Ninth chord

In music theory, a ninth chord is a chord that encompasses the interval of a ninth when arranged in close position with the root in the bass.[1]

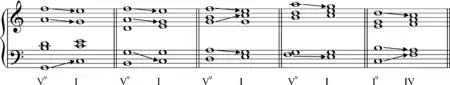

The ninth chord and its inversions exist today, or at least they can exist. The pupil will easily find examples in the literature [such as Schoenberg's Verklärte Nacht and Strauss's opera Salome]. It is not necessary to set up special laws for its treatment. If one wants to be careful, one will be able to use the laws that pertain to the seventh chords: that is, dissonances resolve by step downward, the root leaps a fourth upward.

Dominant ninth

|

There is a difference between a major ninth chord and a dominant ninth chord. A dominant ninth is the combination of a dominant chord (with a minor seventh) and a major ninth. A major ninth chord (e.g., Cmaj9), as an extended chord, adds the major seventh along with the ninth to the major triad. Thus, a Cmaj9 consists of C E G B and D ![]() play . When the symbol "9" is not preceded by the word "major" or "maj" (e.g., C9), the chord is a dominant ninth. That is, the implied seventh chord is a dominant seventh, i.e. a major triad plus the minor seventh, to which the ninth is added: e.g., a C9 consists of C, E, G, B♭ and D

play . When the symbol "9" is not preceded by the word "major" or "maj" (e.g., C9), the chord is a dominant ninth. That is, the implied seventh chord is a dominant seventh, i.e. a major triad plus the minor seventh, to which the ninth is added: e.g., a C9 consists of C, E, G, B♭ and D ![]() play . C dominant ninth (C9) would usually be expected to resolve to an F major chord (the implied key, C being the dominant of F). The ninth is commonly chromatically altered by half-step either up or down to create more tension and dissonance. Fétis tuned the chord 4:5:6:7:9.[6]

play . C dominant ninth (C9) would usually be expected to resolve to an F major chord (the implied key, C being the dominant of F). The ninth is commonly chromatically altered by half-step either up or down to create more tension and dissonance. Fétis tuned the chord 4:5:6:7:9.[6]

In the common practice period, "the root, 3rd, 7th, and 9th are the most common factors present in the V9 chord," with the 5th, "typically omitted".[3] The ninth and seventh usually resolve downward to the fifth and third of I.[3]

Example of tonic dominant ninth chords include Bobby Gentry's "Ode to Billie Joe" and Wild Cherry's "Play That Funky Music".[7] James Brown's "I Got You (I Feel Good)" features a striking dominant 9th arpeggio played staccato at the end of the opening 12-bar sequence. The opening phrase of Chopin's well-known "Minute Waltz" climaxes on a dominant 9th chord:

César Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major opens with a dominant ninth chord (E9) in the piano part. When the violin enters in the fifth bar, its melody articulates an arpeggio of this chord.

Debussy’s "Hommage a Rameau", the second of his first Book of Images for piano solo climaxes powerfully on a dominant 9th, expressed both as a chord and as a wide-ranging arpeggio:

.png.webp)

The starting point of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s piece for vocal sextet, Stimmung (1968) is a chord consisting of the notes B♭, F, B♭, D, A♭ and C.[8] According to Cook (1987, p.370),[9] Stimmung could, in terms of conventional tonal harmony, be viewed as ‘simply a dominant ninth chord that is subject to timbral variation. The notes the performers sing are harmonics 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 9 of the implied but absent fundamental—the B flat below the bass clef.’

Dominant minor ninth

| Component intervals from root | |

|---|---|

| minor ninth | |

| minor seventh | |

| perfect fifth | |

| major third | |

| root | |

| Tuning | |

| 8:10:12:14:17 | |

| Forte no. / | |

| 5-31 / |

- (Dominant minor ninth chord on C)

A dominant minor ninth chord consists of a dominant seventh chord and a minor ninth. In C: C E G B♭ D♭. Fétis tuned the chord 8:10:12:14:17.[6] In notation for jazz and popular music, this chord is often denoted, e.g., C7♭9. In Franz Schubert’s Song Der Erlkönig, a terrified child calls out to his father when he sees an apparition of the sinister Elf King. The dissonant voicing of the dominant minor ninth chord used here (C7♭9) is particularly effective in heightening the drama and sense of threat.

The chord of the ninth...is merely an additional note added to the chord of the flat seventh, which in the..minor mode a semitone above the eighth. In the latter case it is called the flat ninth, and is used in the minor keys almost as frequently as the flat seventh is in the major keys; but as its effect on the ear, when the fundamental tone or root is used, is rather harsh, its inversions alone are generally used. This latter chord, when occasionally changed enharmonically for the purpose of making sudden transitions or modulations into distant keys, gratifies the ear more than any other chord.

— John Smith (1853)[10]

(Extract from Schubert's 'Der Erlkönig.' Link to passage)

Writing about this passage, Taruskin (2010, p.149) remarks on the “unprecedented… level of dissonance at the boy’s outcries…The voice has the ninth, pitched above, and the left hand has the seventh, pitched below. The result is a virtual ‘tone cluster’…the harmonic logic of these progressions, within the rules of composition Schubert was taught, can certainly be demonstrated. That logic, however, is not what appeals so strongly to the listener’s imagination; rather it is the calculated impression (or illusion) of wild abandon.”[11]

Minor ninth

| Component intervals from root | |

|---|---|

| major ninth | |

| minor seventh | |

| perfect fifth | |

| minor third | |

| root | |

| Tuning | |

| 20:24:30:36:45 | |

| Forte no. / | |

| 5-27 / |

- (C minor ninth chord)

The minor ninth chord consist of a minor seventh chord and a major ninth. The formula is 1, ♭3, 5, ♭7, 9. This chord is written as Cm9. This chord has a more "bluesy" sound and fits very well with the dominant ninth.

Major ninth

| Component intervals from root | |

|---|---|

| major ninth | |

| major seventh | |

| perfect fifth | |

| major third | |

| root | |

| Tuning | |

| 8:10:12:15:18 | |

| Forte no. / | |

| 5-27 / |

Notable examples

- In una stanza con poca luce (Ennio Morricone: Once Upon a Time in the West soundtrack no. 18.)

Cmaj9 chord. |

The parallel root-position bop voicings that open the choruses of Thelonious Monk's 1959 Monk's Mood feature a (C) major ninth chord.[12] |

The major ninth chord consists of a major seventh chord and a major ninth. The formula is 1, 3, 5, 7, 9. This chord is written as Cmaj9.

6/9 chord

The 6/9 chord is a pentad with a major triad extended by a sixth and ninth above the root, but no seventh, thus: C6/9 is C,E,G,A,D. It is not a tense chord requiring resolution, and is considered a substitute for the tonic in jazz. The minor 6/9 chord is a minor triad with an added 6th of the Dorian mode and an added 9th, and is also suitable as a minor tonic in jazz.[14]

Heinrich Schenker, though he allowed the substitution of the dominant seventh, leading-tone, and leading tone half-diminished seventh chords, rejected the concept of a ninth chord on the basis that only that on the fifth scale degree (V9) was admitted and that inversion was not allowed of the ninth chord.[15]

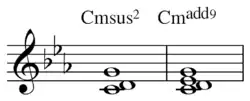

Second

Suspended chord (sus2) and added tone chord (add9) both with D (ninth=second), distinguished by the absence or presence of the third (E♭).[16] |

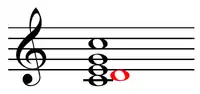

Ninth (D), in red, of a C added ninth chord ( |

In music, the second factor of a chord is the note or pitch two scale degrees above the root or tonal center. When the second is the bass note, or lowest note, of the expressed chord, the chord is in third inversion ![]() Play . However, this is equivalent to a gapped eleventh chord.

Play . However, this is equivalent to a gapped eleventh chord.

Conventionally, the second is third in importance to the root, fifth, and third, being an added tone. It is generally not allowed as the bass note since that inversion resembles an eleventh chord on the second rather than an added tone chord on the original note. In jazz chords and jazz theory, the second is required due to its being an added tone.

The quality of the second may be determined by the scale, or may be indicated. For example, in both a major and minor scale a diatonic second added to the tonic chord is major (C–D–E–G or C–D–E♭–G) while one added to the dominant chord is major or minor (G–A–B–D or G–A♭–B♭–D), respectively.

The second is octave equivalent to the ninth. If one could cut out the note in between the fifth and the ninth and then drop the ninth down an octave to a second, one would have a second chord (C–E–G–B♭D′ minus B♭ = C–D–E–G). The difference between sus2 and add9 is conventionally the absence or presence, respectively, of the third.

Sources

- Sadie, Stanley, ed. (1980). "Ninth chord", p.252, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. 13. ISBN 1-56159-174-2.

- Schoenberg, Arnold (1910). Theory of Harmony, p.346-7. University of California Press. First published in German as Harmonielehre in 1910. ISBN 9780520049444. Roman numeral analysis and arrows not included in the original.

- Benward & Saker (2009). Music in Theory and Practice: Volume II, p.183-84. Eighth Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis, p.85. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

- Benward & Saker (2009), p.179.

- Fétis, François-Joseph and Arlin, Mary I. (1994). Esquisse de l'histoire de l'harmonie, p.139n9. ISBN 978-0-945193-51-7.

- Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis, p.83. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

- http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/features/breakingtherules/images/stimmung.mp3

- Cook, N., A Guide to Musical Analysis, London, J.M.Dent,

- Smith, John (1853). A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Music, p.27. J. McGlashan. [ISBN unspecified].

- Taruskin, R. (2010) The Oxford History of Western Music, Volume 4, Music in the Nineteenth Century, Oxford University Press.

- Walter Everett (Autumn, 2004). "A Royal Scam: The Abstruse and Ironic Bop-Rock Harmony of Steely Dan", p.208-209, Music Theory Spectrum, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 201-235.

- Berg, Shelly (2005). Alfred's Essentials of Jazz Theory, Book 3, p.90. ISBN 978-0-7390-3089-9.

- Jazz Lessons

- Schenker, Heinrich (1980). Harmony, p.190. ISBN 978-0-226-73734-8.

- Hawkins, Stan. "Prince- Harmonic Analysis of 'Anna Stesia'", p.329 and 334n7, Popular Music, Vol. 11, No. 3 (Oct., 1992), pp. 325-335.