Nymphenburg Palace Park

The Nymphenburg Palace Park ranks among the finest and most important examples of garden design in Germany. In combination with the palace buildings, the Grand circle entrance structures and the expansive park landscape form the ensemble of the Nymphenburg Summer Residence of Bavarian dukes and kings, located in the modern Munich Neuhausen-Nymphenburg borough. The site is a Listed Monument, a Protected Landscape and to a great extent a Natura2000 area.[2][3][4][5]

| Nymphenburg Palace Park | |

|---|---|

| Schlosspark Nymphenburg | |

Grand Cascade | |

| |

| Location | Munich, Germany |

| Coordinates | 48°9′28″N 11°29′34″E |

| Area | 229 ha |

| Designer | Agostino Barelli, Friedrich Ludwig Sckell, Charles Carbonet, Dominique Girard, Joseph Effner, François de Cuvilliés |

| Operated by | Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes[1] |

The exquisite composition of formal garden elements and English-style country park is considered a masterpiece of garden design and the spacious complex of palace and park has always been a popular attraction for local residents and tourists alike. To the east the park adjoins the palace buildings and the Grand circle. To the south and west the park is largely enclosed by the original Garden wall and borders the Botanical Garden to the north and beyond Menzinger Straße the park peripherie partly merges with the Kapuzinerhölzl forest.[6][7]

The designs of the original Baroque gardens had largely been modeled on the French gardens at Vaux-le-Vicomte and Versailles. The modern park layout is the result of a fundamental redesign by Friedrich Ludwig Sckell, beginning in 1799. The park area within the Garden wall occupies 180 hectares and the complete complex covers 229 hectares.[8][9]

Overview

The Park is divided into the vast country and landscape park sector in the west and the formal garden sector adjacent to the palace. The Central canal divides the park into a northern and a southern sector. Water is provided by the Würm river in the west (ca. 2 km (1.2 mi)) and transferred to the Park via the Pasing-Nymphenburg Canal and discharges via two canals to the east and northeast and via the Hartmannshofer Bach to the north.[10]

The western landscape park features the smaller Pagodenburg Lake with the Pagodenburg in the northern part and the larger Badenburg Lake with the Apollo Temple and the Badenburg in the south. The Grünes Brunnhaus (Green Pump House), in which the water wheel works and pressure pumps for the park fountains are installed, is situated in the village in the southern part of the park. The Amalienburg occupies a parterre in the southeastern area of the park.

To the east, the Park ends at the palace building. On the garden side of the palace (west) follows the large Garden parterre, which constitutes the central part of the large rectangle surrounded by canals. The Garden parterre flanks the Central (axis) canal. The Grand circle (Schlossrondell) is situated to the east on the city side of the palace.[3]

History

Earliest designs

The 1662 birth of Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria of the Wittelsbach family was the occasion to consider the construction of a palatial residence and garden for the young mother, Electoress Henriette Adelaide of Savoy, in between the villages of Neuhausen and Obermenzing. The foundation stone was laid for the Schwaigbau zu Nymphenburg in 1664. Contrary to a common misconception, the Italian name Borgo delle Ninfe (castle of the nymph) was only created in the 19th century. The initial building was a Lustschloss (pleasure palace) in the tradition of Italian country villas. The elaborate Baroque palace complex, which would serve as a summer residence and alternative to the seat of government, the Munich Residenz, was only realized a generation later under the adult Maximilian II Emanuel. The model for the Lustschloss was the Piedmontese hunting lodge at the Palace of Venaria, whose architect Amedeo di Castellamonte supplied the first designs for the Nymphenburg Palace. Agostino Barelli served as the first architect and Markus Schinnagl was employed as master builder.[11] Work began in 1664 with the construction of a cube-shaped palace building and the creation of an Italian-style Garden parterre to the west.[12]

The French garden

_020.jpg.webp)

From 1701 to 1704 Charles Carbonet altered and extended the garden in the style of the French Baroque. Simultaneously the approximately 2.5 km (1.6 mi) long Pasing-Nymphenburg canal was constructed and connected to the Würm river.[13]

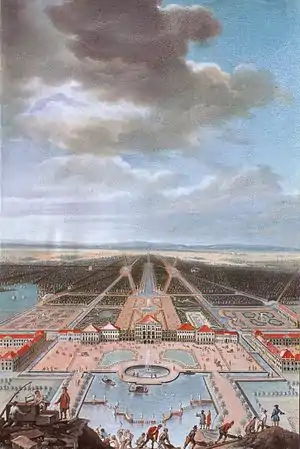

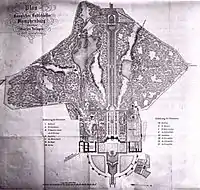

From 1715 onwards Dominique Girard, who had previously worked in André Le Nôtres Versailles Gardens, realized the spacious arrangements of the park with the support of Joseph Effner, a student of Germain Boffrand. Girard managed to skillfully distribute the water in the formerly dry area. A rectangle of canals was built, that formed an island for the main palace and the Garden parterre. The ca. 900 m (3,000 ft) long Central axis canal sector to the west of the rectangle was added, which ends at the Great Cascade, where it was connected to the Pasing-Nymphenburg canal. In the manner of French models roads were laid out in straight lines and rows of trees and arcades were planted, in order to strictly divide the park. The complex now consisted of two main areas, the ornamental garden near the palace and the forest in the west. The park castles sit on independent, small parterres.[14][15][16]

From 1715 on, Maximilian II Emanuel had the forest outside the palace park transformed into a deer hunting range and enlarged to nearly reach Lake Starnberg. On a larger scale, aisles and roads were created and three hunting lodges erected.[17]

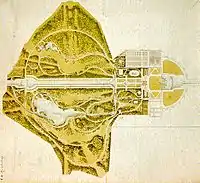

The landscape park

Since 1804 Director of the Royal Gardens, Friedrich Ludwig Sckells redesigns initiated fundamental changes towards the current park design. In 1792 he accomplished the masterful and harmonious combination of the French and English garden style as he had previously at Schwetzingen Palace garden in Baden-Württemberg. However the completion in Nymphenburg took much longer due to the enormous size of the park. From 1799 on, Sckell first designed the secluded Crown Prince's Garden. The work on the spacious landscape park based on the English model began in 1804 with the southern part, which was completed in 1807. The northern part was only completed in 1823.[18][19]

Unlike Lancelot Brown in England, who created extensive landscape parks by destroying the old Baroque gardens, Sckell acted more cautiously. He preserved the parterres on the garden side of the palace as well as the Central axis canal and the Great cascade. He decided to subdivide the park into two distinct landscape areas of varying size, each with its own character and atmosphere, to which two very differently shaped and designed lakes contributed significantly.[20]

Sckell's ploys made Nymphenburg Palace Park a prime example of the synthesis of two fundamentally different garden types. The orderly French Baroque garden, which maintains the idea to enhance nature through the means of art and order flanked by the English landscape park, that highlights the free play of nature. Some areas of the park were first opened to the public in 1792 under Elector Charles Theodore.[8][9]

The park after the fall of the monarchy

Originally, the driveways, the Great circle, the palace and the park constituted a unit that once stretched from east to west over a distance of more than 3 km (1.9 mi) to the west of the city of Munich. The growth of the city admitted the full development of residential areas and road network into the surrounding areas. The construction of the wide Ludwig Ferdinand Bridge over the Nymphenburg Canal, of houses along the northern and southern entrance to the palace and the railway line in the west, completely embedded the park and the palace into the urban structures and thus became a district of the city.[21][22]

With the monarchy abolished, the park and palace became part of the former Krongut (Crown estate), now administered by the state. After the Weimar Republic, the National Socialists seized the complex. Beginning in the summer of 1936, the Night of the Amazons, was regularly performed. After the violent appropriation of the monastery church in the Orangery wing, a hunting museum was opened in this part of the palace in October 1938. The NSDAP local group leadership received an underground bunker and in 1942 established a Forced Labour Camp at the Hirschgarten (Deer Garden), just outside of the park.[22][23]

During the Second World War, the palace and the Amalienburg were camouflaged to protect them from air raids, the large pathways were darkened and sections of the Central canal were covered and the water basins on the city side of the palace leveled. The palace church, the Entrance court, the Badenburg and the Grand Cascade were destroyed or seriously damaged by bombs. The Pan group of sculptures and a number of trees in the park were also damaged. After the war Allied soldiers blew up an old building south of the Great Cascade that had been used as an armory.

The repairs at the palace and the park only proceeded slowly. Although the restoration was carried out according to the historical models, a number of losses could not be restored. The sports ground in the southernmost corner of the park, built before World War II, still represents an ongoing violation of the parks design.

During the 1972 Summer Olympics, equestrian events took place in the palace park: the dressage competitions were held on the Garden parterre. The park's statues were removed, the equestrian arena and grandstands were erected as temporary facilities while adjacent buildings of the palace were used as stables.[9][25][24]

The park and its elements

The Driveways

The northern and southern driveways run alongside the canal that runs from the city to the palace. They are the only part of a star-shaped avenue system planned by Joseph Effner for an ideal Baroque city (Carlstadt). In addition, it was planned to connect the elector's three summer residences (Nymphenburg, Schleissheim Palace and Dachau Palace) with canals. On the one hand the court society could move from one venue to the next with gondolas, and on the other - this provided a convenient transport route for agricultural products and building materials.[26][22]

The very long palace driveways along the palace canal served to display absolutist power. The idea was to impress aristocratic guests: A visitor, who was approaching the palace from the east in a horse-drawn carriage, noticed the growing building backdrop. When driving through the Grand circle his vehicle described a semicircle, so that the extra-wide palace front presented all its grandeur.[27][22]

The palace and the Grand circle

The end point of the palace canal leading from the city to the palace is the Ehrenhof. Effner designed its center as a water parterre, with fountain, water cascade and canals branching off on both sides. These canals break the string of main palace elements and annex buildings and continue under the galleries (built from 1739 to 1747) on the garden side. This further emphasized the connection between the Cour d'honneur, the palace and the gardens in the background, also denoted by large window openings and archways in the main building.

The Grand circle on the city side ends at the Cavalier houses, a semicircle of smaller buildings. These ten circular pavilions were planned by Joseph Effner and built after 1728. Since 1761, the Nymphenburg Porcelain Manufactory has been located at the Nördliche Schloßrondell 8, a two-storey hipped roof building with a semicircular risalit center and structured plaster. During the baroque period the Orangery was located in the square building at the northernmost corner of the palace. The Carl Friedrich von Siemens Foundation is located at Südschloßrondell 23, a two-storey baroque hipped roof building with structured stucco and a narrow central risalit, erected in 1729 by Effner. In front of the Ehrenhof (Cour d'honneur) is a Lawn parterre, which underlines the design concept of the palace garden.[8]

The Garden parterre

The Garden parterre, closely linked to the garden side of the palace, still remains a visible feature of the French garden. In the course of the redesign of the entire palace park by Sckell, it was simplified, but retained its original size: in 1815, the six-part broderie parterre became a four-part lawn with a flower bordure. The view of the observer standing on the palace stairways is being lead across the parterre with the fountain to the central water axis.

Today, the parterre is divided into four fields, of which the eastern ones facing the palace are significantly longer than the western ones. This shortening of perspective creates additional depth of space when seen from the palace staircases. The effect is enhanced by the central fountain. The parterre has a lawn like a parterre à l'angloise (lawn compartments), bordered by a surrounding row of flowers. Spring and summer flower plantings with variations in color are usually applied.[28]

The landscape park

The largest area of the park is occupied by the English-style landscape garden. The northern part is defined by panoramic vistas of the Pagodenburg Lake with the Pagodenburg and the Pagodenburg valley, A meadow valley is running to the north with a brook, that flows into the Kugelweiher pond. The southern part is even more diverse with a panoramic vista of the large Badenburg Lake, It allows visitors views of the water surface at the Apollo temple (built in the form of a monopteros) and the Badenburg, behind which a wide meadow valley, called the Löwental (Lion Valley) leads to the south, as well as to a hamlet, the Amalienburg and the Crown Prince Garden south of the Great Parterre.[9][28]

Crown Prince’s Garden

The rectangular Crown Prince’s Garden (Ludwigsgarten) is located northeast of the Amalienburg. It was the first work of Friedrich Ludwig Sckell in Nymphenburg. He created this moderate garden, which already had some characteristics of the English garden style for the young Ludwig I in 1799. The pavilion, a two-storey wooden structure, was also built for him. Its octagonal main part has two rooms on two floors with the same layout. In the portico, which is popularly called the Witch's house, a staircase leads to the first floor. Its exterior painting is intended to give the impression of an artificial ruin. The walls inside are decorated with hand-printed wallpaper. A small brook emerges from between stones as if from a natural rock spring. It is fed from the water of the southern canal via a gradient water pipe. The garden is separated from the rest of the Amalienburg garden by a wooden fence. The Crown Prince's Garden was restored in 1982/83.

The Decor gardens

There are three decorative gardens north of the Garden parterre. They adjoin the old greenhouses to which they are spatially related. These flower gardens were designed between 1810 and 1820 by Friedrich Ludwig Sckell as formal, regular structures which were supposed to contrast with the landscape park.

North Cabinet Garden

This small garden is directly adjacent to the garden side of the north wing of the main palace. It is also called the Kaisergarten (Imperial Garden) because it is located in the immediate vicinity of Prince-elector Karl Albrecht's apartment rooms, where he resided during his time as Charles VII (Holy Roman Emperor from 1742–45). Its counterpart lies in the South Cabinet Garden. Both are giardini segreti (secret gardens), that provided privacy, retreat and relaxation. The concept has its origins in 15th and 16th century Renaissance northern Italy.[29]

One of its elements was a parterre of flowers, an arbor, that lead to a garden pavilion to the north, in front of which is a round, now dried out water basin, to which leads a staircase. Two parallel beech hedges lead from north to south, each with five niches adorned with Hermes busts on bases. The busts are made of coarse-grained marble, the bases are made of red marble. They may have been made in the late 17th or early 18th century in Giuseppe Volpini's workshop.

The North Cabinet Garden is one of the oldest, still structurally preserved elements of the Nymphenburg park.

South Cabinet Garden

The South Cabinet Garden resembled the North Cabinet Garden before it was redesigned by Friedrich Ludwig Sckell. Sckell adorned it particularly rich with precious woody plants. The Small Cascade, that consists of two basins is situated in the south corner. Its current form probably dates back to a 1764 design by François Cuvilliés and might have been built in 1724 when this section of the garden was created. The upper, smaller pool is adorned by a Nappe d'eau (water blanket). Both pools are made of red marble. An Aedicula was added behind the upper basin - most likely in the early 19th century - that featured a copy of Antonio Canova's Venus Italica in the niche.

The Small Cascade is surrounded by four Konrad Eberhard still images. They depict Leda with the swan (1810), Silen (a satyr) with Bacchus as a boy (1812), the sleeping Endymion (1820) and Diana hurrying towards him (1820). The sculptures on display are copies, whose originals had been made from Carrara marble. The octagonal bird house, created by François de Cuvilliés in 1757 is placed in the northern part of the garden. The building - a small garden pavilion - is executed in stone and plastered on all sides. A protruding, cage-like grating, made of wrought iron is fixed to the front of the southern window. The building is also a Cuvilliés creation. The vivid paintings are the work of Ambrosius Hörmannstorfer (restored in 1977 by Res Koller).

The restoration of the Cascade was completed in July 2008. Originally controlled by a gradient water pipe from the canal at the Green Pump House, operation was upgraded to a circulation system with a pump and filter. The stones of the former well edgings were reused, new sculptures were cast from the originals images.

Lakes and the canal system

The barely perceptible height difference of about 5 m (16 ft) between the northern and southern plots of the park, allowed the creation of three levels by skillful water management. The sloping terrain permitted the cascades and the operation of water wheels for pumping purposes. The water is conveyed from the Würm river near Pasing to the west and transferred into the park area via the Pasing-Nymphenburg Canal. The canal that branches off into the southern, higher part of the park maintains its original level, while the bulk of the water feeds the Grand Cascade. A bypass canal in the north provides additional water to the pool below the cascade. The cascade and the bypass canal fall to the lower level of the Central canal and the water basin in front of the Garden parterre. The northern bypass was originally connected by a sluice to the canal that comes from the west. The sluice has been replaced by a small weir.

Some of the water in the southern canal is used to operate the water wheel pumps for the garden-side fountain, the rest flows through a waterfall (former sluice) to the lower level of the Central canal. The Central canal is divided into two arms in front of the large parterre, which run under the connecting wings of the palace (therefore called "water passages"), encompass the main palace building and Garden parterre and then lead to the pool in front of the courtyard. The pumping station in the St John’s Pumping Tower of the palace building, which is also driven by water wheels, is fed from the northern arm. The majority of the park's water then falls back to the lower level of the basin of the Grand circle and the palace canal between the palace driveways, which ends in a water basin (Hubertusbrunnen). However, the water is not drained through the palace canal, but through two inconspicuous canals in the northern quarter of the Grand circle, which are actually the beginning of the Nymphenburg-Biedersteiner Canal.[22]

The Lakes

The two lakes have a significant impact on the Nymphenburg Park. These artificial waters were created in the course of the redesign by Ludwig von Sckell. There already existed two small ponds during the Baroque period that were related to the Parkschlösschen Badenburg and Pagodenburg. Sckell thus followed an existing idea. The excavation provided the material for the meadow valleys.

Badenburg Lake

The larger of the two lakes, the Badenburg Lake is located in the southern part. It owes its name to the Badenburg at its southern bank. It was created between 1805 and 1807 on an area of 5.7 hectares. An Apollo temple in the form of a monopteros is positioned on a headland in the north. It dominates the northwestern lake and is clearly visible from various places on the shore. There are three small islands in the lake.

Pagodenburg Lake

Situated in the northern sector is the smaller lake, the Pagodenburg Lake. It was completed in 1813. The Pagodenburg, which lies on an island formed by a ring-like canal, dominates the design and largely occupies the northern part of the lake and can be reached via two pedestrian bridges. The area of the lake including an approximately one hectare island stretches over 2.9 hectares. The lake feeds the Hartmannshof Brook, which gently flows north through the rolling hills of the Pagodenburg Valley and flows 420 m (1,380 ft) further north into the Kugelweiher pond - a creation typical of Sckell. The water inlet of the lake from the Central canal is underground and was originally disguised as a rock grotto. A dam overgrown with thick hedges shields the lake to the south from the higher Central canal.

Canals, locks and bridges

The canals of the palace park belong to the Nymphenburg Canal, which widely traverses large swaths of Munich's West. While the Central canal is reminiscent of French gardens, the entire system is based on Dutch models, in particular on Het Loo Palace. Most canals were navigable by boat until 1846. Remnants of the 18th century locks and sluices are located at the flooding canal behind the Great Cascade and between the Village and Amalienburg in the southern park canal.

Once there existed sixteen flap bridges in the park, however the currently existing concrete bridges date from recent times (Nymphenbrücke 1902, Bogenbrücke 1903, Badenburgbrücke 1906, Northern and Southern Schwanenbrücke 1969), they are decorated and have wrought-iron railings. As the bridges cannot be opened, navigation of boats and gondolas is no longer possible. The Ludwig-Ferdinand-Brücke spans the Central canal in front of the Grand circle since 1892. Eventually it was upgraded for tram use.

The Central canal

The central water axis dates back to the original Baroque design of the garden. The Central canal begins at a basin below the Great Cascade, runs 800 m (2,600 ft) straight to the east and ends in another basin that closes the Garden parterre. Two canals branch off from this water basin and flow around the Garden parterre with the flower gardens and the greenhouses in the north and a strip of the Amalienburg sector of the park in the south and then flow to the east towards the palace. Both canals pass underneath the wing buildings of the palace.[21]

The southern canal

The western part of the southern canal feeds Lake Badenburg. Apart from the small amount of water that drains via the small stream near the Pan sculptures, the canal extension diverts the waters of the lake towards the east. During the Baroque period it served as a small waterway. Gondolas and boats navigated here in the service of members of the court. The small watercraft used a sluice to overcome the difference in height between Lake Badenburg and the central basin on the Garden parterre.[21]

Fountains and water works

The ingenious and crafty use of water imparts the Nymphenburg system its charming liveliness. Water appears in the form of the calm surfaces of the two lakes, flows in canals and streams, falls and rushes in the two cascades and rises in the geysers of the two large fountains. However, the numerous water works of the Baroque period are no longer available.

The Great Cascade

All the water that flows through the park must be transferred in from the west via the Pasing-Nymphenburg Canal. A considerable part of the water falls at the Great Cascade from the upper to the lower cascade basin. The cascade forms the end point of the visual axis along the Central canal, although it is hardly recognizable from the palace staircases due to the considerable distance.

Some of the remaining water of the Pasing-Nymphenburg Canal is being channeled into the southern canal before the cascade while maintaining its level, the rest falls into a lateral flooding canal of a former sluice and supports the feeding of the Central canal.

The fountains in front of the palace and on the garden side

The fountains are still operated by pumping stations that are driven by water wheels and have been in operation since the beginning of the 19th century.

The city-side fountain receives its water from the pressure pumps in the St John’s Pumping Tower (Johannis-Brunnturm) of the palace building, which are driven by three colossal water wheels. On elector Maximilian I Josephs order in 1802 Joseph von Baader redesigned and in 1807 eventually replaced the pump that had been built by Franz Ferdinand Albert Graf von Wahl in 1716. The facility largely retains its original condition.[30][31]

The garden-side fountain had its predecessor in the Flora-fountain, which dominated the Baroque garden parterre. It was built from 1717 to 1722. Its large, octagonal marble basin was adorned with numerous figures made of gold-plated lead by Guillielmus de Grof. In addition to the large statue of Flora, putti and animal figures once existed, some of which were arranged in teasing positions. The fountain was demolished at the beginning of the 19th century due to the simplification of the Garden parterre by Ludwig von Sckell, its remains have since disappeared. Today's fountain is operated by a pressure line from the Green Pump House in the village.[32][31]

Architecture

The park castles

The so-called park castles (Parkschlösschen) are not mere decorative buildings, but pleasure palaces (Lustschlösser) with comfortable rooms, many of whom represent architectural gems. The Pagodenburg is located at the smaller, northern Pagodenburg Lake. The Badenburg is located at the larger, southern Lake Badenburg. The Amalienburg, the largest of the Parkschlösschen, is the center of a rectangular garden section, that borders the Garden parterre to the south.

Badenburg

The Badenburg is located at the southeastern end of the Great Lake. The structure dominates parts of the lake, as it smoothly sits into a visual axis where it can also be seen from the north. The castle was built by Joseph Effner from 1718 to 1722. For centuries it was the first large building in Europe that was used solely for the purpose of enjoying a comfortable bath.[33] As part of the restoration from 1983–84, the wooden shingle roof and the ocher-yellow coloring of the building were restored.

Two outdoor staircases, one from the south and one from the north, lead into the building. The northern one opens the spacious hall to the lake. Further rooms on the ground floor are: the bathroom to the south-west, the bedroom with adjoining writing cabinet and warderobe to the south-east and a central gambling room with access to the hall. The hall features festive decorations by Charles Dubut. The ceiling fresco of Jacopo Amigoni, destroyed in 1944, was replaced in 1984 by a copy of Karl Manninger. Three rooms are decorated with Chinese wallpaper. While two of them show scenes from far-eastern everyday life, the third shows plants, birds and butterflies in pink and green colors. In the large hall there are two fountains with statuettes of Tritons children riding on water-spouting dolphins, the gold-plated, hollow lead castings are works of Guillielmus de Grof (1722).

The bathroom extends over two floors - basement and ground floor. It is almost completely occupied by the swimming pool, which has been called luxurious with a lavish area of 8.70 m × 6.10 m (28.5 ft × 20.0 ft) and a depth of 1.45 m (4.8 ft). It is covered with Dutch tiles. The gallery, covered with stucco marble, is enclosed by a wrought-iron railing by Antoine Motté. Nymphs and naiads adorn the ceiling of the bathing room. The technical systems required for water heating are located in the basement.

The southern staircase is flanked by two lion figures, which were probably erected on the front sides around 1769. They were made by Charles de Groff and consist of Regensburg Green Sandstone. The stairs link the castle with a wide meadow valley, the Löwental (lions valley).[34][35]

Pagodenburg

The Pagodenburg (pagoda castle) was built as a maison de plaisance under the direction of Joseph Effner from 1716 to 1719, by allegedly using a floor plan of Max Emanuel. In 1767 François Cuvilliés (the Older) undertook a reconstruction in the Rococo style.[36]

The term Pagodenburg (pagoda castle) has already been used in contemporary reports and refers to the interior fashion of the Chinoiserie. At that time, the term pagoda meant both, the pagan temples in Asia and the gods depicted in them. The latter can also be found in the wall paintings on the parterre of the Pagodenburg.

The two-storey building is octagonal and has a cross-shaped, north–south-oriented floor plan thanks to four very short wings.

The ground floor consists of a single room, the Salettl, all in blue and white. Its walls are largely covered with Delft tiles. The niches and the flanks of the side cabinets, as well as the door to the staircase are covered with murals by Johann Anton Gumpp, that show numerous Asian gods. The ceiling is adorned with paintings of female personifications of four continents.[37]

Around 1770 the original furnishing of the Salettl was replaced by Rococo-style furniture, which with its blue and white framing picks up on the colors of the wall design and can still be seen in the Pagodenburg. This includes a round extendable table with the Wittelsbacher coat of arms on top, two canapes and a chandelier.[38]

The upper floor of the Pagodenburg is divided into four sections. While one wing is reserved for the staircase, the other three house the relaxation room, the Chinese salon and the smaller Chinese cabinet. The relaxation room is the only room in the Pagodenburg without any elements of Chinese fashion, but is entirely committed to the style of French Régence. There is a fireplace with a mirror above it, and an alcove with two beds.

The walls of the Chinese salon are clad in black lacquered wood paneling, which serves as a frame for Chinese scroll paintings with plant and bird motifs. There are European lacquer panels in the window and door reveals, which are also painted with floral motifs based on the scroll paintings. Above is a golden figure frieze, which leads the viewer to the ceiling painting which also shows Chinoise motifs in a grotesque style. The Chinese cabinet has the same basic structure as the Chinese salon, but the wall paneling is in red lacquer. The total of 33 scroll paintings that were used for the wall paneling on the upper floor are New Year pictures imported from China, only three of which are European imitations.

The two lacquer chests of drawers in the Chinese salon were assembled in France from East Asian lacquer panels. The fronts and the cover plates show Urushi paintwork with golden and silver scatter patterns and paintings on a black background. Cranes, ducks and swans can be seen on a riverside landscape.

In 2003 a comprehensive restoration of the Pagodenburg was completed.

A replica of the Pagodenburg is located in Rastatt. Margravine Franziska Sibylla Augusta of Baden was so impressed during a visit to Elector Maximilian II Emanuel that she had the plans sent to Rastatt. The Rastatt Pagodenburg was built there under the direction of court architect Johann Michael Ludwig Rohrer.[39][40]

Amalienburg

The Amalienburg is located in the Amalienburg garden, which adjoins the garden parterre to the south. It was designed by François Cuvilliés (the Older) and built from 1734 to 1739 as a hunting lodge for pheasant hunting. Although the Rocaille is the leading form in the ornamentation of early Rococo, floral ornament motifs still predominate in the building.

In front of the entrance in the west is a curved courtyard. A staircase leads to the outside on the eastern side. Originally there was a garden parterre related to the building, which due to the later redesign of the landscape style is no longer recognizable.

The one-story Rococo building was a gift from Elector Karl Albrecht to his wife Amalie. The stucco work and carvings of the hunting lodge were carried out by Johann Baptist Zimmermann and Joachim Dietrich. The entrance leads to the centrally located, round mirror hall, the mirror walls of which reflect the external nature. In the north are the hunting room and the pheasant room, in the south the rest room and the blue cabinet; the retirade and the dog chamber are accessible from there. The kitchen borders the pheasant room in the north. The blue and white Chinese-style tiles show flowers and birds. A kitchen by François Cuvilliés (the Older) featured a Castrol stove (derived from the French word Casserole - saucepan). It was the first stove with a closed fire box and a hotplate above (see also Kitchen stove). As the rooms were particularly rarely used in the princely environment, the kitchen and hunting room underwent a final comprehensive renovation only at the 800th anniversary of the city of Munich in 1958.[41][42]

In the middle niche of the eastern facade sits a stucco semi-sculpture by Johann Baptist Zimmermann, which depicts a scene with the hunting goddess Diana. This presentation introduces the image idea for all accessories of the building. The attic carried decorative vases from 1737, also made according to a design by Zimmermann, which disappeared at an unknown time. They were recreated in 1992 according to a design by Hans Geiger, four adorn the entrance facade since and twelve are placed in the garden side of the Amalienburg.

A platform with an artistic lattice, which is placed on the building in the middle of the roof, served as a high stand for the pheasant hunt. The birds were driven to the Amalienburg by the then pheasantry (now the menagerie building). Since the castle could be supplied by the kitchen of the palace, the Amalienburg, unlike the other two park castles, did not require a service building.[43][44]

Magdalenenklause

Although it is considered one of the park castles, the Magdalenenklause, which is somewhat hidden in the northern part of the park, differs significantly from the other castles. It was built by Joseph Effner between 1725 and 1728 and is a hermitage, designed as an artificial ruin. The single-storey building has a rectangular floor plan, the aspect ratio of which corresponds to the golden ratio. The rectangle is expanded to the northwest and southwest by two apses and two small, round extensions are attached to the corners of the building at the front. The entrance facade alludes to Italian ruins, the plastering on the outside reveals seemingly bricked-up window openings, which reinforces the impression of the deteriorated condition. The roof, which was kept flat until 1750, suited this as well.

The building is considered an early representation of Hermitage and Ruin architecture in Germany. The location, separated from the neighboring castle, was to serve the Elector Max Emanuel as a place of contemplation - a memento mori, the completion of which the Elector not lived long enough to see.

The building is entered from the east. Following a vestibule, an ante-room and a small cabinet, is a dining room and a prayer room. A contrast to these rooms, which are plainly furnished with simple paneling, exhibits the two-part chapel, the walls of which are grottoed with fantastic stucco work, shells and originally colored pebbles. The design was executed by Johann Bernhard Joch, the stucco figure of the Penitent Magdalene is the work of Giuseppe Volpini, the ceiling frescoes in the chapel room and in the apse were created by Nikolaus Gottfried Stuber. The grids were crafted by Antoine Motté.[45]

Temple of Apollo

The Apollo temple stands on a peninsula on the shore of Lake Badenburg. It is a monopteros with ten Corinthian-style columns made of grayish beige sandstone. The building was erected by Carl Mühlthaler (1862–65) according to a plan by Leo von Klenze. Inside is a marble stele dedicated to king Ludwig I. The temple is one of the landmarks of the lake's surroundings, invites to rest and allows the visitor a panoramic view over the water surface.

Prior to the marble temple, two round wooden structures stood on the headland. The first was built at the 1805 birthday of the elector. As it had become derelict, Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell proposed the construction of a circular stone temple with a cella based on the Vesta temple in Tivoli. After the idea was rejected, a somewhat larger replacement building made of larch wood was built and completed in 1818.

The Village

The five buildings of The Village are situated on the north bank of the southern park canal. The houses, built for court officials near a beaver enclosure that no longer exists today, are still partially inhabited. They embodied the idealized idea of country life in early modern times and the longing for the supposed idyll of the world of farmers and shepherds. Models for the design can be found in the decorative village of the Chantilly park (1774) and in the Hameau de la Reine in the Versailles Palace park (1783).

In the second half of the 18th century, the two-story Green Pump House was joined by a few more small single-storey farmhouses. These are the Deer Park Pump House, the Brunnwärterhaus, formerly with a smithy, and the former Biberwärterhaus. In 1803/04 the pump house, which had previously been accompanied by two wooden water towers, was converted into the Green Pump House. Its pressure pumps since operate via internal water wheels. Water is led into the building via a small branch from the southern canal, which at this point is still at the level of the Würm Canal. As the doors and windows are open during the day, the visitor can observe how the height difference of the site is utilized for energy generation. The machines were designed by Joseph von Baader in 1803 and have been supplying the fountain on the Garden parterre ever since.[20][46][31]

The historic greenhouses

The greenhouses of the Nymphenburg Park, not to be confused with those of the nearby botanical garden, are adjacent to the three flower gardens in the north. They are arranged in one line, parallel to the floor plan of the Garden parterre on the inside and the canal rectangle on the outside. The eastern greenhouse was built in 1807 and rebuilt after a fire by Carl Mühlthaler in 1867 as an iron and glass structure. It is since called the Iron House. The rooms under the roof served as living space for the gardeners, who were ordered to maintain constant temperatures around the clock. Thus under glass cultivation of delicate exotic plants was possible by the enthusiastic botany collector king Maximilian I Joseph. The middle greenhouse is the Geranium House that Sckell had constructed in 1816. The side pavilions built as wing structures were used by Maximilian I Joseph and his family at their visits. To the west is the Palm House that Sckell had built in 1820. Hot water heating was installed in 1830.[47]

The Schwanenhals Greenhouse is located to the north, right on the palace wall. It is the oldest structure in the area. Built in 1755, rare fruits, such as pineapples were grown here for the court kitchen.

Menagerie

The site of the former menagerie is located outside the Park wall south of the Amalienburg garden. King Maximilian I Joseph has acquired a large number of exotic animals, including a llama, kangaroos, a monkey and various types of birds.

Sculpture program

The image concept of the park, established in the 18th century, embraces Greco-Roman mythology. The sculptures represent deities and characters of both, Greek and Roman pantheons and myth. Their arrangement was changed during the establishment of the English landscape park. Today only twelve statues remain on the Garden parterre and four have been moved to the Grand Cascade. Generally male and female deities take turns. Most of the statues are made from Laaser and Sterzinger marble, the bases are made of Red Tegernsee marble or tuff.

The image concept of the Baroque garden has once been considerably more extensive than today's garden furnishings would suggest. Statues and decorative vases, made of gilded lead and twelve vases, made by Guillielmus de Grof from 1717 to 1722 once dotted the parterre. The paths on the Great Cascade were also decorated with a group of fourteen statues made of lead by Guillielmus de Grof, twelve Cherubs represented the months of the year, two others the continents. They were repaired in 1753–54 by Charles de Groff, son of Guillielmus Groff, and placed on the Garden parterre. However, none of the lead statues and vases have survived. They were considered unfashionable by the end of the 18th century and removed, when weathered from exposure, cracked, parts broken off, their iron supports rusted away or fallen from their bases.

The furnishing with marble statues was an extremely slow process as provisional stucco models lasted for many years. The first designs for the modern marble statues were provided by Franz Ignaz Günther, Johann Baptist Hagenauer and Johann Baptist Straub. Researchers, however, disagree on the exact artist/work attribution.[48][49]

Statues on the Garden parterre

There are two types of sculptural decoration on the Garden parterre, twelve large statues on plinths and twelve pedestal decorative vases with figural reliefs, all in the form of a series of Cherubs, matching the mythological theme of the statues.

While the vases are set up on the narrow sides of the four compartments forming the Garden parterre, the statues are placed on their long sides. Viewed from the palace garden staircase, on the far left are: Mercury, Venus and Bacchus on the far right are: Diana, Apollo and Ceres and facing each other on the central road: Cybele and Saturn, Jupiter and Juno and Proserpina and Pluto.

Sculptor Roman Anton Boos created all decorative vases (1785-1798) and the sculptures of Bacchus (1782), Mercury (1778), Apollo (1785), Venus (1778), Diana (1785) and Ceres (1782). Dominik Auliczek made the statues of Proserpina (1778), Juno (1791–92), Pluto (1778) and Jupiter (1791–92). The statues of Saturn and Kybele were created by Giovanni Marchiori (both delivered from Treviso in 1765, signed on the plinth) and made of Carrara marble.[50]

The older sculptures of Cybele and Saturn differ in style from the later designs. The hard facial features of Cybele, whose head adorns a mural crown and the drastic pose of Saturn, about to devour one of his sons, convey destruction and cruelty, which is surprising in the context of a princely pleasure garden.

Statues at the Great Cascade

Between the upper and lower cascade basins are two reclining figures with urns on both sides of the falling water, that symbolize the Isar and Danube rivers, made by Giuseppe Volpini (1715–1717). Eight still images on pedestals are grouped symmetrically around the upper basin. These are: Hercules (1718–1721), Minerva (1722–1723), Flora and Aeolus (both around 1728), also from Giuseppe Volpini, Mars and Pallas (both around 1777) and Amphitrite with a dolphin (1775) from Roman Anton Boos and Neptune made by Guillaume de Grof (around 1737). The river gods have been modeled from those in the Versailles Palace park. The sculptures of Volpini had originally stood in the garden of Schleissheim Palace.[51]

The Pan Group

On the way from the Badenburg to the north stands the sculpture of the resting Pan, playing his flute, accompanied by a billy goat. The seated sculpture was made in 1815 by Peter Simon Lamine, who repeats his own motif from 1774 at the Schwetzingen Palace Park.[52] Executed in Carrara marble, the god stands somewhat remote on an artificial elevation on a base made of Conglomerate. The entire surroundings were originally structured with rocks, that have sunken into the terrain. The Pan Monument, as early historians called the group, features an artificial well. It is the outflow of the Great Lake, which drains via a small waterfall into the Teufelsbach, that flows in a northeasterly direction. The background of the ancient mythical figure is formed by yew trees, which merge into the remaining vegetation of barberries, forest vines, blackberries and ferns. It is the only garden suite that was realized during von Sckell's time. Pan depictions are among the popular motifs in 19th century garden sculpture art concepts.

Statues in the Flower gardens

In front of the Iron House, placed in the middle of a round fountain basin, is the statue of a boy, who is being pulled down by a dolphin. It was made from sandstone in 1816 by Peter Simon Lamine at the behest of Maximilian I Joseph. The portrayal of the dolphin as a fish-like monster was common then.

A similar fountain is placed in front of the Geranium house. It also features the body of a boy riding a dolphin in the middle. The sculpture was made by Johann Nepomuk Haller based on a design by Lamine (1818).

A group of four statues on a common base decorates the central flower gardens. It depicts the Judgement of Paris. The statues show Paris with the apple as the subject of the argument, Aphrodite, Hera and Pallas Athena (from left to right), all executed in sandstone by Landolin Ohmacht (1804-1807).[53][54]

The staging of the landscape

The Road network

An elaborate system of roads and footpaths runs through the park. It allows long walks without having to walk twice. All paths are water-bound and there are no adjacent driveways as in the Englischer Garten.

On the large parterre and in the flower gardens, the path network corresponds to the straight lines of the French garden: from the plaza covered with fine gravel in front of the garden-side palace staircase, an extensive connection leads to the garden fountain and on to the westernmost basin of the Central canal, There the visitor moves on to the large east–west axis, with the central building of the palace at the center. To the north and south there are two parallel paths, both with benches, a row of trees and hedges. Parallel paths then accompany the Central canal to the lower basin of the Great Cascade. Both basins are trapezoidal and rectangularly enclosed by paths. The sector of geometric connections ends there.

In the southern garden section of the Amalienburg and the entire landscape park are only paths that in a variety of curves form a greater network with an irregular floor plan. It conveys a feeling of informal movement in a landscape that represents a separate, self-contained cosmos in order to detach the visitor from the everyday world. A significant proportion of the paths leads through forest, the edge of which is designed in many places in such a way that it does not always reach the path, which was a typical design principle of Friedrich Ludwig Sckell. The route system created by Sckell has hardly been changed to date. It is the key to experiencing the landscape of the Nymphenburg Park.

The Garden wall

The forested area of the Baroque garden used to be part of an extensive forest that reached into the Starnberg area and of which only remnants are preserved. The Kapuzinerhölzl forest follows to the north. The Garden wall was erected between 1730 and 1735 to prevent the intrusion of game animals. It almost completely surrounds the entire park except for the Pasing-Nymphenburg Canal, which is separated by a grille, and the east side, which is delimited by the palace building. The wall is roughly plastered and there remains a now non-functional round tower at two of the western corners. On the inside runs a footpath along the wall. This path offers an interesting alternative far from the hustle and bustle of tourism, since this path shows the palace park from its unkept side. The path, that can't be found on official maps has a total length of 7 km (4.3 mi).

The ha-has

The peculiar term ha-ha, also a-ha, used for a lowered wall or for a ditch that replaces a section of a garden wall relates to the visitor's surprise expression: "a-ha" when they discover the visual trick to expand the garden. The term ha-ha was introduced to gardening in the early 18th century and its construction method was described by Antoine-Joseph Dézallier d’Argenville.

Inside the Nymphenburg Park are four ha-has, three large and a smaller one, as three are in the southern part of the park. They extend the visibility through the meadow valleys to the surrounding area. All ha-has were created in the course of the transformation into a landscape park by Sckell. The southern panorama vista ends in the Pasinger Ha-Ha, that dates from 1807. The Löwental (Lion Valley) leads to the Löwental Ha-Ha and the Wiesental towards Laim and the Laimer Ha-Ha, both date from 1810. The Menzinger Ha-Ha ends the Northern panorama vista in the northern part of the park. Originally, distant vistas were possible up to Blutenburg Castle, to Pipping and the Alps. Today, these visual axes are partially obstructed.

The Vistas

A special attraction are the long visual aisles, which can be seen from the garden-side palace stairs and invite to calm views and light experiences, shadows and color nuances depending on the time of day and season. The west-facing central axis leads the eye along the canal to the distant cascade, over which the sunset can be observed on summer evenings, which Friedrich Ludwig Sckell left when he transformed it into a landscape park. To the right and left of the central axis, two symmetrical visual aisles lead into the park landscape and convey an illusion of infinity. In the opposite direction, both aisles acquire the central part of the palace as their focus. These three lines of sight, already present in the French garden, were integrated into the landscape park by Sckell, yet also extended beyond the park boundaries via the ha-has.[20]

North Vista

The North Vista consists of a lawn lane towards the west-north-west with an irregular tree fringe. It begins at the basin of the Central canal west of the Garden parterre. The swath leads the view over almost the entire water surface of the Pagodenburg Lake. A ha-ha extends the view over the park boundary into the adjacent green area.

South Vista

The South Vista consists of a lawn path towards the west-south-west as it also begins at the basin of the Central canal, but continues to open and leads over the northern tip of the larger Badenburg Lake. On the west bank of the lake, the visual aisle is led as a narrow lawn band to the park boundary, where it is also extended by a ha-ha.[20]

Flora and fauna of the Nymphenburg Palace Park

The original landscape design concept of Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell centered around domestic tree species and the woods of the local oak-hornbeam forest with among oak and hornbeam include ash, sycamore - and Norway maple, winter and summer lindens, as well as occasional pines and spruces. Sckell resorted to selective planting methods of differently sized and mixed species in order to acquire effects e.g. for varied and realistic forest silhouettes in front of meadows and the waters. To create atmosphere or add nuances to particular places, von Sckell planted large, small, slender or wide, fast- or slow-growing tree and shrub species in groups, rows or clusters. In the northern park sector he planted: linden trees (at the Pagodenburg), that transitioned into a thicket of dense mixed forest to the north. In the southern sector he planted: also linden trees (near the Badenburg), alder trees (on the Badenburg Lake islands), silver poplars and towering Italian poplars (along the north shore of the Badenburg Lake), robinia trees (at the Temple of Apollo). Rowan berries and dogwood are still occasionally found. Oak trees once stood at the Magdalenenklause and Sckell had the Amalienburg enclaved in a spruce grove, occasional trees of life and Virginian juniper.[55]

Forests

The park forests are rich in species that are well blended and amounted, even according to age. The shrub and hedge layer is not very pronounced and largely limited to a few rows alongside some paths and widely scattered individual shrubs. Typical are hazel, hawthorn, dogwood, privet, honeysuckle, snowball and elderberry in lighter locations. The herb layer is well developed. Hedge woundwort, Aposeris, yellow archangel, sanicle, wood avens and false-brome are found in the shade. In more open areas the wood bluegrass can be found and on the forest fringes grows the rare yellow star-of-Bethlehem. Ivy is widespread. Mistletoe is common on linden trees.

Adaptive tree species have formed riparian forest habitats in ravines, depressions, trenches and canals, where in addition to oak and hornbeam, ash and alder do occur. The bird cherry also grows among them. Unlike in most park forests, among a dense undergrowth are moisture-indicating perennials like cabbage thistle and gypsywort. Bonesets and Filipendula grow right by the lake banks.

During the 1799 redesign works, Sckell incorporated many of the former Baroque garden's old trees into the landscape park. The age-old, hollowed-out, but still vital linden tree near the Hartmannshofer Gate (northwest) has survived to this day.[55]

Meadows and waters

Apart from the lawns on the Garden parterre, all of the park meadows are unfertilized and mown only once a year. On the long and unsheltered meadows of the vistas thrives the Salvia plant family, the main type of which is the false oat-grass. The meadow sage, the brown knapweed, burclover, oxlip, daisy, eyebright and germander speedwell are among the flowering plants of the park meadows. On small, particularly nutrient-poor areas, that combined cover around one hectare, lime-poor grassland has prevailed. It consists of erect brome and heath false brome with bulbous buttercup, large-flowered selfheal, clustered bellflower and sunflower as character types. This is also where the keeled garlic grows, a dry grassland plant classified as endangered on the IUCN Red List for both Bavaria and Germany.

The park's lakes are emptied once a year, which prevents vegetation from forming in the water, and are almost entirely enclosed by artificial banks. An exception is the Kugelweiher pond, a natural water with natural banks, flanked by a 0.5 to 2.0 m (1.6 to 6.6 ft) wide skirt of lesser pond-sedge. There also are found the common skullcap and gypsywort as well as water lilies on the pond surface. The northern section of the inlet to the pond is lined with sedges and tall bushes. Numerous water birds such as the mute swan, geese and ducks as well as the carp in the lakes benefit from intensive feeding by park visitors. However, the high nutrient input affects the water quality.

Ecological value and nature conservation

The Nymphenburg Park with its diverse landscape elements offers, in addition to its cultural inheritance and recreational function, a habitat for many plant and animal species. Seventeen species of mammals and 175 species of birds have been identified. It derives special value from the large size and the original habitat stratification. The pristine mixed woodlands and the many very old trees are also worth mentioning. Particularly valuable is the coarse woody debris that provides nutrient cycling nesting grounds and microhabitats for invertebrates and deadwood inhabitants. Deer have been living in the park since it was a royal hunting ground. Other mammals include the fox, rabbits and a larger population of the European polecat. Noctule bats and common pipistrelle live in the park, the Daubenton's bat was sporadically detected and the Nathusius's pipistrelle is suspected as a guest.[56][57]

Among the breeding birds, the Eurasian hobby, the Eurasian sparrowhawk, the common kingfisher, the European pied flycatcher and the wood warbler are particularly noteworthy. The park is an important stop for migratory birds or as winter habitat. The red-crested pochard, for example, (threatened with extinction in Bavaria) appears during the winter. Nearly every year Bohemian waxwings overwinter in the Nymphenburg Park. In unusually hard winters, bird species from northern and north-eastern Europe migrate to southern Bavaria with many thousands of specimens. Nymphenburg Park is traditionally their most important winter quarter.[58][59]

The very rare hermit beetle lives in and on the park trees. Numerous butterfly species can be found on calcareous grasslands, such as meadow brown, silver-washed fritillary, common brimstone, orange tip and purple emperor. The Kugelweiher pond in the north of the park is home to common toads and frogs, the grass snake and several dragonfly species, including the common winter damselfly.

In contrast to its layout, the palace park is now completely surrounded by urban areas. A biological exchange with populations outside, apart from birds, robust insects and some other highly mobile species, is hardly possible. The Nymphenburg Canal to the east and the line of sight to Blutenburg Castle in the west offer only narrow connections that are highly disturbed in their ecological function. The Kapuzinerhölzl forest that adjoins the park to the north is isolated with it.

The Nymphenburg Palace Park is a registered landscape conservation area and was also reported to the European Union as a Fauna-Flora-Habitat area for the European Biotope Network. The City of Munich has yet to implement a proposal for the designation as a nature reserve since 1987. There are several natural monuments in the park: two groups of six and nine old yew trees near the Amalienburg, as well as outstanding individual trees. A solitary beech tree immediately to the south and a gnarled and bizarrely grown linden tree on the lake shore north of Badenburg, also a solitary common beech tree at a junction south of the Amalienburg, a weeping beech tree near the swan bridge and an oak in The Village. Human intervention such as care of the lawns, artificial plantings and the removal of dead wood in the context of traffic safety obligations are classified under low intensity. Meadow mowing has been rated as positive for biodiversity.[60][61]

Historical classification

.jpg.webp)

Of the garden creations by Dominique Girard and Joseph Effner, only the water parterre to the east and the Northern Cabinet Garden to the northwest of the main palace are preserved in addition to the canal system and the palace buildings. The splendor of the extensive garden furnishings can still be seen in the two paintings by Bernardo Bellotto.

The gardens of the Nymphenburg Palace experienced their greatest changes with the creation of the landscape park by Ludwig von Sckell. It was a redesign and at the same time a further development. The Garden parterre, committed to the French garden style and the water axis have been left, but were simplified. The forest area, originally segmented by hunting aisles, the bosquetted areas and the embedded, independent, formal Garden parterres of the three Parkschlösschen castles were subjected to a uniform overall planning and transformed into a self-contained English-style landscape park in which a considerable proportion was converted into water areas.

Historical background

The establishment of English gardens by princely houses after the French Revolution and its slipping into a reign of terror has been assessed differently than the creation of park landscapes before 1789 by an aristocratic avant-garde who had invented the new "natural" garden style. These include Stourhead in England (by Henry Hoare the Younger), Ermenonville in France (by René Louis de Girardin), Wörlitz in Anhalt (by Franz von Anhalt-Dessau), Alameda de Osuna (by Maria Josefa Pimentel) in Spain and Arkadia in Poland (by Helene Radziwiłł). What they have in common is a new understanding of the relationship between man and nature and social reform approaches based on the equality of all people, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau had propagated in his writings.[62][63]

The aristocratic utopians, endowed with considerable financial resources, found imitators and the romantic landscape garden eventually became contemporary fashion. The renovation of the existing gardens consumed immense sums of money, which quite likely matched the costs of the creation of actual Baroque gardens.

The exploitation of the new garden concept for the monarchy

At the beginning of the 19th century, the construction of a landscape garden was in no way an expression of a utopia or revolutionary idea. The European monarchies countered the impending loss of power through external modernization. A visible expression of this trend was the adoption of the new, fashionable garden style. The large Englischer Garten on the Isar meadows north of the Residenz was created in Munich. It is a park for the common people and was therefore to be understood as a social signal. However, little changed in the political constitution of the kingdom. The desire of the monarchy for peace was perhaps nowhere as recognizable as in the harmonious design of the new Nymphenburg landscape.

The transformation of the landscape might have succeeded, but society did not. The Nymphenburger Park reveals this in its iconological program: the large number of antique statues of the gods are dedicated to the monarchy and allude to the divine hierarchical order as the basis of all moral values. The furnishings of the parks of Ermenonville, however, were completely different. A copy of the Rousseau island, as built by Franz von Anhalt-Dessau and Helene Radziwiłł, would have been unthinkable for a Bavarian king.

Sckell's landscapes conveyed no political ideas. This was the only way to disconnect from Rousseau's ideas and to link the new garden style to traditional elements, as symbolized by the water axis, the Pagodenburg and the Badenburg. However, this also created the prerequisite for the beauty of the park landscape and its lasting timelessness.

Management and maintenance of the park

The Nymphenburger Park is looked after by the Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen (Bavarian administration of the state palaces, gardens and lakes). The maintenance of the park requires the integration of the preservation of historical garden art monuments, nature protection, recreational use by the visitors and traffic safety obligations. The yardstick for maintenance is the Garden monument preservation objective, which was developed in 1989/1990. It compares the historical documents with the current state and develops cautious measures to bring the park's appearance closer to its origin. These are implemented in small steps in the medium and long term.

From 2006 to 2012 the administration developed together with the Bavarian State Institute for Forests and Forestry a model project "Forest maintenance as garden monument maintenance and biotope maintenance" based on the Nymphenburg Palace Park.[64]

Due to the sensitivity of visitors to tree felling, interventions are carried out step by step and with a long planning horizon of around 30 years. Test were also conducted on how visitors react to information on park maintenance and the justification of interventions.

References

- "Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes". Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- "Germany". EEA. November 12, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "Gebietsbeschreibung zum Landschaftsschutzgebiet Nymphenburg". MuenchenTransparent. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "Verordnung der Landeshauptstadt München über das Landschaftsschutzgebiet "Nymphenburg"". Landeshauptstadt München. July 27, 2005. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Rudolf Seitz, Albert Lang, Astrid Hanak, Rüdiger Urban. "Der Schlosspark Nymphenburg als Teil eines Natura 2000-Gebietes". Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten. Retrieved January 16, 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Schlosspark Nymphenburg". München de. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- "Historische Parks und Gärten sind ein geistiger, kultureller, ökologischer und gesellschaftlicher Besitz von unersetzlichem Wert". Schlosspark-Freunde-Nymphenburg e.V. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Carl August Sckell (1840). Das königliche Lustschloß Nymphenburg und seine Gartenanlagen: mit einem Plane. Jaquet. pp. 39–.

- Rainer Herzog. "Die Behandlung Von Alleen Des 18. Jahrhunderts in Nympenburg..." (PDF). ICOMOS International. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Würmlehrpfad und Münchner Umweltwanderwege". Referat für Gesundheitund Umwelt. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Werner Ebnet (13 June 2016). Sie haben in München gelebt: Biografien aus acht Jahrhunderten. BUCH&media. pp. 523–. ISBN 978-3-86906-911-1.

- "Biography Amedeo di Castellamonte" (PDF). Venaria Palace. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- Gordon Campbell (31 October 2016). Gardens: A Short History. OUP Oxford. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-19-108755-4.

- Girard, Dominique. Oxford Reference. January 2006. ISBN 9780198662556. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- "Joseph Effner". Oxford Index. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- Alan J. Christensen. Dictionary of Landscape Architecture and Construction. Academia. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- Christopher Thacker (1979). The History of Gardens. University of California Press. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-0-520-03736-6.

- "Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell". kulturreise-ideen. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "Skell, Friedrich Ludwig von". Hessisches Landesamt für geschichtliche Landeskunde. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- "Sckell, Friedrich Ludwig von, Beitraege zur bildenden Gartenkunst für angehende Gartenkünstler und Gartenliebhaber". Uni Heidelberg. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Marie Luise Schroeter Gothein (11 September 2014). A History of Garden Art. Cambridge University Press. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-1-108-07615-9.

- "kulturgeschichtspfad Neuhausen-Nymphenburg" (PDF). Landeshauptstadt München. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- Dominik Peters (May 31, 2018). "Die Amazonen-Partys der Nazis". Der Spiegel. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "Equestrianism at the 1972 Summer Games". sports reference. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Pius Bieri. "Schloss Nymphenburg - 1. Die Schlossgebäude". Süddeutscher Barock. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Gordon McLachlan (2004). The Rough Guide to Germany. Rough Guides. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-1-84353-293-4.

- Matthias Staschull. "Fassadenbefunde aus der Zeit Max Emanuels von Bayern - Schloss Nymphenburg und das Neue Schloss Schleißheim". Uni Heidelberg. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Nymphenburg palace, Germany". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Hans Graf. "Der Renaissance Garten". Graf Gartenbau. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- "TECHNIK IM DIENSTE DER GARTENKUNST" (PDF). Schloss Nymphenburg. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- "Fontäne im Schlossrondell". München im Bild. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- John D. Lyons (8 August 2019). The Oxford Handbook of the Baroque. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-0-19-067846-3.

- "Badenburg - First heated indoor pool of modern times". München de. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- "Badenburg". München de. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- "Münchner Straßenverzeichnis Die Badenburg". stadtgeschichte muenchen. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "François de Cuvilliés". Getty. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "Die Pagodenburg Im Schlosspark Nymphenburg Zu München – Darin Amsterdamer Und Rotterdamer Fayencefliesen". Tegels uit Rotterdam. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Schloss und Schlossgarten Nymphenburg - Die Gartengebäude von Kurfürst Max II. Emanuel - Die Pagodenburg" (PDF). Süddeutscher Barock ch. October 7, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Eric Garberson (March 1, 1992). "Review: Die Exotismen des Kurfürsten Max Emanuel in Nymphenburg: Eine kunst- und kulturhistorische Studie zum Phänomen von Chinoiserie und Orientalismus in Bayern und Europa by Ulrika Kiby (english text)". UC Press - Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- "François de Cuvilliés". Getty. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- Joanna Banham (May 1997). Encyclopedia of Interior Design. Routledge. pp. 359–. ISBN 978-1-136-78758-4.

- James Stevens Curl; Susan Wilson (2015). The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5.

- "Cuvilliés, François de, the Elder - Interior view". Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "François Cuvilliés (1695–1768) - Die Amalienburg". Süddeutscher Barock. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Magdalenenklause". München im Bild. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "Baader, Joseph von". Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "Das Eiserne Haus im Nymphenburger Schlosspark" (PDF). Orangeriekultur. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "Franz Ignaz Günther.. Der grosse Bildhauer des bayerischen Rokoko". ZVAB. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Julia Strobl. "JOHANN BAPTIST STRAUB" (PDF). ZVAB. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Ruth Johnen (1938). Roman Anton Boos, kurfürstlicher Hofbildhauer zu München, 1733-1810.

- Joanna Banham (1 May 1997). Encyclopedia of Interior Design. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1724–. ISBN 978-1-136-78757-7.

- "Figur des Pan auf dem Felsen, Skulptur von Peter Simon Lamine". Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- J. Rohr (21 October 2019). Der Straßburger Bildhauer Landolin Ohmacht: Eine kunstgeschichtliche Studie samt einem Beitrag zur Geschichte der Ästhetik um die Wende des 18. Jahrhunderts. De Gruyter. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-3-11-147926-2.

- "Die Münchner Bildhauerschule" (PDF). Uni Heidelberg. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "Die Eichen im Schlosspark Nymphenburg". Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- Monika Hoffmann (June 14, 2015). "Schlosspark Nymphenburg: Einzigartiges Naturparadies mitten in München". Reise-Zikaden. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "Schlossgärten als Horte der Artenvielfalt". Bayerische Akademie für Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- Thomas Grüner. "Die Waldvögel des Nymphenburger Schlossparks". Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "Friedliche Invasion – Nordische Seidenschwänze besuchen München in großer Zahl". Landesbund für Vogelschutz in Bayern. January 19, 2005. Archived from the original on 2005-02-09. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "Europäisches Netz Natura 2000 Fauna-Flora-Habitate" (PDF). Uni Trier. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- Cecil C. Konijnendijk; Kjell Nilsson; Thomas B. Randrup (20 May 2005). Urban Forests and Trees: A Reference Book - Central Europe - Munich. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-3-540-25126-2.

- "Garden Kingdom of Dessau-Wörlitz - Outstanding Universal Value". United Nations. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- "Le parc Jean-Jacques Rousseau". Parc à fabriques. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- "LWF-Wissen 68 Schlosspark Nymphenburg". Bayerische Landesanstalt für Wald und Forstwirtschaft. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

Bibliography

- Förg, Klaus G. (2012). Schloss Nymphenburg (in English and German). Rosenheim, Germany: Rosenheimer Verlagshaus. ISBN 978-3-475-53270-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fuchsberger, Doris (2017). Nacht der Amazonen. Eine Münchner Festreihe zwischen NS-Propaganda und Tourismusattraktion [Night of the Amazons. A series of Munich festivals between Nazi-propaganda and touristic attraction] (in German). München, Germany: Allitera. ISBN 978-3-86906-855-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gardens of Nymphenburg Palace. |

.JPG.webp)