Pacemaker syndrome

Pacemaker syndrome is a condition that represents the clinical consequences of suboptimal atrioventricular (AV) synchrony or AV dyssynchrony, regardless of the pacing mode, after pacemaker implantation.[1][2] It is an iatrogenic disease—an adverse effect resulting from medical treatment—that is often underdiagnosed.[1][3] In general, the symptoms of the syndrome are a combination of decreased cardiac output, loss of atrial contribution to ventricular filling, loss of total peripheral resistance response, and nonphysiologic pressure waves.[2][4][5]

| Pacemaker syndrome | |

|---|---|

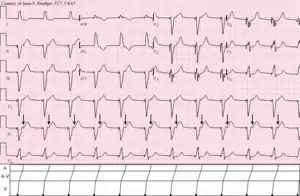

| |

| Ventricular pacemaker with 1:1 retrograde ventriculoatrial (V-A) conduction to the atria (arrows). | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

Individuals with a low heart rate prior to pacemaker implantation are more at risk of developing pacemaker syndrome. Normally the first chamber of the heart (atrium) contracts as the second chamber (ventricle) is relaxed, allowing the ventricle to fill before it contracts and pumps blood out of the heart. When the timing between the two chambers goes out of synchronization, less blood is delivered on each beat. Patients who develop pacemaker syndrome may require adjustment of the pacemaker, or fitting of another lead to better coordinate the timing of atrial and ventricular contraction.

Signs and symptoms

No specific set of criteria has been developed for diagnosis of pacemaker syndrome. Most of the signs and symptoms of pacemaker syndrome are nonspecific, and many are prevalent in the elderly population at baseline. In the lab, pacemaker interrogation plays a crucial role in determining if the pacemaker mode had any contribution to symptoms.[5][6][7]

Symptoms commonly documented in patients history, classified according to cause:[2][5][6][8][9]

- Neurological - Dizziness, near syncope, and confusion.

- Heart failure - Dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and edema.

- Hypotension - Seizure, mental status change, diaphoresis, and signs of orthostatic hypotension and shock.

- Low cardiac output - Fatigue, weakness, dyspnea on exertion, lethargy, and lightheadedness.

- Hemodynamic - Pulsation in the neck and abdomen, choking sensation, jaw pain, right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain, chest colds, and headache.

- Heart rate related - Palpitations associated with arrhythmias

In particular, the examiner should look for the following in the physical examination, as these are frequent findings at the time of admission:[2][5][6][8]

- Vital signs may reveal hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, or low oxygen saturation.

- Pulse amplitude may vary, and blood pressure may fluctuate.

- Look for neck vein distension and cannon waves in the neck veins.

- Lungs may exhibit crackles.

- Cardiac examination may reveal regurgitant murmurs and variability of heart sounds.

- Liver may be pulsatile, and the RUQ may be tender to palpation. Ascites may be present in severe cases.

- The lower extremities may be edematous.

- Neurologic examination may reveal confusion, dizziness, or altered mental status.

Complications

Studies have shown that patients with Pacemaker syndrome and/or with sick sinus syndrome are at higher risk of developing fatal complications that calls for the patients to be carefully monitored in the ICU. Complications include atrial fibrillation, thrombo-embolic events, and heart failure.[7]

Causes

The cause is poorly understood. However several risk factors are associated with pacemaker syndrome.[5][10]

Risk factors

- In the preimplantation period, two variables are predicted to predispose to the syndrome. First is low sinus rate, and second is a higher programmed lower rate limit. In postimplantation, an increased percentage of ventricular paced beats is the only variable that significantly predicts development of pacemaker syndrome.[10]

- Patients with intact VA conduction are at greater risk for developing pacemaker syndrome. Around 90% of patients with preserved AV conduction have intact VA conduction, and about 30-40% of patients with complete AV block have preserved VA conduction. Intact VA conduction may not be apparent at the time of pacemaker implantation or even may develop at any time after implantation.[2][5][10][11]

- Patients with noncompliant ventricles and diastolic dysfunction are particularly sensitive to loss of atrial contribution to ventricular filling and have a greater chance of developing the syndrome. This includes patients with cardiomyopathy (hypertensive, hypertrophic, restrictive) and elderly individuals.[5][7][10][12]

- Other factors correlated with development of pacemaker syndrome include decreased stroke volume, decreased cardiac output, and decreased left atrial total emptying fraction associated with ventricular pacing.[5][10]

Pathophysiology

The loss of physiologic timing of atrial and ventricular contractions, or sometimes called AV dyssynchrony, leads to different mechanisms of symptoms production. This altered ventricular contraction will decrease cardiac output, and in turn will lead to systemic hypotensive reflex response with varying symptoms.[1][2][4][5]

Loss of atrial contraction

Inappropriate pacing in patients with decreased ventricular compliance, which may be caused by diseases such as hypertensive cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and aging, can result in loss of atrial contraction and significantly reduces cardiac output. Because in such cases the atrias are required to provide 50% of cardiac output, which normally provides only 15% - 25% of cardiac output.[8][12]

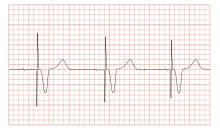

Cannon A waves

Atrial contraction against a closed tricuspid valve can cause pulsation in the neck and abdomen, headache, cough, and jaw pain.[8][10]

Increased atrial pressure

Ventricular pacing is associated with elevated right and left atrial pressures, as well as elevated pulmonary venous and pulmonary arterial pressures, which can lead to symptomatic pulmonary and hepatic congestion.[5]

Increased production of natriuretic peptides

Patients with pacemaker syndrome exhibit increased plasma levels of ANP. That's due to increase in left atrial pressure and left ventricular filling pressure, which is due to decreased cardiac output caused by dyssynchrony in atrial and ventricular contraction. ANP and BNP are potent arterial and venous vasodilators that can override carotid and aortic baroreceptor reflexes attempting to compensate for decreased blood pressure. Usually patients with cannon a waves have higher plasma levels of ANP than those without cannon a waves.[1][13][14]

VA conduction

A major cause of AV dyssynchrony is VA conduction. VA conduction, sometimes referred to as retrograde conduction, leads to delayed, nonphysiologic timing of atrial contraction in relation to ventricular contraction. Nevertheless, many conditions other than VA conduction promote AV dyssynchrony.[1][2][4][8][10]

This will further decrease blood pressure, and secondary increase in ANP and BNP.[13][14]

Prevention

At the time of pacemaker implantation, AV synchrony should be optimized to prevent the occurrence of pacemaker syndrome. Where patients with optimized AV synchrony have shown great results of implantation and very low incidence of pacemaker syndrome than those with suboptimal AV synchronization.[1][4][5]

Treatment

Diet

Diet alone cannot treat pacemaker syndrome, but an appropriate diet to the patient, in addition to the other treatment regimens mentioned, can improve the patient's symptoms. Several cases mentioned below:

- For patients with heart failure, low-salt diet is indicated.[15]

- For patients with autonomic insufficiency, a high-salt diet may be appropriate.[15]

- For patients with dehydration, oral fluid rehydration is needed.[15]

Medication

No specific drugs are used to treat pacemaker syndrome directly because treatment consists of upgrading or reprogramming the pacemaker.[15]

Medical care

- For some patients who are ventricularly paced, usually the addition of an atrial lead and optimizing the AV synchrony usually resolves symptoms.[1][4][8][10]

- In patients with other pacing modes, other than ventricular pacing, symptoms usually resolve after adjusting and reprogramming of pacemaker parameters, such as tuning the AV delay, changing the postventricular atrial refractory period, the sensing level, and pacing threshold voltage. The optimal values of these parameters for each individual differ. So, achieving the optimal values is by experimenting with successive reprogramming and measurement of relevant parameters, such as blood pressure, cardiac output, and total peripheral resistance, as well as observations of symptomatology.[1][4][8][10]

- In rare instances, using hysteresis to help maintain AV synchrony can help alleviate symptoms in ventricularly inhibited paced (VVI) patients providing they have intact sinus node function. Hysteresis reduces the amount of time spent in pacing mode, which can relieve symptoms, particularly when the pacing mode is generating AV dyssynchrony.[4][10]

- If symptoms persist after all these treatment modalities, replacing the pacemaker itself is sometimes beneficial and can alleviate symptoms.[1][4][8]

- Medical care includes supportive treatment, in case any of the following complications happen, medical team should be ready. Possible complications include heart failure, hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, and oxygenation deficit.[1][6][8]

Surgical care

Sometimes surgical intervention is needed. After consulting an electrophysiologist, possibly an additional pacemaker lead placement is needed, which eventually relieve some of the symptoms.[1][4]

Epidemiology

The reported incidence of pacemaker syndrome has ranged from 2%[16] to 83%.[11] The wide range of reported incidence is likely attributable to two factors which are the criteria used to define pacemaker syndrome and the therapy used to resolve that diagnosis.[17]

History

Pacemaker syndrome was first described in 1969 by Mitsui et al. as a collection of symptoms associated with right ventricular pacing.[17][18][19] The name pacemaker syndrome was first coined by Erbel in 1979.[18][20] Since its first discovery, there have been many definitions of pacemaker syndrome, and the understanding of the cause of pacemaker syndrome is still under investigation. In a general sense, pacemaker syndrome can be defined as the symptoms associated with right ventricular pacing relieved with the return of A-V and V-V synchrony.[17]

References

- Ellenbogen KA, Gilligan DM, Wood MA, Morillo C, Barold SS (May 1997). "The pacemaker syndrome -- a matter of definition". Am. J. Cardiol. 79 (9): 1226–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00085-4. PMID 9164889.

- Chalvidan T, Deharo JC, Djiane P (July 2000). "[Pacemaker syndromes]". Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) (in French). 49 (4): 224–9. PMID 12555483.

- Baumgartner, William A.; Yuh, David D.; Luca A. Vricella (2007). The Johns Hopkins manual of cardiothoracic surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. ISBN 978-0-07-141652-8.

- Frielingsdorf J, Gerber AE, Hess OM (October 1994). "Importance of maintained atrio-ventricular synchrony in patients with pacemakers". Eur. Heart J. 15 (10): 1431–40. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060408. PMID 7821326.

- Furman S (January 1994). "Pacemaker syndrome". Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 17 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.1994.tb01342.x. PMID 7511223.

- Nishimura RA, Gersh BJ, Vlietstra RE, Osborn MJ, Ilstrup DM, Holmes DR (November 1982). "Hemodynamic and symptomatic consequences of ventricular pacing". Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 5 (6): 903–10. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.1982.tb00029.x. PMID 6184693.

- Santini M, Alexidou G, Ansalone G, Cacciatore G, Cini R, Turitto G (March 1990). "Relation of prognosis in sick sinus syndrome to age, conduction defects and modes of permanent cardiac pacing". Am. J. Cardiol. 65 (11): 729–35. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(90)91379-K. PMID 2316455.

- Petersen HH, Videbaek J (September 1992). "[The pacemaker syndrome]". Ugeskrift for Læger (in Danish). 154 (38): 2547–51. PMID 1413181.

- Alicandri C, Fouad FM, Tarazi RC, Castle L, Morant V (July 1978). "Three cases of hypotension and syncope with ventricular pacing: possible role of atrial reflexes". Am. J. Cardiol. 42 (1): 137–42. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(78)90998-0. PMID 677029.

- Schüller H, Brandt J (April 1991). "The pacemaker syndrome: old and new causes". Clin Cardiol. 14 (4): 336–40. doi:10.1002/clc.4960140410. PMID 2032410.

- Heldman D, Mulvihill D, Nguyen H, et al. (December 1990). "True incidence of pacemaker syndrome". Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 13 (12 Pt 2): 1742–50. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.1990.tb06883.x. PMID 1704534.

- Gross JN, Keltz TN, Cooper JA, Breitbart S, Furman S (December 1992). "Profound "pacemaker syndrome" in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy". Am. J. Cardiol. 70 (18): 1507–11. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(92)90313-N. PMID 1442632.

- Theodorakis GN, Panou F, Markianos M, Fragakis N, Livanis EG, Kremastinos DT (February 1997). "Left atrial function and atrial natriuretic factor/cyclic guanosine monophosphate changes in DDD and VVI pacing modes". Am. J. Cardiol. 79 (3): 366–70. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(97)89285-5. PMID 9036762.

- Theodorakis GN, Kremastinos DT, Markianos M, Livanis E, Karavolias G, Toutouzas PK (November 1992). "Total sympathetic activity and atrial natriuretic factor levels in VVI and DDD pacing with different atrioventricular delays during daily activity and exercise". Eur. Heart J. 13 (11): 1477–81. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060089. PMID 1334465.

- "Pacemaker Syndrome: Treatment & Medication - eMedicine Cardiology". 2018-04-22. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Andersen HR, Thuesen L, Bagger JP, Vesterlund T, Thomsen PE (December 1994). "Prospective randomised trial of atrial versus ventricular pacing in sick-sinus syndrome". Lancet. 344 (8936): 1523–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90347-6. PMID 7983951.

- Farmer DM, Estes NA, Link MS (2004). "New concepts in pacemaker syndrome". Indian Pacing and Electrophysiology Journal. 4 (4): 195–200. PMC 1502063. PMID 16943933. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- Travill CM, Sutton R (August 1992). "Pacemaker syndrome: an iatrogenic condition". British Heart Journal. 68 (2): 163–6. doi:10.1136/hrt.68.8.163. PMC 1025005. PMID 1389730. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- Mitsui T, Hori M, Suma K, et al. The "pacemaking syndrome." In: Jacobs JE, ed. Proceedings of the 8th Annual International Conference on Medical and Biological Engineering. Chicago, IL: Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation;. 1969;29-3.

- 2 Erbel R. Pacemaker syndrome. AmJ Cardiol 1979;44:771-2.