Maternal deprivation

Maternal deprivation is a scientific term summarising the early work of psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby on the effects of separating infants and young children from their mother (or mother substitute)[1] although the effect of loss of the mother on the developing child had been considered earlier by Freud and other theorists. Bowlby's work on delinquent and affectionless children and the effects of hospital and institutional care led to his being commissioned to write the World Health Organization's report on the mental health of homeless children in post-war Europe whilst he was head of the Department for Children and Parents at the Tavistock Clinic in London after World War II.[2] The result was the monograph Maternal Care and Mental Health published in 1951, which sets out the maternal deprivation hypothesis.[3]

Bowlby drew together such empirical evidence as existed at the time from across Europe and the US, including Spitz (1946) and Goldfarb (1943, 1945). His main conclusions, that "the infant and young child should experience a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship with his mother (or permanent mother substitute) in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment" and that not to do so might have significant and irreversible mental health consequences, were both controversial and influential.[4] The monograph was published in 14 different languages and sold over 400,000 copies in the English version alone. Bowlby's work went beyond the suggestions of Otto Rank and Ian Suttie that mothering care was essential for development, and focused on the potential outcomes for children deprived of such care.

The 1951 WHO publication was highly influential in causing widespread changes in the practices and prevalence of institutional care for infants and children, and in changing practices relating to the stays of small children in hospitals so that parents were allowed more frequent and longer visits. Although the monograph was primarily concerned with the removal of children from their homes it was also used for political purposes to discourage women from working and leaving their children in daycare by governments concerned about maximising employment for returned and returning servicemen. The publication was also highly controversial with, amongst others, psychoanalysts, psychologists and learning theorists, and sparked significant debate and research on the issue of children's early relationships.

The limited empirical data and lack of comprehensive theory to account for the conclusions in Maternal Care and Mental Health led to the subsequent formulation of attachment theory by Bowlby.[5] Following the publication of Maternal Care and Mental Health Bowlby sought new understanding from such fields as evolutionary biology, ethology, developmental psychology, cognitive science and control systems theory and drew upon them to formulate the innovative proposition that the mechanisms underlying an infant's ties emerged as a result of evolutionary pressure.[6] Bowlby claimed to have made good the "deficiencies of the data and the lack of theory to link alleged cause and effect" in Maternal Care and Mental Health in his later work Attachment and Loss published between 1969 and 1980.[7]

Although the central tenet of maternal deprivation theory—that children's experiences of interpersonal relationships are crucial to their psychological development and that the formation of an ongoing relationship with the child is as important a part of parenting as the provision of experiences, discipline and child care—has become generally accepted, "maternal deprivation" as a discrete syndrome is not a concept that is much in current use other than in relation to severe deprivation as in "failure to thrive". In the area of early relationships it has largely been superseded by attachment theory and other theories relating to even earlier infant–parent interactions. As a concept, parental deficiencies are seen as a vulnerability factor for, rather than a direct cause of, later difficulties. In relation to institutional care there has been a great deal of subsequent research on the individual elements of privation, deprivation, understimulation and deficiencies that may arise from institutional care.

History

Scientific research has stressed the grief of mothers over deprivation of their children but little has been said historically about young children's loss of their mothers; this may have been because loss of the mother in infancy frequently meant death for a breast-fed infant. In the 19th century, French society bureaucratised a system in which infants were breast-fed at the homes of foster mothers, returning to the biological family after weaning, and no concern was evinced at the possible effect of this double separation on the child.[8]

Sigmund Freud may have been among the first to stress the potential effect of loss of the mother on the developing child, but his concern was less with the actual experience of maternal care than with the anxiety the child might feel about the loss of the nourishing breast.[9] As little of Freud's theory was based on actual observations of infants, little effort was made to consider the effects of real experiences of loss.

Following Freud's early speculations about infant experience with the mother, Otto Rank suggested a powerful role in personality development for birth trauma. Rank stressed the traumatic experience of birth as a separation from the mother, rather than birth as an uncomfortable physical event. Not long after Rank's introduction of this idea, Ian Suttie, a British physician whose early death limited his influence, suggested that the child's basic need is for mother-love, and his greatest anxiety is that such love will be lost.[9][10]

In the 1930s, David Levy noted a phenomenon he called "primary affect hunger" in children removed very early from their mothers and brought up in institutions and multiple foster homes. These children, though often pleasant on the surface, seemed indifferent underneath. He questioned whether there could be a "deficiency disease of the emotional life, comparable to a deficiency of vital nutritional elements within the developing organism".[11] A few psychiatrists, psychologists and paediatricians were also concerned by the high mortality rate in hospitals and institutions obsessed with sterility to the detriment of any human or nurturing contact with babies. One rare paediatrician went so far as to replace a sign saying "Wash your hands twice before entering this ward" with one saying "Do not enter this nursery without picking up a baby".[12]

In a series of studies published in the 1930s, psychologist Bill Goldfarb noted not only deficits in the ability to form relationships, but also in the IQ of institutionalised children as compared to a matched group in foster care.[12] In another study conducted in the 1930s, Harold Skeels, noting the decline in IQ in young orphanage children, removed toddlers from a sterile orphanage and gave them to "feeble-minded" institutionalised older girls to care for. The toddlers' IQ rose dramatically. Skeels study was attacked for lack of scientific rigour though he achieved belated recognition decades later.[13]

René Spitz, a psychoanalyst, undertook research in the 1930s and '40s on the effects of maternal deprivation and hospitalism. His investigation focused on infants who had experienced abrupt, long-term separation from the familiar caregiver, as, for instance, when the mother was sent to prison. These studies and conclusions were thus different from the investigations of institutional rearing. Spitz adopted the term anaclitic depression to describe the child's reaction of grief, anger, and apathy to partial emotional deprivation (the loss of a loved object) and proposed that when the love object is returned to the child within three to five months, recovery is prompt but after five months, they will show the symptoms of increasingly serious deterioration. He called this reaction to total deprivation "hospitalism". He was also one of the first to undertake direct observation of infants.[14][15] The conclusions were hotly disputed and there was no widespread acceptance.[16]

During the years of World War II, evacuated and orphaned children were the subjects of studies that outlined their reactions to separation, including the ability to cope by forming relationships with other children. Some of this material remained unpublished until the post-war period and only gradually contributed to understanding of young children's reactions to loss.[17][18]

Bowlby, who, unlike most psychoanalysts, had direct experience of working with deprived children through his work at the London Child Guidance Clinic, called for more investigation of children's early lives in a paper published in 1940. He proposed that two environmental factors were paramount in early childhood. The first was death of the mother, or prolonged separation from her. The second was the mother's emotional attitude towards her child.[19] This was followed by a study on forty–four juvenile thieves collected through the Clinic. There were many problematic parental behaviours in the samples but Bowlby was looking at one environmental factor that was easy to document, namely prolonged early separations of child and mother. Of the forty-four thieves, fourteen fell into the category which Bowlby characterised as being of an "affectionless character". Of these fourteen, twelve had suffered prolonged maternal separations as opposed to only two of the control group.[20]

An NIH study published in 2011 examined the impact of short, non-traumatic separation from the child's primary caregiver. The subjects were infants separated from their primary caregiver for at least a week. Controlling for various factors including income, stability, and parenting style, the study found increased aggressiveness at ages 3 and 5 in separated infants, but it did not find other cognitive impairment. Most infants in the study stayed with close relatives or the other parent, often in the infant's home, suggesting that even in ideal circumstances, maternal separation can have lasting detrimental impact on infant development. [21]

Maternal Care and Mental Health

Bowlby's work on delinquent and affectionless children and the effects of hospital and institutional care lead to his being commissioned to write the World Health Organization's report on the mental health of homeless children in post-war Europe whilst he was head of the Department for Children and Parents at the Tavistock Clinic in London after World War II.[2] Bowlby travelled on the Continent and in America, communicating with social workers, paediatricians and child psychiatrists including those who had already published literature on the issue. These authors were mainly unaware of each other's work, and Bowlby was able to draw together the findings and highlight the similarities described, despite the variety of methods used, ranging from direct observation to retrospective analysis to comparison groups. In addition, there was work from England undertaken by Dorothy Burlingham and Anna Freud on children separated from their families due to wartime disruption, and Bowlby's own work.[22] The result was the monograph Maternal Care and Mental Health published in 1951, which sets out the maternal deprivation hypothesis.[3] The WHO report was followed by the publication of an abridged version for public consumption called Child Care and the Growth of Love. This book sold over half a million copies worldwide. Bowlby tackled not only institutional and hospital care, but also policies of removing children from "unwed mothers" and untidy and physically neglected homes, and lack of support for families in difficulties. In a range of areas Bowlby cited the lack of adequate research and suggested the direction this could take.[23]

Principal concepts of Bowlby's theory

The quality of parental care was considered by Bowlby to be of vital importance to the child's development and future mental health. It was believed to be essential that the infant and young child should experience a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship with his mother (or permanent mother substitute) in which both found satisfaction and enjoyment. Given this relationship, emotions of guilt and anxiety (characteristics of mental illness when in excess) would develop in an organised and moderate way. Naturally extreme emotions would be moderated and become amenable to the control of the child's developing personality. He stated, "It is this complex rich and rewarding relationship with the mother in the early years, varied in countless ways by relations with the father and with siblings, that child psychiatrists and many others now believe to underlie the development of character and mental health."[4]

The state of affairs in which the child did not have this relationship he termed "maternal deprivation". This term covered a range from almost complete deprivation, not uncommon in institutions, residential nurseries and hospitals, to partial deprivation where the mother, or mother substitute, was unable to give the loving care a small child needs, to mild deprivation where the child was removed from the mother's care but was looked after by someone familiar whom he trusted.[24] Complete or almost complete deprivation could "entirely cripple the capacity to make relationships". Partial deprivation could result in acute anxiety, depression, neediness and powerful emotions which the child could not regulate. The end product of such psychic disturbance could be neurosis and instability of character.[24] However, the main focus of the monograph was on the more extreme forms of deprivation. The focus was the child's developing relationships with his mother and father and disturbed parent–child relationships in the context of almost complete deprivation rather than the earlier concept of the "broken home" as such.[3]

In terms of social policy, Bowlby advised that parents should be supported by society as parents are dependent on a greater society for economic provision and "if a community values its children it must cherish its parents". Also "husbandless" mothers of children under 3 should be supported to care for the child at home rather than the child be left in inadequate care whilst the mother sought work. (It was assumed the mother of the illegitimate child would usually be left with the child). Fathers left with infants or small children on their hands without the mother should be provided with "housekeepers" so that the children could remain at home.[25] Other proposals included the proper payment of foster homes and careful selection of foster carers,[26] and frank, informative discussions with children about their parents and why they ended up in care and how they felt about it rather than the "least said, soonest mended" approach. The point that children were loyal to and loved even the worst of parents, and needed to have that fact understood non-judgementally, was strongly made.[27]

On the issue of removal of children from their homes, Bowlby emphasised the strength of the tie that children feel towards their parents and discussed the reason why, as he put it, "children thrive better in bad homes than in good institutions". He was strongly in favour of support being provided to parents and extended families to improve the situation and provide care within the family rather than removal if possible.[28]

"Maternal"

Bowlby used the phrase "mother (or permanent mother substitute)".[4] As it is commonly used, the term maternal deprivation is ambiguous as it is unclear whether the deprivation is that of the biological mother, of an adoptive or foster mother, a consistent caregiving adult of any gender or relationship to the child, of an emotional relationship, or of the experience of the type of care called "mothering" in many cultures. Questions about the exact meaning of this term are by no means new, as the following statement by Mary Ainsworth in 1962 indicates: "Although in the early months of life it is the mother who almost invariably interacts most with the child ... the role of other figures, especially the father, is acknowledged to be significant ... [P]aternal deprivation ... has received scant attention ... [In the case of] institutionalization ... the term 'parental deprivation' would have been more accurate, for the child has been ... deprived of interaction with a father-figure as well as a mother-figure ... [It may be better to] discourage the use of [the term 'deprivation'] and encourage the substitution of the terms 'insufficiency', 'discontinuity', and 'distortion' instead."[29] Ainsworth implies, neither the word "maternal" nor the word "deprivation" seems to be a literally correct definition of the phenomenon under consideration.

A contemporary of Ainsworth spoke of "the mother, a term by which we mean both the child's actual mother and/or any other person of either sex who may take the place of the child's physical mother during a significant period of time".[30] However, another contemporary referred to "the quasi-mystical union of mother and child, of the dynamic union that mother and child represent".[31]

Influence on institutionalised care

The practical effects of the publication of Maternal Care and Mental Health were described in the preface to the WHO 1962 publication Deprivation of Maternal Care: A Reassessment of its Effects as "almost wholly beneficial" with reference to widespread changes in the institutional care of children.[32]

The practice of allowing parents frequent visiting to hospitalised children became the norm and there was a move towards placing homeless children with foster carers, rather than in institutions, and a move towards the professionalisation of alternative carers. In hospitals, the change was given added impetus by the work of social worker and psychoanalyst James Robertson who filmed the distressing effects of separation on children in hospital and collaborated with Bowlby in making the 1952 documentary film A Two-Year Old Goes to the Hospital.[33]

According to Michael Rutter, the importance of Bowlby's initial writings on "maternal deprivation" lay in his emphasis that children's experiences of interpersonal relationships were crucial to their psychological development and that the formation of an ongoing relationship with the child was as important a part of parenting as the provision of experiences, discipline and child care. Although this view was rejected by many at the time, the argument focussed attention on the need to consider parenting in terms of consistency of caregivers over time and parental sensitivity to children's individuality and it is now generally accepted.[34] Bowlby's theory sparked considerable interest and controversy in the nature of early relationships and gave a strong impetus to what Mary Ainsworth described as a "great body of research" in what was perceived as an extremely difficult and complex area.[32]

Psychoanalysis

Bowlby departed from psychoanalytical theory which saw the gratification of sensory needs as the basis for the relationship between infant and mother.[2] Food was seen as the primary drive and the relationship, or "dependency" was secondary.[5] He had already found himself in conflict with dominant Kleinian theories that children's emotional problems are almost entirely due to fantasies generated from internal conflict between aggressive and libidinal drives, rather than to events in the external world. (His breach with the psychoanalysts only became total and irreparable after his later development of attachment theory incorporating ethological and evolutionary principles, when he was effectively ostracised). Bowlby also broke with social learning theory's view of dependency and reinforcement. Bowlby proposed instead that to thrive emotionally, children needed a close and continuous caregiving relationship.[2]

Bowlby later stated that he had concluded that, contrary to the focus of psychoanalysts on the internal fantasy world of the child, the important area to study was how a child was actually treated by his parents in real life and in particular the interaction between them. He chose the actual removal of children from the home at this particular time because it was a specific event, the effects of which could be studied, and because he believed it could have serious effects on a child's development and because it was preventable. In addition, views that he had already expressed about the importance of a child's real life experiences and relationship with carers had been met by "sheer incredulity" by colleagues before World War II. This led him to see that far more systematic knowledge was required of the effects on a child of early experiences. Bowlby and his colleagues were pioneers of the view that studies involving direct observation of infants and children were not merely of interest but were essential to the advancement of science in this area.[35]

Animal studies

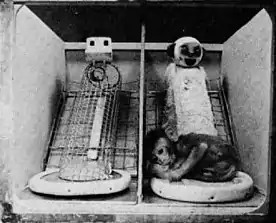

Researchers have for years studied depression, alcoholism, aggression, maternal-infant bonding and other conditions and phenomena in nonhuman primates and other laboratory animals using an experimental maternal deprivation paradigm.[36] Most influentially, Harry Harlow would, in the mid-1950s, begin raising infant monkeys in his University of Wisconsin–Madison laboratory in total or partial isolation and with inanimate surrogate mothers in an attempt to study maternal-infant bonding as well as various states of mental illness.[37]

In Harlow's laboratory, infant rhesus monkeys were immediately removed from their mothers and placed with cloth or wire surrogate mothers, sometimes called "iron maidens" by the researchers.[37][38] Harlow found that the infants would become attached to their inanimate mothers—both those made of wire and those covered with cloth—and when removed from them they would "screech in terror". Harlow and his colleagues would later develop "evil artificial mothers" meant to "impart fear and insecurity to infant monkeys"—including one designed with brass spikes—but contrary to the researcher's hypothesis, these animals too demonstrated an attachment to their surrogates.[38]

Subsequent experiments would study the effects of total and partial isolation on the animals' mental health and interpersonal bonding using a stainless steel vertical chamber designed by Harlow, named the "pit of despair", which was found to produce "profound and prolonged depression" in monkeys. Similarly, Harlow found that extended isolation in bare wire cages left monkeys with "profound behavioral abnormalities" including "self-clutching and rocking" and later "apathy and indifference to external stimulation". Harlow likened this behavior to catatonic schizophrenia.[38]

Later experiments were devised to test the mother-child bond with mothers who had themselves been reared in isolation as infants. This early deprivation was found to have retarded the mothers' emotional development and her ability to engage in intercourse and in turn become pregnant. In response, Harlow and his colleagues created an apparatus to impregnate these mothers they named a "rape rack". Harlow found that once these monkeys gave birth, they cared little for their offspring writing, "these monkey mothers that had never experienced love of any kind were devoid of love for their infants". While some mothers simply ignored their children, Harlow characterized others as "evil" and abusive and in some instances reported them "crushing the infant's face to the floor, chewing off the infant's feet and fingers, and in one case... putting the infant's head in her mouth and crushing it like an eggshell".[38]

Harlow's experiments have been heralded as revolutionary and also robustly criticized as scientifically invalid and sadistically cruel.[36][37] Writing on the researcher's legacy, John Gluck, a former student of Harlow's opined, "On the one hand, his work on monkey cognition and social development fostered a view of the animals as having rich subjective lives filled with intention and emotion. On the other, he has been criticized for the conduct of research that seemed to ignore the ethical implantations of his own discoveries."[37]

Maternal deprivation experiments on nonhuman primates have continued into the 21st century and remain controversial. Stephen Suomi, an early collaborator of Harlow, has continued to conduct maternal deprivation experiments on rhesus monkeys in his NIH laboratory and has been vigorously criticized by PETA, Members of Congress and others.[39][40][41]

Controversy, misinterpretation and criticism

Aside from his profound differences with psychoanalytic ideas, the theoretical basis of Bowlby's monograph was controversial in a number of ways. Some profoundly disagreed with the necessity for maternal (or equivalent) love in order to function normally,[42] or that the formation of an ongoing relationship with a child was an important part of parenting.[34] The idea that early experiences have serious consequences for intellectual and psychosocial development was controversial in itself.[43] Others questioned the extent to which his hypothesis was supported by the evidence. There was criticism of the confusion of the effects of privation (no primary attachment figure) and deprivation (loss of the primary attachment figure) and in particular, of the failure to distinguish between the effects of the lack of a primary attachment figure and the other forms of deprivation and understimulation that might affect children in institutions.[44]

It was also pointed out that there was no explanation of how experiences subsumed under the broad heading of "maternal deprivation" could have effects on personality development of the kinds claimed. Bowlby explained in his 1988 work that the data were not at the time "accommodated by any theory then current and in the brief time of my employment by the World Health Organization there was no possibility of developing a new one". He then goes on to describe the subsequent development of attachment theory.[5]

In addition to criticism, his ideas were often oversimplified, misrepresented, distorted or exaggerated for various purposes. This heightened the controversy.[43] In 1962, the WHO published Deprivation of Maternal Care: A Reassessment of its Effects to which Mary Ainsworth, Bowlby's close colleague, contributed with his approval, to present the recent research and developments and to address misapprehensions.[32]

Bowlby's work was misinterpreted to mean that any separation from the natural mother, any experience of institutional care or a multiplicity of "mothers" necessarily resulted in severe emotional deprivation and sometimes, that all children undergoing such experiences would develop into "affectionless children". As a consequence it was claimed that only 24-hour care by the same person (the mother) was good enough, day care and nurseries were not good enough and mothers should not go out to work. The WHO advised that day nurseries and creches could have a serious and permanent deleterious effect.[44] Such strictures suited the policies of governments concerned about finding employment for returned and returning servicemen after World War II.[45] In fact, although Bowlby was of the view that proper care could not be provided "by roster", he was also of the view that babies should be accustomed to regular periods of care by another and that the key to alternative care for working mothers was that it should be regular and continuous.[44] He addressed this point in a 1958 publication called Can I Leave My Baby?. Ainsworth in the WHO 1962 publication also attempted to address this misapprehension by pointing out that the requirement for continuity of care did not imply an exclusive mother–child pair relationship.[29]

Bowlby's quotable remark, that children thrived better in bad homes than in good institutions,[46] was often taken to extremes leading to reluctance on the part of Children's Officers (the equivalent of child care social workers) to remove children from homes however neglectful and inadequate. In fact, although Bowlby mentioned briefly the issue of "partial deprivation" within the family, this was not fully investigated in his monograph as the main focus was on the risks of complete or almost complete deprivation.[47]

Michael Rutter made a significant contribution to the controversial issue of Bowlby's maternal deprivation hypothesis. His 1981 monograph and other papers comprise the definitive empirical evaluation and update of Bowlby's early work on maternal deprivation.[44][47][48] He amassed further evidence, addressed the many different underlying social and psychological mechanisms and showed that Bowlby was only partially right and often for the wrong reasons. Rutter highlighted the other forms of deprivation found in institutional care and the complexity of separation distress; and suggested that anti-social behaviour was not linked to maternal deprivation as such but to family discord. The importance of these refinements of the maternal deprivation hypothesis was to reposition it as a "vulnerability factor" rather than a causative agent, with a number of varied influences determining which path a child would take.[49]

Rutter has more recently advised attention to the complexity of development and the roles of genetic as well as experiential factors, noting that separation is only one of many risk factors related to poor cognitive and emotional development.[50]

Fathers

In accordance with the prevailing social realities of his time, namely the assumption that the daily care of infants and small children was undertaken by women and in particular, mothers, Bowlby referred primarily to mothers and "maternal" deprivation, although the words "parents" and "parental" are also used.[2] Fathers are mentioned only in the context of the practical and emotional support they provide for the mother but the monograph contains no specific exploration of the father's role. Nor is there any discussion as to whether the maternal role had, of necessity, to be filled by women as such. Bowlby's work was misinterpreted by some to mean natural mothers only.[51]

The 1962 WHO publication contains a chapter on the effect of "paternal deprivation", there having by 1962 been some limited research on the issue which illustrated the importance of the father's relationship with his children.[51] The hope was expressed by Ainsworth that in the future there would be more such research and indeed her early research, which contributed significantly to attachment theory, covered infants relationships with all family members. It was also stated that in relation to institutional care, "parental deprivation" would have been more accurate, although Ainsworth preferred the terms "insufficiency", "discontinuity" and "distortion" to either.[29]

Michael Rutter in Maternal Deprivation Reassessed (1972), described by New Society as a "classic in the field of child care", argued that research showed that it did not matter which parent the child got on well with as long as he got on well with one of them, that both parents influence their child's development and that which parent is more important varies with age, sex and temperamental development. He concluded, "For some aspects of development the same-sexed parent seems to have a special role, for some the person who plays and talks most with the child and for others the person who feeds the child. The father, the mother, brother and sisters, friends, school-teachers and others all affect development, but their influences and importance differ for different aspects of development. A less exclusive focus on the mother is required. Children also have fathers!"[47]

Within attachment theory, Bowlby, in Attachment and Loss, volume one of Attachment (1969), makes it quite clear that infants become attached to carers who are sensitive and responsive in their social interactions with them and that this does not have to be the mother or indeed a female. As a matter of social reality mothers are more often the primary carers of children and therefore are more likely to be the primary attachment figure, but the process of attachment applies to any carer and infants develop a number of attachments according to who relates to them and the intensity of the engagement.[52] However, attachment theory relates to the development of attachment behaviours and relationships after about 7 months of age and there are other theories and research relating to earlier carer–infant interactions.

Schaffer in Social Development (1996) suggests that the father–child relationship is primarily a cultural construction shaped by the requirements of each society. In societies where the care of infants has been assigned to boys rather than girls, no difference in nurturing capacity was found.[53][54] Other studies, however, point in the opposite direction.[55]

Feminist criticism

There were three broad criticisms aimed at the idea of maternal deprivation from feminist critics.[56] The first was that Bowlby overstated his case. The studies on which he based his conclusions involved almost complete lack of maternal care and it was unwarranted to generalise from this view that any separation in the first three years of life would be damaging. Subsequent research showed good quality care for part of the day to be harmless. The idea of exclusive care or exclusive attachment to a preferred figure, rather than a hierarchy (subsequently thought to be the case within developments of attachment theory) had not been borne out by research and this view placed too high an emotional burden on the mother. Secondly, they criticised Bowlby's historical perspective and saw his views as part of the idealisation of motherhood and family life after World War II. Certainly his hypothesis was used by governments to close down much needed residential nurseries although governments did not seem so keen to pay mothers to care for their children at home as advocated by Bowlby. Thirdly, feminists objected to the idea of anatomy as destiny and concepts of "naturalness" derived from ethnocentric observations. They argued that anthropology showed that it is normal for childcare to be shared by a stable group of adults of which maternal care is an important but not exclusive part.[56]

Today

Whilst Bowlby's early writings on maternal deprivation may be seen as part of the background to the later development of attachment theory, there are many significant differences between the two. At the time of the 1951 publication, there was little research in this area and no comprehensive theory on the development of early relationships.[5] Aside from its central proposition of the importance of an early, continuous and sensitive relationship, the monograph concentrates mostly on social policy. For his subsequent development of attachment theory, Bowlby drew on concepts from ethology, cybernetics, information processing, developmental psychology and psychoanalysis. The first early formal statements of attachment theory were presented in three papers in 1958, 1959 and 1960. His major work Attachment was published in three volumes between 1969 and 1980. Attachment theory revolutionised thinking on the nature of early attachments and extensive research continues to be undertaken.[6]

According to Zeanah, "ethological attachment theory, as outlined by John Bowlby ... 1969 to 1980 ... has provided one of the most important frameworks for understanding crucial risk and protective factors in social and emotional development in the first 3 years of life. Bowlby's (1951) monograph, Maternal Care and Mental Health, reviewed the world literature on maternal deprivation and suggested that emotionally available caregiving was crucial for infant development and mental health."[57] Beyond that broad statement, which is now generally accepted, little remains of the underlying detail of Bowlby's theory of maternal deprivation that has not been either discredited or superseded by attachment theory and other child development theories and research, except in the area of extreme deprivation.

The opening of East European orphanages in the early 1990s following the end of the Cold War provided substantial opportunities for research on attachment and other aspects of institutional rearing, however such research rarely mentions "maternal deprivation" other than in a historical context. Maternal deprivation as a discrete syndrome is a concept that is rarely used other than in connection with extreme deprivation and failure to thrive. Rather there is consideration of a range of different lacks and deficiencies in different forms of care, or lack of care, of which attachment is only one aspect, as well as consideration of constitutional and genetic factors in determining developmental outcome.[50] Subsequent studies have however confirmed Bowlby's concept of "cycles of disadvantage" although not all children from unhappy homes reproduce the deficiencies in their own experience.[58] Rather, it is now conceptualised as a series of pathways through childhood and a number of varied influences will determine which path a particular child takes.[44]

The concept outside mainstream psychology

The idea that separation from the female caregiver has profound effects is one with considerable resonance outside the conventional study of child development. In United States law, the "tender years" doctrine was long applied when custody of infants and toddlers was preferentially given to mothers. Over the last decade or so, some decisions appear to have been derived from the "tender years" concept, but others involve the contrary assumption that a 2-year-old is too young to have developed a relationship with either parent.[59]

Concern with the harm of separation from the mother is characteristic of the belief systems behind some complementary and alternative (CAM) psychotherapies. Such belief systems are concerned not only with the effect of the young child's separation from the care of the mother, but with an emotional attachment between mother and child which advocates of these systems believe to develop prenatally. Such attachment is said to lead to emotional trauma if the child is separated from the birth mother and adopted, even if this occurs on the day of birth and even if the adoptive family provides all possible love and care. These beliefs were at one time in existence among psychologists of psychoanalytic background.[9][60] Today, however, beliefs in prenatal communication between mothers and infants are largely confined to unconventional thinkers such as William Emerson.[61]

Belief in prenatal fetal awareness, mental communication between mother and unborn child, and emotional attachment of child to mother as a prenatal phenomenon, are concepts that connect easily to the unfounded assumption that all adopted children suffer emotional disorders. These beliefs are also congruent with CAM psychotherapies such as attachment therapy (not based on attachment theory), which purport to bring about age regression and to recapitulate early development to produce a better outcome.[62]

See also

References

- Holmes 1993, p. 221

- Bretherton, I. (1992). "The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth". Developmental Psychology. 28 (5): 759–775. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759. S2CID 3964292.

- Bowlby, John (1995) [1951]. Maternal Care and Mental Health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. Master Work Series. 2 (Softcover ed.). Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson. pp. 355–533. ISBN 978-1-56821-757-4. PMC 2554008. PMID 14821768.

- Bowlby 1995, p. 11

- Bowlby 1988, p. 24

- Cassidy, J. (1999). "The Nature of the Child's Ties". In Cassidy, J.; Shaver, P.R. (eds.). Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications. Guilford press. ISBN 978-1-57230-826-8.

- Bowlby, J. (1986). "Maternal Care and Mental Health" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. Citation Classic. 3 (3): 355–533. PMC 2554008. PMID 14821768.

- Fildes, V. (1988). Wet Nursing. New York: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-15831-8.

- Brown, J.A.C. (1961). Freud and the Post-Freudians. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-020522-0.

- Suttie, I. (1935). The Origins of Love and Hate. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-415-21042-3.

- Karen 1998, pp. 13–17

- Karen 1998, pp. 20–21

- Karen 1998, pp. 18–22

- Spitz, R. (1945). "Hospitalism: An inquiry into the genesis of psychiatric conditions in early childhood". Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 1: 53–74. doi:10.1080/00797308.1945.11823126. PMID 21004303.

- Spitz, R. (1950). "Relevance of direct infant observation". Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 5: 66–73. doi:10.1080/00797308.1950.11822885.

- Karen 1998, p. 25

- Freud, A. & Burlingham, D.T. (1943). War and Children. New York: Medical War Books. ISBN 978-0-8371-6942-2.

- Freud, A. & Burlingham, D.T. (1939–1945). Infants Without Families and Reports on the Hampstead Nurseries. The Writings of Anna Freud. 3. New York: International Universities Press.

- Karen J. pp. 26–29

- Bowlby J (1944). "Forty-four juvenile thieves: Their characters and home life". International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 25 (19–52): 107–27.

sometimes referred to by Bowlby's colleagues as "Ali Bowlby and the Forty Thieves"

- Howard, Kimberly; Martin, Anne; Berlin, Lisa J.; Brooks-Gunn, Jeanne (1 January 2011). "Early Mother-Child Separation, Parenting, and Child Well-Being in Early Head Start Families". Attachment & Human Development. 13 (1): 5–26. doi:10.1080/14616734.2010.488119. PMC 3115616. PMID 21240692.

- Karen 1998, pp. 59–62

- Karen 1998, pp. 62–66

- Bowlby 1995, pp. 11–12

- Bowlby 1995, pp. 84–90

- Bowlby 1995, pp. 117–122

- Bowlby 1995, pp. 124–126

- Bowlby 1995, pp. 67–92

- Ainsworth, M.D. (1962). "The Effects of Maternal Deprivation: A Review of Findings and Controversy in the Context of Research Strategy". Deprivation of Maternal Care: A Reassessment of its Effects. Public Health Papers. 14. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241300148.

- Spitz, R.A. (1949). "Autoerotism". Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 3: 85–120. doi:10.1080/00797308.1947.11823082.

- Rank, B. (1949). "Aggression". Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 3: 43–48. doi:10.1080/00797308.1947.11823078.

- Ainsworth, Mary D. Salter; Andry, R.G.; Harlow, Robert G.; Lebovici, S.; Mead, Margaret; Prugh, Dane G.; Wootton, Barbara; et al. (1962). Deprivation of Maternal Care: A Reassessment of its Effects. 14. Geneva: World Health Organization, Public Health Papers. ISBN 9789241300148.

- Schwartz, J. (1999). Cassandra's Daughter: A History of Psychoanalysis. Viking/Allen Lane. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-670-88623-4.

- Rutter, M. (May 1995). "Clinical implications of attachment concepts: retrospect and prospect". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 36 (4): 549–71. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb02314.x. PMID 7650083.

- Bowlby 1988, pp. 43–45

- "A Critique of Maternal Deprivation Experiments on Primates". Modern Research Modernization Committee. Modern Research Modernization Committee. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Gluck, John (1997). "Harry F. Harlow and animal research: reflection on the ethical paradox". Ethics & Behavior. 7 (2): 149–161. doi:10.1207/s15327019eb0702_6. PMID 11655129. S2CID 42157109.

- Harlow, H.F.; Harlow, M.K.; Suomi, S.J (1971). "From thought to therapy: Lessons from a primate laboratory". American Scientist. 59 (5): 538–549. Bibcode:1971AmSci..59..538H. PMID 5004085.

- Grimm, David (29 December 2014). "Members of Congress request investigation into U.S. monkey lab". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Science. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Firger, Jessica (8 September 2014). "Questions raised about mental health studies on baby monkeys at NIH labs". CBS News. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- King, Barbara (19 May 2015). "Cruel Experiments on Infant Monkeys Still Happen All the Time--That Needs to Stop". Scientific American. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Wootton B. (1962). "A Social Scientist's Approach to Maternal Deprivation". Deprivation of Maternal Care: A Reassessment of its Effects. Public Health Papers. 14. Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 255–266. ISBN 9789241300148.

- Karen 1998, p. 65

- Rutter M. (1981). Maternal Deprivation Reassessed (2nd ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-022700-0.

- Holmes 1993, pp. 45–46

- Bowlby 1995, p. 68

- Rutter M. (1972). Maternal Deprivation Reassessed. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-080561-1.

- Rutter 1979.

- Holmes 1993, pp. 49–51

- Rutter M. (2002). "Nature, nurture, and development: from evangelism through science toward policy and practice". Child Dev. 73 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00388. PMID 14717240. S2CID 10334844.

- Andry R.G. (1962). "Paternal and Maternal Roles and Delinquency". Deprivation of Maternal Care: A Reassessment of its Effects. Public Health Papers. 14. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241300148.

- Bowlby J. (1982) [1969]. Attachment: Attachment and Loss. 1. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-7471-3.

- Schaffer, H.R. (1996). Social Development: an introduction. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-18574-1.

- Field, T. (1978). "Interaction behaviours of primary versus secondary caretaker fathers". Developmental Psychology. 14 (2): 183–184. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.14.2.183.

- Daubney, Martin (22 June 2016). "How 'dad deprivation' could be eroding modern society". The Telegraph – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- Holmes 1993, pp. 45–48

- Zeanah, C.H. (February 1996). "Beyond insecurity: a reconceptualization of attachment disorders of infancy". J Consult Clin Psychol. 64 (1): 42–52. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.64.1.42. PMID 8907083.

- Holmes 1993, p. 51

- Mercer, J. (2006). Understanding Attachment: Parenting, Child Care, and Emotional Development. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98217-1.

- Freud, W.E. (1973). "Prenatal attachment and bonding". In Greenspan, S.I.; Pollock, G.H. (eds.). The Course of Life, Vol. I, Infancy. Nadison, CT: International Universities Press.

- Emerson, W.R. (1996). "The vulnerable pre-nate". Pre- and Perinatal Psychology Journal. 10 (3): 125–142.

- Mercer, J.; Sarner, L.; Rosa, L. (2003). Attachment therapy On Trial: The Torture and Death of Candace Newmaker. Child Psychology & Mental Health. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-97675-0.

Bibliography

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-00640-8.

- Holmes, J. (1993). John Bowlby & Attachment Theory. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-07730-9.

- Karen, R. (1998). Becoming Attached: First Relationships and How They Shape Our Capacity to Love. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511501-7.

External links

- Bowlby, John (1951). "Maternal Care and Mental Health". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 3 (3): 355–533. PMC 2554008. PMID 14821768.

- Bowlby, John (1952). Maternal Care and Mental Health (Report). World Health Organization Monograph Series. 2 (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Spitz, René (1957). Psychogenic Disease in Infancy (film) – via Internet Archive.