Miramichi River

The Miramichi River /ˌmɪrəmɪˈʃiː/ is a river located in the east-central part of New Brunswick, Canada.[1][2] The river drains into Miramichi Bay in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The name may have been derived from the Montagnais words "Maissimeu Assi" (meaning Mi'kmaq Land), and it is today the namesake of the Miramichi Herald at the Canadian Heraldic Authority.

Geography

The Miramichi River watershed drains a territory comprising one-quarter of New Brunswick's territory, measuring approximately 13,000 km² of which 300 km² is an estuarine environment on the inner part of Miramichi Bay. The watershed roughly corresponds to Northumberland County, but also includes sections of Victoria County, Carleton County, and York County and smaller parts of Gloucester County and Sunbury County.

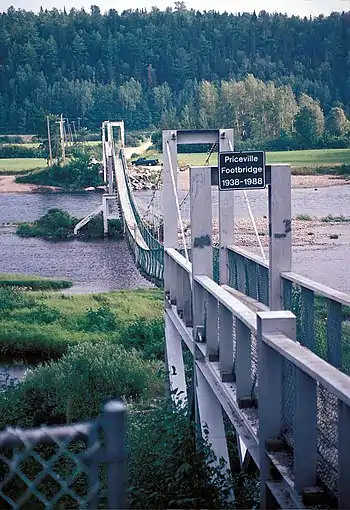

The Miramichi River meander length measures approximately 250 km and comprises two important branches, the Southwest Miramichi River and the Northwest Miramichi River, each having their respective tributaries. Nearly every bend in the river, from Push and Be Damned Rapids to the Turnip Patch has a distinctive name, reflecting the importance of the river to fishermen, canoeists, and lumbermen. Tides reach upriver in the Miramichi system to Sunny Corner on the Northwest Miramichi and to Renous-Quarryville on the Southwest Miramichi — a distance of approximately 70 km inland from the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The two branches combine at Newcastle where the river becomes navigable to ocean-going vessels.

The estuarine portion of the Miramichi River downriver from Newcastle in the city of Miramichi flows through a drowned river valley. Sea level rise in Miramichi Bay has flooded the mouth of the Miramichi River with saltwater. The estuary comprises the inner portion of Miramichi Bay and is protected from ocean storms in the Gulf of St. Lawrence by barrier islands. The estuary is significant in that it is a highly productive ecosystem, despite its relatively small size. The estuary receives the freshwater discharge from the Miramichi River and its tributaries, mixing with organic materials from the surrounding shorelines and the saltwater inundation from the Gulf of St. Lawrence, itself an estuary and the largest on the planet.

The estuary is a highly dynamic environment, ranging from the high outflows of freshwater during the spring freshet, to the low outflow and rising saltwater content during the summer period, to fall ocean storms and nor'easters that reshape the barrier islands and the old river channel that forms the navigation channel for ocean-going ships heading to ports at Chatham and Newcastle, to the winter covering of sea ice that encases the entire estuary. The inner bay measures only 4 m deep on average, with the navigation channel measuring only 6–10 m, resulting in significant warming of estuarine waters during the summer months. The diurnal tide cycle ranges only 1 m on average.

Tributaries

Important tributaries include:

Miramichi River

- Bartibog River

- Napan River

- Bay du Vin River

- Black River

- Northwest Miramichi River

- Sevogle River

- Little Southwest Miramichi River

- North-Pole River

- Tomogonops River

- Portage River

- Little River

- Southwest Miramichi River

Geology

Rising in the Silurian and Ordovician rocks of the Miramichi Highlands, an extension of the Appalachian Mountains, the tributaries of the Miramichi River flow eastward into the New Brunswick Lowland, which dominates the eastern and central part of the province along the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Erosion has created the "Miramichi River valley" (also shortened to just "Miramichi Valley"), through which the Northwest and Southwest Miramichi rivers flow. Throughout the course of both branches to Newcastle, New Brunswick, they are framed by heavily forested low hills. The highest peaks in the Miramichi River watershed, include Big Bald Mountain and the Christmas Mountains, extending to 750 m above sea level.

Soils in the Miramichi River watershed are typically acidic with shallow topsoil, lending to poor suitability for agriculture. The shorelines of the estuarine portion of the Miramichi River exposes newer rocks belonging to the Carboniferous period and underlay the sandy topsoil, however some coastal land is low lying and suffers poor drainage. Sandstone rocks are visible along the river banks.

Fisheries

The Miramichi River and its tributaries originally supported one of the largest populations of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in North America. The Atlantic salmon is an anadromous fish, that is, one that is hatched and grows briefly in freshwater and then migrates to salt water while immature to grow to maturity, before returning to fresh water to spawn and complete their life cycle. The Miramichi River still maintains a reasonably healthy, self-sustaining run of Atlantic salmon, as well as lesser runs of other anadromous fish such as American Shad, smelt, herring and sea-run brook trout. About one-half of the sport catch of Atlantic salmon in North America are landed on the Miramichi River and its tributaries currently.

Atlantic salmon fishing is restricted to fly fishing only and all large salmon caught must be released alive to protect the spawning population. Since this fishery is highly regulated, all anglers should contact the New Brunswick Dept. of Natural Resources to obtain the specific rules and regulations for each river and tributary in the Province of New Brunswick prior to fishing, as special licences, salmon "tags" and permits are required, and certain sections of tributaries and the main river are closed to fishing from time to time to protect salmon brood stocks.

The annual salmon runs start in mid-June and continue through late October, when spawning commences in earnest. It is believed that distinct runs of salmon destined for specific tributaries occur at different times of the year, with those fish headed for the upper reaches of the watershed entering the river earlier than those that spawn in the lower tributaries.

Popular salmon flies on the Miramichi River include the Black Bear series, the Cosseboom series, Butterfly, Oriole, and the Blackville Special. Deerhair flies such as the "Buck Bug" or the "Green Machine" are also quite successful. Major portions of the Miramichi River salmon fishing waters are controlled by private clubs and outfitters, with "public water" that is available to all very limited. Further, all non-resident anglers must hire a registered guide to fish for Atlantic salmon in New Brunswick. Guides can be inquired for in the village of Doaktown and through Dept. of Natural Resources offices.

Environmental history

The Miramichi River has a significant environmental history which has brought negative attention to the province of New Brunswick. Known as one of the greatest salmon streams in North America, this waterway is frequented for both recreational and subsistence fishing. In the early 1950s the Miramichi area began having a spruce budworm problem which was affecting the trees purposed for the local pulp and paper industry. To combat the issue, a solution of the chemical DDT was sprayed aerially over the Miramichi area. Assuming the DDT would only harm the budworms, planes kept their spraying jets on over the entire region including over the major waterways. This chemical spraying project adversely affected the river as well as the living things within it, particularly the wild salmon. Soon after the spraying project, mass quantities of dead salmon washed up onto the riverbeds of the Miramichi River. Approximately only 1/3rd of the hatchlings and 1/6th of the already established salmon population survived. The spraying affected the salmon indirectly as well by eliminating the insect population which the fish depended on as a food source. Combating the spruce budworm problem by spraying DDT ultimately altered the entire ecosystem of the Miramichi River. This event was documented in a famous environmental text, Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, in 1962. Silent Spring had a huge influence on the 20th century environmental movement and shed light on issues in small areas such as Miramichi, New Brunswick. The emergence of the environmental movement in New Brunswick catalyzed involvement from a variety of different social groups to target the issue. Local media outlets, scientists, outdoors enthusiasts and members of the general public got involved. Eventually the federal government placed restrictions on DDT spraying in the province. This series of events ultimately demonstrated that industrial development has negative impacts on the environment. [3] [4] [5]

See also

References

- Rayburn, A. (1975) Geographical Names of New Brunswick. Toponymy Study 2. Surveys and Mapping Branch, Energy Mines and Resources Canada, Ottawa

- Geographical Names of Canada "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-02-07. Retrieved 2009-02-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Carson, Rachel, Lois Darling, and Louis Darling. 1962. Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- McLaughlin, Mark J. 2012. "Green Shoots: Aerial Insecticide Spraying and the Growth of Environmental Consciousness in New Brunswick, 1952-1973". Acadiensis. 40 (1): 3.

- Bill Freedman, Environmental Ecology: The Impacts of Pollution and other Stresses on Ecosystem Structure and Function (Toronto: Academic Press Inc., 1989).