Nebivolol

Nebivolol is a beta blocker used to treat high blood pressure and heart failure.[1] As with other β-blockers, it is generally a less preferred treatment for high blood pressure.[2] It may be used by itself or with other blood pressure medication.[2] It is taken by mouth.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Nebilet, Bystolic, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a608029 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 98% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 10 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney and fecal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

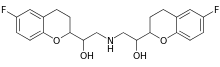

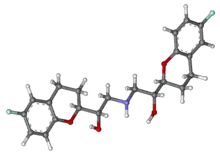

| Formula | C22H25F2NO4 |

| Molar mass | 405.442 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include dizziness, feeling tired, nausea, and headaches.[2] Serious side effects may include heart failure and bronchospasm.[2] Its use in pregnancy and breastfeeding is not recommended.[1][3] It works by blocking β1-adrenergic receptors in the heart and dilating blood vessels.[2][4]

Nebivolol was patented in 1983 and came into medical use in 1997.[5] It is available as a generic medication in the United Kingdom.[1] In 2017, it was the 144th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than four million prescriptions.[6][7]

Medical uses

It is used to treat high blood pressure and heart failure.[1]

ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, calcium-channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics are generally preferred over beta blockers for the treatment of high blood pressure.[2]

Contraindications

- Severe bradycardia

- Heart block greater than first degree

- Patients with cardiogenic shock

- Decompensated cardiac failure

- Sick sinus syndrome (unless a permanent pacemaker is in place)

- Patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class B)

- Patients who are hypersensitive to any component of this product.

Adverse reactions

- Headache

- Paresthesia

- Dizziness

- Slow heart rate

Pharmacology and biochemistry

β1-selectivity

Beta blockers help patients with cardiovascular disease by blocking β receptors, while many of the side-effects of these medications are caused by their blockade of β2 receptors.[8] For this reason, beta blockers that selectively block β1 adrenergic receptors (termed cardioselective or β1-selective beta blockers) produce fewer adverse effects (for instance, bronchoconstriction) than those drugs that non-selectively block both β1 and β2 receptors.

In a laboratory experiment conducted on biopsied heart tissue, nebivolol proved to be the most β1-selective of the β-blockers tested, being approximately 3.5 times more β1-selective than bisoprolol.[9] However, the drug's receptor selectivity in humans is more complex and depends on the drug dose and the genetic profile of the patient taking the medication.[10] The drug is highly cardioselective at 5 mg.[11] In addition, at doses above 10 mg, nebivolol loses its cardioselectivity and blocks both β1 and β2 receptors.[10] (While the recommended starting dose of nebivolol is 5 mg, sufficient control of blood pressure may require doses up to 40 mg).[10] Furthermore, nebivolol is also not cardioselective when taken by patients with a genetic makeup that makes them "poor metabolizers" of nebivolol (and other drugs) or with CYP2D6 inhibitors.[10] As many as 1 in 10 Caucasian people and even more black people are poor CYP2D6 metabolizers and therefore might benefit less from nebivolol's cardioselectivity although currently there are no directly comparable studies.

Nebivolol[12] while selectively blocking beta(1) receptor acts as a beta(3)-agonist. β3 receptors are found in the gallbladder, urinary bladder, and in brown adipose tissue. Their role in gallbladder physiology is unknown, but they are thought to play a role in lipolysis and thermogenesis in brown fat. In the urinary bladder it is thought to cause relaxation of the bladder and prevention of urination.[13] [14] [15]

Due to enzymatic inhibition, fluvoxamine increases the exposure to nebivolol and its active hydroxylated metabolite (4-OH-nebivolol) in healthy volunteers.[16]

Vasodilator action

Nebivolol is unique as a beta-blocker.[17] Unlike carvedilol, it has a nitric oxide (NO)-potentiating, vasodilatory effect via stimulation of β3 receptors.[18][19][20] Along with labetalol, celiprolol and carvedilol, it is one of four beta blockers to cause dilation of blood vessels in addition to effects on the heart.[20]

Antihypertensive effect

Nebivolol lowers blood pressure (BP) by reducing peripheral vascular resistance, and significantly increases stroke volume with preservation of cardiac output.[21] The net hemodynamic effect of nebivolol is the result of a balance between the depressant effects of beta-blockade and an action that maintains cardiac output.[22] Antihypertensive responses were significantly higher with nebivolol than with placebo in trials enrolling patient groups considered representative of the U.S. hypertensive population, in black people, and in those receiving concurrent treatment with other antihypertensive drugs.[23]

Pharmacology of side-effects

Several studies have suggested that nebivolol has reduced typical beta-blocker-related side effects, such as fatigue, clinical depression, bradycardia, or impotence.[24][25][26] However, according to the FDA[27]

Bystolic is associated with a number of serious risks. Bystolic is contraindicated in patients with severe bradycardia, heart block greater than first degree, cardiogenic shock, decompensated cardiac failure, sick sinus syndrome (unless a permanent pacemaker is in place), severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh > B) and in patients who are hypersensitive to any component of the product. Bystolic therapy is also associated with warnings regarding abrupt cessation of therapy, cardiac failure, angina and acute myocardial infarction, bronchospastic diseases, anesthesia and major surgery, diabetes and hypoglycemia, thyrotoxicosis, peripheral vascular disease, non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers use, as well as precautions regarding use with CYP2D6 inhibitors, impaired renal and hepatic function, and anaphylactic reactions. Finally, Bystolic is associated with other risks as described in the Adverse Reactions section of its PI. For example, a number of treatment-emergent adverse events with an incidence greater than or equal to 1 percent in Bystolic-treated patients and at a higher frequency than placebo-treated patients were identified in clinical studies, including headache, fatigue, and dizziness.

FDA warning letter about advertising claims

In late August 2008, the FDA issued a Warning Letter to Forest Laboratories citing exaggerated and misleading claims in their launch journal ad, in particular over claims of superiority and novelty of action.[27]

History

Mylan Laboratories licensed the U.S. and Canadian rights to nebivolol from Janssen Pharmaceutica N.V. in 2001. Nebivolol is already registered and successfully marketed in more than 50 countries, including the United States where it is marketed under the brand name Bystolic from Mylan Laboratories and Forest Laboratories. Nebivolol is manufactured by Forest Laboratories.

In India, nebivolol is available as Nebula (Zydus Healthcare Ltd), Nebizok (Eris life-sciences), Nebicip (Cipla ltd), Nebilong (Micro Labs), Nebistar (Lupin ltd), Nebicard (Torrent), Nubeta (Abbott Healthcare Pvt Ltd – India), and Nodon (Cadila Pharmaceuticals). In Greece and Italy, nebivolol is marketed by Menarini as Lobivon. In the Middle East, Russia and in Australia, it is marketed under the name Nebilet and in Pakistan it is marketed by The Searle Company Limited as Byscard.

References

- British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 154. ISBN 9780857113382.

- "Nebivolol Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "Nebivolol Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- de Boer RA, Voors AA, van Veldhuisen DJ (July 2007). "Nebivolol: third-generation beta-blockade". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 8 (10): 1539–50. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.10.1539. PMID 17661735. S2CID 24186687.

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 462. ISBN 9783527607495.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Nebivolol Hydrochloride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Tafreshi MJ, Weinacker AB (August 1999). "Beta-adrenergic-blocking agents in bronchospastic diseases: a therapeutic dilemma". Pharmacotherapy. 19 (8): 974–8. doi:10.1592/phco.19.11.974.31575. PMID 10453968. S2CID 32202416.

- Bundkirchen A, Brixius K, Bölck B, Nguyen Q, Schwinger RH (January 2003). "Beta 1-adrenoceptor selectivity of nebivolol and bisoprolol. A comparison of [3H]CGP 12.177 and [125I]iodocyanopindolol binding studies". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 460 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(02)02875-3. PMID 12535855.

- "Prescribing information for Bystolic" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- Nuttall SL, Routledge HC, Kendall MJ (June 2003). "A comparison of the beta1-selectivity of three beta1-selective beta-blockers". J Clin Pharm Ther. 28 (3): 179–86. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2710.2003.00477.x. PMID 12795776. S2CID 58760796.

- Rozec B, Erfanian M, Laurent K, Trochu JN, Gauthier C. "Nebivolol, a vasodilating selective beta(1)-blocker, is a beta(3)-adrenoceptor agonist in the nonfailing transplanted human heart". J Am Coll Cardiol. 53 (17): 1532–8. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.057. PMID 19389564.

- Sawa M, Harada H (2006). "Recent Developments in the Design of Orally Bioavailable β3-Adrenergic Receptor Agonists". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (1): 25–37. doi:10.2174/092986706775198006. PMID 16457637.

- Ferrer-Lorente R, Cabot C, Fernández-López JA, Alemany M (September 2005). "Combined effects of oleoyl-estrone and a β3-adrenergic agonist (CL316,243) on lipid stores of diet-induced overweight male Wistar rats". Life Sciences. 77 (16): 2051–8. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.008. PMID 15935402.

- Rang, H. P. (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-07145-4. Page 163

- Gheldiu, Ana-Maria; Vlase, Laurian; Popa, Adina; Briciu, Corina; Muntean, Dana; Bocsan, Corina; Buzoianu, Anca; Achim, Marcela; Tomuta, Ioan (2017). "Investigation of a Potential Pharmacokinetic Interaction Between Nebivolol and Fluvoxamine in Healthy Volunteers". Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. 20: 68–80. doi:10.18433/J3B61H. ISSN 1482-1826. PMID 28459657.

- Agabiti Rosei E, Rizzoni D (2007). "Metabolic profile of nebivolol, a beta-adrenoceptor antagonist with unique characteristics". Drugs. 67 (8): 1097–107. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767080-00001. PMID 17521213. S2CID 25807936.

- Galougahi, Keyvan (19 February 2016). "β3 Adrenergic Stimulation Restores Nitric Oxide/Redox Balance and Enhances Endothelial Function in Hyperglycemia". Journal of the American Heart Association. 5 (2): e002824. doi:10.1161/JAHA.115.002824. PMC 4802476. PMID 26896479.

- Weiss R (2006). "Nebivolol: a novel beta-blocker with nitric oxide-induced vasodilatation". Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2 (3): 303–8. doi:10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.3.303. PMC 1993984. PMID 17326335.

- Bakris G (May 2009). "An in-depth analysis of vasodilation in the management of hypertension: focus on adrenergic blockade". J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 53 (5): 379–87. doi:10.1097/FJC.0b013e31819fd501. PMID 19454898. S2CID 205598744.

- Kamp O, Sieswerda GT, Visser CA (August 2003). "Comparison of effects on systolic and diastolic left ventricular function of nebivolol versus atenolol in patients with uncomplicated essential hypertension". Am. J. Cardiol. 92 (3): 344–8. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00645-3. PMID 12888152.

- Gielen W, Cleophas TJ, Agrawal R (August 2006). "Nebivolol: a review of its clinical and pharmacological characteristics". Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 44 (8): 344–57. doi:10.5414/cpp44344. PMID 16961165.

- Baldwin CM, Keam SJ. Nebivolol: In the Treatment of Hypertension in the US. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2009; 9 (4): 253–260. Link text Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Pessina AC (December 2001). "Metabolic effects and safety profile of nebivolol". J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 38. Suppl 3: S33–5. doi:10.1097/00005344-200112003-00006. PMID 11811391. S2CID 20786564.

- Weber MA (December 2005). "The role of the new beta-blockers in treating cardiovascular disease". Am. J. Hypertens. 18 (12 Pt 2): 169S–176S. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.09.009. PMID 16373195.

- Poirier L, Cléroux J, Nadeau A, Lacourcière Y (August 2001). "Effects of nebivolol and atenolol on insulin sensitivity and haemodynamics in hypertensive patients". J. Hypertens. 19 (8): 1429–35. doi:10.1097/00004872-200108000-00011. PMID 11518851. S2CID 35105142.

- Thomas Abrams (2008-08-28). "Warning Letter" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2008.

FDA is not aware of any substantial evidence or substantial clinical experience that demonstrates that Bystolic represents a 'novel' or 'next generation' beta blocker for the treatment of hypertension. Indeed, we are not aware of any well-designed trials comparing Bystolic to other β-blockers. Furthermore, FDA is not aware of any data that would render Bystolic's mechanism of action 'unique.'

Check date values in:|access-date=(help)

External links

- "Nebivolol". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Nebivolol hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.