Musée de Cluny

The Musée de Cluny ("Cluny Museum", French pronunciation: [myze də klyni]), also known as Musée national du Moyen Âge – Thermes et hôtel de Cluny ("National Museum of the Middle Ages – Cluny thermal baths and mansion), is a museum of the Middle Ages in Paris, France. It is located in the Latin quarter in the 5th arrondissement of Paris at 6 Place Paul-Painlevé, south of the Boulevard Saint-Germain, between the Boulevard Saint-Michel and the Rue Saint-Jacques.

The Hôtel de Cluny is partially constructed on the remnants of the third century Gallo-Roman baths known as the Thermes de Cluny, thermal baths from the Roman era of Gaul. The museum consists of two buildings: the frigidarium ("cooling room"), within the vestiges of the Thermes de Cluny, and the Hôtel de Cluny itself, which houses its collections. The frigidarium is about 6,000 square meters.[1]

The museum houses a vast collection of objects and art from the Middle Ages. Among the principal holdings of the museum are the six tapestries of The Lady and the Unicorn (La Dame à la licorne).

History

The building itself is a rare extant example of the civic architecture of medieval Paris. It was formerly the town house (hôtel) of the abbots of Cluny. The first Cluny hôtel was built after the Cluny order acquired the Ancient thermal baths in 1340. It was built by Pierre de Chaslus.[2] The structure was rebuilt by Jacques d'Amboise, abbot in commendam of Cluny 1485–1510; it combines Gothic and Renaissance elements. In 1843, it was refashioned into a public museum by Alexandre du Sommerard to preserve relics of France's Gothic past.

Though it no longer possesses anything originally connected with the abbey of Cluny, the hôtel was at first part of a larger Cluniac complex that also included a building (no longer standing) for a religious college in the Place de la Sorbonne, just south of the present day Hôtel de Cluny along Boulevard Saint-Michel. Although originally intended for the use of the Cluny abbots, the residence was taken over by Jacques d'Amboise, Bishop of Clermont and Abbot of Jumièges, and rebuilt to its present form in the period of 1485-1500.[3] Occupants of the house over the years have included Mary Tudor, the sister of Henry VIII of England. She resided here in 1515 after the death of her husband Louis XII, whose successor, Francis I, kept her under surveillance, particularly to see if she was pregnant.[4] Seventeenth-century occupants included several papal nuncios, including Mazarin.[5]

In the 18th century, the tower of the Hôtel de Cluny was used as an observatory by the astronomer Charles Messier who, in 1771, published his observations in the landmark Messier catalog. In 1789, during the early years of the French Revolution, the hôtel was confiscated by the state, and for the next three decades served varying functions. At one point, it was owned by a physician who used the magnificent Flamboyant chapel on the first floor as a dissection room.[6] The hôtel also housed the printing press of Nicolas-Léger Moutard, the official printer of the Queen of France from 1774 to 1792. His printing press was located in the hôtel's chapel.[7]

In December 1832, Alexandre du Sommerard, a noted archeologist and art collector, bought the Hôtel de Cluny and installed his large collection of medieval and Renaissance objects.[8] Upon his death in 1842, the collection was purchased by the state; the building was opened as a museum in 1843, with Sommerard's son serving as its first curator. The buildings were restored by the architect Alber Lenoir and his son, Alexandre Lenoir.[9] The hotel was given historical monument status in 1846[10] and the thermal baths were granted the same status in 1862. The present-day gardens, opened in 1971, include a "forêt de la licorne" inspired by the famous tapestries housed inside.

Collections

The museum is 11,500 square feet, 6,500 of which are designed for expositions. It contains around 23,000 artifacts dating from the Gallo-Roman period up until the 16th century. There are currently 2,300 artifacts on display. The collections contain pieces from Europe, the Byzantine Empire, and the Islamic world of the Middle Ages.

L'Île-de-la-Cité, France

Much of the ancient collections can be found in the frigidarium. Here, the visitor can discover artifacts dating as far back as the romanization of the city of Parisii, such as the famous Boatman Pillar from the 1st century. This pillar was offered to the emperor Tiberius by the boatmen of Paris. It contains inscriptions dedicated to the Roman god Jupiter as well as Celtic references, making it a great example of the two cultures melding together on one artifact.[11] It was discovered in the 18th century, under the choir of Notre-Dame de Paris. Another ancient artifact that can be seen in the frigidarium is the Saint-Landry pillar. This pillar was sculpted in the second century on l'Île-de-la-Cité, and was discovered during the 19th century.

There is more ancient art outside of the frigidarium, including two lion heads made from rock crystal. The lion heads were made between the 4th and the 5th centuries in the Roman Empire. Although their purpose is not known, the most likely hypothesis is that they were made to decorate an imperial throne.

Beyond France

The Cluny also houses ancient Coptic art. The Coptic fabrics gained notoriety outside of Egypt and certain pieces. The linen medallion of Jason and Medea is kept in the Cluny today.

Between 1858 and 1860, twenty-six Visigoth crowns were discovered. This was one of the most important discoveries related to the medieval Iberian world. Of the original twenty-six crowns, there are 10 left today. The remaining crowns have been spread between two museums: the Palacio Real de Madrid and the Cluny. Today, the Cluny holds three of these crowns, as well as crosses, pendants and hanging chains from the same discovery. These items were symbols of royal power and date back to the 7th century. They were most likely offered to the religious establishments in Toledo, the then capital of Spain.[12]

Byzantine Art

Starting with the founding of the city in Constantinople in 330, the emperor Constantine began an era known as the Byzantine period. Between 843 and the fall of the Byzantine empire in 1204, the politics and art of this empire flourished. During this part of the Middle Ages in the West, the Byzantine art was a link to traditional literature, philosophy and Greco-Roman art.

One example is the noteworthy ivory sculpture from Constantinople called Ariane. Ariane dates back to the first half of the 6th century and was most likely produced to adorn a piece of furniture. The statue includes Ariane, fauns and a few Angels of Love. It is one of the most iconic examples of Byzantine ivory work.

Another famous piece of Byzantine ivory found in the Cluny is the plaque that depicts the crowning of Otto II. His father Otto I was crowned king of Rome on February 2, 962. This crowning marks the beginning of a renaissance in this part of Western Europe. Similar to Charlemagne, Otto I later took the title of Emperor Augustus. In 972, the emperor Otto II married the princess Théophano, who became the empress of Rome and can be seen in the ivory plaque as well.[13]

The Cluny also possesses a Byzantine coffer that contains mythological images and was produced around the year 1000. It was at this time that the Macedonian emperors ruled in Constantinople.

Romanesque Art

The term "Roman" art first appeared in 1818. It was used by Charles de Gerville to describe the art that comes after the Carolingian empire, but before Gothic art. Before the 19th century, most of the art from the Middle Ages was referred to as Gothic art. Romanesque art is defined by its use of light and color. The Romanesque artists are masters of volume and contrast. The paintings are relatively simple, focusing on the narrative. From the Romanesque period onward, reliquaries and other religious artifacts were no longer kept in crypts, and instead were displayed on the altars in churches. Visibility of faith was of the utmost importance at this time.[14]

In France

There are two central elements to Romanesque art: pedagogy and devotion. The evolution of faith is a common theme of these works. One example in the Cluny today is a capital that was made in Paris between 1030 and 1040. Referred to as the Majestic Christ capital, it was created for the Saint-Germain-des-Prés church, the product of a collaboration between two workshops. The Cluny also houses a series of twelve capitals from Saint-Germain-des-Prés made in the beginning of the 11th century.

Beyond France

The Cluny possesses Romanesque art from other countries as well, such as England, Italy and Spain. One of the more famous examples is the English crosier from the middle of the 12th century. This piece, made from ivory, displays multiple eagles and lions. Another famous work in ivory is the Italian 'Olifant' from the end of the 11th century. This piece was created from an elephant tusk and depicts the scene of Jesus' Ascension.[14]

There are also Romanesque art pieces from Catalonia at the Cluny. There is a series of eight capitals that come from the Saint Pere de Rodes church. One of the capitals depicts the Biblical story of Noah and another details the story of Abraham. Another piece from Catalonia is a statue of a female saint made from wood that dating to the second half of the 12th century.[15]

Work from Limoges

The Cluny houses many pieces from the famous enamel and gold workshops of Limoges. These workshops first started producing pieces in the second quarter of the 12th century. Limoges is located in the southwestern, central part of France; its gold and enameled masterpieces were collected throughout Europe by the end of the 12th century. The goldsmiths and other artists produced varying kinds of products including crosses, shrines, altarpieces, candlesticks and much more. They tended to be religious in nature.

One of the reasons that pieces from these workshops were so successful is because the materials were affordable. As such, they were able to produce in mass. Not only were they producing a lot of products, but products of quality as well. The colors were vivid and the subject matter was depicted with eloquence.

There are many pieces from Limoges at the Cluny today. Most notably are the two copper plaques from around the year 1190. One depicts the image of Saint Étienne and the other portrays the Three Wisemen. These two plaques decorated the main altar at Grandmont Abbey. The adoration of the Three Wisemen was a popular theme in pieces from Limoges and can be found in many of their works. A copper shrine from the year 1200 also depicts this theme.[16]

Gothic Art from France

The 1120s in Paris saw many changes in art and education. One theme that became vitally important in both arenas was the importance of light. The teachings of Plato and his student Platin emphasize the importance of light in the Creation story. This has parallels in changes happening architecturally in Paris at the same time. Supporting beams and arches are thinned to allow more space for windows to allow in more light. The Sainte-Chapelle, with its tall and beautiful stained glass windows, displays this change in architecture. The upper cathedral has 15 window bays that encircle the entire room, each 50 feet tall, giving the illusion that the visitor is surrounded by light.

Artists in 12th century Paris experimented artistically, exploring a new conception of space and the relationship between architecture, sculpture and stained glass, as seen in the Sainte-Chapelle. The Cluny houses many examples of this experimentation, such as 'double' capitals and statues that function as columns. There is a double capital that depicts two harpies facing each other that comes from the church at Saint-Denis, made between 1140 and 1145. Another artifact from Saint-Denis is the head from a statue-column of Queen Saba. This statue-column was produced in the 12th century.

The Cluny also has one of the most vast collections of stained-glass in France. Their collection includes 230 panels, medallions and fragments from the 12th century to the 14th. Sainte-Chapelle has donated some panels from their iconic stained-glass windows to the Cluny as well, including one panel that depicts the scene of Sampson and the lion.

If the 12th century was all about experimentation, the 13th and 14th centuries in Paris represent artistic maturity. It is at this time that the demand for non-religious art increases. There are two themes that dominate Parisian art in the 13th century: an interest in Antiquity and a new attention given to nature. One of the most famous examples at the Cluny is the statue of Adam made from limestone. Produced around 1260 in Paris, the statue depicts a nude Adam, who is covering himself with the leaves from a small tree. The influence of Antiquity is evident in this work.

Sainte-Chapelle not only donated pieces of stained-glass to the Cluny, but also six statues of apostles made from limestone. These statues were once located on the pillars of the upper chapel in Sainte-Chapelle, but can be seen in the Cluny today. These statues were made in the 1320s and originally came from Saint-Jacques aux Pèlerins.[17] These statues mark the peak of Parisian art from the middle of the 13th century.[18]

15th Century Art

In the 15th century, the opulence of urban elites encouraged artistic production as the demand for art increased. People began ordering artistic objects for everyday life, such as furniture, tapestries, ceramics, game pieces, etc. It is at this time that Paris became a capital of luxury. Here various artistic movements converged to create an 'international' gothic style. Artists began to sign their work, no longer desiring to remain anonymous.

This phenomenon is particularly evident in the considerable rise in demand for tapestries. The most famous tapestries at the Cluny today are that of the Lady and the Unicorn (La Dame à la licorne) series. There are six tapestries that make up this collection, each one representing a different sense. There are the five main senses (smell, hearing, taste, touch and sight) and it is the sixth tapestry that depicts the Lady with the Unicorn. The mysterious meaning of this sixth has produced multiple interpretations over the years. The most commonly embraced interpretation understands the Lady as representing It a sixth sense of morality or spirituality, as she puts aside her worldly wealth.[19]

Gallery

Hôtel de Cluny

Interior of the Roman baths

Interior of the Roman baths Element of the Pillar of the Boatmen, first quarter of the 1st century AD

Element of the Pillar of the Boatmen, first quarter of the 1st century AD Room of the Roman baths with capitals from the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés

Room of the Roman baths with capitals from the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés View of the courtyard and its gallery

View of the courtyard and its gallery View of the courtyard and tower

View of the courtyard and tower Tower door

Tower door Gable window

Gable window The well

The well View from the medieval garden

View from the medieval garden View of the garden arcades

View of the garden arcades Capitals under the arcades

Capitals under the arcades Vaults of the gothic chapel

Vaults of the gothic chapel One of the rooms of the museum

One of the rooms of the museum A colourful stained glass room in the museum

A colourful stained glass room in the museum

Collections

The Devil and a woman, stained glass, before 1248, from the Sainte-Chapelle

The Devil and a woman, stained glass, before 1248, from the Sainte-Chapelle Marble sculpture of the Presentation at the Temple, Burgundy, late 14th century

Marble sculpture of the Presentation at the Temple, Burgundy, late 14th century Reliquary of the Holy Umbilical Cord : Virgin and Child, gilded silver, France (Paris ?), 1407

Reliquary of the Holy Umbilical Cord : Virgin and Child, gilded silver, France (Paris ?), 1407

Adam, stone, Paris, around 1260, from the interior of the south transept of Notre-Dame de Paris

Adam, stone, Paris, around 1260, from the interior of the south transept of Notre-Dame de Paris Altarpiece of the Abbey of Saint-Denis, around 1250-1260, episodes of the life of Saint Benedict

Altarpiece of the Abbey of Saint-Denis, around 1250-1260, episodes of the life of Saint Benedict

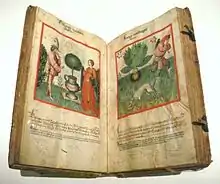

Illustrated Tacuinum Sanitatis of Ibn Butlan, Rhineland, 2nd half of 15th century

Illustrated Tacuinum Sanitatis of Ibn Butlan, Rhineland, 2nd half of 15th century Visigothic votive crowns from the Treasure of Guarrazar, Spain, 7th century

Visigothic votive crowns from the Treasure of Guarrazar, Spain, 7th century Ivory binding of Ariadne with Maenad, Satyr and Cupids, Constantinople, 6th century

Ivory binding of Ariadne with Maenad, Satyr and Cupids, Constantinople, 6th century Ivory crosier, Virgin and child with two angels, around 1300

Ivory crosier, Virgin and child with two angels, around 1300 Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, A mon seul désir, late 15th century.

Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, A mon seul désir, late 15th century. Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, Hearing

Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, Hearing Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, Taste, detail

Tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn, Taste, detail Head of the Queen of Sheba statue-column, limestone, 1137-1140. From the Saint-Denis church.

Head of the Queen of Sheba statue-column, limestone, 1137-1140. From the Saint-Denis church. The Presentation in the Temple, made during the second half of the 14th century,

The Presentation in the Temple, made during the second half of the 14th century, Madonna and Child, made around 1240-1250 in Paris.

Madonna and Child, made around 1240-1250 in Paris. The Swoon of the Virgin, made during the late Middle Ages.

The Swoon of the Virgin, made during the late Middle Ages. The ascent to Calvary, made around 1400.

The ascent to Calvary, made around 1400.

In culture

Herman Melville visited Paris in 1849, and the Hôtel de Cluny evidently fired his imagination. The structure figures prominently in Chapter 41 of Moby-Dick, when Ishmael, probing Ahab's "darker, deeper" motives, invokes the building as a symbol of man's noble but buried psyche.[20]

See also

Notes

- Bardiès-Fronty, Isabelle (2015). Musée de Cluny: Le Guide. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-7118-5631-2.

- Bardiès-Fronty, Isabelle (2015). Musée de Cluny: Le Guide. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais. p. 8. ISBN 978-2-7118-5631-2.

- Alistair Horne, Seven Ages of Paris, 2004:62.

- Cluny Museum – A journey to the Middle Ages"

- Horne 2004:65.

- Michelin, pp. 265-266.

- "Moutard, Nicolas-Léger (1742?-1803)". Identifiants et Référentiels.

- Album du Musée national du Moyen Age Thermes de Cluny, p. 5.

- "Les portes de Notre-Dame". Le Petit Journal. August 24, 1867.

- "Notice number PA00088431". ministère français de la culture.

- Bardiès-Fronty, Isabelle (2015). Musée de Cluny: Le Guide. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais. p. 16. ISBN 978-2-7118-5631-2.

- Bardiès-Fronty, Isabelle (2015). Musée de Cluny: Le Guide. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-2-7118-5631-2.

- Bardiès-Fronty, Isabelle (2015). Musée de Cluny: Le Guide. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais. p. 32. ISBN 978-2-7118-5631-2.

- Dectot, Xavier (2015). Musée de Cluny: Le Guide. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-2-7118-5631-2.

- "Chapiteau catalan: histoire de Noé". musée-moyenage.fr. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- Descatoire, Christine (2015). Musée de Cluny: Le Guide. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais. p. 63. ISBN 978-2-7118-5631-2.

- "Les Apôtres de Saint-Jacques-de-l'Hôpital". Catalogues des collections. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- Dectot, Xavier (2015). Musée de Cluny: Le Guide. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-2-7118-5631-2.

- Descatoire, Christine (2015). Musée de Cluny: Le Guide. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-2-7118-5631-2.

- Cotkin, George (2012-09-13), "Moby-Dick: Chapters 1 – 135", Dive Deeper, Oxford University Press, pp. 13–253, doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199855735.003.0003, ISBN 9780199855735

References

- This article incorporates text translated from the French Wikipedia article Musée de Cluny, licensed under cc-by-sa.

- Seven Ages of Paris, Alistair Horne, (ISBN 1-4000-3446-9) 2004

- Michelin, the Green Guide: Paris, (ISBN 2060008735), 2001

- Album du Musée national du Moyen Âge, Thermes de Cluny, Pierre-Yves Le Pogam, Dany Sandron (ISBN 2-7118-2777-1).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Musée national du Moyen Âge. |