful owner of that character, and adopts a similar name, if the conditions allows it, this can be solved in a "lucha de apuesta" where the winner is considered the rightful owner of the character. Sometimes, but not necessarily, it may also result in the loss of the mask for the looser. The most notorious example are the two bouts (with the first match being controversial and thus anulated) in 2010 of Adolfo Tapia (AKA, L.A. Park, a word play for "la auténtica parca", i.e. "the autentic parca" in spanish) against Jesús Alfonso Huerta (AKA. La Parka, La Parka II), in which Tapia (the original Parka) failed to recover the name, and Huerta retained the identity until his death in 2020. Another example is Mr. Niebla from Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre (Efrén Tiburcio Márquez) who win the name and mask bet against Mr. Niebla from IWRG (Miguel Ángel Guzmán Velázquez).

Weight classes

Since Lucha Libre has its roots more in Latin American professional wrestling than North American professional wrestling it retains some of the basics of the Latin American version such as more weight classes than professional wrestling in North America post World War II. Like "old school" European (especially British) wrestling, some Japanese wrestling and early 20th century American wrestling,[22] Lucha Libre has a detailed weight class system patterned after boxing. Each weight class has an official upper limit, but examples of wrestlers who are technically too heavy to hold their title can be found. The following weight classes exist in Lucha Libre, as defined by the "Comisión de Box y Lucha Libre Mexico D.F." (the Mexico City Boxing and Wrestling Commission), the main regulatory body in Mexico:[23]

| English name | Spanish name | Weight Top Limit | Division Titles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavyweight | Peso Completo | Unlimited | National | CMLL | AAA | UWA | NWA | IWRG | WWA |

| Cruiserweight / Junior Heavyweight | Peso Crucero / Peso Junior-Completo | 105 kg (231 lb) | National | AAA | UWA | NWA | |||

| Light Heavyweight | Peso Semicompleto | 97 kg (214 lb) | National | CMLL | UWA | NWA | WWA | ||

| Super Middleweight / Junior Light Heavyweight | Peso Super Medio / Peso Semicompleto Junior | 92 kg (203 lb) | UWA | WWA | |||||

| Middleweight | Peso Medio | 87 kg (192 lb) | National | CMLL | UWA | NWA | IWRG | WWA | |

| Super Welterweight | Peso Super Wélter | 82 kg (181 lb) | IWRG | ||||||

| Welterweight | Peso Wélter | 77 kg (170 lb) | National | CMLL | UWA | NWA | IWRG | WWA | |

| Super Lightweight | Peso Super Ligero | 73 kg (161 lb) | CMLL | ||||||

| Lightweight | Peso Ligero | 70 kg (150 lb) | National | CMLL | UWA | IWRG | WWA | ||

| Featherweight | Peso Pluma | 63 kg (139 lb) | National | UWA | |||||

| Bantamweight | Peso Gallo | 57 kg (126 lb) | |||||||

| Flyweight | Peso Mosca | 52 kg (115 lb) | |||||||

| Mini-Star | Mini-Estrella | Shorts Wrestlers | National | CMLL | AAA | WWA | |||

| Micro-Star | Micro-Estrella | Dwarfism Wrestlers | CMLL | NWA | |||||

Other characteristics

Luchadores are traditionally divided into two categories, rudos (lit. "tough guys", who are "bad guys", or "heels"), who bend or break the rules, and técnicos (the "good guys", or "faces", literally "technicians"), who play by the rules and their moves are much more complex and spectacular. Técnicos tend to have very formal combat styles, close to Greco-Roman wrestling and martial arts techniques, whereas rudos tend to be brawlers. Técnicos playing the "good guy" role, and rudos playing the "bad guy" role is very characteristic of Mexican lucha libre, which differs from U.S. professional wrestling, where many technical wrestlers play the role of heels (e.g., Kurt Angle), and many brawlers play as "faces" (e.g., Stone Cold Steve Austin & The Rock).[24] Although rudos often resort to using underhanded tactics, they are still expected to live up to a luchador code of honor. For instance, a luchador who has lost a wager match would prefer to endure the humiliation of being unmasked or having his head shaved rather than live with the shame that would come from not honoring his bet. Rudos have also been known to make the transition into técnicos after a career defining moment, as was the case with Blue Demon, who decided to become a técnico after his wrestling partner, Black Shadow, was unmasked by the legendary Santo. Tag teams are sometimes composed of both rudos and técnicos in what are called parejas increibles (incredible pairings). Parejas increibles highlight the conflict between a luchador's desire to win and his contempt for his partner.[25]

A staple gimmick present in lucha libre since the 1950s is exótico, a character in drag. It is argued that the gimmick has recently attained a more flamboyant outlook.[26]

Luchadores, like their foreign counterparts, seek to obtain a campeonato (championship) through winning key wrestling matches. Since many feuds and shows are built around luchas de apuestas (matches with wagers), title matches play a less prominent role in Mexico than in the U.S. Titles can be defended as few as one time per year.[27]

The two biggest lucha libre promotions in Mexico are Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre (CMLL), which was founded in 1933, and Lucha Libre AAA World Wide (AAA).[27]

Fans honoring wrestlers

One characteristic practiced in Mexico is with fans honoring wrestlers by throwing money to the wrestling ring after witnessing a high quality match. With this act fans honor the luchador in a symbolic way, thanking the luchador for a spectacular match demonstrating they are pleased with their performance, showing the match is worth their money and worth more than what they paid for to witness such event. This act of honoring the luchador is uncommon: months can pass without it happening, because fans are the toughest of critics, booing the luchador if they are not pleased with their performance. Booing may happen regardless of the perceived virtuousness of the luchador's persona.

The luchador, after receiving such an act of honor, will pick up the money and save it as a symbolic trophy, putting it in a vase or a box, labeled with the date, to be treasured.

Female professional wrestlers

Female wrestlers or luchadoras also compete in Mexican lucha libre. The CMLL World Women's Championship is the top title for CMLL's women's division, while the AAA Reina de Reinas Championship is a championship defended in an annual tournament by female wrestlers in AAA. AAA also recognizes a World Mixed Tag Team Championship, contested by tag teams composed of a luchador and luchadora respectively. In 2000, the all female promotion company Lucha Libre Femenil (LLF) was founded.[28]

Mini-Estrellas

Lucha Libre has a division called the "Mini-Estrella" or "Minis" division, which unlike North American midget wrestling is not just for dwarfs but also for luchadores that are short. The maximum allowable height to participate in the Mini division was originally 5 feet, but in recent years wrestlers such as Pequeño Olímpico have worked the Minis division despite being 1.69 m (5 ft 6 1⁄2 in) tall.[29] The Minis division was first popularized in the 1970s with wrestlers like Pequeño Luke and Arturito (a wrestler with an R2-D2 gimmick) becoming noticed for their high flying abilities. In the late 1980s/early 1990s CMLL created the first actual "Minis" division, the brainchild of then-CMLL booker Antonio Peña. CMLL created the CMLL World Mini-Estrella Championship in 1992, making it the oldest Minis championship still in existence today.[30] Minis are often patterned after "regular-sized" wrestlers and are sometimes called "mascotas" ("mascots") if they team with the regular-sized version.[29]

Luchadores in the United States

.jpg.webp)

In 1994, AAA promoted the When Worlds Collide pay-per-view in conjunction with the U.S. promotion company World Championship Wrestling (WCW). When Worlds Collide introduced U.S. audiences to many of the top luchadores in Mexico at the time.

In recent years, several luchadores have found success in the United States. Notable luchadores who achieved success in the U.S. are Eddie Guerrero, Chavo Guerrero, Rey Mysterio, Jr., Juventud Guerrera, La Parka, Super Crazy, Alberto Del Rio, Psicosis, Místico, Kalisto, Aero Star, Drago, Andrade "Cien" Almas, Pentagon Jr., Fenix, El Hijo del Fantasma, Bandido, Flamita, Puma King, Rush, Soberano Jr., Dragon Lee, Guerrero Maya Jr. and Stuka Jr.

CMLL Lucha libre shows are broadcast weekly in the U.S. on the Galavisión and LA TV Spanish language cable networks.

Lucha Underground is a television series produced by the United Artists Media Group which airs in English on the El Rey Network and in Spanish on UniMás. It features wrestlers from the American independent circuit and AAA.[31] AAA also owns a percentage of Lucha Underground.[32] The series, which is taped live in Boyle Heights, California, finished season 4 finale.

In 2012, the Arizona Diamondbacks Major League Baseball team started doing promotions involving Lucha Libre. A luchador mask in Diamondback colors was a popular giveaway at one game. In 2013 a Diamondbacks Luchador was made an official mascot, joining D. Baxter Bobcat. The first 20,000 fans at the July 27 game against the San Diego Padres were to receive a luchador mask.

National variants

In Peru the term "cachascán" (from "catch as can") is used. Wrestlers are called cachascanistas.[33] In Bolivian Lucha Libre, wrestling Cholitas – female wrestlers dressed up as indigenous Aymara – are popular,[34][35] and have even inspired comic books.

Promotions using lucha libre rules

Australia

- Lucha Fantastica[36]

Colombia

- Society Action Wrestling (SAW)

Mexico

- Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre (CMLL)

- Lucha Libre AAA Worldwide (AAA)

- International Wrestling Revolution Group (IWRG)

- Universal Wrestling Association (defunct)

- World Wrestling Association (Promociones Mora)

- Lucha Libre Elite

- The Crash Lucha Libre

- Alianza Universal De Lucha Libre

- Other Promotions

Japan

United Kingdom

- Lucha Britannia

- Lucha Libre World

United States

- Chikara

- Incredibly Strange Wrestling

- Invasion Mundial de Lucha Libre

- Lucha Libre USA

- Lucha VaVOOM

- Lucha Underground

In mixed martial arts

Some lucha libre wrestlers had careers in various mixed martial arts promotions, promoting lucha libre and wearing signature masks and attire. One of the most famous is Dos Caras Jr.[37]

In popular culture

Lucha libre has crossed over into popular culture, especially in Mexico where it is the second most popular sport after football.[38] Outside of Mexico Lucha Libre has also crossed over into popular culture, especially in movies and television. Depictions of luchadors are often used as symbols of Mexico and Mexican culture in non-Spanish speaking cultures.

The DC Comics supervillain Bane's costume includes a luchador mask.

The character Mask de Smith from the video game killer7 is a lucha libre wrestler, featuring a mask and cape.

Movies and television

The motion picture Nacho Libre, starring Jack Black as a priest-turned-luchador was inspired by the story of Father Sergio Gutiérrez Benítez, a real-life Catholic priest who wrestled as Fray Tormenta to make money for his church.[39] The documentary feature Lucha Mexico (2016) captured the lives of some of Mexico's well known wrestlers. The stars were Shocker, Blue Demon Jr., El Hijo del Perro Aguayo and Último Guerrero. Directed by Alex Hammond and Ian Markiewicz.[40] Rob Zombie's animated film The Haunted World of El Superbeasto stars a Mexican luchador named El Superbeasto.[41]

Television shows have also been inspired by Lucha Libre, especially animated series such as ¡Mucha Lucha!, Cartoon Network also produced an animated mini-series based on luchador El Santo.[42] The WB television series Angel episode entitled "The Cautionary Tale of Numero Cinco" told the story of a family of luchadores called "Los Hermanos Números" who also fought evil. Angel must help the remaining brother, Numero Cinco, defeat the Aztec warrior-demon that killed his four brothers.[43] In the British TV show Justin Lee Collins: The Wrestler, Colins competes as the rudo El Glorioso, or The Glorious One, against the exótico Cassandro in The Roundhouse, London, ultimately losing and being unmasked.[44] The book and television series The Strain by Guillermo del Toro and Chuck Hogan, features a retired luchador character called Angel de la Plata (The Silver Angel), played by Joaquin Cosio. In the storyline, Angel de la Plata (probably based on El Santo) was a major masked wrestling star in Mexico, appearing both in the ring and in a series of movies in which his character battled all manner of foes including vampires. A knee injury ended his career but he is called upon to use his fighting skills against a real-life vampire invasion of New York.[45] The Kids' WB animated program ¡Mucha Lucha! (2002–2005) depicts a whole town full of masked wrestlers who not only wrestle in matches, but also have regular jobs (such as owning and managing the town donut shop). Youngsters attend "The Foremost World Renowned International School Of Lucha" to get trained in the sport.

Video Games

The popular video game franchise Pokémon introduced the Fighting/Flying-type Pokémon Hawlucha, which is an hawk-like humanoid creature with elements of a lucha libre wrestler.

Internet Culture

Strong Bad of the Homestar Runner universe began as a parody of Lucha Libre. His head is designed after a mask.

Lucha libre inspirations

Nike has designed a line of lucha libre-inspired athletic shoes.[46] Coca-Cola developed a Blue Demon Full Throttle energy drink named after the luchador Blue Demon, Jr. who is also the spokesperson for the drink in Mexico.[47] Coca-Cola also introduced "Gladiator" in Mexico, an energy drink that sponsored CMLL events and that featured CMLL wrestlers such as Místico and Último Guerrero.[48]

See also

References

- "lucha libre – Definition of lucha libre in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries – English.

- Nickel, Robert (May 5, 2012). "Lucha Libre Facts". Artipot. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- Perasso, Valeria (December 10, 2011). "Lucha libre in the US: The wrestler who taunts Latino fans". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on March 27, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- Leavitt, Emily; Cortés, Zaira (February 21, 2014). "Masked Wrestlers Practice 'Lucha Libre' in the Bronx". Voices of NY. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- "Nombran a la lucha libre como Patrimonio cultural intangible de la CDMX". El Universal (in Spanish). July 21, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- Reseñas Deportivas (breve historia) Archived May 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (Spanish)

- El hijo del Santo (February 9, 2012). "Los personajes en la historia de la lucha libre mexicana (Spanish)". Record.com.mx. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "The History of Lucha Libre". Bongo.net. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "El Santo". Wrestling Museum. Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- "Lucha Legends: Gory Guerrero". Lethalwrestling.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "Blue Demon". Internationalhero.co.uk. April 24, 1922. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "Interview: Mil Mascaras and Satoru Sayama". Puroresudojo.com. August 3, 1995. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- Madigan, Dan (2007). "Okay... what is Lucha Libre?". Mondo Lucha Libre: the bizarre and honorable world of wild Mexican wrestling. HarperColins Publisher. pp. 29–40. ISBN 978-0-06-085583-3.

- "CANOE – SLAM! Sports – Wrestling – Lucha Libre 101". Slam.canoe.ca. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- Stas Bekman: stas (at) stason.org. "8.6. Lucha Libre confuses me, what are the rules?". Stason.org. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- Madigan, Dan (2007). "What is Lucha Libre". Mondo Lucha Libre: the bizarre & honorable world of wild Mexican wrestling. HarperColins Publisher. pp. 2–15. ISBN 978-0-06-085583-3.

- Brandt, Stacy (December 5, 2002). "Who Was That Masked Man?". The Daily Aztec. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009.

- "Xavier Garza". Archived from the original on July 11, 2011.

- "CANOE – SLAM! Sports – Wrestling – Viva la lucha libre!". Slam.canoe.ca. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- Heather Levi (2008). The World of Lucha Libre: Secrets, Revelations, and Mexican National Identity. Duke University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8223-4232-8. Archived from the original on June 29, 2016.

- Lourdes Grobet; Alfonso Morales; Gustavo Fuentes & Jose Manuel Aurrecoechea (2005). Lucha Libre: Masked Superstars of Mexican Wrestling. Trilce. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-933045-05-4.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved July 30, 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Arturo Montiel Rojas (August 30, 2001). "Reglamento de box y lucha libre profesional del estado de mexico" (PDF). Comisión de Box y Lucha Libre Mexico D.F. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 30, 2006. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

CAPITULO XXVI> DEL PESO DE LOS LUCHADORES

- "Wrestling Encyclopedia". Wrestling Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 12, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "Lucha Libre Moves". Surf-mexico.com. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- Bajko, Matthew S. (December 5, 2008). "Meet Lucha Libre's New Superstar: The Openly Gay 'Queen of the Ring'". Edgeboston.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- Madigan, Dan (2007). "A family affair". Mondo Lucha Libre: the bizarre & honorable world of wild Mexican wrestling. HarperColins Publisher. pp. 128–132. ISBN 978-0-06-085583-3.

- Among the new group of notable female luchadoras is El Gato de Plata (believed to be Ella Brown)CANOE – SLAM! Sports – Wrestling – LLF promoter loves his luchadoras Archived July 18, 2012, at Archive.today

- Madigan, Dan (2007). "You ain't seen nothing yet: the minis". Mondo Lucha Libre: the bizarre & honorable world of wild Mexican wrestling. HarperColins Publisher. pp. 209–212. ISBN 978-0-06-085583-3.

- Royal Duncan & Gary Will (2000). "Mexico: EMLL CMLL Midget (miniestrella) Title". Wrestling Title Histories. Archeus Communications. p. 396. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- "Los Angeles, CA (September 25, 2015) – Lucha Underground, the Lucha Libre wrestling franchise from United Artists Media Group and FactoryMade Ventures". Archived from the original on June 18, 2016.

- Johnson, Mike (February 7, 2016). "More on issues with Konnan, AAA and others in recent weeks". Pro Wrestling Insider. Archived from the original on February 9, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- Rocky Rolando. "Federacion Argentina De Catch". Facatch.com.ar. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- Crooker, Patricio. "The Wrestling cholitas of El Alto, Bolivia". American Ethnography Quasimonthly. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- Guillermoprieto, Alma (September 2008). "Bolivia's Wrestlers". National Geographic. Archived from the original on September 28, 2009. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 11, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Alberto Rodriguez 'Dos Caras Jr.'". Archived from the original on January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- Yoav (October 22, 2007). "ENCUESTA DE MITOFSKY REVELA QUE LA LUCHA NO ES EL SEGUNDO DEPORTE MÁS POPULAR EN MÉXICO". Súper Luchas (in Spanish). Archived from the original on August 4, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- Tuckman, Jo. "'I didn't want glory. I wanted money'". The Guardian. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- "Watch Masked Men Battle in 'Lucha Mexico' Trailer". Rolling Stone. July 6, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- "News: EXCL: Rob Zombie Interview". Shocktillyoudrop. Archived from the original on August 16, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- "Cartoon Network Announces Five New Series for 2007". Movieweb.com. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- M., Deborah (December 17, 2003), Jeff Bell – Cult Times Magazine Interview, Cult Times Magazine Special Edition

- Teeman, Tim (August 14, 2009). "Dolce Vito; Justin Lee Collins: Wrestler; How Clean Is Your House? – Last Night's TV". Home Arts & Entertainment TV & Radio. London: The Times. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- "Exclusive: FX's 'The Strain' Finds Its Vampire-Fighting Silver Angel". hitfix.com. January 13, 2015. Archived from the original on January 21, 2015.

- Halfhill, Matt (April 29, 2008). "Lucha Libre Air Force Ones". NiceKicks.com. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "Coca-Cola Introduces New Full Throttle Blue Demon Energy Drink". BevNET.com. November 9, 2006. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- Ocampo, Jorge (January 30, 2008). "Coca Cola México lanza Gladiator". Súper Luchas (in Spanish). Archived from the original on August 24, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

Notes

- Allatson, Paul (2007). Key Terms in Latino/a Cultural and Literary Studies. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405102506, ISBN 9781405102513. OCLC 71044272.

External links

Media related to Lucha libre at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lucha libre at Wikimedia Commons- Lucha Wiki

- Pro-Wrestling Title Histories of Mexico

- Title histories of Spain