Military history of the Northern and Southern dynasties

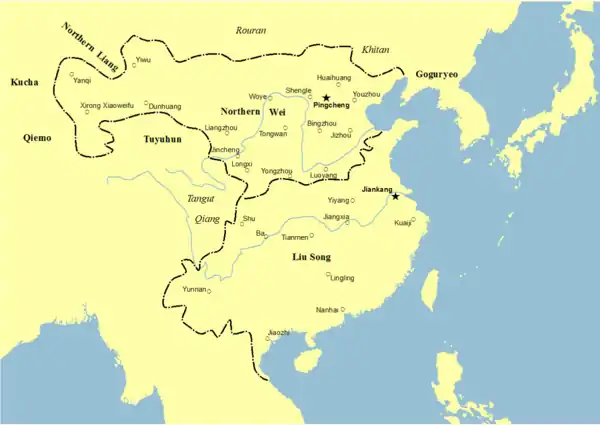

The military history of the Northern and Southern dynasties encompasses the period of Chinese military activity from 420 to 589. Officially starting with Liu Yu's usurpation of the Jin throne and creation of his Liu Song dynasty in 420, it ended in 589 with the Sui dynasty's conquest of Chen dynasty and reunification of China. The first of the Northern dynasties did not however begin in 420, but in 386 with the creation of Northern Wei. Thus there is some unofficial overlap with the era of the Sixteen Kingdoms.

Organization

South

During the Eastern Jin period, the army relied on a system of hereditary military households for recruitment. However, having lost the resources of the north, the Eastern Jin army attempted to bolster the number of military families in the south by incorporating convicts, vagrants, and aboriginals. This resulted in a general decline of social status and morale in the military. By the end of the dynasty, military men were regarded little better than government slaves. Terms of service were exceedingly harsh. One in three men from a military family was called upon for a term of service lasting from the age of 15 to their 60s. Essentially their entire life. Those who suffered debilitating injuries had to find a replacement from their family to procure release. Desertion was rampant and exit from the military household system a much sought after reward. By the sixth century the system of hereditary military households had collapsed.[1]

During the Liu Song dynasty, voluntary recruits began to supplant the defunct military caste system. Many of these soldiers were former members of the previous system who had been freed, and had chosen to re-enlist for better terms, or because they could find no better employment. In practice, many of the military communities which had sprung up during the era of hereditary troops stayed together, and provided the basis for recruitment for the next dynasty.[2] By the Liang and Chen dynasties, voluntary recruits had become the dominant component of the military.[2]

Commoners were sometimes called up during times of special need, however their service was generally relegated to labor or logistical duties. Military commanders of the time had little faith in their fighting ability.[2]

North

After Northern Wei shifted its capital to Luoyang, the lower class Xianbei were registered as "garrison households". These functioned similarly to the southern hereditary military households and were used for frontier garrison posts. They were excluded from the formal ranking system.[3] After the collapse of Northern Wei, the Eastern Wei regime absorbed the greater portion of North Asian warriors and preferred to deploy them over the Han Chinese. The Western regime lacked the manpower to forego Han Chinese recruits and made significant use of them in their campaigns.[4]

Fubing

In 550, Western Wei created the Twenty-four Armies, the predecessor of the fubing system, which formed the basis of military recruitment in the Sui dynasty and early Tang dynasty.[5]

The primary significance of the Twenty-four Armies was that Yuwen Tai had managed to bolster his forces to a size far beyond what he originally started with. From 50,000 men in 550, the Twenty-four Armies had doubled in size by 570. It's not certain how this happened and the specifics are still a source of contention. The general view is that to create the Twenty-four Armies, the Western Wei government implemented a system of mass recruitment. However, unlike the conscription of the Han dynasty, this time the government provided new incentives by removing the names of recruits from the household registers. This meant that they were effectively free from normal tax and labor obligations. It was said that "after this half the Chinese became soldiers".[6]

The utilization of Chinese troops eventually led to the triumph of Northern Zhou over Southern Qi. Despite having a larger population base, the eastern Xianbei elite hailed from the northern garrisons which opposed sinicizing policies at the capital. They treated the Chinese with disdain and distrust, refusing to incorporate them into their military structure. The Chinese population reciprocated this sentiment and did little to help their overlords in times of need. In the west, the Xianbei had no choice but to rely upon not just the Chinese, but also the Qiang, for they lacked the numbers to stand up to their eastern counterpart. The result was a new hybridized northwestern aristocracy of Xianbei, Chinese, and Qiang descent that gave birth to the Sui and Tang dynasties.[7]

Equipment

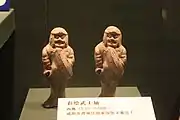

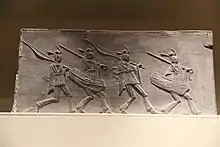

During the Northern and Southern dynasties period (420-589), a style of armour called "cord and plaque" became popular, as did shields and long swords. "Cord and plaque" armour consisted of double breast plates in the front and back held in position by two shoulder straps and waist cords, in conjunction with the usual lamellar armour. "Cord and plaque" wearing figurines are also often depicted holding an oval or rectangular shield and a long sword.[8] Types of armour had also apparently become distinct enough for there to be separate categories for light and heavy armour.[9]

In the 6th century, Qimu Huaiwen introduced to Northern Qi the process of 'co-fusion' steelmaking, which used metals of different carbon contents to create steel. Apparently sabers made using this method were capable of penetrating 30 armour lamellae. It's not clear if the armour was of iron or leather.

Huaiwen made sabres [dao 刀] of 'overnight iron' [su tie 宿鐵]. His method was to anneal [shao 燒] powdered cast iron [sheng tie jing 生鐵精] with layers of soft [iron] blanks [ding 鋌, presumably thin plates]. After several days the result is steel [gang 剛]. Soft iron was used for the spine of the sabre, He washed it in the urine of the Five Sacrificial Animals and quench-hardened it in the fat of the Five Sacrificial Animals: [Such a sabre] could penetrate thirty armour lamellae [zha 札]. The 'overnight soft blanks' [Su rou ting 宿柔鋌] cast today [in the Sui period?] by the metallurgists of Xiangguo (襄國) represent a vestige of [Qiwu Huaiwen's] technique. The sabres which they make are still extremely sharp, but they cannot penetrate thirty lamellae.[10]

The Northern Wei employed the "iron-clad" Erzhu tribe who fought as armoured cavalry.[8]

Soldiers of the Northern dynasties

Soldiers of the Northern dynasties Soldiers of the Northern dynasties

Soldiers of the Northern dynasties.jpg.webp) Northern dynasties shieldbearer

Northern dynasties shieldbearer A soldier of the Northern dynasties

A soldier of the Northern dynasties Northern Qi soldier

Northern Qi soldier Northern Qi soldier

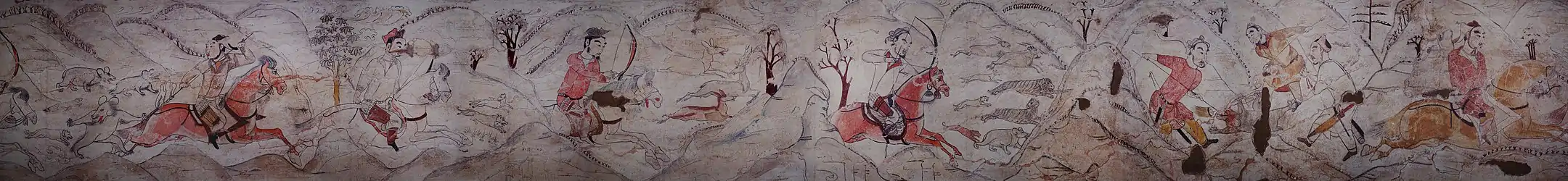

Northern Qi soldier Northern Wei cavalry

Northern Wei cavalry

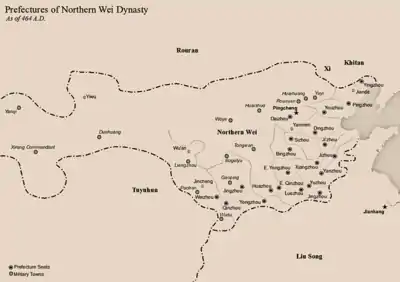

Northern Wei (386–535)

End of the Sixteen Kingdoms

Northern Wei, a successor state of Dai, was the first of the Northern and Southern dynasties. It was founded by Tuoba Gui, posthumously Emperor Daowu of Northern Wei, in 386.[11]

From 388–9, he established dominion over the Kumoxi, Jieru, and Tutulin in the east. From 390–1, he defeated the Gaoju, Yuange, Helan, Gexi, Getulin, Chinu, and Chufu north of the Yellow River. From 391–2, he defeated the Xiongnu south of the Yellow River.[12]

In the summer of 395, the heir apparent of Later Yan, Murong Bao, attacked Northern Wei. Tuoba Gui chose not to confront him head on and fled west across the Yellow River, leaving the east undefended. When Murong Bao reached the east bank of the Yellow River, a series of protracted skirmished occurred, lasting until winter. At that point Murong Bao started to retreat, but Tuoba Gui overtook him with a column of cavalry at Shenhe Slope, northwest of modern Horinger. The entire Yan army was taken by surprise and routed on 8 December 395. Murong Chui led a new invasion into Later Yan territory in 396 and defeated an army near Pingcheng, but the offensive came to an abrupt halt when he grew ill and died. The momentum reversed and Yan armies captured Bing Province in the fall, Zhongshan in 397, and Ye city in 398.[13]

Tuoba Gui died in 409 and was succeeded by his son, Tuoba Si, posthumously Emperor Mingyuan of Northern Wei. Tuoba Si was heavily involved in Chinese poetry and literature and lacked the martial drive of his predecessor. Under his reign, there were two campaigns against the Rouran to the north.[14]

Tuoba Si died in 423 and was succeeded by his son Tuoba Tao, posthumously Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei. Tuoba Tao was the polar opposite of his father. According to Sima Guang, the heir of Tuoba Si was courageous and stalwart, often leading the charge in assaulting heavily defended cities, and acted indifferently towards the sight of death. In 426 he attacked the kingdom of Xia, taking Chang'an and Tongwancheng in 427. However Chang'an was retaken the next year. In 430 Northern Wei took Luoyang from the Liu Song dynasty, conquered Northern Yan in 436, and Northern Liang in 439. Thus ended the Sixteen Kingdoms.[14]

Tao's tyranny

After conquering Northern Liang, Tuoba Tao crushed the rebellion of Ge Wu in Guanzhong and at the suggestion of Cui Hao, instigated proscription campaigns against Buddhism. In 449, he crushed the Rouran in battle and retaliated against a Liu Song invasion with his punitive expedition, reaching as far as Guabu (southeast of Luhe, Jiangsu).[15] He was killed in 452 by a eunuch, Zong Ai, who was killed by Lu Li and others. They installed Tuoba Jun, posthumously Emperor Wencheng of Northern Wei.[16]

Sinicization

In 465, Tuoba Jun died and was succeeded by Tuoba Hong, posthumously Emperor Xianwen of Northern Wei. Under his reign, Northern Wei invaded the Liu Song dynasty and Qingzhou and Jizhou (冀州) (north Jiangsu).[15]

In 471, Tuoba Hong abdicated in favor of Yuan Hong, posthumously Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei.[15] Hong's reign saw increasing sinicization at the court. In 494, Hong secretly moved the court to Luoyang under the disguise of a campaign. In 495, he banned the Xianbei language at court. Non-Chinese languages were forbidden for all officials under the age of 30 and Xianbei surnames were replaced with Chinese names: Tuoba became Yuan. Xianbei clothing was also forbidden. Xianbei ranks were subsumed under the Chinese ones, and all Xianbei families were ranked using the new system. In 496, Xianbei nobles and generals rebelled in the north but were defeated. Even Hong's own son opposed the new policies, for which he was forced to commit suicide.[17]

In 499, Tuoba Hong died and was succeeded by Yuan Ke, posthumously Emperor Xuanwu of Northern Wei.[18] Under Yuan Ke, Northern Wei invaded the Liang dynasty and conquered Yiyangin 504 and Chouchi in 506.[18][19] They were however defeated at Zhongli (northeast of Fengyang, Anhui).[18] A Liang counterattack saw the loss of Qushan (southwest of Lianyungang, Jiangsu) in 512.[20]

in 515, Yuan Ke died and was succeeded by Yuan Xu, posthumously Emperor Xiaoming of Northern Wei.

Collapse

In 523, drought and famine afflicted the northern frontier. Garrison commanders refused to distribute rations, causing the Six Frontier Towns to rebel under Poliuhan Baling. He was soon defeated with the aid of the Rouran khan Yujiulü Anagui, but northern refugees entered Hubei and also rebelled under Du Luozhou and Ge Rong.[20]

In 528, Yuan Xu was poisoned by her mother and died. Erzhu Rong, a Jie general, took control of the capital and killed the empress and her son, Yuan Zhao. He enthroned Yuan Ziyou, posthumously Emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei. Then with only 7,000 cavalry, Erzhu defeated Ge Rong's rebels. He enlisted the surrendered into his army, becoming the de facto ruler of Northern Wei. His victory was short lived, and Yuan Ziyou killed him in an ambush in 530. Erzhu Rong's heir, Erzhu Zhao, retaliated by sacking the capital and killing the emperor, replacing him with Yuan Ye. Erzhu Zhao failed to command his predecessor's former troops and they defected to Gao Huan.[21]

In 531, Gao Huan established an independent regime in Hebei. Being a Chinese raised in the Xianbei culture, he commanded not only the loyalty of Xianbei frontiersmen, but also that of the Han Chinese. With his supporters, Gao decisively defeated Erzhu Zhao in late spring of 532. He enthroned Yuan Xiu, posthumously Emperor Xiaowu of Northern Wei.[22]

In 534, Yuan Xiu fled to Chang'an under the regime of Yuwen Tai. In response, Gao Huan evicted Luoyang of its entire population and moved them to Ye city. Yuan Shanjian, posthumously Emperor Xiaojing of Eastern Wei, was enthroned under the eastern regime.[23]

In 535, Yuan Xiu was killed by Yuwen Tai, who replaced him with Yuan Baoju, posthumously Emperor Wen of Western Wei. Thus ended the Northern Wei.[24]

Northern Wei cavalry

Northern Wei cavalry Northern Wei cavalry

Northern Wei cavalry Northern Wei cavalry

Northern Wei cavalry Northern Wei cavalry

Northern Wei cavalry Northern Wei cavalry

Northern Wei cavalry.jpg.webp) Northern Wei cavalry

Northern Wei cavalry Western Wei horse rider (possibly flag bearer or messenger)

Western Wei horse rider (possibly flag bearer or messenger)

Western and Eastern Wei

In 537, Gao Huan launched a three pronged attacked on Western Wei. When one column was crushed by a concentration of 6,000 cavalry under Yuwen Tai, Gao retreated. Gao made a second attempt with a force of 100,000. The resulting Battle of Shayuan on 19 November saw Gao's entire force defeated in a surprise ambush by 7,000 heavy cavalry. The eastern army lost more than half its men.[24]

In 538, Western Wei attacked Luoyang but was defeated.[25]

In 542, Gao Huan tried to take the fortress of Yubi, which blocked his way into Guanzhong. After a nine day siege, he withdrew due to a snowstorm.[25]

In 543, Yuwent Tai tried to take Luoyang again and failed.[25]

In 546, Gao Huan tried to take Yubi again. He failed and died a few weeks later.

Gao’s men began by building an earthen mound to overlook the south wall of the fortress, but the defenders were able to counter by adding to the height of their towers. The attackers then tried tunnelling, but the defenders intercepted the tunnels by digging a deep trench inside and parallel to the south wall. When the attackers tried to weaken the wall with a sort of battering ram, the defenders lowered a cloth screen from the top of the wall to soften its impact. Gao Huan’s men eventually succeeded in undermining the wall and causing a small section to collapse, but the Western Wei defenders quickly filled the gap with a makeshift palisade. After spending thousands of lives to no avail, Gao abandoned the siege and withdrew to Taiyuan. He died only a few weeks later.[26]

— David Graff

In 550, Gao Yang replaced the Eastern Wei with his own dynasty, Northern Qi.[24]

Western Wei invaded the Liang dynasty in 553 and conquered the Sichuan region. They killed Emperor Yuan of Liang the next year.[27]

In 556, Yuwen Tai died.[27]

In 557, Yuwen Hu replaced Western Wei with Northern Zhou.[27]

| Tuoba / Yuan clan, Wei emperors family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Legend:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Northern Qi (550–577)

Northern Qi was founded in 550 by Gao Yang, posthumously Emperor Wenxuan of Northern Qi.[24]

In 553, the Rouran submitted to Northern Qi after being defeated by the Göktürks.[27]

In 556, Northern Qi attacked Jiankang but was repelled.[27]

In 559, Gao Yang died and was succeeded by Gao Yin, posthumously Emperor Fei of Northern Qi.[27]

In 560, Gao Yin was deposed by Gao Yan, posthumously Emperor Xiaozhao of Northern Qi.[27]

In 561, Gao Yan died and was succeeded by Gao Zhan, posthumously Emperor Wucheng of Northern Qi.[27]

In 565, Northern Qi invaded Northern Zhou but was repelled. Gao Zhan abdicated to Gao Wei.[27]

In 573, the Chen dynasty invaded and conquered the Huai River valley.[28]

In 575, Northern Zhou mobilized 170,000 men for an attack on Luoyang. After initial success, their emperor fell ill and were forced to retreat.[28]

On 10 November 576, Northern Zhou struck at Pingyang with an army 145,000. With 60,000, the emperor took the city. As Gao Wei approached Pingyang, the enemies retreated with only 10,000 remaining in the city. On 10 January, 577, Northern Zhou returned with 80,000 men deployed in battle formation covering a wide perimeter. Gao Wei decided to engage the enemy army. When his left wing showed signs of collapsing, he fled, demoralizing his army and causing it to collapse. The Zhou army continued to advance, reaching Taiyuan on 17 January. On the 20th, 40,000 troops sallied out and were defeated. While they were retreating back into the city, the Zhou army scaled the walls. A Qi counterattack that night pushed back the invaders. On 21 January, the Zhou army breached the eastern gate and took the city. On 22 February 577, Ye city fell the Zhou. Gao Wei was captured and killed in 578.[29]

| Northern Qi emperors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Northern Zhou (557–581)

Northern Zhou was founded by Yuwen Hu in 557. However Yuwen Hu never became emperor, instead placing Yuwen Jue on the throne, posthumously Emperor Xiaomin of Northern Zhou. Yuwen Jue tried to size power from Yuwen Hu, so Yuwen Hu had him killed and replaced with Yuwen Yu, posthumously Emperor Ming of Northern Zhou.[27]

In 560, Yuwen Hu killed Yuwen Yu and replaced him with Yuwen Yong, posthumously Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou.[27]

In 561, the Chen dynasty invaded, seizing North Hubei.[27]

In 565, an attack on Northern Qi was repelled.[28]

In 572, Yuwen Yong killed Yuwen Hu and seized complete power over the dynasty.[28]

On 10 November 576, Northern Zhou struck at Pingyang with an army 145,000. With 60,000, the emperor took the city. As Gao Wei approached Pingyang, the enemies retreated with only 10,000 remaining in the city. On 10 January, 577, Northern Zhou returned with 80,000 men deployed in battle formation covering a wide perimeter. Gao Wei decided to engage the enemy army. When his left wing showed signs of collapsing, he fled, demoralizing his army and causing it to collapse. The Zhou army continued to advance, reaching Taiyuan on 17 January. On the 20th, 40,000 troops sallied out and were defeated. While they were retreating back into the city, the Zhou army scaled the walls. A Qi counterattack that night pushed back the invaders. On 21 January, the Zhou army breached the eastern gate and took the city. On 22 February 577, Ye city fell the Zhou. Gao Wei was captured and killed in 578.[29]

In 578, Yuwen Yong died as he was preparing to lead an expedition against the Göktürks. He was succeeded by Yuwen Yun, posthumously Emperor Xuan of Northern Zhou.[28]

In 579, Yuwen Yun abdicated to Yuwen Chan, posthumously Emperor Jing of Northern Zhou. He was only six years old at the time and real power resided in Yang Jian.[28]

In 580, Northern Zhou seized territory north of the Changjiang. Yuchi Jiong and Wang Qian rebelled but were defeated.[28]

On 4 March 581, Yang Jian deposed Yuwen Chan, and declared himself Emperor of the Sui dynasty.[30]

| Northern Zhou emperors family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sui dynasty

In 587, the Sui dynasty annexed Western Liang and invaded the Chen dynasty with 518,000 men the following year. The Sui army took Jiankang in 589, annexing Chen and ending the era of Northern and Southern dynasties.[30]

Southern dynasties

Liu Song (420–479)

In 420, Liu Yu, posthumously Emperor Wu of Liu Song, usurped the Jin throne and replaced it with his own Liu Song dynasty.[31] Liu Yu was originally the son of a low ranking official and his family was described as "poor".[32] During the waning years of the Jin dynasty, Liu Yu proved himself to be an exceptionally capable commander, gifted in the use of the glaive, and worked his way up the military hierarchy. By the year 420, Liu Yu had become the dominant military power in the empire.[33]

In 422, Liu Yu died and was succeeded by his son Liu Yifu, posthumously Emperor Shao of Liu Song.[33]

In 424, Liu Yifu was deposed and succeeded by Liu Yilong, posthumously Emperor Wen of Liu Song.[33]

In 430, Northern Wei took Luoyang from Song.[34]

In 434, Song retook Hanzhong from Chouchi.[34]

In 442, Xiao Daocheng attacked the Nanman north of the Han River.[35]

In 449, Shen Qingzhi attacked the Nanman north of the Han River, taking 28,000 prisoners.[1]

In 450, Song invaded Northern Wei but was defeated.[15]

In 453, Liu Yilong was murdered by Liu Shao, who was then killed by Liu Jun, posthumously Emperor Xiaowu of Liu Song. Liu Jun spent his reign killing his brothers and checking the power of his kin.[36]

In 464, Liu Jun died, sparking a civil war.[36]

In 466, Liu Yu, posthumously Emperor Ming of Liu Song, defeated the contenders and ended the civil war.[36]

In 467, Northern Wei invaded, taking territory north and west of the Huai River.[15]

In 469, Northern Wei took Qingzhou and Jizhou (冀州) (north Jiangsu)[15]

In 472, Liu Yu died and was succeeded by Liu Yu, posthumously Emperor Houfei of Liu Song. The former emperor's brother rebelled but was defeated by the general Xiao Daocheng.[36]

In 477, Liu Yu was killed by Xiao Daocheng and was succeeded by Liu Zhun, posthumously Emperor Shun of Liu Song. Xiao Daocheng went to war with provincial governor Shen Youzhi, eventually winning the next year.[36]

In 479, Xiao Daocheng deposed the last emperor of Liu Song and took the title for himself, as Emperor of Southern Qi, posthumously Emperor Gao of Southern Qi.[18]

| Liu Song | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Southern Qi (479–502)

The Southern Qi dynasty founded by Xiao Daocheng in 479 lasted a mere 22 years. Xiao Daocheng died in 482 and was succeeded by Xiao Ze, posthumously Emperor Wu of Southern Qi. Xiao Ze died in 482 and was succeeded by Xiao Zhaoye. Xiao Luan assassinated him in 494 and became emperor, posthumously Emperor Ming of Southern Qi. When Xiao Luan died in 498 and Xiao Baojuan came to the throne, a series of plots and revolts by regional governors occurred. In 500, an imperial cousin named Xiao Yan raised 30,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry in revolt. Northern Wei also invaded at this point and took territory south of the Huai River. In 501, Xiao Baojuan's subordinates killed him and surrendered Jiankang to Xiao Yan. In 502, Xiao Yan proclaimed himself Emperor of the Liang dynasty, posthumously Emperor Wu of Liang.[36]

| Southern Qi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Liang (502–557)

The Liang dynasty founded by Xiao Yan in 502 survived for 55 years, with the founder ruling for 48 of those years. To fund the state treasury, the emperor donated himself to a Buddhist monastery on three occasions and forced his ministers to pay a ransom for him each time.

In 504, Northern Wei conquered Yiyang.[18]

In 507, a Northern Wei army was defeated at Zhongli (northeast of Fengyang, Anhui).[18]

In 518, Liang retook Qushan (southwest of Lianyungang, Jiangsu).[20]

In 528, Liang briefly occupied Luoyang before being expelled.[37]

In 541, Lý Bôn rebelled and attacked Liang officials.[38]

In 544, Lý Bôn established the Early Lý dynasty and became Lý Nam Đế (Southern Emperor).[38]

In 545, Chen Baxian drove Lý Nam Đế into the mountains, where he is eventually killed, but resistance continued under Lý Thiên Bảo.[38]

In 548, the frontier general Hou Jing rebelled, took Jiankang, and proclaimed himself emperor in 551.[24]

In 549, Hou Jing seized Taicheng. Eastern Wei took territory south of the Huai River. Xiao Yan died and was succeeded by Xiao Gang, posthumously Emperor Jianwen of Liang.[24]

In 551, Hou Jing killed Xiao Gang and declared himself emperor.[24]

In 552, Wang Sengbian and Chen Baxian retook Jiankang while Hou Jing was killed. Xiao Ji declared himself emperor in Jiangling but was killed the next year. Xiao Yi became emperor, posthumously Emperor Yuan of Liang.[27]

In 553, Western Wei conquered Sichuan.[27]

In 554, Xiao Yi was captured by Western Wei and killed.[27]

In 555, Wang Sengbian set up Xiao Yuanming as emperor but Chen Baxian killed Sengbian and set up Xiao Fangzhi, posthumously Emperor Jing of Liang.[27]

In 556, Northern Qi attacked Jiankang but was repelled.[27]

In 557, Chen Baxian replaced the Liang dynasty with his own Chen dynasty[27]

| Liang dynasty and Western Liang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

– Liang emperors – Western Liang emperors – Liang throne pretenders

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chen dynasty (557–589)

The Chen dynasty was founded by Chen Baxian, posthumously Emperor Wen of Chen, in 557. It was immediately invaded in 558 by Western Liang, which took Changsha and Wuling[27] The next year, Chen Baxian died and was succeeded by Chen Qian, posthumously Emperor Wen of Chen.[27]

In 561, Chen attacked Northern Zhou and conquered Hubei.[27]

In 566, Chen Qian died and was succeeded by Chen Bozong, posthumously Emperor Fei of Chen.[28]

In 568, Chen Bozong was deposed and succeeded by Chen Xu, posthumously Emperor Xuan of Chen.[28]

In 573, Chen invaded Northern Qi, conquering the Huai River valley and taking territory north of the Changjiang.[28]

In 575, a Northern Qi army was defeated at Lüliang.[28]

In 578, a Chen invasion of Northern Qi was defeated at Pengcheng.[28]

In 580, Northern Zhou seized territory north of the Changjiang.[28]

In 582, Chen Xu died and was succeeded by Chen Shubao.[30]

In 588, the Sui dynasty invaded and annexed the Chen dynasty the following year.[30]

| Chen dynasty emperors family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Graff 2001, p. 83.

- Graff 2001, p. 84.

- Graff 2001, p. 99.

- Graff 2001, p. 108.

- Graff 2001, p. 109.

- Graff 110.

- Graff 2001, p. 115.

- Peers 2006, p. 94.

- Peers 2006, p. 99.

- Wagner 2008, p. 256.

- Xiong 2009, p. xcvii.

- Graff 2001, p. 69-70.

- Graff 2001, p. 71.

- Graff 2001, p. 72.

- Xiong 2009, p. c.

- Xiong 2009, p. 542.

- Graff 2001, p. 98.

- Xiong 2009, p. ci.

- Xiong 2009, p. 414.

- Xiong 2009, p. cii.

- Graff 2001, p. 101.

- Graff 2001, p. 102.

- Graff 2001, p. 103.

- Xiong 2009, p. ciii.

- Graff 2001, p. 105.

- Graff 2001, p. 106.

- Xiong 2009, p. civ.

- Xiong 2009, p. cv.

- Graff 2001, p. 113.

- Xiong 2009, p. cvi.

- Graff 2001, p. 78.

- Graff 2001, p. 90.

- Graff 2001, p. 87.

- Xiong 2009, p. xcix.

- Graff 2001, p. 91.

- Graff 2001, p. 88.

- Graff 2001, p. 125.

- Taylor 2013.

Bibliography

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2004), Generals of the South

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2004b), Generals of the South 2

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007), A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms, Brill

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2010), Imperial Warlord, Brill

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2017), Fire Over Luoyang: A History of the Later Han Dynasty, 23-220 AD, Brill

- di Cosmo, Nicola (2009), Military Culture in Imperial China, Harvard University Press

- Graff, David A. (2001), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Routledge

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War: Military practice in seventh-century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Lee, Peter H. (1992), Sourcebook of Korean Civilization 1, Columbia University Press

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Lorge, Peter A. (2011), Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-87881-4

- Lorge, Peter (2015), The Reunification of China: Peace through War under the Song Dynasty, Cambridge University Press

- Peers, C.J. (1990), Ancient Chinese Armies: 1500-200BC, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1992), Medieval Chinese Armies: 1260-1520, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1995), Imperial Chinese Armies (1): 200BC-AD589, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1996), Imperial Chinese Armies (2): 590-1260AD, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (2006), Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC - AD 1840, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Peers, Chris (2013), Battles of Ancient China, Pen & Sword Military

- Shin, Michael D. (2014), Korean History in Maps, Cambridge University Press

- Taylor, Jay (1983), The Birth of the Vietnamese, University of California Press

- Taylor, K.W. (2013), A History of the Vietnamese, Cambridge University Press

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0810860538

- Wagner, Donald B. (2008), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5-11: Ferrous Metallurgy, Cambridge University Press